British Overseas Territories

British Overseas Territories | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

| Anthem: "God Save the Queen" | |

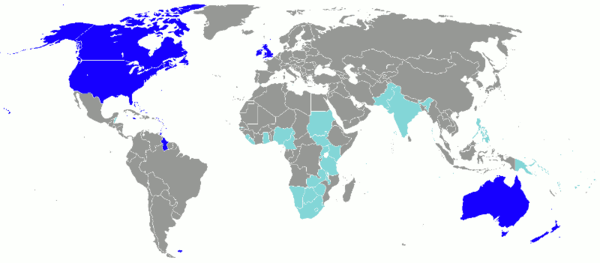

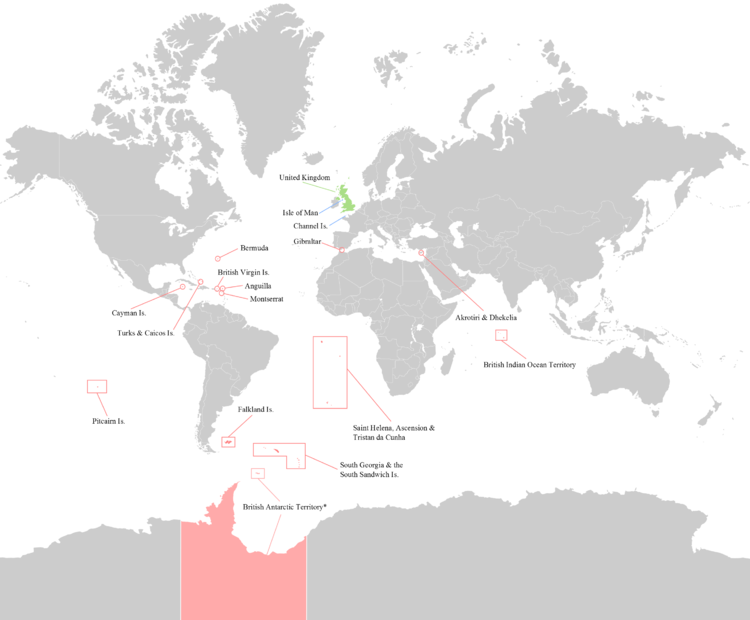

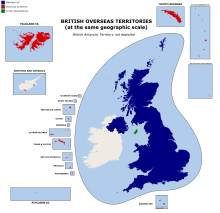

Location of the United Kingdom and the British Overseas Territories | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Largest territory | British Antarctic Territory |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Devolved administrations under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

• Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | Boris Johnson |

| Dominic Raab | |

• Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for European Neighbourhood and the Americas | Wendy Morton |

• Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development | Vacant (As of 25 November 2020) |

| Area | |

• Total | 18,015[a] km2 (6,956 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 272,256 |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories all with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom.[1][2] They are remnants of the British Empire and do not form part of the United Kingdom itself. Some of the permanently inhabited territories are internally self-governing, with the UK retaining responsibility for defence and foreign relations. Ten of the territories are listed by the UN Special Committee on Decolonization as non-self-governing territories. Three are inhabited only by a transitory population of military or scientific personnel. They all have the British monarch as head of state.[3][better source needed]

As of April 2018, three Territories (the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus) are the responsibility of the Minister of State for Europe and the Americas; the Minister responsible for the remaining Territories is the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development.[4]

Current overseas territories[]

The fourteen British Overseas Territories are:[5]

| Flag | Arms | Name | Location | Motto | Area | GDP (nominal) | GDP per capita (nominal) | Population | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | "Unity, Strength and Endurance" | 91 km2 (35.1 sq mi)[6] | $299 million | $20,307 | 14,869 (2019 estimate)[7] | The Valley | ||

| Bermuda | North Atlantic Ocean between the Azores, the Caribbean, Cape Sable Island in Canada, and Cape Hatteras (its nearest neighbour) in the United States | "Quo fata ferunt" (Latin; "Whither the Fates carry [us]") | 54 km2 (20.8 sq mi)[8] | $6.464 billion | $102,987 | 62,506 (2019 estimate)[9] | Hamilton | ||

| British Antarctic Territory | Antarctica | "Research and discovery" | 1,709,400 km2 (660,000 sq mi)[6] | 0 50 non-permanent in winter, over 400 in summer (research personnel)[10] |

Rothera (main base) | ||||

| British Indian Ocean Territory | Indian Ocean | "In tutela nostra Limuria" (Latin; "Limuria is in our charge") | 60 km2 (23 sq mi)[11] | 0 3,000 non-permanent (UK and US military and staff personnel; estimate)[12] |

Diego Garcia (base) | ||||

| British Virgin Islands | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | "Vigilate" (Latin; "Be watchful") | 153 km2 (59 sq mi)[13] | $1.05 billion | $48,511 | 31,758 (2018 census)[14] | Road Town | ||

| Cayman Islands | Caribbean | "He hath founded it upon the seas" | 264 km2 (101.9 sq mi)[15] | $4.298 billion | $85,474 | 68,076 (2019 estimate)[15] | George Town | ||

| Falkland Islands | South Atlantic Ocean | "Desire the right" | 12,173 km2 (4,700 sq mi)[8] | $164.5 million | $70,800 | 3,377 (2019 estimate)[16] 1,350 non-permanent (UK military personnel; 2012 estimate) |

Stanley | ||

| Gibraltar | Iberian Peninsula, Continental Europe | "Nulli expugnabilis hosti" (Latin; "No enemy shall expel us") | 6.5 km2 (2.5 sq mi)[17] | $3.08 billion | $92,843 | 33,701 (2019 estimate)[18] 1,250 non-permanent (UK military personnel; 2012 estimate) |

Gibraltar | ||

| Montserrat | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | "A people of excellence, moulded by nature, nurtured by God" | 101 km2 (39 sq mi)[19] | $61 million | $12,181 | 5,215 (2019 census)[20] | Plymouth (abandoned due to volcano—de facto capital is Brades) | ||

| Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands | Pacific Ocean | 47 km2 (18 sq mi)[21] | $144,715 | $2,894 | 50 (2018 estimate)[22] 6 non-permanent (2014 estimate)[23] |

Adamstown | |||

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, including: |

South Atlantic Ocean | 420 km2 (162 sq mi) | $55.7 million | $12,230 | 5,633 (total; 2016 census) | Jamestown | |||

| Saint Helena | "Loyal and Unshakeable" (Saint Helena) | 4,349 (Saint Helena; 2019 census)[24] | |||||||

| Ascension Island | 880 (Ascension; estimate)[25] 1,000 non-permanent (Ascension; UK military personnel; estimate)[25] |

||||||||

| Tristan da Cunha | "Our faith is our strength" (Tristan da Cunha) | 300 (Tristan da Cunha; estimate)[25] 9 non-permanent (Tristan da Cunha; weather personnel) |

|||||||

| South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands | South Atlantic Ocean | "Leo terram propriam protegat" (Latin; "Let the lion protect his own land") | 3,903 km2 (1,507 sq mi)[26] | 0 99 non-permanent (officials and research personnel)[27] |

King Edward Point | ||||

| Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia | Cyprus, Mediterranean Sea | 255 km2 (98 sq mi)[28] | 7,700 (Cypriots; estimate) 8,000 non-permanent (UK military personnel and their families; estimate) |

Episkopi Cantonment | |||||

| Turks and Caicos Islands | Lucayan Archipelago, North Atlantic Ocean | 430 km2 (166 sq mi)[29] | $1.077 billion | £28,589 | 38,191 (2019 estimate)[30] | Cockburn Town | |||

| Overall | c. 1,727,415 km2 [citation needed] |

c. $16.55 billion | c. 272,256[31] |

Map[]

Collective titles[]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

The term "British Overseas Territory" was introduced by the British Overseas Territories Act 2002, replacing the term British Dependent Territory, introduced by the British Nationality Act 1981. Prior to 1 January 1983, the territories were officially referred to as British Crown Colonies.

Although the Crown dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man are also under the sovereignty of the British monarch, they are in a different constitutional relationship with the United Kingdom.[33][34] The British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies are themselves distinct from the Commonwealth realms, a group of 16 independent countries (including the United Kingdom) each having Elizabeth II as their reigning monarch, and from the Commonwealth of Nations, a voluntary association of 53 countries mostly with historic links to the British Empire (which also includes all Commonwealth realms).

Population[]

With the exceptions of the British Antarctic Territory and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (which host only officials and research station staff) and the British Indian Ocean Territory (used as a military base), the Territories retain permanent civilian populations. Permanent residency for the approximately 7,000 civilians living in the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia is limited to citizens of the Republic of Cyprus[citation needed].

Collectively, the Territories encompass a population of about 250,000 people[31] and a land area of about 1,700,000 square kilometres (660,000 sq mi).[citation needed] The vast majority of this land area constitutes the almost uninhabited British Antarctic Territory (the land area of all the territories excepting the Antarctic territory is only 18,015 square kilometres (6,956 sq mi)), while the two largest territories by population, the Cayman Islands and Bermuda, account for about half of the total BOT population. At the other end of the scale, three territories have no civilian population; the Antarctic territory, the British Indian Ocean Territory (from which the Chagos Islanders were controversially removed) and South Georgia. Pitcairn Islands, settled by the survivors of the Mutiny on the Bounty, is the smallest settled territory with 49 inhabitants, while the smallest by land area is Gibraltar on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula.[35] The United Kingdom participates in the Antarctic Treaty System[36] and, as part of a mutual agreement, the British Antarctic Territory is recognised by four of the six other sovereign nations making claims to Antarctic territory.

History[]

Early colonies, in the sense of English subjects residing in lands hitherto outside the control of the English government, were generally known as "Plantations".

The first, unofficial, colony was Newfoundland, where English fishermen routinely set up seasonal camps in the 16th century.[38] It is now a province of Canada known as Newfoundland and Labrador. It retains strong cultural ties with Britain.

After failed attempts, including the Roanoke Colony, permanent English colonisation of North America began officially in 1607 with the settlement of Jamestown, the first successful permanent colony in Virginia (a term that was then applied generally to North America). Its offshoot, Bermuda, was settled inadvertently after the wrecking of the Virginia Company's flagship there in 1609, with the Virginia Company's charter extended to officially include the archipelago in 1612. St. George's town, founded in Bermuda in that year, remains the oldest continuously inhabited British settlement in the New World (with some historians stating that – its formation predating the 1619 conversion of "James Fort" into "Jamestown" – St. George's was actually the first successful town the English established in the New World). Bermuda and Bermudians have played important, sometimes pivotal, but generally underestimated or unacknowledged roles in the shaping of the English and British trans-Atlantic Empires. These include maritime commerce, settlement of the continent and of the West Indies, and the projection of naval power via the colony's privateers, among other areas.[39][40]

The growth of the British Empire in the 19th century, to its territorial peak in the 1920s, saw Britain acquire nearly one quarter of the world's land mass, including territories with large indigenous populations in Asia and Africa. From the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, the larger settler colonies – in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – first became self-governing colonies and then achieved independence in all matters except foreign policy, defence and trade. Separate self-governing colonies federated to become Canada (in 1867), Australia (in 1901), South Africa (in 1910), and Rhodesia (in 1965). These and other large self-governing colonies had become known as Dominions by the 1920s. The Dominions achieved almost full independence with the Statute of Westminster (1931).

Through a process of decolonisation following the Second World War, most of the British colonies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean chose independence. Some colonies became Commonwealth realms, retaining the British monarch as their own head of state.[41] Most former colonies and protectorates became member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, a non-political, voluntary association of equal members, comprising a population of around 2.2 billion people.[42]

After the independence of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in Africa in 1980 and British Honduras (now Belize) in Central America in 1981, the last major colony that remained was Hong Kong, with a population of over 5 million.[43] With 1997 approaching, the United Kingdom and China negotiated the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which led to the whole of Hong Kong becoming a "special administrative region" of China in 1997, subject to various conditions intended to guarantee the preservation of Hong Kong's capitalist economy and its way of life under British rule for at least 50 years after the handover. George Town in the Cayman Islands has consequently become the largest city in the Overseas Territories.

In 2002, the British Parliament passed the British Overseas Territories Act 2002. This reclassified the UK's dependent territories as overseas territories and, with the exception of those people solely connected with the Sovereign Base Areas of Cyprus, restored full British citizenship to their inhabitants.[44]

During the European Union (EU) membership of the UK the main body of EU law did not apply and, although certain slices of EU law were applied to the overseas territories as part of the EU's Association of Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT Association), they were not commonly enforceable in local courts. The OCT Association also provided overseas territories with structural funding for regeneration projects. Gibraltar was the only overseas territory that was part of the EU, although it was not part of the European Customs Union, the European Tax Policy, the European Statistics Zone or the Common Agriculture Policy. Gibraltar was not a member of the European Union in its own right, having had its representation in the European Parliament through its Members from South West England. Overseas citizens held concurrent European Union citizenship, having given them rights of free movement across all EU member states.

The Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus were never part of the European Union, but they are the only British overseas territory to use the Euro as official currency, having previously had the Cypriot pound as their currency until 1 January 2008.

Government[]

Head of state[]

The head of state in the overseas territories is the British monarch, Elizabeth II. The Queen's role in the territories is in her role as Queen of the United Kingdom, and not in right of each territory.[45] The Queen appoints a representative in each territory to exercise her executive power. In territories with a permanent population, a Governor is appointed by the Queen on the advice of the British Government. Currently (2019) all but two Governors are either career diplomats or have worked in other Civil Service departments. The remaining two Governors are former members of the British armed forces. In territories without a permanent population, a Commissioner is usually appointed to represent the Queen. Exceptionally, in the overseas territories of Saint Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha and the Pitcairn Islands, an Administrator is appointed to be the Governor's representative. In the territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, there is an Administrator in each of the two distant parts of the territory, namely Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha. The Administrator of the Pitcairn Islands resides on Pitcairn, with the Governor based in New Zealand.

The role of the Governor is to act as the de facto head of state, and they are usually responsible for appointing the head of government, and senior political positions in the territory. The Governor is also responsible for liaising with the UK Government, and carrying out any ceremonial duties. A Commissioner has the same powers as a Governor, but also acts as the head of government.[45]

Local government[]

All the overseas territories have their own system of government, and localised laws. The structure of the government appears to be closely correlated to the size and political development of the territory.[45]

| Territories | Government |

|---|---|

|

There is no native or permanent population; therefore there is no elected government. The Commissioner, supported by an Administrator, runs the affairs of the territory. |

|

There is no elected government, as there is no native settled population. The Chagos Islanders – who were forcibly evicted from the territory in 1971 – won a High Court Judgement allowing them to return, but this was then overridden by an Order in Council preventing them from returning. The final appeal to the House of Lords (regarding the lawfulness of the Order in Council) was decided in the government's favour, exhausting the islanders' legal options in the United Kingdom at present. |

|

There is no elected government. The Commander British Forces Cyprus acts as the territory's Administrator, with a Chief Officer responsible for day-to-day running of the civil government. As far as possible, there is convergence of laws[clarification needed] with those of the Republic of Cyprus. |

|

There are an elected Mayor and Island Council, who have the power to propose and administer local legislation. However, their decisions are subject to approval by the Governor, who retains near-unlimited powers of plenary legislation on behalf of the United Kingdom Government. |

|

The Government consists of an elected Legislative Assembly, with the Chief Executive and the Director of Corporate Resources as ex officio members.[46] |

|

The Government consists of an elected Legislative Council. The Governor is the head of government and leads the Executive Council, consisting of appointed members made up from the Legislative Council and two ex-officio members. Governance on Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha is led by Administrators who are advised by elected Island Councils.[47] |

|

These territories have a House of Assembly, Legislative Assembly (Cayman Islands and Montserrat), with political parties. The Executive Council is usually called a cabinet and is led by a Premier, who is the leader of the majority party in parliament. The Governor exercises less power over local affairs and deals mostly with foreign affairs and economic issues, while the elected government controls most "domestic" concerns.[citation needed] |

|

Under the Gibraltar Constitution Order 2006 which was approved in Gibraltar by a referendum, Gibraltar now has a Parliament. The Government of Gibraltar, headed by the Chief Minister, is elected. Defence, external affairs and internal security vest in the Governor.[48] |

|

Bermuda, settled in 1609, and self-governed since 1620, is the oldest of the Overseas Territories. The bicameral Parliament consists of a Senate and a House of Assembly, and most executive powers have been devolved to the head of government, known as the Premier.[49] |

|

The Turks and Caicos Islands adopted a new constitution effective 9 August 2006; their head of government now also has the title Premier, their legislature is called the House of Assembly, and their autonomy has been greatly increased.[50] |

Legal system[]

Each overseas territory has its own legal system independent of the United Kingdom. The legal system is generally based on English common law, with some distinctions for local circumstances. Each territory has its own attorney general, and court system. For the smaller territories, the UK may appoint a UK-based lawyer or judge to work on legal cases. This is particularly important for cases involving serious crimes and where it is impossible to find a jury who will not know the defendant in a small population island.[51]

The Pitcairn sexual assault trial of 2004 is an example of how the UK may choose to provide the legal framework for particular cases where the territory cannot do so alone.

The highest court for all the British Overseas Territories is the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.

Police and Enforcement[]

The British Overseas Territories generally look after their own policing matters and have their own police forces. In smaller territories, the senior officer(s) may be recruited or seconded from a UK police force, and specialist staff and equipment may be sent to assist the local force.

Some territories may have other forces beyond the main territorial police, for instance an airport police, such as Airport Security Police (Bermuda), or a defence police force, such as the Gibraltar Defence Police. In addition, most territories have customs, immigration, border, and coastguard agencies.

Territories with military bases or responsibilities may also have "Overseas Service Police", members of the British or Commonwealth Armed Forces.

Joint Ministerial Council[]

British Overseas Territories Joint Ministerial Council | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | Dialogue forum |

| Seats | 28-30 |

| Elections | |

Voting system | All members elected either as MPs in the UK cabinet[clarification needed] or as heads of Government or Ministers in Overseas Territories. |

| Meeting place | |

| Westminster, London | |

| Website | |

A Joint Ministerial Council of UK ministers, and the leaders of the Overseas Territories has been held annually since 2012 to provide representation between UK Government departments and Overseas Territory Governments.[52]

Disputed sovereignty[]

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) is the subject of a territorial dispute with Mauritius, the government of which claims that the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from the rest of British Mauritius in 1965, three years before Mauritius was granted independence from the United Kingdom, was not lawful. The long-running dispute was referred in 2017 to the International Court of Justice, which issued an advisory opinion on 25 February 2019 which supported the position of the Government of Mauritius.

The British Antarctic Territory has some overlap with territorial claims by both Argentina and Chile. However, territorial claims on the continent may not currently be advanced, under the holding measures of the Antarctic Treaty System.[53]

Relations with the United Kingdom[]

Historically the Secretary of State for the Colonies and the Colonial Office were responsible for overseeing all British Colonies, but today the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has the responsibility of looking after the interests of all overseas territories except the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, which comes under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defence.[55][56] Within the FCDO, the general responsibility for the territories is handled by the Overseas Territories Directorate.[57]

In 2012, the FCO published The Overseas Territories: security, success and sustainability which set out Britain's policy for the Overseas Territories, covering six main areas:[58]

- Defence, security and safety of the territories and their people

- Successful and resilient economies

- Cherishing the environment

- Making government work better

- Vibrant and flourishing communities

- Productive links with the wider world

Britain and the overseas territories do not have diplomatic representations, although the governments of the overseas territories with indigenous populations all retain a representative office in London. The United Kingdom Overseas Territories Association (UKOTA) also represents the interests of the territories in London. The governments in both London and territories occasionally meet to mitigate or resolve disagreements over the process of governance in the territories and levels of autonomy.[59]

Britain provides financial assistance to the overseas territories via the FCDO (previously the Department for International Development). Currently[when?] only Montserrat and Saint Helena receive budgetary aid (i.e. financial contribution to recurrent funding).[citation needed] Several specialist funds are made available by the UK, including:

- The Good Government Fund which provides assistance on government administration;

- The Economic Diversification Programme Budget which aim to diversify and enhance the economic bases of the territories.

The territories have no official representation in the UK Parliament, but have informal representation through the All-Party Parliamentary Group,[60] and can petition the UK Government through the Directgov e-Petitions website.[61]

Two national parties, UKIP and the Liberal Democrats, have endorsed calls for direct representation of overseas territories in the UK Parliament, as well as backbench members of the Conservative Party and Labour Party.[62][63]

Andrew Rosindell, MP for Romford is an advocate of reserving seats in the British House of Commons for the British Overseas Territories, especially for the Falkland Islands and Gibraltar.

Foreign affairs[]

Foreign affairs of the overseas territories are handled by the FCDO in London. Some territories maintain diplomatic officers in nearby countries for trade and immigration purposes. Several of the territories in the Americas maintain membership within the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, the Caribbean Community, the Caribbean Development Bank, Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency, and the Association of Caribbean States. The territories are members of the Commonwealth of Nations through the United Kingdom. The inhabited territories compete in their own right at the Commonwealth Games, and three of the territories (Bermuda, the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands) sent teams to the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Full British citizenship[64] has been granted to most 'belongers' of overseas territories (mainly since the British Overseas Territories Act 2002).

Most countries do not recognise the sovereignty claims of any other country, including Britain's, to Antarctica and its off-shore islands. Five nations contest, with counter-claims, the UK's sovereignty in the following overseas territories:

- British Antarctic Territory – Territory overlaps Antarctic claims made by Chile and Argentina

- British Indian Ocean Territory – claimed by Mauritius

- Falkland Islands – claimed by Argentina

- Gibraltar – border disputed by Spain

- South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands – claimed by Argentina

Citizenship[]

The people of the British Overseas Territories are British Nationals. Most of the overseas territories distinguish between those British nationals who have rights reserved under the local government for those with a qualifying connection to the territory. In Bermuda, by example, this is called "Bermudian status", and can be inherited or obtained subject to conditions laid down by the local government (non-British nationals must necessarily obtain British nationality in order to obtain Bermudian status). Although the expression "belonger status" is not used in Bermuda, it is used elsewhere in Wikipedia to refer to all such statuses of various of the British Overseas Territories collectively. This status is neither a nationality nor a citizenship, though it confers rights under local legislation. Prior to 1968, the British government made no citizenship (or connected rights) distinction between its nationals in the United Kingdom and those in the British colonies (as the British Overseas Territories were then termed). Indeed, the people of Bermuda had been explicitly guaranteed by Royal Charters for the Virginia Company in 1607 (extended to Bermuda in 1612) and the Somers Isles Company (in 1615) that they and their descendants would have exactly the same rights as they would if they had they been born in England. Despite this, British Colonials without a qualifying connection to the island of Britain or Northern Ireland were stripped of the rights of abode and free entry in 1968, and in 1983 the British Government replaced Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies with British Citizenship (with rights of abode and free entry to the United Kingdom) for those with a qualifying connection to the United Kingdom or British Dependent Territories Citizenship for those with a connection only to a colony, at the same time re-designated a British Dependent Territory. This category of citizenship was distinguished from British Citizenship by what it did not include, the rights of abode and free entry to the United Kingdom, and was not specific to any colony but to all collectively, except for Gibraltar and the Falklands Islands, the people of which retained British Citizenship. It was stated by Conservative Party backbenchers that the secret intent of the Conservative Government was to restore a single citizenship with full rights across the United Kingdom and the British Dependent Territories once Hong Kong and its British Dependent Territories Citizens had been returned to the People's Republic of China in 1997. By that time, the Labour Government of Tony Blair was in government. Labour had decried the discrimination against the people of the British Dependent Territories (other than those of Gibraltar and the Falklands), which was understood universally as intended to raise a colour bar, and had done so given that most white colonials were not affected by it, and had made restoration of a single citizenship part of its election manifesto.

In 2002, when the British Dependent Territories became the British Overseas Territories, the default citizenship was renamed British Overseas Territories Citizenship (except still for Gibraltar and the Falkland Islands, for which British Citizenship remained the default), the immigration bars against its holders were lowered, and its holders were also entitled to obtain British Citizenship by obtaining a second British Passport (something that had previously been illegal) with the citizenship so indicated. As British Overseas Territories Citizens must provide their British Passport with the citizenship shown as British Overseas Territories Citizen in order to prove their entitlement to obtain a passport with the citizenship shown as British Citizen, most now have two passports, though the local governments of the territories do not distinguish an individual's local status based on either form of citizenship, and the passport with the citizenship shown as British Citizen consequently shows the holder to be entitled to all of the same right as does the passport with the citizenship shown as British Overseas Territories Citizen, and is often required to access services in the United Kingdom, and is accepted by the immigration authorities of more foreign countries, many of which have barriers against holders of British Overseas Territories Citizen passport holders that do not apply to British Citizen passport holders (the exception being the United States in relation to Bermuda, with which it has retained close links since Bermuda was founded as an extension of Virginia).

In regard to movement within British sovereign territory, only British citizenship grants the right of abode in a specific country or territory, namely, the United Kingdom proper (which includes its three Crown Dependencies). Individual overseas territories have legislative independence over immigration, and consequently, BOTC status, as noted above, does not automatically grant the right of abode in any of the territories, as it depends on the territory's immigration laws. A territory may issue belonger status to allow a person to reside in the territory that they have close links with. The governor or immigration department of a territory may also grant the territorial status to a resident who does not hold it as a birthright.

From 1949 to 1983, the nationality status of Citizenship of UK and Colonies (CUKC) was shared by residents of the UK proper and residents of overseas territories, although most residents of overseas territories lost their automatic right to live in the UK after the ratification of Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 that year unless they were born in the UK proper or had a parent or a grandparent born in the UK.[65] In 1983, CUKC status of residents of overseas territories without the right of abode in the UK was replaced by British Dependent Territories citizenship (BDTC) in the newly minted British Nationality Act 1981, a status that does not come with it the right of abode in the UK or any overseas territory. For these residents, registration as full British citizens then required physical residence in the UK proper. There were only two exceptions: Falkland Islanders, who were automatically granted British citizenship and was treated as a part of the UK proper through the enactment of British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983 due to the Falklands War with Argentina, and Gibraltarians who were given the special entitlement to be registered as British citizens upon request without further conditions because of its individual membership in the European Economic Area and the European Community.[66]

Five years after the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997, the British government amended the 1981 Act to give British citizenship without restrictions to all BDTCs (the status was also renamed BOTC at the same time) except for those solely connected with Akrotiri and Dhekelia (whose residents already held Cypriot citizenship).[67] This restored the right of abode in the UK to residents of overseas territories after a 34-year hiatus from 1968 to 2002.

Military[]

Defence of the Overseas Territories is the responsibility of the UK. Many of the overseas territories are used as military bases by the UK and its allies.

- Ascension Island (part of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha) – the Base known as RAF Ascension Island is used by both the Royal Air Force and the United States Air Force.

- Bermuda – became the primary Royal Navy base in North America, following US independence. The Naval establishment included an admiralty, a dockyard, and a naval squadron. A considerable military garrison was built up to protect it, and Bermuda, which the British Government came to see as a base, rather than as a colony, was known as Fortress Bermuda, and the Gibraltar of the West (Bermudians, like Gibraltarians, also dub their territory "The Rock").[68] Canada and the USA also established bases in Bermuda during the Second World War, which were maintained through the Cold War. Four air bases were located in Bermuda during the Second World War (operated by the Royal Air Force, Royal Navy, US Navy, and US Army/Army Air Force). Since 1995, the military force in Bermuda has been reduced to the local territorial battalion, the Royal Bermuda Regiment.

- British Indian Ocean Territory – the island of Diego Garcia is home to a large naval base and airbase leased to the United States by the United Kingdom until 2036 (unless renewed). There are British forces in small numbers in the BIOT for administrative and immigration purposes.

- Falkland Islands – the British Forces Falkland Islands includes commitments from the British Army, Royal Air Force and Royal Navy, along with the Falkland Islands Defence Force.

- Gibraltar – British Forces Gibraltar includes a Royal Navy dockyard (also used by NATO), RAF Gibraltar – used by the RAF and NATO and a local garrison – the Royal Gibraltar Regiment.

- The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus – maintained as strategic British military bases in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

- Montserrat – the Royal Montserrat Defence Force, historically connected with the Irish Guards, is a body of twenty volunteers, whose duties are primarily ceremonial.[69]

- Cayman Islands - The Cayman Regiment is the home defence unit of the Cayman Islands. It is a single territorial infantry battalion of the British Armed Forces that was formed in 2020.[70]

- Turks and Caicos - The Turks and Caicos Regiment is the home defence unit of the British Overseas Territory of the Turks and Caicos Islands. It is a single territorial infantry battalion of the British Armed Forces that was formed in 2020, similar to the Cayman Regiment.[71]

Languages[]

Most of the languages other than English spoken in the territories contain a large degree of English, either as a root language, or in codeswitching, e.g. Llanito. They include:

- Llanito or Yanito and Spanish (Gibraltar)

- Cayman Creole (Cayman Islands)

- Turks-Caicos Creole (Turks and Caicos Islands)

- Pitkern (Pitcairn Islands)

- Greek (Akrotiri and Dhekelia)

Forms of English:

- Bermudian English (Bermuda)

- Falkland Islands English

Currencies[]

The 14 British overseas territories use a varied assortment of currencies, including the Euro, British pound, United States dollar, New Zealand dollar, or their own currencies, which may be pegged to one of these.

| Location | Native currency | Issuing authority |

|---|---|---|

|

Euro |

European Central Bank |

|

Pound sterling |

Bank of England |

|

Falkland Islands pound (parity with pound sterling) |

|

|

Gibraltar pound (parity with pound sterling) |

Government of Gibraltar |

|

Saint Helenian pound (parity with pound sterling) |

Government of Saint Helena |

|

United States dollar |

US Federal Reserve |

|

Eastern Caribbean dollar (pegged to US dollar at 2.7ECD=1USD) |

Eastern Caribbean Central Bank |

|

Bermudian dollar (parity with US dollar) |

Bermuda Monetary Authority |

|

Cayman Islands dollar (pegged to US dollar at 1KYD=1.2USD) |

Cayman Islands Monetary Authority |

|

New Zealand dollar |

Reserve Bank of New Zealand |

|

United States dollar (de facto)[74][75] |

US Federal Reserve |

1 Part of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.

Symbols and insignia[]

Each overseas territory has been granted its own flag and coat of arms by the British monarch. Traditionally, the flags follow the Blue Ensign design, with the Union Flag in the canton, and the territory's coat of arms in the fly. Exceptions to this are Bermuda which uses a Red Ensign; British Antarctic Territory which uses a White Ensign, but without the overall cross of St. George; British Indian Ocean Territory which uses a Blue Ensign with wavy lines to symbolise the sea; and Gibraltar which uses a banner of its coat of arms (the flag of the city of Gibraltar).

Akrotiri and Dhekelia and Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha are the only British overseas territories without their own flag, though Saint Helena, Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha have their own individual flags. The Union Flag is used in these territories.

Sports[]

Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands are the only British Overseas Territories with recognised National Olympic Committees (NOCs); the British Olympic Association is recognised as the appropriate NOC for athletes from the other territories, and thus athletes who hold a British passport are eligible to represent Great Britain at the Olympic Games.[78]

Shara Proctor from Anguilla, Delano Williams from the Turks and Caicos Islands, Jenaya Wade-Fray from Bermuda[79] and Georgina Cassar from Gibraltar strived to represent Team GB at the London 2012 Olympics. Proctor, Wade-Fray and Cassar qualified for Team GB, with Williams missing the cut, however wishing to represent the UK in 2016.[80][81]

The Gibraltar national football team was accepted into UEFA in 2013 in time for the 2016 European Championships. It has been accepted by FIFA and went into the 2018 FIFA World Cup qualifying, where they achieved 0 points.

Gibraltar has hosted and competed in the Island Games, most recently in 2019.

Biodiversity[]

The British Overseas Territories have more biodiversity than the entire UK mainland.[82] There are at least 180 endemic plant species in the overseas territories as opposed to only 12 on the UK mainland. Responsibility for protection of biodiversity and meeting obligations under international environmental conventions is shared between the UK Government and the local governments of the territories.[83]

Two areas, Henderson Island in the Pitcairn Islands as well as the Gough and Inaccessible Islands of Tristan Da Cunha are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and two other territories, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and Saint Helena are on the United Kingdom's tentative list for future UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[84][85] Gibraltar's Gorham's Cave Complex is also found on the UK's tentative UNESCO World Heritage Site list.[86]

The three regions of biodiversity hotspots situated in the British Overseas Territories are the Caribbean Islands, the Mediterranean Basin and the Oceania ecozone in the Pacific.[83]

The UK created the largest continuous marine protected areas in the world, the Chagos Marine Protected Area, and announced in 2015 funding to establish a new, larger, reserve around the Pitcairn Islands.[87][88][89]

In January 2016, the UK government announced the intention to create a marine protected area around Ascension Island. The protected area would be 234,291 square kilometers, half of which would be closed to fishing.[90]

A Stoplight Parrotfish in Princess Alexandra Land and Sea National Park, Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands

Penguins in South Georgia, 2010

Henderson Island in the Pitcairn Islands

Rothera Research Station

See also[]

- British overseas territory citizens in the mainland United Kingdom

- Colonial Department

- Depopulation of Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago to enable building of a UK-US military base in the British Indian Ocean Territory on Diego Garcia

- List of British Army installations

- List of leaders of Overseas Territories

- List of stock exchanges in the United Kingdom, the British Crown Dependencies and United Kingdom Overseas Territories

- List of universities in British Overseas Territories

- List of postcodes in Overseas Territories

- Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Tax haven lists

- UK Overseas Territories Conservation Forum

- United Kingdom Overseas Territories Association (UKOTA)

- Overseas France

Notes[]

- ^ Excluding British Antarctic Territory.

References[]

- ^ "Supporting the Overseas Territories". UK Government. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

There are 14 Overseas Territories which retain a constitutional link with the UK. .... Most of the Territories are largely self-governing, each with its own constitution and its own government, which enacts local laws. Although the relationship is rooted in four centuries of shared history, the UK government's relationship with its Territories today is a modern one, based on mutual benefits and responsibilities. The foundations of this relationship are partnership, shared values and the right of the people of each territory to choose to freely choose whether to remain a British Overseas Territory or to seek an alternative future.

- ^ "British Overseas Territories Law". Hart Publishing. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

Most, if not all, of these territories are likely to remain British for the foreseeable future, and many have agreed modern constitutional arrangements with the British Government.

- ^ "What is the British Constitution: The Primary Structures of the British State". The Constitution Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

The United Kingdom also manages a number of territories which, while mostly having their own forms of government, have the Queen as their head of state, and rely on the UK for defence and security, foreign affairs and representation at the international level. They do not form part of the UK, but have an ambiguous constitutional relationship with the UK.

- ^ "New ministerial appointments at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office" (Press release). Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Overseas Territories". UK Overseas Territories Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Archived from the original on 5 August 2002. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "British Antarctic Territory". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Anguilla Population 2019". Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "UNdata | record view | Surface area in km2". United Nations. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Bermuda Population 2019". Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Commonwealth Secretariat – British Antarctic Territory". Thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "British Indian Ocean Territory". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Commonwealth Secretariat – British Indian Ocean Territory". Thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "British Virgin Islands (BVI)". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "British Virgin Islands (BVI)". 13 October 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Economics and Statistics Office - Labour Force Survey Report Spring 2018" (PDF). www.eso.ky. Cayman Islands Economics and Statistics Office. August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Falkland Islands Population 2019". Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Gibraltar". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Gibraltar Population 2019". Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "Montserrat". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Montserrat". 13 October 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010.

- ^ "Pitcairn Island". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Pitcairn Islands Tourism | Come Explore... The Legendary Pitcairn Islands". Visitpitcairn.pn. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Pitcairn Residents" Archived 7 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. puc.edu. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "St Helena Government". St Helena Government. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "St Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha profiles". BBC. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Archived 15 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Population of Grytviken, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands". Population.mongabay.com. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "SBA Cyprus". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Turks and Caicos Islands". Jncc.gov.uk. 1 November 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Turks and Caicos Islands Population 2019". Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee. "Global Britain and the British Overseas Territories: Resetting the relationship" (PDF). United Kingdom Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Fotbot.org". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "States of Guernsey: About Guernsey". Gov.gg. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Government – Isle of Man Public Services". Gov.im. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived 1 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Bermuda – History and Heritage". Smithsonian.com. 6 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ "Newfoundland History – Early Colonization and Settlement of Newfoundland". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Copyright 2015 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "UNC Press - In the Eye of All Trade". Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680-1783". Archived from the original on 9 January 2012.

- ^ Statute of Westminster 1931 Archived 24 December 2012 at archive.today (UK) CHAPTER 4 22 and 23 Geo 5

- ^ The Commonwealth – About Us Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Online September 2014

- ^ "Population". Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong Statistics. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ British Overseas Territories Act 2002 Archived 24 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine (text online): S. 3: "Any person who, immediately before the commencement of this section, is a British overseas territories citizen shall, on the commencement of this section, become a British citizen."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "House of Commons - Foreign Affairs - Seventh Report". publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ "Falkland Islands Legislative Assembly". Falklands.gov.fk. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 (at OPSI)". Opsi.gov.uk. 16 July 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Press Release No. 133/2007 Archived 13 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Government of Gibraltar Press Office.

- ^ "History of The Legislature". Bermuda Parliament. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Clegg, Peter (2012). "The Turks and Caicos Islands: Why Does the Cloud Still Hang?". Social and Economic Studies. 61 (1): 23–47. ISSN 0037-7651. JSTOR 41803738.

- ^ MacDowall, Fiona. "LibGuides: United Kingdom Legal Research: British External Territories". unimelb.libguides.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ "Overseas Territories Joint Ministerial Council 2015 Communique and Progress Report - Publications - GOV.UK". Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ Dodds, Klaus; Hemmings, Alan (November 2013). "Britain and the British Antarctic Territory in the wider geopolitics of the Antarctic and the Southern Ocean". International Affairs. OUP. 89 (6): 1429–1444. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12082. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Little Bay Development". Projects.dfid.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ British Overseas Territories Law, Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2011, p. 340

- ^ "Sovereign Base Areas, Background". Sovereign Base Areas, Cyprus. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "UK Overseas Territories - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "The Overseas Territories: security, success and sustainability" (PDF). Foreign & Commonwealth Office. 28 June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ British financial officials in the region for talks with dependent territories Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine – By Oscar Ramjeet, CaribbeanNetNews, (Published on Saturday, 21 March 2009)

- ^ "MP proposes British Overseas Territories be represented in Westminster – MercoPress". En.mercopress.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "HM Government e-petitions". Epetitions.direct.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Lib Dems would create an MP for Gibraltar". Gibraltar News Olive Press. 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017.

- ^ "UKIP leader defends call for Gibraltar to become part of Britain - Xinhua - English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com.

- ^ [2] Archived 5 August 2012 at archive.today Any person who, immediately before the commencement of this section, is a British overseas territories citizen shall, on the commencement of this section, become a British citizen.

- ^ "Section 1 of the 1968 Act" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Section 5 of British Nationality Act 1983

- ^ British Overseas Territories Act 2002

- ^ Bermuda[permanent dead link] at avalanchepress.com

- ^ "UK Government White Paper on Overseas Territories, June, 2012. Page 23" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Government, Cayman Islands. "Cayman Islands Regiment". www.exploregov.ky. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "TCI Regiment gets its first commanding officer". tcweeklynews.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "demtullpitcairn.com" (PDF). www.demtullpitcairn.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Asia and Pacific Review 2003/04 p.245 ISBN 1862170398

- ^ "FCO country profile". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010.

- ^ "South Asia :: British Indian Ocean Territory — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "British Indian Ocean Territory Currency". Wwp.greenwichmeantime.com. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Commemorative UK Pounds and Stamps issued in GBP have been issued. Source:[3] Archived 3 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, [4] Archived 27 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Overseas Territories Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee.

- ^ Stephen Wright (28 July 2012). "Representing Britain...and Bermuda | Bermuda Olympics 2012". Royalgazette.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Williams' Olympic hopes on hold for 4 more years". Fptci.com. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Purnell, Gareth (27 July 2012). "At last! Phillips Idowu tracked down... in Team GB photo – Olympic News". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "About the Biodiversity of the UK Overseas Territories". UKOTCF. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Science: UK Overseas Territories: Biodiversity". Kew. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Turks and Caicos Islands – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Island of St Helena – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Gorham's Cave Complex". UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "World's Largest Single Marine Reserve Created in Pacific". National Geographic. World's Largest Single Marine Reserve Created in Pacific. 18 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Pitcairn Islands get huge marine reserve". BBC. 18 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Pitcairn Islands to get world's largest single marine reserve". The Guardian. London. 18 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Ascension Island to become marine reserve". 3 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

Further reading[]

- Charles Cawley. Colonies in Conflict: The History of the British Overseas Territories (2015) 444pp

- Harry Ritchie, The Last Pink Bits: Travels Through the Remnants of the British Empire (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1997)

- Simon Winchester, Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire (London & New York, 1985)

- George Drower, Britain's Dependent Territories (Dartmouth, 1992)

- George Drower, Overseas Territories Handbook (London: TSO, 1998)

- Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson, "British Overseas Territories Law" (London: Hart Publishing, 2011)

- Ben Fogle, The Teatime Islands: Adventures in Britain's Faraway Outposts (London: Michael Joseph, 2003)

- Bonham C. Richardson (16 January 1992). The Caribbean in the Wider World, 1492–1992. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521359771. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British Overseas Territories. |

- British Overseas Territories

- British colonization of the Americas

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Dependent territories of European countries

- Governance of the British Empire

- History of the British Empire

- History of the Commonwealth of Nations

- 1983 establishments in British Overseas Territories