Chatbot

A chatbot is a software application used to conduct an on-line chat conversation via text or text-to-speech, in lieu of providing direct contact with a live human agent.[1] Designed to convincingly simulate the way a human would behave as a conversational partner, chatbot systems typically require continuous tuning and testing, and many in production remain unable to adequately converse or pass the industry standard Turing test.[2] The term "ChatterBot" was originally coined by Michael Mauldin (creator of the first Verbot) in 1994 to describe these conversational programs.[3]

Chatbots are used in dialog systems for various purposes including customer service, request routing, or information gathering. While some chatbot applications use extensive word-classification processes, natural language processors, and sophisticated AI, others simply scan for general keywords and generate responses using common phrases obtained from an associated library or database.

Most chatbots are accessed on-line via website popups or through virtual assistants. They can be classified into usage categories that include: commerce (e-commerce via chat), education, entertainment, finance, health, news, and productivity.[4]

Background[]

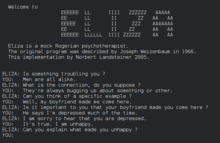

In 1950, Alan Turing's famous article "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" was published,[5] which proposed what is now called the Turing test as a criterion of intelligence. This criterion depends on the ability of a computer program to impersonate a human in a real-time written conversation with a human judge to the extent that the judge is unable to distinguish reliably—on the basis of the conversational content alone—between the program and a real human. The notoriety of Turing's proposed test stimulated great interest in Joseph Weizenbaum's program ELIZA, published in 1966, which seemed to be able to fool users into believing that they were conversing with a real human. However Weizenbaum himself did not claim that ELIZA was genuinely intelligent, and the introduction to his paper presented it more as a debunking exercise:

[In] artificial intelligence ... machines are made to behave in wondrous ways, often sufficient to dazzle even the most experienced observer. But once a particular program is unmasked, once its inner workings are explained ... its magic crumbles away; it stands revealed as a mere collection of procedures ... The observer says to himself "I could have written that". With that thought, he moves the program in question from the shelf marked "intelligent", to that reserved for curios ... The object of this paper is to cause just such a re-evaluation of the program about to be "explained". Few programs ever needed it more.[6]

ELIZA's key method of operation (copied by chatbot designers ever since) involves the recognition of clue words or phrases in the input, and the output of the corresponding pre-prepared or pre-programmed responses that can move the conversation forward in an apparently meaningful way (e.g. by responding to any input that contains the word 'MOTHER' with 'TELL ME MORE ABOUT YOUR FAMILY').[7] Thus an illusion of understanding is generated, even though the processing involved has been merely superficial. ELIZA showed that such an illusion is surprisingly easy to generate because human judges are so ready to give the benefit of the doubt when conversational responses are capable of being interpreted as "intelligent".

Interface designers have come to appreciate that humans' readiness to interpret computer output as genuinely conversational—even when it is actually based on rather simple pattern-matching—can be exploited for useful purposes. Most people prefer to engage with programs that are human-like, and this gives chatbot-style techniques a potentially useful role in interactive systems that need to elicit information from users, as long as that information is relatively straightforward and falls into predictable categories. Thus, for example, online help systems can usefully employ chatbot techniques to identify the area of help that users require, potentially providing a "friendlier" interface than a more formal search or menu system. This sort of usage holds the prospect of moving chatbot technology from Weizenbaum's "shelf ... reserved for curios" to that marked "genuinely useful computational methods".

Development[]

Among the most notable early chatbots are ELIZA (1966) and PARRY (1972).[8][9][10][11] More recent notable programs include A.L.I.C.E., Jabberwacky and D.U.D.E (Agence Nationale de la Recherche and CNRS 2006). While ELIZA and PARRY were used exclusively to simulate typed conversation, many chatbots now include other functional features, such as games and web searching abilities. In 1984, a book called The Policeman's Beard is Half Constructed was published, allegedly written by the chatbot Racter (though the program as released would not have been capable of doing so).[12]

One pertinent field of AI research is natural language processing. Usually, weak AI fields employ specialized software or programming languages created specifically for the narrow function required. For example, A.L.I.C.E. uses a markup language called AIML, which is specific to its function as a conversational agent, and has since been adopted by various other developers of, so-called, Alicebots. Nevertheless, A.L.I.C.E. is still purely based on pattern matching techniques without any reasoning capabilities, the same technique ELIZA was using back in 1966. This is not strong AI, which would require sapience and logical reasoning abilities.

Jabberwacky learns new responses and context based on real-time user interactions, rather than being driven from a static database. Some more recent chatbots also combine real-time learning with evolutionary algorithms that optimize their ability to communicate based on each conversation held. Still, there is currently no general purpose conversational artificial intelligence, and some software developers focus on the practical aspect, information retrieval.

Chatbot competitions focus on the Turing test or more specific goals. Two such annual contests are the Loebner Prize and The Chatterbox Challenge (the latter has been offline since 2015, however, materials can still be found from web archives).[13]

DBpedia created a chatbot during the GSoC of 2017.[14][15][16] It can communicate through Facebook Messenger.

Application[]

Messaging apps[]

Many companies' chatbots run on messaging apps or simply via SMS. They are used for B2C customer service, sales and marketing.[17]

In 2016, Facebook Messenger allowed developers to place chatbots on their platform. There were 30,000 bots created for Messenger in the first six months, rising to 100,000 by September 2017.[18]

Since September 2017, this has also been as part of a pilot program on WhatsApp. Airlines KLM and Aeroméxico both announced their participation in the testing;[19][20][21][22] both airlines had previously launched customer services on the Facebook Messenger platform.

The bots usually appear as one of the user's contacts, but can sometimes act as participants in a group chat.

Many banks, insurers, media companies, e-commerce companies, airlines, hotel chains, retailers, health care providers, government entities and restaurant chains have used chatbots to answer simple questions, increase customer engagement,[23] for promotion, and to offer additional ways to order from them.[24][25]

A 2017 study showed 4% of companies used chatbots.[26] According to a 2016 study, 80% of businesses said they intended to have one by 2020.[27]

As part of company apps and websites[]

Previous generations of chatbots were present on company websites, e.g. Ask Jenn from Alaska Airlines which debuted in 2008[28] or Expedia's virtual customer service agent which launched in 2011.[28][29] The newer generation of chatbots includes IBM Watson-powered "Rocky", introduced in February 2017 by the New York City-based e-commerce company Rare Carat to provide information to prospective diamond buyers.[30][31]

Chatbot sequences[]

Used by marketers to script sequences of messages, very similar to an Autoresponder sequence. Such sequences can be triggered by user opt-in or the use of keywords within user interactions. After a trigger occurs a sequence of messages is delivered until the next anticipated user response. Each user response is used in the decision tree to help the chatbot navigate the response sequences to deliver the correct response message.

Company internal platforms[]

Other companies explore ways they can use chatbots internally, for example for Customer Support, Human Resources, or even in Internet-of-Things (IoT) projects. Overstock.com, for one, has reportedly launched a chatbot named Mila to automate certain simple yet time-consuming processes when requesting sick leave.[32] Other large companies such as Lloyds Banking Group, Royal Bank of Scotland, Renault and Citroën are now using automated online assistants instead of call centres with humans to provide a first point of contact. A SaaS chatbot business ecosystem has been steadily growing since the F8 Conference when Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg unveiled that Messenger would allow chatbots into the app.[33] In large companies, like in hospitals and aviation organizations, IT architects are designing reference architectures for Intelligent Chatbots that are used to unlock and share knowledge and experience in the organization more efficiently, and reduce the errors in answers from expert service desks significantly.[34] These Intelligent Chatbots make use of all kinds of artificial intelligence like image moderation and natural language understanding (NLU), natural language generation (NLG), machine learning and deep learning.

Customer Service[]

Many high-tech banking organizations are looking to integrate automated AI-based solutions such as chatbots into their customer service in order to provide faster and cheaper assistance to their clients who are becoming increasingly comfortable with technology. In particular, chatbots can efficiently conduct a dialogue, usually replacing other communication tools such as email, phone, or SMS. In banking, their major application is related to quick customer service answering common requests, as well as transactional support.

Several studies report significant reduction in the cost of customer services, expected to lead to billions of dollars of economic savings in the next ten years.[35] In 2019, Gartner predicted that by 2021, 15% of all customer service interactions globally will be handled completely by AI.[36] A study by Juniper Research in 2019 estimates retail sales resulting from chatbot-based interactions will reach $112 billion by 2023.[37]

Since 2016, when Facebook allowed businesses to deliver automated customer support, e-commerce guidance, content, and interactive experiences through chatbots, a large variety of chatbots were developed for the Facebook Messenger platform.[38]

In 2016, Russia-based Tochka Bank launched the world's first Facebook bot for a range of financial services, including a possibility of making payments.[39]

In July 2016, Barclays Africa also launched a Facebook chatbot, making it the first bank to do so in Africa.[40]

The France's third-largest bank by total assets[41] Société Générale launched their chatbot called SoBot in March 2018. While 80% of users of the SoBot expressed their satisfaction after having tested it, Société Générale deputy director Bertrand Cozzarolo stated that it will never replace the expertise provided by a human advisor. [42]

The advantages of using chatbots for customer interactions in banking include cost reduction, financial advice, and 24/7 support.[43][44]

Healthcare[]

Chatbots are also appearing in the healthcare industry.[45][46] A study suggested that physicians in the United States believed that chatbots would be most beneficial for scheduling doctor appointments, locating health clinics, or providing medication information.[47]

Whatsapp has tied up with the World Health Organisation (WHO) to make a chatbot service that answers users’ questions on Covid-19.[48]

The Indian Government recently launched a chatbot called MyGov Corona Helpdesk,[49] that works through Whatsapp and helps people access information about the Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.[50][51]

Certain patient groups are still reluctant to use chatbots. A mixed-methods study showed that people are still hesitant to use chatbots for their healthcare due to poor understanding of the technological complexity, the lack of empathy, and concerns about cyber-security.[52] The analysis showed that while 6% had heard of a health chatbot and 3% had experience of using it, 67% perceived themselves as likely to use one within 12 months. The majority of participants would use a health chatbot for seeking general health information (78%), booking a medical appointment (78%), and looking for local health services (80%). However, a health chatbot was perceived as less suitable for seeking results of medical tests and seeking specialist advice such as sexual health. The analysis of attitudinal variables showed that most participants reported their preference for discussing their health with doctors (73%) and having access to reliable and accurate health information (93%). While 80% were curious about new technologies that could improve their health, 66% reported only seeking a doctor when experiencing a health problem and 65% thought that a chatbot was a good idea. Interestingly, 30% reported dislike about talking to computers, 41% felt it would be strange to discuss health matters with a chatbot and about half were unsure if they could trust the advice given by a chatbot. Therefore, perceived trustworthiness, individual attitudes towards bots, and dislike for talking to computers are the main barriers to health chatbots.

Politics[]

In New Zealand, the chatbot SAM – short for Semantic Analysis Machine[53] (made by Nick Gerritsen of Touchtech[54]) – has been developed. It is designed to share its political thoughts, for example on topics such as climate change, healthcare and education, etc. It talks to people through Facebook Messenger.[55][56][57][58]

In India, the state government has launched a chatbot for its Aaple Sarkar platform,[59] which provides conversational access to information regarding public services managed.[60][61]

Toys[]

Chatbots have also been incorporated into devices not primarily meant for computing, such as toys.[62]

Hello Barbie is an Internet-connected version of the doll that uses a chatbot provided by the company ToyTalk,[63] which previously used the chatbot for a range of smartphone-based characters for children.[64] These characters' behaviors are constrained by a set of rules that in effect emulate a particular character and produce a storyline.[65]

The My Friend Cayla doll was marketed as a line of 18-inch (46 cm) dolls which uses speech recognition technology in conjunction with an Android or iOS mobile app to recognize the child's speech and have a conversation. It, like the Hello Barbie doll, attracted controversy due to vulnerabilities with the doll's Bluetooth stack and its use of data collected from the child's speech.

IBM's Watson computer has been used as the basis for chatbot-based educational toys for companies such as CogniToys[62] intended to interact with children for educational purposes.[66]

Malicious use[]

Malicious chatbots are frequently used to fill chat rooms with spam and advertisements, by mimicking human behavior and conversations or to entice people into revealing personal information, such as bank account numbers. They were commonly found on Yahoo! Messenger, Windows Live Messenger, AOL Instant Messenger and other instant messaging protocols. There has also been a published report of a chatbot used in a fake personal ad on a dating service's website.[67]

Tay, an AI chatbot that learns from previous interaction, caused major controversy due to it being targeted by internet trolls on Twitter. The bot was exploited, and after 16 hours began to send extremely offensive Tweets to users. This suggests that although the bot learned effectively from experience, adequate protection was not put in place to prevent misuse.[68]

If a text-sending algorithm can pass itself off as a human instead of a chatbot, its message would be more credible. Therefore, human-seeming chatbots with well-crafted online identities could start scattering fake news that seems plausible, for instance making false claims during a presidential election. With enough chatbots, it might be even possible to achieve artificial social proof.[69][70]

Limitations of chatbots[]

The creation and implementation of chatbots is still a developing area, heavily related to artificial intelligence and machine learning, so the provided solutions, while possessing obvious advantages, have some important limitations in terms of functionalities and use cases. However, this is changing over time.

The most common limitations are listed below:[71]

- As the database, used for output generation, is fixed and limited, chatbots can fail while dealing with an unsaved query.[44]

- A chatbot's efficiency highly depends on language processing and is limited because of irregularities, such as accents and mistakes.

- Chatbots are unable to deal with multiple questions at the same time and so conversation opportunities are limited.[71]

- Chatbots require a large amount of conversational data to train.

- Chatbots have difficulty managing non-linear conversations that must go back and forth on a topic with a user [72]

- As it happens usually with technology-led changes in existing services, some consumers, more often than not from the old generation, are uncomfortable with chatbots due to their limited understanding, making it obvious that their requests are being dealt with by machines.[71]

Chatbots and jobs[]

Chatbots are increasingly present in businesses and often are used to automate tasks that do not require skill-based talents. With customer service taking place via messaging apps as well as phone calls, there are growing numbers of use-cases where chatbot deployment gives organizations a clear return on investment. Call center workers may be particularly at risk from AI-driven chatbots.[73]

A study by Forrester (June 2017) predicted that 25% of all jobs would be impacted by AI technologies by 2019.[74]

See also[]

- Applications of artificial intelligence

- Eugene Goostman

- Interactive online characters

- Internet bot

- List of chatbots

- Social bot

- Software bot

- Twitterbot

- Virtual assistant

References[]

- ^ "What is a chatbot?". techtarget.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Luka Bradeško, Dunja Mladenić. "A Survey of Chabot Systems through a Loebner Prize Competition". S2CID 39745939. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Mauldin 1994

- ^ "2017 Messenger Bot Landscape, a Public Spreadsheet Gathering 1000+ Messenger Bots". 3 May 2017.

- ^ (Turing 1950)

- ^ (Weizenbaum 1966, p. 36)

- ^ (Weizenbaum 1966, pp. 44–5)

- ^ GüzeldereFranchi 1995

- ^ Computer History Museum 2006

- ^ Sondheim 1997

- ^ Network Working Group 1973—Transcript of a session between Parry and Eliza. (This is not the dialogue from the ICCC, which took place October 24–26, 1972, whereas this session is from September 18, 1972.)

- ^ www.everything.com 13 November 1999

- ^ "Chatroboter simulieren Menschen".

- ^ "DBpedia Chatbot". chat.dbpedia.org.

- ^ "Meet the DBpedia Chatbot | DBpedia". wiki.dbpedia.org.

- ^ "Meet the DBpedia Chatbot". August 22, 2018.

- ^ Beaver, Laurie (July 2016). The Chatbots Explainer. BI Intelligence.

- ^ "Facebook Messenger Hits 100,000 bots". 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ^ "KLM claims airline first with WhatsApp Business Platform".

- ^ Staff, Forbes (26 October 2017). "Aeroméxico te atenderá por WhatsApp durante 2018". Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Redacción (27 October 2017). "Podrás hacer 'check in' y consultar tu vuelo con Aeroméxico a través de WhatsApp". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "Building for People, and Now Businesses". WhatsApp.com. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "She is the company's most effective employee". Nordea News.

- ^ "Better believe the bot boom is blowing up big for B2B, B2C businesses". VentureBeat. 2016-07-24.

- ^ "Chatbots Take Education To the Next Level – Chatbot News Daily". Chatbot News Daily. 2016-09-29. Retrieved 2017-06-23.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The AI Revolution is Underway! – PM360". www.pm360online.com. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "80% of businesses want chatbots by 2020". Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Virtual Travel Agent With All the Answers". The New York Times. 4 March 2008.

- ^ "Chatbot vendor directory released –". www.hypergridbusiness.com.

- ^ "Rare Carat's Watson-powered chatbot will help you put a diamond ring on it". TechCrunch. February 15, 2017.

- ^ "10 ways you may have already used IBM Watson". VentureBeat. March 10, 2017.

- ^ Greenfield, Rebecca. "Chatbots Are Your Newest, Dumbest Co-Workers". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Facebook opens its Messenger platform to chatbots". 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Chatbot Reference Architecture". 1 January 2019.

- ^ "How Chatbots are Transforming Wall Street and Main Street Banks?". 1 April 2019.

- ^ "How to Manage Customer Service Technology Innovation". www.gartner.com. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ "CHATBOT INTERACTIONS IN RETAIL TO REACH 22 BILLION BY 2023, AS AI OFFERS COMPELLING NEW ENGAGEMENT SOLUTIONS". www.juniperresearch.com. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ "Facebook launches Messenger platform with chatbots". 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Российский банк запустил чат-бота в Facebook". 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Absa launches 'world-first' Facebook Messenger banking". 1 April 2019.

- ^ "The Biggest French Banks by Total Assets". Banks around the World. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ "GAGNER DU TEMPS AVEC LE CHATBOT BANCAIRE POUR GAGNER EN INTELLIGENCE AVEC LES CONSEILLERS". Marketing Client. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ "Meet 11 of the Most Interesting Chatbots in Banking". The Financial Brain. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "CHATBOTS: BOON OR BANE?". bluelupin. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ Larson, Selena (October 11, 2016). "Baidu is bringing AI chatbots to healthcare". CNN Money.

- ^ "AI chatbots have a future in healthcare, with caveats". AI in Healthcare.

- ^ Palanica, Adam; Flaschner, Peter; Thommandram, Anirudh; Li, Michael; Fossat, Yan (January 3, 2019). "Physicians' Perceptions of Chatbots in Health Care: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 21 (4): e12887. doi:10.2196/12887. PMC 6473203. PMID 30950796.

- ^ Ahaskar, Abhijit (2020-03-27). "How WhatsApp chatbots are helping in the fight against Covid-19". Mint (newspaper). Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "India's Coronavirus Chatbot on WhatsApp Crosses 1.7 Crore Users in 10 Days". NDTV Gadgets 360. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Kurup, Rajesh. "COVID-19: Govt of India launches a WhatsApp chatbot". Business Line. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "In focus: Mumbai-based Haptik which developed India's official WhatsApp chatbot for Covid-19". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Nadarzynski, Tom; Miles, Oliver; Cowie, Aimee; Ridge, Damien (January 1, 2019). "Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: A mixed-methods study". Digital Health. 5: 2055207619871808. doi:10.1177/2055207619871808. PMC 6704417. PMID 31467682.

- ^ "Sam, the virtual politician". Tuia Innovation.

- ^ Wellington, Victoria University of (December 15, 2017). "Meet the world's first virtual politician". Victoria University of Wellington.

- ^ Wagner, Meg. "This virtual politician wants to run for office". CNN.

- ^ "Talk with the first-ever robot politician on Facebook Messenger". Engadget.

- ^ Prakash, Abishur (August 8, 2018). "AI-Politicians: A Revolution In Politics". Medium.

- ^ SAM website

- ^ "Maharashtra government launches Aaple Sarkar chatbot to provide info on 1,400 public services". CNBC TV18. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Government of Maharashtra launches Aaple Sarkar chatbot with Haptik". The Economic Times. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Aggarwal, Varun. "Maharashtra launches Aaple Sarkar chatbot". Business Line. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amy (2015-02-23). "Conversational Toys – The Latest Trend in Speech Technology". Virtual Agent Chat. Archived from the original on 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ^ NAGY, EVIE. "USING TOY-TALK TECHNOLOGY, NEW HELLO BARBIE WILL HAVE REAL CONVERSATIONS WITH KIDS". Fast Company. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Oren Jacob, the co-founder and CEO of ToyTalk interviewed on the TV show Triangulation on the TWiT.tv network

- ^ "Artificial intelligence script tool".

- ^ Takahashi, Dean. "Elemental's smart connected toy taps IBM's Watson supercomputer for its brains". Venture Beat. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "From Russia With Love" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-09. Psychologist and Scientific American: Mind contributing editor Robert Epstein reports how he was initially fooled by a chatterbot posing as an attractive girl in a personal ad he answered on a dating website. In the ad, the girl portrayed herself as being in Southern California and then soon revealed, in poor English, that she was actually in Russia. He became suspicious after a couple of months of email exchanges, sent her an email test of gibberish, and she still replied in general terms. The dating website is not named. Scientific American: Mind, October–November 2007, page 16–17, "From Russia With Love: How I got fooled (and somewhat humiliated) by a computer". Also available online.

- ^ Bird, Jordan J.; Ekart, Aniko; Faria, Diego R. (June 2018). Learning from Interaction: An Intelligent Networked-based Human-bot and Bot-bot Chatbot System in: Advances in Computational Intelligence Systems (1st ed.). Nottingham, UK: Springer. pp. 179–190. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-97982-3_15. ISBN 978-3-319-97982-3.

- ^ "Fake News". Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ "Malicious uses". Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Meet 11 of the Most Interesting Chatbots in Banking". Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Grudin, Jonathan; Jacques, Richard (2019), "Chatbots, Humbots, and the Quest for Artificial General Intelligence", Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI '19, ACM CHI 2020, pp. 209–219, doi:10.1145/3290605.3300439, ISBN 978-1-4503-5970-2, S2CID 140274744

- ^ "How talking machines are taking call center jobs". Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ "How chatbots are killing jobs (and creating new ones)". June 2017. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

Bibliography[]

- Computer History Museum (2006), "Internet History—1970's", Exhibits, Computer History Museum, archived from the original on 2008-02-21, retrieved 2008-03-05

- Güzeldere, Güven; Franchi, Stefano (1995-07-24), "Constructions of the Mind", Stanford Humanities Review, SEHR, Stanford University, 4 (2), retrieved 2008-03-05

- Mauldin, Michael (1994), "ChatterBots, TinyMuds, and the Turing Test: Entering the Loebner Prize Competition", Proceedings of the Eleventh National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI Press, retrieved 2008-03-05 (abstract)

- Network Working Group (1973), "RFC 439, PARRY Encounters the DOCTOR", Internet Engineering Task Force, Internet Society, retrieved 2008-03-05

- Sondheim, Alan J (1997), <nettime> Important Documents from the Early Internet (1972), nettime.org, archived from the original on 2008-06-13, retrieved 2008-03-05

- Turing, Alan (1950), "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind, 59 (236): 433–60, doi:10.1093/mind/lix.236.433

- Weizenbaum, Joseph (January 1966), "ELIZA—A Computer Program For the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man And Machine", Communications of the ACM, 9 (1): 36–45, doi:10.1145/365153.365168, S2CID 1896290

Further reading[]

- Searle, John (1980), "Minds, Brains and Programs", Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3): 417–457, doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756

- Shevat, Amir (2017). Designing bots: Creating conversational experiences (First ed.). Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4919-7482-7. OCLC 962125282.

- Chatbots

- Instant messaging

- Interactive narrative

- Natural language parsing