1968 United States presidential election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 60.9%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

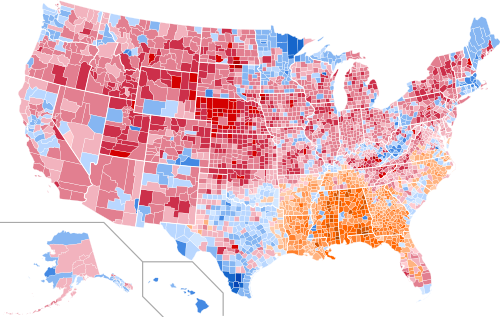

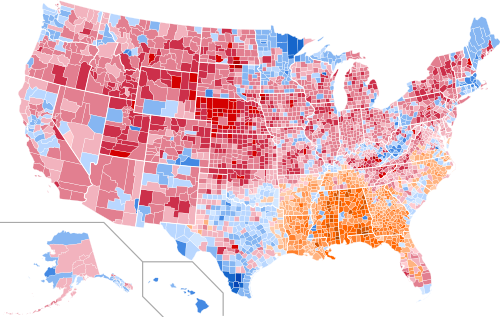

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Nixon/Agnew, blue denotes those won by Humphrey/Muskie, and orange denotes those won by Wallace/LeMay, including a North Carolina faithless elector. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1968 United States presidential election was the 46th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 5, 1968. The Republican nominee, former vice president Richard Nixon, defeated the Democratic nominee, incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey, and the American Independent Party nominee, Alabama Governor George Wallace.

Incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson had been the early front-runner for the Democratic Party's nomination, but he withdrew from the race after only narrowly winning the New Hampshire primary. Eugene McCarthy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Humphrey emerged as the three major candidates in the Democratic primaries until Kennedy was assassinated. Humphrey won the nomination, sparking numerous anti-war protests. Nixon entered the Republican primaries as the front-runner, defeating liberal New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, and conservative Governor of California Ronald Reagan, and other candidates to win his party's nomination. Alabama's Democratic governor, George Wallace ran on the American Independent Party ticket, campaigning in favor of racial segregation.

The election year was tumultuous; it was marked by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in early April and subsequent riots across the nation, the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in early June, and widespread opposition to the Vietnam War across university campuses. Vice President Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic nomination, promising to continue Johnson's war on poverty and to support the civil rights movement. Such ideas hurt Humphrey's image in the South, leading to prominent conservative Democratic governor of Alabama, George Wallace to mount a third party challenge against his own party to defend racial segregation. Wallace led a far-right American Independent Party attracting socially conservative voters throughout the South, and encroaching further support from white-working class voters in the Industrial Midwest who were attracted to Wallace's economic populism. In doing so, Wallace split the Democratic vote against Humphrey, allowing Republican nominee Richard Nixon to win the presidency despite carrying only 43% of the popular vote. Nixon previously served as Vice President under Dwight Eisenhower for eight years, and chose to take advantage of Democratic infighting by running a centrist platform attracting moderate voters as part of his "silent majority" who were alienated by the liberal agenda that was advocated by Hubert Humphrey, and the ultra-conservative viewpoints shared by George Wallace on social issues regarding race and civil rights. Nixon sought to restore law and order to the nation's cities and provide new leadership in the Vietnam War. During most of the campaign, Humphrey trailed significantly in polls taken by late August but narrowed Nixon's lead after Wallace's candidacy collapsed and Johnson suspended bombing in the Vietnam War. Despite a last minute effort to win the presidency, Humphrey was unable to surpass Nixon in the final days of the campaign, losing the electoral college significantly as well as the popular vote by a narrow margin.

Richard Nixon was able to win the Electoral College, dominating several regions in the Western United States, Midwest, Upper South, and portions of the Northeast, while winning the popular vote by a relatively small 511,944 votes over Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey. Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey performed relatively well in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, carrying 191 electoral votes. Lastly, Wallace won five states in the Deep South and ran well in some ethnic enclave industrial districts in the North; he is the most recent third party candidate to win one or more states.[2]

This was the first presidential election after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had resulted in growing restoration and enforcement of the franchise for racial minorities, especially in the South, where most had been disenfranchised since the turn of the century. Minorities in other areas also regained their ability to vote.[3]

Richard Nixon's victory is most similar to the 1912 United States Presidential Election where Democratic nominee at the time, Woodrow Wilson won in a reversal situation with a Republican split between President Taft and his archenemy, Theodore Roosevelt. Despite an embarrassing defeat in the presidential level, Democrats were still able to maintain a solid majority in both the Senate, and House of Representatives in simultaneous congressional elections that took place, continuing Democratic dominance in both state and local levels during the Fifth Party System which had begun since Franklin D. Roosevelt's election win in 1932. Richard Nixon also became the first non-incumbent vice president to be elected president, a feat that was not repeated until 2020, when Joe Biden was elected president.[4]

Historical background[]

In the election of 1964, incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson won the largest popular vote landslide in U.S. presidential election history over Republican United States Senator Barry Goldwater. During the presidential term that followed, Johnson was able to achieve many political successes, including passage of his Great Society domestic programs (including "War on Poverty" legislation), landmark civil rights legislation, and the continued exploration of space. Despite these significant achievements, Johnson's popular support would be short-lived. Even as Johnson scored legislative victories, the country endured large-scale race riots in the streets of its larger cities, along with a generational revolt of young people and violent debates over foreign policy. The emergence of the hippie counterculture, the rise of New Left activism, and the emergence of the Black Power movement exacerbated social and cultural clashes between classes, generations, and races. Adding to the national crisis, on April 4, 1968, civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, igniting riots of grief and anger across the country. In Washington, D.C. rioting took place within a few blocks of the White House, and the government stationed soldiers with machine guns on the Capitol steps to protect it.[5][6]

The Vietnam War was the primary reason for the precipitous decline of President Lyndon B. Johnson's popularity. He had greatly escalated U.S. commitment: By late 1967, over 500,000 American soldiers were fighting in Vietnam. Draftees made up 42 percent of the military in Vietnam, but suffered 58% of the casualties, as nearly 1000 Americans a month were killed and many more were injured.[7] But resistance to the war rose as success seemed ever out of reach. The national news media began to focus on the high costs and ambiguous results of escalation, despite Johnson's repeated efforts to downplay the seriousness of the situation.

In early January 1968, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said the war would be winding down, claiming that the North Vietnamese were losing their will to fight. But, shortly thereafter, they launched the Tet Offensive, in which they and Communist Vietcong forces undertook simultaneous attacks on all government strongholds across South Vietnam. Though the uprising ended in a U.S. military victory, the scale of the Tet offensive led many Americans to question whether the war could be "won", or was worth the costs to the US. In addition, voters began to mistrust the government's assessment and reporting of the war effort. The Pentagon called for sending several hundred thousand more soldiers to Vietnam. Johnson's approval ratings fell below 35%. The Secret Service refused to let the president visit American colleges and universities, and prevented him from appearing at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, because it could not guarantee his safety.[8]

Republican Party nomination[]

| 1968 Republican Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard Nixon | Spiro Agnew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36th Vice President of the United States (1953–1961) |

55th Governor of Maryland (1967–1969) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other major candidates[]

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their flying home delegation in the case of favorite sons.

Nixon received 1,679,443 votes in the primaries.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the nomination race | |||

| Ronald Reagan | Nelson Rockefeller | Harold Stassen | George W. Romney |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Governor of California (1967–1975) |

Governor of New York (1959–1973) |

Fmr. President of the University of Pennsylvania (1948–1953) |

Governor of Michigan (1963–1969) |

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | |

| Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 1,696,632 votes |

Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 164,340 votes |

Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 31,665 votes |

Withdrew: February 28, 1968 4,447 votes |

Primaries[]

The front-runner for the Republican nomination was former Vice President Richard Nixon, who formally began campaigning in January 1968.[9] Nixon had worked tirelessly behind the scenes and was instrumental in Republican gains in Congress and governorships in the 1966 midterm elections. Thus, the party machinery and many of the new congressmen and governors supported him. Still, there was wariness in the Republican ranks over Nixon, who had lost the 1960 election and then lost the 1962 California gubernatorial election. Some hoped a more "electable" candidate would emerge. The story of the 1968 Republican primary campaign and nomination may be seen as one Nixon opponent after another entering the race and then dropping out. Nixon was the front runner throughout the contest because of his superior organization, and he easily defeated the rest of the field.

Nixon's first challenger was Michigan Governor George W. Romney. A Gallup poll in mid-1967 showed Nixon with 39%, followed by Romney with 25%. After a fact-finding trip to Vietnam, Romney told Detroit talk show host Lou Gordon that he had been "brainwashed" by the military and the diplomatic corps into supporting the Vietnam War; the remark led to weeks of ridicule in the national news media. Turning against American involvement in Vietnam, Romney planned to run as the anti-war Republican version of Eugene McCarthy.[10] But, following his "brainwashing" comment, Romney's support faded steadily; with polls showing him far behind Nixon, he withdrew from the race on February 28, 1968.[11]

United States Senator Charles Percy was considered another potential threat to Nixon, and had planned on waging an active campaign after securing a role as Illinois's favorite son. Later, however, Percy declined to have his name listed on the ballot for the Illinois presidential primary. He no longer sought the presidential nomination.[12]

Nixon won a resounding victory in the important New Hampshire primary on March 12, with 78% of the vote. Anti-war Republicans wrote in the name of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the leader of the Republican Party's liberal wing, who received 11% of the vote and became Nixon's new challenger. Rockefeller had not originally intended to run, having discounted a campaign for the nomination in 1965, and planned to make United States Senator Jacob Javits, the favorite son, either in preparation of a presidential campaign or to secure him the second spot on the ticket. As Rockefeller warmed to the idea of entering the race, Javits shifted his effort to seeking a third term in the Senate.[13] Nixon led Rockefeller in the polls throughout the primary campaign, and though Rockefeller defeated Nixon and Governor John Volpe from Massachusetts primary on April 30, he otherwise fared poorly in state primaries and conventions. He had declared too late to get his name placed on state primary ballots.

By early spring, California Governor Ronald Reagan, the leader of the Republican Party's conservative wing, had become Nixon's chief rival. In the Nebraska primary on May 14, Nixon won with 70% of the vote to 21% for Reagan and 5% for Rockefeller. While this was a wide margin for Nixon, Reagan remained Nixon's leading challenger. Nixon won the next primary of importance, Oregon, on May 15 with 65% of the vote, and won all the following primaries except for California (June 4), where only Reagan appeared on the ballot. Reagan's victory in California gave him a plurality of the nationwide primary vote, but his poor showing in most other state primaries left him far behind Nixon in the delegate count.

Total popular vote:

|

|

Republican Convention[]

As the 1968 Republican National Convention opened on August 5 in Miami Beach, Florida, the Associated Press estimated that Nixon had 656 delegate votes – 11 short of the number he needed to win the nomination. Reagan and Rockefeller were his only remaining opponents and they planned to unite their forces in a "stop-Nixon" movement.

Because Goldwater had done well in the Deep South, delegates to the 1968 Republican National Convention included more Southern conservatives than in past conventions. There seemed potential for the conservative Reagan to be nominated if no victor emerged on the first ballot. Nixon narrowly secured the nomination on the first ballot, with the aid of South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched parties in 1964.[14][page needed] He selected dark horse Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party, appealing to both Northern moderates and Southerners disaffected with the Democrats.[15] Nixon's first choice for running mate was reportedly his longtime friend and ally Robert Finch, who was the Lieutenant Governor of California at the time. Finch declined that offer, but accepted an appointment as the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in Nixon's administration. With Vietnam a key issue, Nixon had strongly considered tapping his 1960 running mate, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., a former U.S. senator, ambassador to the UN, and ambassador twice to South Vietnam.

Candidates for the Vice-Presidential nomination:

|

|

| President | (before switches) | (after switches) | Vice President | Vice-Presidential votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richard M. Nixon | 692 | 1238 | Spiro T. Agnew | 1119 |

| Nelson Rockefeller | 277 | 93 | George Romney | 186 |

| Ronald Reagan | 182 | 2 | John V. Lindsay | 10 |

| Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes | 55 | — | Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke | 1 |

| Michigan Governor George Romney | 50 | — | James A. Rhodes | 1 |

| New Jersey Senator Clifford Case | 22 | — | Not Voting | 16 |

| Kansas Senator Frank Carlson | 20 | — | — | |

| Arkansas Governor Winthrop Rockefeller | 18 | — | — | |

| Hawaii Senator Hiram Fong | 14 | — | — | |

| Harold Stassen | 2 | — | — | |

| New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay | 1 | — | — |

As of the 2020 presidential election, 1968 was the last time that two siblings (Nelson and Winthrop Rockefeller) ran against each other in a Presidential primary.

Democratic Party nomination[]

| 1968 Democratic Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hubert Humphrey | Edmund Muskie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38th Vice President of the United States (1965–1969) |

U.S. Senator from Maine (1959–1980) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other major candidates[]

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their home delegation in the case of favorite sons.

Humphrey received 166,463 votes in the primaries.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the nomination race | ||||||||

| Eugene McCarthy | George McGovern | Channing E. Phillips | Lester Maddox | Robert F. Kennedy | Lyndon B. Johnson | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| U.S. Senator from Minnesota (1959–1971) |

U.S. Senator from South Dakota (1963–1981) |

Reverend at Lincoln Temple from Washington, D.C. |

Governor of Georgia (1967–1971) |

U.S. Senator from New York (1965–1968) |

U.S. President (1963–1969) | |||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||

| Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 2,914,933 votes |

Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 0 votes |

Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 0 votes |

Withdrew and endorsed George Wallace: August 28, 1968 0 votes |

Assassinated: June 5, 1968 2,305,148 votes |

Withdrew: March 31, 1968 383,590 votes | |||

Enter Eugene McCarthy[]

Because Lyndon B. Johnson had been elected to the presidency only once, in 1964, and had served less than two full years of the term before that, the 22nd Amendment did not disqualify him from running for another term.[17][18] As a result, it was widely assumed when 1968 began that President Johnson would run for another term, and that he would have little trouble winning the Democratic nomination.

Despite growing opposition to Johnson's policies in Vietnam, it appeared that no prominent Democratic candidate would run against a sitting president of his own party. It was also accepted at the beginning of the year that Johnson's record of domestic accomplishments would overshadow public opposition to the Vietnam War and that he would easily boost his public image after he started campaigning.[19] Even United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy from New York, an outspoken critic of Johnson's policies with a large base of support, publicly declined to run against Johnson in the primaries. Poll numbers also suggested that a large share of Americans who opposed the Vietnam War felt the growth of the anti-war hippie movement among younger Americans and violent unrest on college campuses was not helping their cause.[19] On January 30, however, claims by the Johnson administration that a recent troop surge would soon bring an end to the war were severely discredited when the Tet Offensive broke out. Although the American military was eventually able to fend off the attacks, and also inflict heavy losses among the communist opposition, the ability of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong to launch large scale attacks during the Tet Offensive's long duration greatly weakened American support for the military draft and further combat operations in Vietnam.[20] A recorded phone conversation which Johnson had with Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley on January 27 revealed that both men had become aware of Kennedy's private intention to enter the Democratic presidential primaries and that Johnson was willing to accept Daley's offer to run as Humphrey's vice president if he were to end his re-election campaign.[21] Daley, whose city would host the 1968 Democratic National Convention, also preferred either Johnson or Humphrey over any other candidate and stated that Kennedy had met him the week before, and that he was unsuccessful in his attempt to win over Daley's support.[21]

In time, only United States Senator Eugene McCarthy from Minnesota proved willing to challenge Johnson openly. Running as an anti-war candidate in the New Hampshire primary, McCarthy hoped to pressure the Democrats into publicly opposing the Vietnam War. Since New Hampshire was the first presidential primary of 1968, McCarthy poured most of his limited resources into the state. He was boosted by thousands of young college students led by youth coordinator Sam Brown,[22] who shaved their beards and cut their hair to be "Clean for Gene". These students organized get-out-the-vote drives, rang doorbells, distributed McCarthy buttons and leaflets, and worked hard in New Hampshire for McCarthy. On March 12, McCarthy won 42 percent of the primary vote to Johnson's 49 percent, a shockingly strong showing against an incumbent president, which was even more impressive because Johnson had more than 24 supporters running for the Democratic National Convention delegate slots to be filled in the election, while McCarthy's campaign organized more strategically, McCarthy won 20 of the 24 delegates. This gave McCarthy's campaign legitimacy and momentum.

Sensing Johnson's vulnerability, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced his candidacy four days after the New Hampshire primary. Thereafter, McCarthy and Kennedy engaged in a series of state primaries. Despite Kennedy's high profile, McCarthy won most of the early primaries, including Kennedy's native state of Massachusetts and some primaries in which he and Kennedy were in direct competition.[23][24] Following his victory in the key battleground state of Oregon, it was assumed that McCarthy was the preferred choice among the young voters.[25]

Johnson withdraws[]

On March 31, 1968, following the New Hampshire primary and Kennedy's entry into the election, the president made a televised speech to the nation and said that he was suspending all bombing of North Vietnam in favor of peace talks. After concluding his speech, Johnson announced,

"With America's sons in the fields far away, with America's future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world's hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office—the presidency of your country. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President."

Not discussed publicly at the time was Johnson's concern that he might not survive another term—Johnson's health was poor, and he had already suffered a serious heart attack in 1955. He died on January 22, 1973, two days after the end of the new presidential term. Bleak political forecasts also contributed to Johnson's withdrawal; internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin, the next state to hold a primary election, showed the President trailing badly.[26]

Historians have debated why Johnson quit a few days after his weak showing in New Hampshire. Jeff Shesol says Johnson wanted out of the White House but also wanted vindication; when the indicators turned negative, he decided to leave.[27] Lewis L. Gould says that Johnson had neglected the Democratic party, was hurting it by his Vietnam policies, and underestimated McCarthy's strength until the last minute, when it was too late for Johnson to recover.[28] Randall Bennett Woods said Johnson realized he needed to leave in order for the nation to heal.[29] Robert Dallek writes that Johnson had no further domestic goals, and realized that his personality had eroded his popularity. His health was poor, and he was preoccupied with the Kennedy campaign; his wife was pressing for his retirement and his base of support continued to shrink. Leaving the race would allow him to pose as a peacemaker.[30] Anthony J. Bennett, however, said Johnson "had been forced out of a re-election race in 1968 by outrage over his policy in Southeast Asia".[31]

In 2009 an AP reporter said that Johnson decided to end his re-election bid after CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, who was influential, turned against the president's policy in Vietnam. During a CBS News editorial which aired on February 27, Cronkite recommended the US pursue peace negotiations.[32][33] After watching Cronkite's editorial, Johnson allegedly exclaimed "if I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America."[32] This quote by Johnson has been disputed for accuracy.[34] Johnson was attending Texas Governor John Connally's birthday gala in Austin, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired and did not see the original broadcast.[34] But, Cronkite and CBS News correspondent Bob Schieffer defended reports that the remark had been made. They said that members of Johnson's inner circle, who had watched the editorial with the president, including presidential aide George Christian and journalist Bill Moyers, later confirmed the accuracy of the quote to them.[35][36] Schieffer, who was a reporter for the Star-Telegram's WBAP television station in Fort Worth, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired, acknowledged reports that the president saw the editorial's original broadcast were inaccurate,[36] but claimed the president was able to watch a taping of it the morning after it aired and then made the remark.[36] However, Johnson's January 27, 1968 phone conversion with Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley revealed that the two were trying to feed Robert Kennedy's ego so he would stay in the race, convincing him that the Democratic Party was undergoing a "revolution."[21] They suggested he might earn a spot as vice president.[21]

After Johnson's withdrawal, the Democratic Party quickly split into four factions.

- The first faction consisted of labor unions and big-city party bosses (led by Mayor Richard J. Daley). This group had traditionally controlled the Democratic Party since the days of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and they feared loss of their control over the party. After Johnson's withdrawal this group rallied to support Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's vice-president; it was also believed that President Johnson himself was covertly supporting Humphrey, despite his public claims of neutrality.

- The second faction, which rallied behind Senator Eugene McCarthy, was composed of college students, intellectuals, and upper-middle-class whites who had been the early activists against the war in Vietnam; they perceived themselves as the future of the Democratic Party.

- The third group was primarily composed of black people, Chicanos, and other minorities, as well as several anti-war groups; these groups rallied behind Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

- The fourth group consisted of white Southern Democrats. Some older voters, remembering the New Deal's positive impact upon the rural South, supported Vice-President Humphrey. Many would rally behind the third-party campaign of former Alabama Governor George Wallace as a "law and order" candidate.

Since the Vietnam War had become the major issue that was dividing the Democratic Party, and Johnson had come to symbolize the war for many liberal Democrats, Johnson believed that he could not win the nomination without a major struggle, and that he would probably lose the election in November to the Republicans. However, by withdrawing from the race he could avoid the stigma of defeat, and he could keep control of the party machinery by giving the nomination to Humphrey, who had been a loyal vice-president.[37] Milne (2011) argues that, in terms of foreign-policy in the Vietnam War, Johnson at the end wanted Nixon to be president rather than Humphrey, since Johnson agreed with Nixon, rather than Humphrey, on the need to defend South Vietnam from communism.[38] However, Johnson's telephone calls show that Johnson believed the Nixon camp was deliberately sabotaging the Paris peace talks. He told Humphrey, who refused to use allegations based on illegal wiretaps of a presidential candidate. Nixon himself called Johnson and denied the allegations. Dallek concludes that Nixon's advice to Saigon made no difference, and that Humphrey was so closely identified with Johnson's unpopular policies that no last-minute deal with Hanoi could have affected the election.[39]

Contest[]

After Johnson's withdrawal, Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced his candidacy. Kennedy was successful in four state primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California) and McCarthy won six (Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Oregon, New Jersey, and Illinois). However, in primaries where they campaigned directly against one another, Kennedy won three primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, and California) and McCarthy won one (Oregon).[40] Humphrey did not compete in the primaries, leaving that job to favorite sons who were his surrogates, notably United States Senator George A. Smathers from Florida, United States Senator Stephen M. Young from Ohio, and Governor Roger D. Branigin of Indiana. Instead, Humphrey concentrated on winning the delegates in non-primary states, where party leaders such as Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley controlled the delegate votes in their states. Kennedy defeated Branigin and McCarthy in the Indiana primary, and then defeated McCarthy in the Nebraska primary. However, McCarthy upset Kennedy in the Oregon primary.

After Kennedy's defeat in Oregon, the California primary was seen as crucial to both Kennedy and McCarthy. McCarthy stumped the state's many colleges and universities, where he was treated as a hero for being the first presidential candidate to oppose the war. Kennedy campaigned in the ghettos and barrios of the state's larger cities, where he was mobbed by enthusiastic supporters. Kennedy and McCarthy engaged in a television debate a few days before the primary; it was generally considered a draw. On June 4, Kennedy narrowly defeated McCarthy in California, 46%–42%. However, McCarthy refused to withdraw from the race and made it clear that he would contest Kennedy in the upcoming New York primary, where McCarthy had much support from anti-war activists in New York City. The New York primary quickly became a moot point, however, for Kennedy was assassinated shortly after midnight on June 5; he died twenty-six hours later at Good Samaritan Hospital. Kennedy had just given his victory speech in a crowded ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles; he and his aides then entered a narrow kitchen pantry on their way to a banquet room to meet with reporters. In the pantry Kennedy and five others were shot by Sirhan Sirhan, a 24-year-old Rosicrucian Palestinian of Christian background and Jordanian citizenship, who hated Kennedy because of his support for Israel. Sirhan admitted his guilt, was convicted of murder, and is still in prison.[41] In recent years some have cast doubt on Sirhan's guilt, including Sirhan himself, who said he was "brainwashed" into killing Kennedy and was a patsy.[42]

Political historians still debate whether Kennedy could have won the Democratic nomination had he lived. Some historians, such as Theodore H. White and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., have argued that Kennedy's broad appeal and famed charisma would have convinced the party bosses at the Democratic Convention to give him the nomination. Jack Newfield, author of RFK: A Memoir, stated in a 1998 interview that on the night he was assassinated, "[Kennedy] had a phone conversation with Mayor Daley of Chicago, and Mayor Daley all but promised to throw the Illinois delegates to Bobby at the convention in August 1968. I think he said to me, and Pete Hamill, 'Daley is the ball game, and I think we have Daley.'"[43] However, other writers such as Tom Wicker, who covered the Kennedy campaign for The New York Times, believe that Humphrey's large lead in delegate votes from non-primary states, combined with Senator McCarthy's refusal to quit the race, would have prevented Kennedy from ever winning a majority at the Democratic Convention, and that Humphrey would have been the Democratic nominee even if Kennedy had lived. The journalist Richard Reeves and historian Michael Beschloss have both written that Humphrey was the likely nominee, and future Democratic National Committee chairman Larry O'Brien wrote in his memoirs that Kennedy's chances of winning the nomination had been slim, even after his win in California.

At the moment of RFK's death, the delegate totals were:

- Hubert Humphrey 561

- Robert F. Kennedy 393

- Eugene McCarthy 258

Total popular vote:[44]

|

|

Democratic Convention and antiwar protests[]

Robert Kennedy's death altered the dynamics of the race. Although Humphrey appeared the presumptive favorite for the nomination, thanks to his support from the traditional power blocs of the party, he was an unpopular choice with many of the anti-war elements within the party, who identified him with Johnson's controversial position on the Vietnam War. However, Kennedy's delegates failed to unite behind a single candidate who could have prevented Humphrey from getting the nomination. Some of Kennedy's support went to McCarthy, but many of Kennedy's delegates, remembering their bitter primary battles with McCarthy, refused to vote for him. Instead, these delegates rallied around the late-starting candidacy of Senator George McGovern of South Dakota, a Kennedy supporter in the spring primaries who had presidential ambitions himself. This division of the anti-war votes at the Democratic Convention made it easier for Humphrey to gather the delegates he needed to win the nomination.

When the 1968 Democratic National Convention opened in Chicago, thousands of young activists from around the nation gathered in the city to protest the Vietnam War. On the evening of August 28, in a clash which was covered on live television, Americans were shocked to see Chicago police brutally beating anti-war protesters in the streets of Chicago in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel. While the protesters chanted "the whole world is watching", the police used clubs and tear gas to beat back or arrest the protesters, leaving many of them bloody and dazed. The tear gas wafted into numerous hotel suites; in one of them Vice President Humphrey was watching the proceedings on television. The police said that their actions were justified because numerous police officers were being injured by bottles, rocks, and broken glass that were being thrown at them by the protestors. The protestors had also yelled insults at the police, calling them "pigs" and other epithets. The anti-war and police riot divided the Democratic Party's base: some supported the protestors and felt that the police were being heavy-handed, but others disapproved of the violence and supported the police. Meanwhile, the convention itself was marred by the strong-arm tactics of Chicago's mayor Richard J. Daley (who was seen on television angrily cursing Senator Abraham Ribicoff from Connecticut, who made a speech at the convention denouncing the excesses of the Chicago police). In the end, the nomination itself was anti-climactic, with Vice-President Humphrey handily beating McCarthy and McGovern on the first ballot.

After the delegates nominated Humphrey, the convention then turned to selecting a vice-presidential nominee. The main candidates for this position were Senators Edward M. Kennedy from Massachusetts, Edmund Muskie from Maine, and Fred R. Harris from Oklahoma; Governors Richard Hughes of New Jersey and Terry Sanford of North Carolina; Mayor Joseph Alioto of San Francisco, California; former Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance; and Ambassador Sargent Shriver from Maryland. Another idea floated was to tap Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, one of the most liberal Republicans. Ted Kennedy was Humphrey's first choice, but the senator turned him down. After narrowing it down to Senator Muskie and Senator Harris, Vice-President Humphrey chose Muskie, a moderate and environmentalist from Maine, for the nomination. The convention complied with the request and nominated Senator Muskie as Humphrey's running mate.

The publicity from the anti-war riots crippled Humphrey's campaign from the start, and it never fully recovered.[45] Before 1968 the city of Chicago had been a frequent host for the political conventions of both parties; since 1968 only one national convention has been held there (the Democratic convention of 1996, which nominated Bill Clinton for a second term).

| Presidential tally | Vice Presidential tally | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hubert Humphrey | 1759.25 | Edmund S. Muskie | 1942.5 |

| Eugene McCarthy | 601 | Not Voting | 604.25 |

| George S. McGovern | 146.5 | Julian Bond | 48.5 |

| Channing Phillips | 67.5 | David Hoeh | 4 |

| Daniel K. Moore | 17.5 | Edward M. Kennedy | 3.5 |

| Edward M. Kennedy | 12.75 | Eugene McCarthy | 3.0 |

| Paul W. "Bear" Bryant | 1.5 | Others | 16.25 |

| James H. Gray | 0.5 | ||

| George Wallace | 0.5 | ||

Source: Keating Holland, "All the Votes... Really," CNN[46]

Endorsements[]

Hubert Humphrey

- President Lyndon B. Johnson

- Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago

- Former President Harry S. Truman

- Singer/actor Frank Sinatra

Robert F. Kennedy

- Senator Abraham Ribicoff from Connecticut[44]

- Senator George McGovern from South Dakota[47]

- Governor Harold E. Hughes of Iowa[48]

- Senator Vance Hartke from Indiana[44]

- Labor Leader Cesar Chavez[44]

- Writer Truman Capote[49]

- Writer Norman Mailer[44]

- Actress Shirley MacLaine[49]

- Actress Stefanie Powers

- Actor Robert Vaughn[50]

- Actor Peter Lawford

- Singer Bobby Darin[51]

Eugene McCarthy

- Representative Don Edwards from California[44]

- Actor Paul Newman[44]

- Actress Tallulah Bankhead[49]

- Playwright Arthur Miller[49]

- Writer William Styron[49]

George McGovern (during convention)

American Independent Party nomination of George Wallace[]

| American Independent Party Ticket, 1968 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George Wallace | Curtis LeMay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45th Governor of Alabama (1963–1967) |

General of the U.S. Air Force (1951–1965) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The American Independent Party, which was established in 1967 by Bill and Eileen Shearer, nominated former Alabama Governor George Wallace – whose pro-racial segregation policies had been rejected by the mainstream of the Democratic Party – as the party's candidate for president. The impact of the Wallace campaign was substantial, winning the electoral votes of several states in the Deep South. He appeared on the ballot in all fifty states, but not the District of Columbia. Although he did not come close to winning any states outside the South, Wallace was the most popular 1968 presidential candidate among young men.[53] Wallace also proved to be popular among blue-collar workers in the North and Midwest, and he took many votes which might have gone to Humphrey.[54]

Wallace was not expected to win the election – his strategy was to prevent either major party candidate from winning a preliminary majority in the Electoral College. Although Wallace put considerable effort into mounting a serious general election campaign, his presidential bid was also a continuation of Southern efforts to elect unpledged electors that had taken place in every election from 1956 – he had his electors promise to vote not necessarily for him but rather for whomever he directed them to support – his objective was not to move the election into the U.S. House of Representatives where he would have had little influence, but rather to give himself the bargaining power to determine the winner. Wallace's running mate was retired four star General Curtis LeMay.

Prior to deciding on LeMay, Wallace gave serious consideration to former U.S. senator, governor, and Baseball Commissioner A.B. Happy Chandler of Kentucky as his running mate.[55] Chandler and Wallace met a number of times; however, Chandler said that he and Wallace were unable to come to an agreement regarding their positions on racial matters. Paradoxically, Chandler supported the segregationist Dixiecrats in the 1948 presidential elections. However, after being reelected Governor of Kentucky in 1955, he used National Guard troops to enforce school integration.[56]

LeMay embarrassed Wallace's campaign in the fall by suggesting that nuclear weapons could be used in Vietnam.

Other parties and candidates[]

Also on the ballot in two or more states were black activist Eldridge Cleaver (who was ineligible to take office, as he would have only been 33 years of age on January 20, 1969) for the Peace and Freedom Party; Henning Blomen for the Socialist Labor Party; Fred Halstead for the Socialist Workers Party; E. Harold Munn for the Prohibition Party; and Charlene Mitchell – the first African-American woman to run for president, and the first woman to receive valid votes in a general election – for the Communist Party. Comedians Dick Gregory and Pat Paulsen were notable write-in candidates. A facetious presidential candidate for 1968 was a pig named Pigasus, as a political statement by the Yippies, to illustrate their premise that "one pig's as good as any other."[57][page needed]

General election[]

Campaign strategies[]

Nixon developed a "Southern strategy" that was designed to appeal to conservative white southerners, who had traditionally voted Democratic, but were opposed to Johnson and Humphrey's support for the civil rights movement, as well as the rioting that had broken out in the ghettos of most large cities. Wallace, however, won over many of the voters Nixon targeted, effectively splitting that voting bloc. Indeed, Wallace deliberately targeted many states he had little chance of carrying himself in the hope that by splitting as many votes with Nixon as possible he would give competitive states to Humphrey and, by extension, boost his own chances of denying both opponents an Electoral College majority.[58]

Since he was well behind Nixon in the polls as the campaign began, Humphrey opted for a slashing, fighting campaign style. He repeatedly – and unsuccessfully – challenged Nixon to a televised debate, and he often compared his campaign to the successful underdog effort of President Harry Truman, another Democrat who had trailed in the polls, in the 1948 presidential election. Humphrey predicted that he, like Truman, would surprise the experts and win an upset victory.[59]

Campaign themes[]

Nixon campaigned on a theme to restore "law and order,"[60] which appealed to many voters angry with the hundreds of violent riots that had taken place across the country in the previous few years. Following the murder of Martin Luther King in April 1968, there was massive rioting in inner city areas. The police were overwhelmed and President Johnson had to call out the U.S. Army. Nixon also opposed forced busing to desegregate schools.[61] Proclaiming himself a supporter of civil rights, he recommended education as the solution rather than militancy. During the campaign, Nixon proposed government tax incentives to African Americans for small businesses and home improvements in their existing neighborhoods.[62]

During the campaign, Nixon also used as a theme his opposition to the decisions of Chief Justice Earl Warren. Many conservatives were critical of Chief Justice Warren for using the Supreme Court to promote liberal policies in the fields of civil rights, civil liberties, and the separation of church and state. Nixon promised that if he were elected president, he would appoint justices who would take a less-active role in creating social policy.[63] In another campaign promise, he pledged to end the draft.[64] During the 1960s, Nixon had been impressed by a paper he had read by Professor Martin Anderson of Columbia University. Anderson had argued in the paper for an end to the draft and the creation of an all-volunteer army.[65] Nixon also saw ending the draft as an effective way to undermine the anti-Vietnam war movement, since he believed affluent college-age youths would stop protesting the war once their own possibility of having to fight in it was gone.[66]

Humphrey, meanwhile, promised to continue and expand the Great Society welfare programs started by President Johnson, and to continue the Johnson Administration's "War on Poverty." He also promised to continue the efforts of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and the Supreme Court, in promoting the expansion of civil rights and civil liberties for minority groups. However, Humphrey also felt constrained for most of his campaign in voicing any opposition to the Vietnam War policies of President Johnson, due to his fear that Johnson would reject any peace proposals he made and undermine his campaign. As a result, early in his campaign Humphrey often found himself the target of anti-war protestors, some of whom heckled and disrupted his campaign rallies.

Humphrey's comeback and the October surprise[]

After the Democratic Convention in late August, Humphrey trailed Nixon by double digits in most polls, and his chances seemed hopeless. Many within Humphrey's campaign saw their real goal as avoiding the potential humiliation of finishing behind Wallace in the electoral college vote (if not necessarily the popular vote), rather than having any serious chance of defeating Nixon. According to Time magazine, "The old Democratic coalition was disintegrating, with untold numbers of blue-collar workers responding to Wallace's blandishments, Negroes threatening to sit out the election, liberals disaffected over the Vietnam War, the South lost. The war chest was almost empty, and the party's machinery, neglected by Lyndon Johnson, creaked in disrepair."[67] Calling for "the politics of joy," and using the still-powerful labor unions as his base, Humphrey fought back. In order to distance himself from Johnson and to take advantage of the Democratic plurality in voter registration, Humphrey stopped being identified in ads as "Vice-President Hubert Humphrey," instead being labelled "Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey." Humphrey attacked Wallace as a racist bigot who appealed to the darker impulses of Americans. Wallace had been rising in the polls, and peaked at 21% in September, but his momentum stopped after he selected Curtis LeMay as his running mate. Curtis LeMay's suggestion of tactical nuclear weapons being used in Vietnam conjured up memories of the 1964 Goldwater campaign.[14] Labor unions also undertook a major effort to win back union members who were supporting Wallace, with substantial success. Polls that showed Wallace winning almost one-half of union members in the summer of 1968 showed a sharp decline in his union support as the campaign progressed. As election day approached and Wallace's support in the North and Midwest began to wane, Humphrey finally began to climb in the polls.

In October, Humphrey—who was rising sharply in the polls due to the collapse of the Wallace vote—began to distance himself publicly from the Johnson administration on the Vietnam War, calling for a bombing halt. The key turning point for Humphrey's campaign came when President Johnson officially announced a bombing halt, and even a possible peace deal, the weekend before the election. The "Halloween Peace" gave Humphrey's campaign a badly needed boost. In addition, Senator Eugene McCarthy finally endorsed Humphrey in late October after previously refusing to do so, and by election day the polls were reporting a dead heat.[68]

Nixon campaign sabotage of peace talks[]

The Nixon campaign had anticipated a possible "October surprise," a peace agreement produced by the Paris negotiations; as such an agreement would be a boost to Humphrey, Nixon thwarted any last-minute chances of a "Halloween Peace." Nixon told campaign aide and his future White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman to put a "monkey wrench" into an early end to the war.[69] Johnson was enraged and said that Nixon had "blood on his hands" and that Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen agreed with Johnson that such action was "treason."[70][71] Defense Secretary Clark Clifford considered the moves an illegal violation of the Logan Act.[72] A former director of the Nixon Library called it a "covert action" which "laid the skulduggery of his presidency."[69]

Bryce Harlow, former Eisenhower White House staff member, claimed to have "a double agent working in the White House....I kept Nixon informed." Harlow and Nixon's future National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who was friendly with both campaigns and guaranteed a job in either a Humphrey or Nixon administration, separately predicted Johnson's "bombing halt": "The word is out that we are making an effort to throw the election to Humphrey. Nixon has been told of it," Democratic senator George Smathers informed Johnson.[73]

Nixon asked Anna Chennault to be his "channel to Mr. Thieu" in order to advise him to refuse participation in the talks, in what is sometimes described as the "Anna Chennault Affair."[74] Thieu was promised a better deal under a Nixon administration.[75][74] Chennault agreed and periodically reported to John Mitchell that Thieu had no intention of attending a peace conference. On November 2, Chennault informed the South Vietnamese ambassador: "I have just heard from my boss in Albuquerque who says his boss [Nixon] is going to win. And you tell your boss [Thieu] to hold on a while longer." In 1997, Chennault admitted that "I was constantly in touch with Nixon and Mitchell."[76] The effort also involved Texas Senator John Tower and Kissinger, who traveled to Paris on behalf of the Nixon campaign. William Bundy stated that Kissinger obtained "no useful inside information" from his trip to Paris, and "almost any experienced Hanoi watcher might have come to the same conclusion". While Kissinger may have "hinted that his advice was based on contacts with the Paris delegation," this sort of "self-promotion....is at worst a minor and not uncommon practice, quite different from getting and reporting real secrets."[77]

Johnson learned of the Nixon-Chennault effort because the NSA was intercepting communications in Vietnam.[78] In response, Johnson ordered NSA surveillance of Chennault and wire-tapped the South Vietnamese embassy and members of the Nixon campaign.[79] He did not leak the information to the public because he did not want to "shock America" with the revelation,[80] nor reveal that the NSA was intercepting communications in Vietnam.[81] Johnson did make information available to Humphrey, but at this point Humphrey thought he was going to win the election, so he did not reveal the information to the public. Humphrey later regretted this as a mistake.[82] The South Vietnamese government withdrew from peace negotiations, and Nixon publicly offered to go to Saigon to help the negotiations.[83] A promising "peace bump" ended up in "shambles" for the Democratic Party.[81]

Election[]

The election on November 5, 1968, proved to be extremely close, and it was not until the following morning that the television news networks were able to declare Nixon the winner. The key states proved to be California, Ohio, and Illinois, all of which Nixon won by three percentage points or less. Had Humphrey carried all three of these states, he would have won the election. Had he carried only two of them or just California among them, George Wallace would have succeeded in his aim of preventing an electoral college majority for any candidate, and the decision would have been given to the House of Representatives, at the time controlled by the Democratic Party. Nixon won the popular vote with a plurality of 512,000 votes, or a victory margin of about one percentage point. In the electoral college Nixon's victory was larger, as he carried 32 states with 301 electoral votes, compared to Humphrey's 13 states and 191 electoral votes and Wallace's five states and 46 electoral votes.[84]

Out of all the states that Nixon had previously carried in 1960, Maine and Washington were the only two states that did not vote for him again; Nixon carried them during his re-election campaign in 1972. He also carried eight states that voted for John F. Kennedy in 1960: Illinois, New Jersey, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, New Mexico, Nevada and Delaware. This was the last time until 1988 that the state of Washington voted Democratic and until 1992 that Connecticut, Maine, and Michigan voted Democratic in the general election. Nixon was also the last Republican candidate to win a presidential election without carrying Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. This is the first time which the Republican candidate captured the White House without carrying Michigan, Minnesota, Maine and Pennsylvania. He would be the last Republican candidate to carry Minnesota (four years later, in 1972), as of 2020.[2] This is also the first time since 1916 that Minnesota voted for the candidate who did not eventually win.[85]

Remarkably, Nixon won the election despite winning only two of the six states (Arizona and South Carolina) won by Republican Barry Goldwater four years earlier. He remains the only presidential candidate to win in spite of defending such a low number of his own party's states. All of the remaining four States carried by Goldwater were carried by Wallace in 1968. They would be won by Nixon in 1972.[84][2]

Of the 3,130 counties/districts/independent cities making returns, Nixon won in 1,859 (59.39%) while Humphrey carried 693 (22.14%). Wallace was victorious in 578 counties (18.47%), all of which (with one exception of Pemiscot County, Missouri) were located in the South.[84]

Nixon said that Humphrey left a gracious message congratulating him, noting, "I know exactly how he felt. I know how it feels to lose a close one."[86]

Results[]

Nixon's victory is often considered a realigning election in American politics. From 1932 to 1964, the Democratic Party was undoubtedly the majority party, winning seven out of nine presidential elections, and their agenda influenced policies undertaken by the Republican Eisenhower administration. The 1968 election reversed the situation completely. From 1968 until 2004, Republicans won seven out of ten presidential elections, and its policies clearly affected those enacted by the Democratic Clinton administration via the Third Way.[87][2]

The election was a seismic event in the long-term realignment in Democratic Party support, especially in the South.[88] Nationwide, the bitter splits over civil rights, the new left, the Vietnam War, and other "culture wars" were slow to heal. Democrats could no longer count on white Southern support for the presidency, as Republicans made major gains in suburban areas and areas filled with Northern migrants.[89] The rural Democratic "courthouse cliques" in the South lost power. While Democrats controlled local and state politics in the South, Republicans usually won the presidential vote. In 1968, Humphrey won less than ten percent of the white Southern vote, with two-thirds of his vote in the region coming from blacks, who now voted in full strength.[90]

From 1968 until 2004, only two Democrats were elected president, both native Southerners – Jimmy Carter of Georgia and Bill Clinton of Arkansas. Not until 2008 did a Northern Democrat, Barack Obama of Illinois, again win a presidential election.[2][91]

Another important result of this election was that it led to several reforms in how the Democratic Party chose its presidential nominees. In 1969, the McGovern–Fraser Commission adopted a set of rules for the states to follow in selecting convention delegates. These rules reduced the influence of party leaders on the nominating process and provided greater representation for minorities, women, and youth. The reforms led most states to adopt laws requiring primary elections, instead of party leaders, to choose delegates.[92]

After 1968, the only way to win the party's presidential nomination became through the primary process; Humphrey turned out to be the last nominee of either major party to win his party's nomination without having directly competed in the primaries.

This remains most recent presidential election in which a sitting president eligible for re-election did not seek another term (and one of only two such elections to occur under the Twenty-second Amendment, the first being the 1952 election), and also the last election in which any third-party candidate won an entire state's electoral votes, with Wallace carrying five states.[2]

This election was the last time until 1992 that the Democratic nominee won Connecticut, Maine, and Michigan and the last until 1988 when Washington voted Democrat, and the last time a Republican won the presidency without winning Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.[2] It was also the first time since 1888 that bellwether Coös County, New Hampshire did not support the winning candidate.[93]

This was the first time since 1928 that North Carolina voted for a Republican, and the first since 1912 (only the second time since 1852 and as of 2020, the last time) that Maine and Vermont did not support same party. Similarly, it is the last time that Oregon and Washington did not support the same party, meaning the two neighbouring states have only voted for different candidates twice in 100 years.

Despite the narrow (0.7%) difference in the popular vote, Humphrey took only 35.5% of the electoral vote. This disparity prompted the introduction of the Bayh–Celler amendment in Congress, which would have replaced the Electoral College with a direct election of the presidency. The effort was not successful and the Electoral College is still in force.[94]

Results[]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Richard Milhous Nixon | Republican | New York[a] | 31,783,783 | 43.42% | 301 | Spiro Theodore Agnew | Maryland | 301 |

| Hubert Horatio Humphrey | Democratic | Minnesota | 31,271,839 | 42.72% | 191 | Edmund Sixtus Muskie | Maine | 191 |

| George Corley Wallace | American Independent | Alabama | 9,901,118 | 13.53% | 46[95] | Curtis Emerson LeMay | California[96] | 46[95] |

| Other | 243,258 | 0.33% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 73,199,998 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1968 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved August 7, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

Geography of results[]

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery[]

Presidential election results by county

Republican presidential election results by county

Democratic presidential election results by county

American Independent presidential election results by county

"Other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of American Independent presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Results by state[]

| States/districts won by Nixon/Agnew |

| States/districts won by Humphrey/Muskie |

| States/districts won by Wallace/LeMay |

| Richard Nixon Republican |

Hubert H. Humphrey Democratic |

George Wallace American Independent |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 10 | 146,923 | 13.99 | - | 196,579 | 18.72 | - | 691,425 | 65.86 | 10 | -494,846 | -47.13 | 1,049,917 | AL |

| Alaska | 3 | 37,600 | 45.28 | 3 | 35,411 | 42.65 | - | 10,024 | 12.07 | - | 2,189 | 2.64 | 83,035 | AK |

| Arizona | 5 | 266,721 | 54.78 | 5 | 170,514 | 35.02 | - | 46,573 | 9.56 | - | 96,207 | 19.76 | 486,936 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 6 | 189,062 | 31.01 | - | 184,901 | 30.33 | - | 235,627 | 38.65 | 6 | -46,565 | -7.64 | 609,590 | AR |

| California | 40 | 3,467,664 | 47.82 | 40 | 3,244,318 | 44.74 | - | 487,270 | 6.72 | - | 223,346 | 3.08 | 7,251,587 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 409,345 | 50.46 | 6 | 335,174 | 41.32 | - | 60,813 | 7.50 | - | 74,171 | 9.14 | 811,199 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 556,721 | 44.32 | - | 621,561 | 49.48 | 8 | 76,650 | 6.10 | - | -64,840 | -5.16 | 1,256,232 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 96,714 | 45.12 | 3 | 89,194 | 41.61 | - | 28,459 | 13.28 | - | 7,520 | 3.51 | 214,367 | DE |

| D.C. | 3 | 31,012 | 18.18 | - | 139,566 | 81.82 | 3 | - | - | - | -108,554 | -63.64 | 170,578 | DC |

| Florida | 14 | 886,804 | 40.53 | 14 | 676,794 | 30.93 | - | 624,207 | 28.53 | - | 210,010 | 9.60 | 2,187,805 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 380,111 | 30.40 | - | 334,440 | 26.75 | - | 535,550 | 42.83 | 12 | -155,439 | -12.43 | 1,250,266 | GA |

| Hawaii | 4 | 91,425 | 38.70 | - | 141,324 | 59.83 | 4 | 3,469 | 1.47 | - | -49,899 | -21.12 | 236,218 | HI |

| Idaho | 4 | 165,369 | 56.79 | 4 | 89,273 | 30.66 | - | 36,541 | 12.55 | - | 76,096 | 26.13 | 291,183 | ID |

| Illinois | 26 | 2,174,774 | 47.08 | 26 | 2,039,814 | 44.15 | - | 390,958 | 8.46 | - | 134,960 | 2.92 | 4,619,749 | IL |

| Indiana | 13 | 1,067,885 | 50.29 | 13 | 806,659 | 37.99 | - | 243,108 | 11.45 | - | 261,226 | 12.30 | 2,123,597 | IN |

| Iowa | 9 | 619,106 | 53.01 | 9 | 476,699 | 40.82 | - | 66,422 | 5.69 | - | 142,407 | 12.19 | 1,167,931 | IA |

| Kansas | 7 | 478,674 | 54.84 | 7 | 302,996 | 34.72 | - | 88,921 | 10.19 | - | 175,678 | 20.13 | 872,783 | KS |

| Kentucky | 9 | 462,411 | 43.79 | 9 | 397,541 | 37.65 | - | 193,098 | 18.29 | - | 64,870 | 6.14 | 1,055,893 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 257,535 | 23.47 | - | 309,615 | 28.21 | - | 530,300 | 48.32 | 10 | -220,685 | -20.11 | 1,097,450 | LA |

| Maine | 4 | 169,254 | 43.07 | - | 217,312 | 55.30 | 4 | 6,370 | 1.62 | - | -48,058 | -12.23 | 392,936 | ME |

| Maryland | 10 | 517,995 | 41.94 | - | 538,310 | 43.59 | 10 | 178,734 | 14.47 | - | -20,315 | -1.64 | 1,235,039 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 766,844 | 32.89 | - | 1,469,218 | 63.01 | 14 | 87,088 | 3.73 | - | -702,374 | -30.12 | 2,331,752 | MA |

| Michigan | 21 | 1,370,665 | 41.46 | - | 1,593,082 | 48.18 | 21 | 331,968 | 10.04 | - | -222,417 | -6.73 | 3,306,250 | MI |

| Minnesota | 10 | 658,643 | 41.46 | - | 857,738 | 54.00 | 10 | 68,931 | 4.34 | - | -199,095 | -12.53 | 1,588,510 | MN |

| Mississippi | 7 | 88,516 | 13.52 | - | 150,644 | 23.02 | - | 415,349 | 63.46 | 7 | -264,705 | -40.44 | 654,509 | MS |

| Missouri | 12 | 811,932 | 44.87 | 12 | 791,444 | 43.74 | - | 206,126 | 11.39 | - | 20,488 | 1.13 | 1,809,502 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 138,835 | 50.60 | 4 | 114,117 | 41.59 | - | 20,015 | 7.29 | - | 24,718 | 9.01 | 274,404 | MT |

| Nebraska | 5 | 321,163 | 59.82 | 5 | 170,784 | 31.81 | - | 44,904 | 8.36 | - | 150,379 | 28.01 | 536,851 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 73,188 | 47.46 | 3 | 60,598 | 39.29 | - | 20,432 | 13.25 | - | 12,590 | 8.16 | 154,218 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 154,903 | 52.10 | 4 | 130,589 | 43.93 | - | 11,173 | 3.76 | - | 24,314 | 8.18 | 297,298 | NH |

| New Jersey | 17 | 1,325,467 | 46.10 | 17 | 1,264,206 | 43.97 | - | 262,187 | 9.12 | - | 61,261 | 2.13 | 2,875,395 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 4 | 169,692 | 51.85 | 4 | 130,081 | 39.75 | - | 25,737 | 7.86 | - | 39,611 | 12.10 | 327,281 | NM |

| New York | 43 | 3,007,932 | 44.30 | - | 3,378,470 | 49.76 | 43 | 358,864 | 5.29 | - | -370,538 | -5.46 | 6,790,066 | NY |

| North Carolina | 13 | 627,192 | 39.51 | 12 | 464,113 | 29.24 | - | 496,188 | 31.26 | 1 | 131,004 | 8.25 | 1,587,493 | NC |

| North Dakota | 4 | 138,669 | 55.94 | 4 | 94,769 | 38.23 | - | 14,244 | 5.75 | - | 43,900 | 17.71 | 247,882 | ND |

| Ohio | 26 | 1,791,014 | 45.23 | 26 | 1,700,586 | 42.95 | - | 467,495 | 11.81 | - | 90,428 | 2.28 | 3,959,698 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 449,697 | 47.68 | 8 | 301,658 | 31.99 | - | 191,731 | 20.33 | - | 148,039 | 15.70 | 943,086 | OK |

| Oregon | 6 | 408,433 | 49.83 | 6 | 358,866 | 43.78 | - | 49,683 | 6.06 | - | 49,567 | 6.05 | 819,622 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 29 | 2,090,017 | 44.02 | - | 2,259,405 | 47.59 | 29 | 378,582 | 7.97 | - | -169,388 | -3.57 | 4,747,928 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 122,359 | 31.78 | - | 246,518 | 64.03 | 4 | 15,678 | 4.07 | - | -124,159 | -32.25 | 385,000 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 254,062 | 38.09 | 8 | 197,486 | 29.61 | - | 215,430 | 32.30 | - | 38,632 | 5.79 | 666,982 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 149,841 | 53.27 | 4 | 118,023 | 41.96 | - | 13,400 | 4.76 | - | 31,818 | 11.31 | 281,264 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 472,592 | 37.85 | 11 | 351,233 | 28.13 | - | 424,792 | 34.02 | - | 47,800 | 3.83 | 1,248,617 | TN |

| Texas | 25 | 1,227,844 | 39.87 | - | 1,266,804 | 41.14 | 25 | 584,269 | 18.97 | - | -38,960 | -1.27 | 3,079,406 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 238,728 | 56.49 | 4 | 156,665 | 37.07 | - | 26,906 | 6.37 | - | 82,063 | 19.42 | 422,568 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 85,142 | 52.75 | 3 | 70,255 | 43.53 | - | 5,104 | 3.16 | - | 14,887 | 9.22 | 161,404 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 590,319 | 43.36 | 12 | 442,387 | 32.49 | - | 321,833 | 23.64 | - | 147,932 | 10.87 | 1,361,491 | VA |

| Washington | 9 | 588,510 | 45.12 | - | 616,037 | 47.23 | 9 | 96,990 | 7.44 | - | -27,527 | -2.11 | 1,304,281 | WA |

| West Virginia | 7 | 307,555 | 40.78 | - | 374,091 | 49.60 | 7 | 72,560 | 9.62 | - | -66,536 | -8.82 | 754,206 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 809,997 | 47.89 | 12 | 748,804 | 44.27 | - | 127,835 | 7.56 | - | 61,193 | 3.62 | 1,691,538 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 70,927 | 55.76 | 3 | 45,173 | 35.51 | - | 11,105 | 8.73 | - | 25,754 | 20.25 | 127,205 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 538 | 31,783,783 | 43.42 | 301 | 31,271,839 | 42.72 | 191 | 9,901,118 | 13.53 | 46 | 511,944 | 0.70 | 73,199,998 | US |

Close states[]

States where margin of victory was less than 5 percentage points (223 electoral votes):

|

States where margin of victory was more than 5 percentage points, but less than 10 percentage points (155 electoral votes):

|

Notes: In Alabama, Wallace was the official Democratic Party nominee, while Humphrey ran on the ticket of short-lived National Democratic Party of Alabama, loyal to him as an official Democratic Party nominee[98][99]

In North Carolina one Nixon Elector cast his ballot for George Wallace (President) and Curtis LeMay (Vice President).[100]

Statistics[]

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Hooker County, Nebraska 87.94%

- Jackson County, Kentucky 84.09%

- McIntosh County, North Dakota 82.65%

- McPherson County, South Dakota 80.34%

- Sioux County, Iowa 80.04%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Duval County, Texas 88.74%

- Jim Hogg County, Texas 82.06%

- Washington, D.C. 81.82%

- Webb County, Texas 79.65%

- Suffolk County, Massachusetts 75.62%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (American Independent)

- Geneva County, Alabama 91.73%

- George County, Mississippi 91.20%

- Lamar County, Alabama 88.25%

- Calhoun County, Mississippi 87.80%

- Holmes County, Florida 87.21%

National voter demographics[]

| NBC sample precincts 1968 election | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Humphrey | % Nixon | % Wallace | |

| High income urban | 32 | 63 | 5 |

| Middle income urban | 43 | 44 | 13 |

| Low income urban | 69 | 19 | 12 |

| Rural (all income) | 33 | 46 | 21 |

| African-American neighborhoods | 94 | 5 | 1 |

| Italian neighborhoods | 51 | 39 | 10 |

| Slavic neighborhoods | 65 | 24 | 11 |

| Jewish neighborhoods | 81 | 17 | 2 |

| Unionized neighborhoods | 61 | 29 | 10 |

Source: Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report. "Group Analysis of the 1968 Presidential Vote" XXVI, No. 48 (November 1968), p. 3218.

Voter demographics in the South[]

| NBC sample precincts 1968 election: South only | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Humphrey | % Nixon | % Wallace | |

| Middle income urban neighborhoods | 28 | 40 | 32 |

| Low income urban neighborhoods | 57 | 18 | 25 |

| Rural (all income) | 29 | 30 | 41 |

| African-American neighborhoods | 95 | 3 | 2 |

| Hispanic neighborhoods | 92 | 7 | 1 |

Source: Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report. "Group Analysis of the 1968 Presidential Vote", XXVI, No. 48 (November 1968), p. 3218.

See also[]

- 1968 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1968 United States Senate elections

- 1968 United States gubernatorial elections

- History of the United States (1964–1980)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- List of presidents of the United States

- First inauguration of Richard Nixon

Sources[]

- White, Theodore H., The Making of the President 1968. Pocket Books, 1970.

References[]

- ^ "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Historical U.S. Presidential Elections 1789-2016". www.270towin.com. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Voting Rights Act of 1965". HISTORY. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ Azari, Julia (August 20, 2020). "Biden Had To Fight For The Presidential Nomination. But Most VPs Have To". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ Thomas Adams Upchurch, Race relations in the United States, 1960–1980 (2008) pp. 7–50.

- ^ "A Timeline of 1968: The Year That Shattered America". Smithsonian. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ James Westheider (2011). Fighting in Vietnam: The Experience of the US Soldier. Stackpole Books. pp. 136–38. ISBN 978-0-8117-0831-9.

- ^ Ben J. Wattenberg (2008). Fighting Words: A Tale of How Liberals Created Neo-Conservatism. Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4299-2463-4.

- ^ "Another Race To the Finish". The News & Observer. November 2, 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ The New York Times, February 18, 1968

- ^ The New York Times, February 29, 1968

- ^ "PERCY SHUNNING ACTIVE '68 ROLE – Wants to Stay Off Ballot in Presidential Primaries". The New York Times. September 26, 1967. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "Javits Says Favorite-Son Choice For '68 Is Still an Open Matter". September 29, 1967. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Perlstein 2008.

- ^ "1968 Year In Review". UPI. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "1968 | Presidential Campaigns & Elections Reference". Presidentialcampaignselectionsreference.wordpress.com. July 5, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Johnson Can Seek Two Full Terms". The Washington Post. November 24, 1963. p. A2.

- ^ Moore, William (November 24, 1963). "Law Permits 2 Full Terms for Johnson". The Chicago Tribune. p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Man Of The Year: Lyndon B. Johnson, The Paradox of Power". Time Magazine. January 5, 1968. Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ "Jan 30, 1968: Tet Offensive shakes Cold War confidence". History.com:This Day In History. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "LBJ and Richard Daley, 1/27/68, 10.58A" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Sam Brown discussing his involvement in the "Clean for Gene" campaign. WGBH Open Vault. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ George Rising (1997). Clean for Gene: Eugene McCarthy's 1968 Presidential Campaign. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-275-95841-1.

- ^ "1968: Eugene McCarthy". April 7, 2018.

- ^ Perry, Douglas (May 16, 2016). "Robert F. Kennedy's epic battle for Oregon: Historic photos". oregonlive.

- ^ "Could Trump Lose the Republican Nomination? Here's the History of Primary Challenges to Incumbent Presidents". Time.

- ^ Jeff Shesol (1998). Mutual Contempt: Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy, and the Feud that Defined a Decade. W W Norton. pp. 545–47. ISBN 978-0-393-31855-5.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould (2010). 1968: The Election That Changed America. Government Institutes. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-1-56663-910-1.

- ^ Randall Bennett Woods (2007). LBJ: architect of American ambition. Harvard University Press. pp. 834–35. ISBN 978-0-674-02699-5.

- ^ Robert Dallek (1998). Flawed Giant:Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973. Oxford University Press. pp. 518–25. ISBN 978-0-19-982670-4.

- ^ Anthony J. Bennett (2013). The Race for the White House from Reagan to Clinton: Reforming Old Systems, Building New Coalitions. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-137-26860-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moore, Frazier (July 18, 2009). "Legendary CBS anchor Walter Cronkite dies at 92". GMA News. Associated Press. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Wicker, Tom (January 26, 1997). "Broadcast News". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campbell, W. Joseph (July 9, 2012). "Chris Matthews invokes the 'if I've lost Cronkite' myth in NYT review". Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Walter Cronkite (1996). A Reporter's Life. Ballantine Books. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-394-57879-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bob Schieffer (January 6, 2004). This Just In: What I Couldn't Tell You on TV. Putnam Pub Group. ISBN 978-0-399-14971-9. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Dallek (1998); Woods (2006); Gould (1993).

- ^ David (1968). "Paris peace negotiations: a two level game?". Review of International Studies. 37 (2): 577–599.

- ^ Robert Dallek, Nixon and Kissinger (2009) p 77

- ^ Cook, Rhodes (2000). United States Presidential Primary Elections 1968–1996: A Handbook of Election Statistics. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-56802-451-6.

- ^ Abbe A. Debolt; James S. Baugess (2011). Encyclopedia of the Sixties: A Decade of Culture and Counterculture. ABC-CLIO. p. 607. ISBN 978-1-4408-0102-0.

- ^ "Sirhan Sirhan Seeks Release Or New Trial – TalkLeft: The Politics Of Crime". TalkLeft. November 27, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

"Top stories from Canada and around the world |MSN Headlines". News.ca.msn.com. August 2, 2015. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

Greenhill, Abby (November 28, 2011). "Sirhan Sirhan Says He Didn't Kill Bobby Kennedy in 1968 – Gather.com : Gather.com". News.gather.com. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

[1] Archived May 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine - ^ Jack Newfield, interview with Terry Gross, Fresh Air from WHYY, National Public Radio, WHYY, Philadelphia, June 4, 1998. Excerpt rebroadcast on June 4, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Our Campaigns – US President – D Primaries Race – Mar 12, 1968". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "White, pp. 377–378". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "AllPolitics – 1996 GOP NRC – All The Votes...Really". Cnn.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "Our Campaigns – SD US President – D Primary Race – Jun 04, 1968". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "Our Campaigns – Candidate – Harold Everett Hughes". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. (1978). "Robert Kennedy and His Times". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Our Campaigns – CA US President – D Primary Race – Jun 04, 1968". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "BobbyDarin.net/BobbyDarin.com – Bobby Darin & Bobby Kennedy". Bobbydarin.net. May 10, 1968. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Our Campaigns – US President – D Convention Race – Aug 26, 1968". Ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York: Basic Books. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-465-04195-4.

- ^ B. Dan Wood; Soren Jordan (2017). Party Polarization in America: The War Over Two Social Contracts. p. 165. ISBN 9781108171212.

- ^ Hill, John Paul (December 16, 2002). "A. B. "Happy" Chandler, George C. Wallace, and the Presidential Election of 1968". The Historian. 64 (34): 667–685. doi:10.1111/1540-6563.00010. S2CID 145329893.

- ^ "Happy Chandler | biography – American politician and baseball commissioner". Britannica.com. June 15, 1991. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America.

- ^ Joseph A. Aistrup, The southern strategy revisited: Republican top-down advancement in the South (2015).

- ^ Daniel S. Margolies (2012). A Companion to Harry S. Truman. p. 264. ISBN 9781118300756.

- ^ Greenberg, David (October 22, 2001). "Civil Rights: Let 'Em Wiretap!". History News Network.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-465-04195-4.

- ^ Conrad Black, (2007), p. 525.

- ^ Laura Kalman (1990). Abe Fortas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04669-4. Retrieved October 20, 2008.