CD40 (protein)

Cluster of differentiation 40, CD40 is a costimulatory protein found on antigen-presenting cells and is required for their activation. The binding of CD154 (CD40L) on TH cells to CD40 activates antigen presenting cells and induces a variety of downstream effects.

Deficiency can cause Hyper-IgM syndrome type 3.

Function[]

The protein receptor encoded by this gene is a member of the TNF-receptor superfamily. This receptor has been found to be essential in mediating a broad variety of immune and inflammatory responses including T cell-dependent immunoglobulin class switching, memory B cell development, and germinal center formation.[5] AT-hook transcription factor AKNA is reported to coordinately regulate the expression of this receptor and its ligand, which may be important for homotypic cell interactions. The interaction of this receptor and its ligand is found to be necessary for amyloid-beta-induced microglial activation, and thus is thought to be an early event in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Two alternatively spliced transcript variants of this gene encoding distinct isoforms have been reported.[6]

Specific effects on cells[]

In the macrophage, the primary signal for activation is IFN-γ from Th1 type CD4 T cells. The secondary signal is CD40L (CD154) on the Th1 cell which binds CD40 on the macrophage cell surface. As a result, the macrophage expresses more CD40 and TNF receptors on its surface which helps increase the level of activation. The increase in activation results in the induction of potent microbicidal substances in the macrophage, including reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide, leading to the destruction of ingested microbe.

The B cell can present antigens to helper T cells. If an activated T cell recognizes the peptide presented by the B cell, the CD40L on the T cell binds to the B cell's CD40 receptor, causing B cell activation. The T cell also produces IL-2, which directly influences B cells. As a result of this net stimulation, the B cell can undergo division, antibody isotype switching, and differentiation to plasma cells. The end-result is a B cell that is able to mass-produce specific antibodies against an antigenic target. Early evidence for these effects were that in CD40 or CD154 deficient mice, there is little class switching or germinal centre formation,[7] and immune responses are severely inhibited.

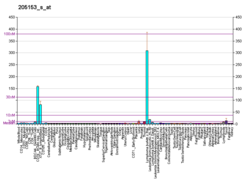

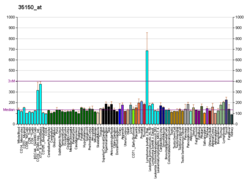

The expression of CD40 is diverse. CD40 is constitutively expressed by antigen presenting cells, including dendritic cells, B cells and macrophages. It can also be expressed by endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and epithelial cells.[8] Consistent with its widespread expression on normal cells, CD40 is also expressed on a wide range of tumor cells, including non-Hodgkin's and Hodgkin's lymphomas, myeloma and some carcinomas including nasopharynx, bladder, cervix, kidney and ovary. CD40 is also expressed on B cell precursors in the bone marrow, and there is some evidence that CD40-CD154 interactions may play a role in the control of B cell haematopoiesis.[9]

Interactions[]

CD40 (protein) has been shown to interact with TRAF2,[10][11][12] TRAF3,[11][13][14][15] TRAF6,[11][15] TRAF5[11][16] and TTRAP.[17] The remaining member of TRAF4 family, namely TRAF4, positively regulates CD40 signalling, but interacts with CD40 indirectly.[18]

CD40 as a drug target in cancer[]

CD40 molecule is a potential target for cancer immunotherapy. There are number of completed and ongoing clinical trials where agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies are employed to activate an anti-tumor T cell response via activation of dendritic cells.[19]

References[]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000101017 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000017652 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Grewal IS, Flavell RA (1998). "CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 16: 111–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. PMID 9597126.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: CD40 CD40 molecule, TNF receptor superfamily member 5".

- ^ Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, Tanaka T, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H (June 1994). "The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation". Immunity. 1 (3): 167–78. doi:10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. PMID 7534202.

- ^ Chatzigeorgiou A, Lyberi M, Chatzilymperis G, Nezos A, Kamper E (2009). "CD40/CD40L signaling and its implication in health and disease". BioFactors. 35 (6): 474–83. doi:10.1002/biof.62. PMID 19904719. S2CID 22911861.

- ^ Carlring J, Altaher HM, Clark S, Chen X, Latimer SL, Jenner T, Buckle AM, Heath AW (May 2011). "CD154-CD40 interactions in the control of murine B cell hematopoiesis". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 89 (5): 697–706. doi:10.1189/jlb.0310179. PMC 3382295. PMID 21330346.

- ^ McWhirter SM, Pullen SS, Holton JM, Crute JJ, Kehry MR, Alber T (July 1999). "Crystallographic analysis of CD40 recognition and signaling by human TRAF2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (15): 8408–13. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.8408M. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.15.8408. PMC 17529. PMID 10411888.

- ^ a b c d Tsukamoto N, Kobayashi N, Azuma S, Yamamoto T, Inoue J (February 1999). "Two differently regulated nuclear factor kappaB activation pathways triggered by the cytoplasmic tail of CD40". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (4): 1234–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.1234T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.4.1234. PMC 15446. PMID 9990007.

- ^ Malinin NL, Boldin MP, Kovalenko AV, Wallach D (February 1997). "MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-kappaB induction by TNF, CD95 and IL-1". Nature. 385 (6616): 540–4. doi:10.1038/385540a0. PMID 9020361. S2CID 4366355.

- ^ Hu HM, O'Rourke K, Boguski MS, Dixit VM (December 1994). "A novel RING finger protein interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of CD40". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (48): 30069–72. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43772-6. PMID 7527023.

- ^ Ni CZ, Welsh K, Leo E, Chiou CK, Wu H, Reed JC, Ely KR (September 2000). "Molecular basis for CD40 signaling mediated by TRAF3". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (19): 10395–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710395N. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.19.10395. PMC 27035. PMID 10984535.

- ^ a b Roy N, Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC (December 1997). "The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases". The EMBO Journal. 16 (23): 6914–25. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. PMC 1170295. PMID 9384571.

- ^ Ishida TK, Tojo T, Aoki T, Kobayashi N, Ohishi T, Watanabe T, Yamamoto T, Inoue J (September 1996). "TRAF5, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor family protein, mediates CD40 signaling". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (18): 9437–42. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.9437I. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9437. PMC 38446. PMID 8790348.

- ^ Pype S, Declercq W, Ibrahimi A, Michiels C, Van Rietschoten JG, Dewulf N, de Boer M, Vandenabeele P, Huylebroeck D, Remacle JE (June 2000). "TTRAP, a novel protein that associates with CD40, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-75 and TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), and that inhibits nuclear factor-kappa B activation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (24): 18586–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M000531200. PMID 10764746.

- ^ Sharma S, Pavlasova GM, Seda V, Cerna KA, Vojackova E, Filip D, Ondrisova L, Sandova V, Kostalova L, Zeni PF, Borsky M, Oppelt J, Liskova K, Kren L, Janikova A, Pospisilova S, Fernandes SM, Shehata M, Rassenti LZ, Jaeger U, Doubek M, Davids MS, Brown JR, Mayer J, Kipps TJ, Mraz M (December 2020). "miR-29 Modulates CD40 Signaling in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia by Targeting TRAF4: an Axis Affected by BCR inhibitors". Blood. 137 (18): 2481–2494. doi:10.1182/blood.2020005627. PMC 7610744. PMID 33171493.

- ^ Vonderheide RH (April 2018). "The Immune Revolution: A Case for Priming, Not Checkpoint". Cancer Cell. 33 (4): 563–569. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.008. PMC 5898647. PMID 29634944.

External links[]

- Human CD40 genome location and CD40 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 5 (CD40)

Further reading[]

- Parham P (2004). The Immune System (2nd ed.). Garland Science. pp. 169–173. ISBN 978-0-8153-4093-5.

- Wang JH, Zhang YW, Zhang P, Deng BQ, Ding S, Wang ZK, Wu T, Wang J (September 2013). "CD40 ligand as a potential biomarker for atherosclerotic instability". Neurological Research. 35 (7): 693–700. doi:10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000190. PMC 3770830. PMID 23561892.

- Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Brière F, Galizzi JP, van Kooten C, Liu YJ, Rousset F, Saeland S (1994). "The CD40 antigen and its ligand". Annual Review of Immunology. 12: 881–922. doi:10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. PMID 7516669.

- van Kooten C, Banchereau J (January 2000). "CD40-CD40 ligand". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 67 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. PMID 10647992. S2CID 35592719.

- Schattner EJ (May 2000). "CD40 ligand in CLL pathogenesis and therapy". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 37 (5–6): 461–72. doi:10.3109/10428190009058499. PMID 11042507. S2CID 39398949.

- Bhushan A, Covey LR (2002). "CD40:CD40L interactions in X-linked and non-X-linked hyper-IgM syndromes". Immunologic Research. 24 (3): 311–24. doi:10.1385/IR:24:3:311. PMID 11817328. S2CID 19537892.

- Cheng G, Schoenberger SP (2002). "CD40 signaling and autoimmunity". Signal Transduction Pathways in Autoimmunity. Current Directions in Autoimmunity. Vol. 5. pp. 51–61. doi:10.1159/000060547. ISBN 978-3-8055-7308-5. PMID 11826760.

- Dallman C, Johnson PW, Packham G (January 2003). "Differential regulation of cell survival by CD40". Apoptosis. 8 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1023/A:1021696902187. PMID 12510151. S2CID 22461134.

- O'Sullivan B, Thomas R (July 2003). "Recent advances on the role of CD40 and dendritic cells in immunity and tolerance". Current Opinion in Hematology. 10 (4): 272–8. doi:10.1097/00062752-200307000-00004. PMID 12799532. S2CID 43043879.

- Benveniste EN, Nguyen VT, Wesemann DR (January 2004). "Molecular regulation of CD40 gene expression in macrophages and microglia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 18 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.001. PMID 14651941. S2CID 8081107.

- Xu Y, Song G (2005). "The role of CD40-CD154 interaction in cell immunoregulation". Journal of Biomedical Science. 11 (4): 426–38. doi:10.1159/000077892. PMID 15153777. S2CID 202658036.

- Contin C, Couzi L, Moreau JF, Déchanet-Merville J, Merville P (2004). "[Immune dysfuntion of uremic patients: potential role for the soluble form of CD40]". Nephrologie. 25 (4): 119–26. PMID 15291139.

- Genes on human chromosome 20

- Clusters of differentiation