Black Friday bushfires

| Black Friday bushfires | |

|---|---|

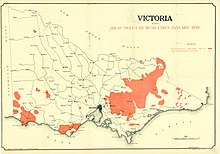

A map of Victoria showing the impact of the Black Friday bushfires as shaded, that burnt on 13 January 1939. (Source: State Library of Victoria) | |

| Location | Victoria, Australia |

| Statistics | |

| Date(s) | 13 January 1939 |

| Burned area | 2,000,000 hectares (4,900,000 acres) |

| Cause |

|

| Buildings destroyed | 650 |

| Deaths | 71 |

The Black Friday bushfires of 13 January 1939, in Victoria, Australia, were part of the devastating 1938–1939 bushfire season in Australia, which saw bushfires burning for the whole summer, and ash falling as far away as New Zealand. It was calculated that three-quarters of the State of Victoria was directly or indirectly affected by the disaster, while other Australian states and the Australian Capital Territory were also badly hit by fires and extreme heat. As of 3 November 2011, the event was one of the worst[clarification needed] recorded bushfires in Australia, and the third most deadly.[1]

Fires burned almost 2,000,000 hectares (4,900,000 acres) of land in Victoria, where 71 people were killed, and several towns were entirely obliterated. Over 1,300 homes and 69 sawmills were burned, and 3,700 buildings were destroyed or damaged.[2] In response, the Victorian state government convened a Royal Commission that resulted in major changes in forest management. The Royal Commission noted that "it appeared the whole State was alight on Friday, 13 January 1939".[3]

New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory also faced severe fires during the 1939 season. Destructive fires burned from the NSW South Coast, across the ranges and inland to Bathurst, while Sydney was ringed by fires which entered the outer suburbs, and fires raged towards the new capital at Canberra.[4] South Australia was also struck by the Adelaide Hills bushfires.

Conditions[]

Eastern Australia is one of the most fire-prone regions of the world, with predominant eucalyptus forests that have evolved to thrive on the phenomenon of bushfire.[5] However, the 1938-9 bushfire season was exacerbated by a period of extreme heat, following several years of drought. Extreme heatwaves were accompanied by strong northerly winds, after a very dry six months.[6] In the days preceding the fires, the Victorian state capital, Melbourne, experienced some of its hottest temperatures on record at the time: 43.8 °C (110.8 °F) on 8 January and 44.7 °C (112.5 °F) on 10 January. On 13 January, the day of the fires, temperatures reached 45.6 °C (114.1 °F), which stood as the hottest day officially recorded in Melbourne for the next 70 years. (Unofficial records show temperatures of around 47 °C (117 °F) were reported on the Black Thursday fires of 6 February 1851).[7]

The subsequent Victorian Royal Commission investigation of the fires recorded that Victoria had not seen such dry conditions for more than two decades, and its rich plains lay "bare and baking; and the forest, from the foothills to the alpine heights, were tinder". The people who made their lives in the bush were worried by the dry conditions, but "had not lived long enough" to imagine what was to come: " the most disastrous forest calamity the State of Victoria has known." Fires had been burning separately across Victoria through December, but reached a new intensity and "joined forces in a terrible confluence of flame...".[2]:Introduction - Part 1on Friday, 13 January.

Effects in Victoria[]

The most damage was felt in the mountain and alpine areas in the northeast and around the southwest coast. The Acheron, Tanjil and Thomson Valleys and the Grampians, were also hit. Five townships – Hill End, Narbethong, , Noojee (apart from the Hotel), Woods Point – were completely destroyed and not all were rebuilt afterwards. The towns of Omeo, Pomonal, Warrandyte (though this is now a suburb of Melbourne, it was not in 1939) and Yarra Glen were also badly damaged.[citation needed]

The Stretton Royal Commission wrote:[2]:Introduction - Part 1

"On [13 January] it appeared that the whole State was alight. At midday, in many places, it was dark as night. Men carrying hurricane lamps, worked to make safe their families and belongings. Travellers on the highways were trapped by fires or blazing fallen trees, and perished. Throughout the land there was daytime darkness... Steel girders and machinery were twisted by heat as if they had been of fine wire. Sleepers of heavy durable timber, set in the soil, their upper surfaces flush with the ground, were burnt through... Where the fire was most intense the soil was burnt to such a depth that it may be many years before it shall have been restored..."

— Stretton Royal Commission.

An area of almost two million hectares (four point nine million acres) burned, 71 people killed, and whole townships wiped out, along with many sawmills and thousands of sheep, cattle and horses. According to Forest Management Victoria, during the bushfires of 13 January 1939:

"[F]lames leapt large distances, giant trees were blown out of the ground by fierce winds and large pieces of burning bark (embers) were carried for kilometres ahead of the main fire front, starting new fires in places that had not previously been affected by flames... The townships of Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Omeo and Pomonal were badly damaged. Intense fires burned on the urban fringe of Melbourne in the Yarra Ranges east of Melbourne, affecting towns including Toolangi, Warburton and Thomson Valley. The alpine towns of Bright, Cudgewa and Corryong were also affected, as were vast areas in the west of the state, in particular Portland, the Otway Ranges and the Grampians. The bushfires also affected the Black Range, Rubicon, Acheron, Noojee, Tanjil Bren, Hill End, Woods Point, Matlock, Erica, Omeo, Toombullup and the Black Forest. Large areas of state forest, containing giant stands of Mountain Ash and other valuable timbers, were killed. Approximately 575,000 hectares of reserved forest, and 780,000 hectares of forested Crown land were burned. The intensity of the fire produced huge amounts of smoke and ash, with reports of ash falling as far away as New Zealand".

— Forest Management Victoria.[8]

Major fires[]

There were five major fire areas. Smaller fires included; East Gippsland, Mount Macedon, Mallee and the Mornington Peninsula. The major fires, listed roughly in order of size, included;

- Victorian Alps/Yarra Ranges

- Portland

- Otway Ranges

- Grampians

- Strzelecki Ranges

Towns damaged or destroyed[]

- Central

- Dromana

- Healesville

- Kinglake

- Marysville

- Narbethong – destroyed

- Warburton

- Warrandyte

- Yarra Glen

- East

- Hill End – destroyed

- – destroyed

- Matlock – 15 died at a sawmill

- Noojee – destroyed

- Omeo

- Woods Point – destroyed

- West

- Pomonal

- Portland

Stretton Royal Commission and long-term consequences[]

The subsequent Royal Commission, under Judge Leonard Edward Bishop Stretton (known as the Stretton Inquiry), attributed blame for the fires to careless burning, campfires, graziers, sawmillers and land clearing.

Prior to 13 January 1939, many fires were already burning. Some of the fires started as early as December 1938, but most of them started in the first week of January 1939. Some of these fires could not be extinguished. Others were left unattended or, as Judge Stretton wrote, the fires were allowed to burn "under control", as it was falsely and dangerously called. Stretton declared that most of the fires were lit by the "hand of man".[2][8]

Stretton's Royal Commission has been described as one of the most significant inquiries in the history of Victorian public administration.[9]

As a consequence of Judge Stretton's scathing report, the Forests Commission Victoria gained additional funding and took responsibility for fire protection on all public land including State forests, unoccupied Crown Lands and National Parks, plus a buffer extending one mile beyond their boundaries on to private land. Its responsibilities grew in one leap from 2.4 to 6.5 million hectares (5.9 to 16.1 million acres). Stretton's recommendations officially sanctioned and encouraged the common bush practice of controlled burning to minimise future risks.[2]

Its recommendations led to sweeping changes, including stringent regulation of burning and fire safety measures for sawmills, grazing licensees and the general public, the compulsory construction of dugouts at forest sawmills, increasing the forest roads network and firebreaks, construction of forest dams, fire towers and RAAF aerial patrols linked by the Commissions radio network VL3AA[10] to ground observers.[2] The Commission's communication systems were regarded at the time as being more technically advanced than those of the police and the military. These pioneering efforts were directed by Geoff Weste.[11]

Victoria's forests were devastated to an extent that was unprecedented within living memory, and the impact of the 1939 bushfires dominated management thought and action for much of the next ten years.[12] Salvage of fire-killed timber became an urgent and dominant task that was still consuming the resources and efforts of the Forests Commission a decade and a half later.

It was estimated that over 6 million cubic meters of timber needed to be salvaged. This massive task was made more difficult by labour shortages caused by the Second World War. In fact, there was so much material that some of the logs were harvested and stockpiled in huge dumps in creek beds and covered with soil and treeferns to stop them from cracking, only to be recovered many years later.[11]

Further major fires later in the 1943–44 Victorian bushfire season and another Royal Commission by Judge Stretton were key factors in the founding of the Country Fire Authority (CFA) for fire suppression on rural land.[9] Prior to the creation of the CFA the Forests Commission had, to some extent, been supporting the individual volunteer brigades that had formed across rural Victoria in the preceding decades.[9]

The environmental effects of the fires continued for many years and some of the burnt dead trees still remain today. Large areas of animal habitat were destroyed. In affected areas, the soil took decades to recover from the damage of the fires. In some areas, water supplies were contaminated for some years afterwards due to ash and debris washing into catchment areas.

Fires in other states[]

Other states also suffered severely in the extreme heat and fires. In New South Wales, Bourke suffered 37 consecutive days above 38 °C (100 °F) and Menindee hit a record 49.7 °C (121.5 °F) on 10 January. In mid-January, Sydney was ringed to the north, south and west by bushfires - from Palm Beach and Port Hacking to the Blue Mountains.[6]

- New South Wales

Following the weekend of Black Friday, The Argus reported that on 15 January, fierce winds had also spread fire to almost every important area of New South Wales, burning in major fronts on Sydney's suburban fringes and hitting the south coast and inland: "hundreds of houses and thousands of head of stock and poultry were destroyed and thousands of acres of grazing land".[13]

On 16 January, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that disastrous fires were burning in Victoria, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory as the climax to the terrible heatwave: Sydney faced record heat and was ringed to the north, south and west by bushfires from Palm Beach and Port Hacking to the Blue Mountains, with fires blazing at Castle Hill, Sylvania, Cronulla and French's Forest.[4][6] Disastrous fires were reported at Penrose, Wollongong, Nowra, Bathurst, Ulludulla, Mittagong, Trunkey and Nelligen.[4]

- Australian Capital Territory

Canberra was facing the "worst bushfires" it had experienced, with thousands of acres burned out and a 72-kilometre (45 mi) fire front was driven towards the city by a south westerly gale, destroying pine plantations and many homesteads, and threatening Mount Stromlo Observatory, Government House, and Black Mountain. Large numbers of men were sent to stand by government buildings in the line of fire. While five deaths in New South Wales were reported, in Victoria the death toll had reached more than sixty.[4]

- South Australia

In South Australia, the Adelaide Hills bushfires also swept the state, destroying dozens of buildings.[14]

Comparison with other major bushfires[]

Internationally, south-eastern Australia is considered one of the three most fire-prone landscapes on Earth, along with southern California and the southern Mediterranean.[15] Major Victorian bushfires occurred on Black Thursday in 1851, where an estimated 5 million hectares (12 million acres) were burnt, followed by another blaze on Red Tuesday in February 1891 in South Gippsland when about 260,000 hectares (640,000 acres) were burnt, 12 people died and more than 2,000 buildings were destroyed. The deadly pattern continued with more major fires on Black Sunday on 14 February 1926 sees the tally rise to sixty lives being lost and widespread damage to farms, homes and forests.

Considered in terms of both loss of property and loss of life the 1939 fires were one of the worst disasters, and certainly the worst bushfire event, to have occurred in Australia up to that time. Only the subsequent Ash Wednesday bushfires in 1983 and the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009 resulted in more deaths.[citation needed]

In terms of the total area burnt, the 1974–75 fires burned 117 million hectares (290 million acres), equivalent to 15% of Australia's land.;[16] the Black Friday fires burned up 2 million hectares (4.9 million acres), with the Black Thursday fires of 1851 having burnt an estimated 5 million hectares (12 million acres).

Putting aside large conflagrations of cities like the Great Fire of Meireki or the Great Fire of London, perhaps the world's worst wildfire was at Peshtigo in Wisconsin in 1871, which burnt nearly 0.49 million hectares (1.2 million acres), destroyed twelve communities and killed between 1,500–2,500 people. Now largely forgotten, Peshtigo was overshadowed by the Great Fire of Chicago that occurred on the same day.[citation needed]

See also[]

- List of disasters in Australia by death toll

- Ash Wednesday bushfires

- Black Saturday bushfires

- Black Thursday bushfires

- Country Fire Service (South Australia)

- Country Fire Authority (Victoria, Australia)

- New South Wales Rural Fire Service (Australia)

- Adelaide Hills bushfires

- Book: Forests of Ash by Tom Griffiths, published in 2002

References[]

- ^ Williams, Liz T. (3 November 2011). "The worst bushfires in Australia's history". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Stretton, Leonard Edward Bishop (1939). Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into the Causes of and Measures Taken to Prevent the Bush Fires of January, 1939, and to Protect Life and Property, and the Measures Taken to Prevent Bush Fires in Victoria and Protect Life and Property in the Event of Future Bush Fires (PDF). Parliament of Victoria: T. Rider, Acting Government Printer.

- ^ Lewis, Wendy; Balderstone, Simon; Bowan, John (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. pp. 154–158. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Terrible Climax to Heatwave". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 January 1939.

- ^ John Vandenbeld; Nature of Australia - Episode Three: The Making of the Bush; ABC video; 1988

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Lessons learnt (and perhaps forgotten) from Australia's 'worst fires'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 January 2019.

- ^ Argus Newspaper (Melbourne, Victoria), Saturday 28 June 1924

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Black Friday 1939". Forest Fire Management Victoria. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carron, L. T. (1985). A History of Forestry in Australia. Australian National University. ISBN 0080298745.

- ^ "Calling VL3AA".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moulds, F. R. (1991). The Dynamic Forest – A History of Forestry and Forest Industries in Victoria. Lynedoch Publications. Richmond, Australia. pp. 232pp. ISBN 0646062654.

- ^ "Fire ravaged forests saved by Victorian 10-year plan". The Australian Women's Weekly. 18 March 1950.

- ^ "Bush Fires Over Wide Area". The Argus. Melbourne. 16 January 1939.

- ^ "ADELAIDE HILLS AGAIN SWEPT BY FIRE". The Adelaide Chronicle. 19 January 1939 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- ^ Adams, M.; Attiwill, P. (2011). Burning Issues: Sustainability and management of Australia's southern forests. CSIRO Publishing/Bushfire CRC. pp. 144pp.

- ^ "New South Wales, December 1974 Bushfire - New South Wales". Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience. Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

Approximately 15 per cent of Australia's physical land mass sustained extensive fire damage. This equates to roughly around 117 million ha.

External links[]

- "Extracts of Judge Leonard Stretton's findings in the Royal Commission into the "Black Friday" 13 January 1939 fires". Australian Broadcasting Corporation online documentary about the 1939 Victorian bushfires. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- McHugh, Peter. (2020). Forests and Bushfire History of Victoria : A compilation of short stories, Victoria. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2899074696/view

- "Southern, Vic: Bushfires". EMA Disasters Database. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- Black Friday site on the ABC ABC site with comprehensive coverage of all aspects of the fires.

- Map of the area burnt by the 1939 bushfires

- State Library of Victoria's Bushfires in Victoria Research Guide Guide to locating books, government reports, websites, statistics, newspaper reports and images about the Black Friday fires.

- Royal Commission to Inquire into the Causes of and Measures Taken to Prevent the Bush Fires of January 1939 Digitised copy of the Royal Commission report, available from the State Library of Victoria's catalogue.

- Bushfires in Victoria (Australia)

- 1939 fires

- 1939 in Australia

- 1930s wildfires

- January 1939 events

- 1930s in Victoria (Australia)

- 1930s disasters in Australia