World Food Programme

| |

| |

The World Food Programme logo and WFP headquarters in Rome | |

| Abbreviation | WFP |

|---|---|

| Formation | 19 December 1961 |

| Type | Intergovernmental organization, Regulatory body, Advisory board |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Rome, Italy |

Head | David Beasley |

Parent organization | United Nations General Assembly |

Staff (2020) | 19,660 |

| Award(s) | Nobel Peace Prize 2020 |

| Website | wfp.org |

The World Food Programme[a] (WFP) is the food-assistance branch of the United Nations. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization,[1] the largest one focused on hunger and food security,[2] and the largest provider of school meals. Founded in 1961, it is headquartered in Rome and has offices in 80 countries.[3] As of 2019, it served 97 million people in 88 countries, the largest since 2012,[4] with two-thirds of its activities conducted in conflict zones.[5]

In addition to emergency food relief, WFP offers technical assistance and development aid, such as building capacity for emergency preparedness and response, managing supply chains and logistics, promoting social safety programs, and strengthening resilience against climate change.[6] The agency is also a major provider of direct cash assistance and medical supplies, and provides passenger services for humanitarian workers.[1][7]

WFP is an executive member of the United Nations Development Group,[8] a consortium of UN entities that aims to fulfil the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), with a priority on achieving SDG 2 for "zero hunger" by 2030.[9]

The World Food Programme was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its efforts to provide food assistance in areas of conflict, and to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict.[10]

History[]

WFP was established in 1961[11] after the 1960 Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Conference, when George McGovern, director of the US Food for Peace Programmes, proposed establishing a multilateral food aid programme. WFP launched its first programmes in 1963 by the FAO and the United Nations General Assembly on a three-year experimental basis, supporting the Nubian population at Wadi Halfa in Sudan. In 1965, the programme was extended to a continuing basis.[12]

Background[]

WFP works across a broad spectrum of Sustainable Development Goals,[9] owing to the fact that food shortages, hunger and malnutrition cause poor health, which subsequently impacts other areas of sustainable development, such as education, employment and poverty (Sustainable Development Goals Four, Eight and One respectively).[9]

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and lockdown has placed significant pressure on agricultural production, disrupted global value and supply chain. Subsequently, this raises issues of malnutrition and inadequate food supply to households with the poorest of them all gravely affected.[13] This is expected to cause "132 million more people to suffer from undernourishment in 2020".[14]

Funding[]

WFP operations are funded by voluntary donations principally from governments of the world, and also from corporations and private donors.[15] In 2019, funding was a record US$8 billion, of which the largest donors were the United States ($3.4 billion) and Germany ($886.6 million). Contributions were insufficient to cover identified needs of food-insecure populations, with a funding gap of US$4.1 billion.[16]

Organization[]

Governance, leadership and staff[]

WFP is governed by an executive board which consists of representatives from 36 member states, and provides intergovernmental support, direction and supervision of WFP's activities. The European Union is a permanent observer in WFP and, as a major donor, participates in the work of its executive board.[17] WFP is headed by an executive director, who is appointed jointly by the UN Secretary-General and the director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The executive director is appointed for fixed five-year terms and is responsible for the administration of the organization as well as the implementation of its programmes, projects and other activities.[18] David Beasley, previously Governor of the U.S. state of South Carolina, was appointed to the role in March 2017. He heads the WFP secretariat, which is headquartered in Rome.

In October 2020, WFP had 19,660 staff.

List of executive directors[]

Since 1992, all executive directors have been American. The following is a chronological list of those who have served as executive director of the World Food Programme:[19]

- Addeke Hendrik Boerma (

Netherlands) (May 1962 – December 1967)

Netherlands) (May 1962 – December 1967) - (

India) (January 1968 – August 1968) (acting)

India) (January 1968 – August 1968) (acting) - (

El Salvador) (July 1968 – May 1976)

El Salvador) (July 1968 – May 1976) - (

United States) (May 1976 – June 1977 acting; July 1977 – September 1977)

United States) (May 1976 – June 1977 acting; July 1977 – September 1977) - (

Canada) (October 1977 – April 1981)

Canada) (October 1977 – April 1981) - (

Brazil) (May 1981 – February 1982) (acting)

Brazil) (May 1981 – February 1982) (acting) - (

Uruguay) (February 1982 – April 1982) (acting)

Uruguay) (February 1982 – April 1982) (acting) - James Ingram (

Australia) (April 1982 – April 1992)

Australia) (April 1982 – April 1992) - Catherine Bertini (

United States) (April 1992 – April 2002)

United States) (April 1992 – April 2002) - (

United States) (April 2002 – April 2007)

United States) (April 2002 – April 2007) - Josette Sheeran (

United States) (April 2007 – April 2012)

United States) (April 2007 – April 2012) - Ertharin Cousin (

United States) (April 2012 – April 2017)

United States) (April 2012 – April 2017) - David Beasley (

United States) (April 2017 – present)

United States) (April 2017 – present)

Activities[]

Emergencies[]

About two-thirds of WFP's life-saving food assistance goes to people facing severe food crises, most of them caused by conflict.[20] By the end of 2020 WFP was tackling emergencies and crises across 20 countries.[21] Its response typically includes a combination of food, cash, nutrition supplements and school feeding. WFP estimates that nearly 272 million people in countries where it operates are acutely food insecure, or at risk of becoming so, due to the aggravating effects of COVID-19. WFP extended its reach to assist nearly 97 million people across 73 countries with critical food and nutrition assistance. A total US$1.7 billion in cash assistance was distributed to vulnerable people in 67 countries from January to October 2020. WFP also expanded its monitoring from 15 to 39 countries, to track real-time, evolving needs.[22]

WFP's largest and most complex emergency response is in Yemen, amidst ongoing conflict, a ravaged economy and a decimated health system unable to cope with COVID-19, factors that are combining to cause one of the worst hunger crises in the world and which threaten famine.[23] In Syria, WFP provides food assistance to more than 4.5 million people amidst a civil war that has displaced over 6.5 million people.[24]

WFP is also a first responder to sudden-onset emergencies. When floods struck Sudan in July 2020, it provided emergency food assistance to nearly 160,000 people.[25] WFP provided food as well as vouchers for people to buy vital supplies, while also planning recovery, reconstruction and resilience-building activities, after Cyclone Idai struck Mozambique and floods washed an estimated 400,000 hectares of crops on early 2019.[26]

WFP's emergency is also pre-emptive, in offsetting the potential impact of disasters. In the Sahel region of Africa, amidst economic challenges, climate change and armed militancy, WFP's activities included working with communities and partners to harvest water for irrigation and restore degraded land, and supporting livelihoods through skills training.[27] It uses early-warning systems to help communities prepare for disasters. In Bangladesh, weather forecasting led to distributions of cash to vulnerable farmers to pay for measures such as reinforcing their homes or stockpiling food ahead of heavy flooding.[28]

WFP coordinates responses to large-scale emergencies on behalf of the wider humanitarian community, as lead agency of the Logistics Cluster and the Emergency Telecommunications Cluster. It also co-leads the Food Security Cluster. The WFP-managed United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) serves over 300 destinations globally. WFP also manages the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depot (UNHRD), a global network of hubs that procures, stores and transports emergency supplies for the organization and the wider humanitarian community. WFP logistical support, including its air service and hubs, has enabled staff and supplies from WFP and partner organizations to reach areas where commercial flights have not been available, during the COVID-19 pandemic.[29]

Emergency Response procedures

WFP has a system of classifications known as the Emergency Response Procedures designed for situations that require an immediate response. This response is activated under the following criteria:

- When human suffering exists and domestic governments cannot respond adequately

- The United Nations reputation is under scrutiny

- When there is an obvious need for aid from WFP

The Emergency Response Classifications are divided as follows, with emergency intensity increasing with each level:[30]

- Level 1 – Response is activated. Resources are allocated to prepare for WFP's local office to respond

- Level 2 – A country's resources require regional assistance with an emergency across one or multiple countries/territories

- Level 3 (L3) – The emergency overpowers WFP's local offices and requires a global response from the entire WFP organisation

Climate change[]

WFP works with governments and humanitarian partners in responding to increasing number of climate-related disasters. It also takes pre-emptive action to reduce the number of people needing humanitarian assistance. WFP used Forecast-based Financing to provide cash to vulnerable families, allowing them to buy food, reinforce their homes and take other steps to build resilience ahead of torrential rains in Bangladesh in July 2019.[31] WFP's response to Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas in September 2019 was assisted by a regional office in Barbados, which had been set up the previous year to enable better disaster preparedness and response. In advance of Hurricane Dorian, WFP deployed technical experts in food security, logistics and emergency telecommunication, to support a rapid needs assessment. Assessment teams also conducted an initial aerial reconnaissance mission, with the aim of putting teams on the ground as soon as possible.[32]

Nutrition[]

WFP has broadened its focus in recent years from emergency interventions to addressing all forms of malnutrition including vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and overweight and obesity. WFP addresses malnutrition from the earliest stages through programmes targeting the first 1,000 days from conception to a child's second birthday.[33] It provides access to healthy diets, targeting young children, pregnant and breastfeeding women and people living with HIV and TB.[34][35] WFP works with governments, other UN agencies, NGOs and the private sector, supporting nutrition interventions, policies and programmes that include nutritious school meals and food fortification.[36]

School feeding[]

School meals encourage parents in vulnerable families to send their children to school, rather than work. They have proved highly beneficial in areas including education and gender equality, health and nutrition, social protection, local economies and agriculture.[37] WFP works with partners to ensure school feeding is part of integrated school health and nutrition programmes, which include services such as malaria control, menstrual hygiene and guidance on sanitation and hygiene.[38]

Smallholder farmers[]

Smallholder farmers produce most of the world's food and are critical in achieving a zero-hunger world. WFP's support to farmers spans a range of activities to help build sustainable food systems, from business-skills training to opening up roads to markets.[39] WFP is among a global consortium that forms the Farm to Market Alliance, which helps smallholder farmers receive information, investment and support, so they can produce and sell marketable surplus and increase their income.[40] WFP connects smallholder farmers to markets in more than 40 countries. It procured 96,600 mt from smallholder farmers for a total of US$37.2 million in 2019, helping improve the smallholders’ livelihoods.[41]

In 2008, WFP coordinated the five-year Purchase for Progress (P4P) pilot project. P4P assists smallholding farmers by offering them opportunities to access agricultural markets and to become competitive players in the marketplace. The project spanned across 20 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and trained 800,000 farmers in improved agricultural production, post-harvest handling, quality assurance, group marketing, agricultural finance, and contracting with WFP. The project resulted in 366,000 metric tons of food produced and generated more than US$148 million in income for its smallholder farmers.[42]

Asset creation[]

WFP's Food Assistance for Assets (FFA) programme is one of WFP's key initiatives aimed at i) addressing the most vulnerable people's immediate food needs with cash, voucher or food transfers when they need them and ii) improving people and communities’ long-term food security and resilience.

Through FFA people receive cash or food-based transfers to address their immediate food needs, while they build or boost assets, such as repairing irrigation systems, bridges, land and water management activities, that will improve their livelihoods by creating healthier natural environments, reducing risks and impact of climate shocks, increasing food productivity, and strengthening resilience to natural disasters over time.

FFA reflects WFP's drive towards food assistance and development rather than food aid and dependency. It does this by placing a focus on the assets and their impact on people and communities rather than on the work to realize them, representing a shift away from the previous approaches such as Food or Cash for Work programmes and large public works programmes.[43]

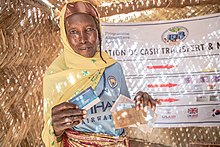

Cash assistance[]

WFP is the largest cash provider in the humanitarian community. The aim is to provide better value for people and donors, allowing for increased food choices and diet diversity for beneficiaries, while boosting local smallholder production, retail and the financial sector. WFP and the European Union joined forces with the Government of Turkey and the Turkish Red Crescent to launch the Emergency Social Safety Net in 2016, one of the largest humanitarian cash programmes ever mounted by the United Nations and the largest humanitarian project the EU has ever funded. It provides monthly cash to vulnerable refugees using individual debit cards. A 2019 survey revealed that the project helped prevent 1.7 million refugees from falling deeper into poverty. WFP stepped back in April 2020, with the International Federation of the Red Cross and Crescent Societies taking over its role.[44][45]

Capacity building[]

WFP places a strong emphasis on transferring skills and knowledge to a range of public, private and civil society actors who are pivotal to sustaining national policies and programmes. The goal is to build governments’ and other partners’ capacities to manage disaster risk and improve food security, while also investing in early warning and preparedness systems for climate and other threats. In the most climate disaster-prone provinces of the Philippines for example, WFP is providing emergency response training and equipment to local government units, and helping set up Automated Weather Stations.[46]

Digital innovation[]

WFP's digital transformation centres on deploying the latest technologies and data to help achieve zero hunger. WFP's Munich-based Innovation Accelerator has sourced and supported more than 60 projects spanning 45 countries.[47] In 2017, WFP launched the Building Blocks programme. It aims to distribute money-for-food assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan. The project uses blockchain technology to digitize identities and allow refugees to receive food with eye scanning.[23] WFP's low-tech hydroponics kits allow refugees to grow barley that feed livestock in the Sahara desert.[48]

Partnerships[]

WFP works with thousands of partners, including governments, private sector, UN agencies, international finance groups, academia, NGOs and other civil society groups. The more than 1,000 NGOs it collaborates with around the world forms its biggest group of partners.[49] WFP places strong emphasis on its partnership with the other two Rome-Based agencies – the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. The agencies reaffirmed their joint efforts to end global hunger, particularly amid the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, during a joint meeting of their governing bodies in October 2020.[50] In the United States, Washington, D.C.-based 501(c)(3) organization World Food Program USA supports the WFP. The American organisation frequently donates to the WFP, though the two are separate entities for taxation purposes.[51]

Reviews[]

Recognition and awards[]

WFP won the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize for its "efforts for combating hunger", its "contribution to creating peace in conflicted-affected areas," and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict.[52][53] Receiving the award, Executive David Beasley called for billionaires to “step up” and help source the US$5 billion WFP needs to save 30 million people from famine.[54]

Challenges[]

In 2018 the Center for Global Development ranked WFP last in a study of 40 aid programmes, based on indicators grouped into four themes: maximising efficiency, fostering institutions, reducing burdens, and transparency and learning. These indicators relate to aid effectiveness principles developed at the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008), and the Busan Partnership Agreement (2011).[55]

There is wide general debate on the net effectiveness of aid, including unintended consequences such as increasing the duration of conflicts, and increasing corruption. WFP faces difficult decisions on working with some regimes.[56]

Some surveys have shown internal culture problems at WFP, including harassment.[57][58]

See also[]

- Asia Emergency Response Facility, a WFP special operation to establish an emergency response facility in Asia

- Fight Hunger, a WFP initiative to end child hunger by 2015

- Food Force, an educational game published by WFP

- World Food Council, a defunct UN agency absorbed by FAO and WFP

Notes[]

- ^ French: Programme alimentaire mondial; Italian: Programma alimentare mondiale; Spanish: Programa Mundial de Alimentos; Arabic: برنامج الأغذية العالمي, romanized: barnamaj al'aghdhiat alealami; Russian: Всемирная продовольственная программа, romanized: Vsemirnaya prodovol'stvennaya programma; Chinese: 世界粮食计划署; pinyin: Shìjiè Liángshí Jìhuà Shǔ

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WFP: $6.8bn needed in six months to avert famine amid COVID-19". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ WFP. "Mission Statement". WFP. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Overview Archived 16 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. WFP.org. Retrieved 19 November 2018

- ^ "Overview". www.wfp.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Picheta, Rob. "World Food Programme was created as an experiment. It sent food to 97 million last year". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Country Capacity Strengthening | World Food Programme". www.wfp.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Afp (9 October 2020). "World Food Programme | Five things to know about 2020 Nobel Peace Prize winner". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ The organization has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize 2020 for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict Executive Committee Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Undg.org. Retrieved on 15 January 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Zero Hunger". World Food Program. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Specia, Megan; Stevis-Gridneff, Matina (9 October 2020). "World Food Program Awarded Nobel Peace Prize for Work During Pandemic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ "UN Food Programme – History". World Food Program. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Elga Zalite. "World Food Programme – An Overview" (PDF). Stanford University Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Gulseven, Osman; Al Harmoodi, Fatima; Al Falasi, Majid; ALshomali, Ibrahim (2020). "How the COVID-19 Pandemic Will Affect the UN Sustainable Development Goals?". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3592933. ISSN 1556-5068. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "UN/DESA Policy Brief #81: Impact of COVID-19 on SDG progress: a statistical perspective | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Funding and donors". www.wfp.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "WFP Annual Performance Report for 2019". WFP. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "European Union". Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Governance and leadership". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Previous WFP Executive Directors". World Food Programme. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Hunger, Conflict, and Improving the Prospects for Peace". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Khorsandi, Peyvand (9 October 2020). "12 things you didn't know about the World Food Programme". World Food Programme. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP Global Update on COVID-19: November 2020". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Hincks, Joseph (9 December 2020). "'2021 Is Going To Be Catastrophic.' For the Director of the World Food Programme, Winning the Nobel Peace Prize Is No Cause for Celebration". Time. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Pangman, Taylor (26 October 2020). "Humanitarian Organizations Addressing Hunger in Syria". Borgen Magazine. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP expands assistance to families struggling in flood-devastated regions of Sudan". World Food Programme. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "All you need to know about 2020 Nobel Peace Prize winner Word Food Programme". Times of India. 9 October 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "World Food Programme Reinforces the Resilience of the Population in the Sahel". United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP provides assistance to communities at risk of monsoon flooding". World Food Programme. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Chan, Selina (31 March 2020). "The chain that coronavirus cannot break". World Food Programme. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP Emergency Response Classifications" (PDF). World Food Programme. 8 May 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Rowling, Megan (23 October 2020). "Analysis: As disaster train gathers speed, efforts gear up to clear the track". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP lends expertise before and after Hurricane Dorian". ReliefWeb. 8 September 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Maro, Alice (18 July 2019). "Saving lives in the first 1,000 days". World Food Programme. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Nutrition". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP launches seasonal support for 1 million people in Mali". infomigrants.net. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Ahmad, Reaz (10 August 2020). "Bangladesh introduces micronutrient-enriched fortified rice first time in OMS". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "The impact of school feeding programmes". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Joint Advocacy Brief - Stepping up effective school health and nutrition". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Changing lives for smallholder farmers". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Farm to Market Alliance secures additional public funding from Norway". World Food Programme. 28 December 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Annual performance report for 2019". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Purchase for Progress: Reflections on the pilot, February 2015 Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. WFP.org. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "How Asset Creation & Livelihood Diversification Brings Resilience to Kenya's Arid Counties". Agrilinks. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Summers, Hannah (26 March 2018). "'Why we're paying the rent for a million Syrian refugees'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Cash assistance from WFP and the European Union helps keep Syrian refugees in Turkey out of poverty". World Food Programme. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "World Food Programme: Emergency response and preparedness". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "WFP Innovation Accelerator". solutions-summit.org. Solutions Summit. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Vetter, David (22 September 2020). "Iris Scans, Hydroponics And Blockchain: How Innovation Is Helping Fight Global Hunger". Forbes. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Partner with us". wfp.org. World Food Programme. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "FAO, IFAD and WFP pledge to strengthen collaboration against hunger". ReliefWeb. 12 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Funke, Daniel; Dc 20036. "Fact-checking claims about charities linked to Hunter Biden and the Trump children". PolitiFact. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Peace Prize, Nobel. "The Nobel Peace Prize 2020". The Nobel Prize. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "UN's World Food Programme wins Nobel peace prize". The Guardian. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ McNamara, Audrey (10 October 2020). "U.N. World Food Program director calls on billionaires to "step up" after Nobel Peace Prize win". CBS News. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "How Do You Measure Aid Quality and Who Ranks Highest?". Center for Global Development. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ 'Yemen: World Food Programme to cut aid by half in Houthi-controlled areas', BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-52239645

- ^ Lynch, Colum. "Popular U.N. Food Agency Roiled by Internal Problems, Survey Finds". Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Senior UN figures under investigation over alleged sexual harassment". The Guardian. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World Food Programme. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: World Food Programme |

- Official website

- World Food Programme on Nobelprize.org

- World Food Programme

- Executive Directors of the World Food Programme

- Agriculture in society

- Government agencies established in 1961

- Government agencies established in 1963

- Hunger relief organizations

- International medical and health organizations

- Italy and the United Nations

- Malnutrition organizations

- Organisations based in Rome

- Organizations awarded Nobel Peace Prizes

- United Nations Development Group