Climate change in New Zealand

Climate change in New Zealand is changes in the climate of New Zealand in relation to global climate change.[2][3] In 2014, New Zealand contributed 0.17% to the world's total greenhouse gas emissions.[needs update] However, on a per capita basis, New Zealand is a significant emitter – the 21st highest contributor in the world and fifth highest within the OECD.[4]

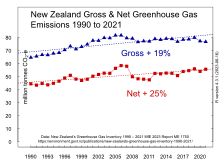

New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions are on the increase. Between 1990 and 2017, New Zealand's gross emissions (excluding removals from land use and forestry) increased by 23.1%.[needs update] When the uptake of carbon dioxide by forests (sequestration) is taken into account, net emissions (including removals from land use and forestry) have also risen – by 64.9% since 1990.[5][6][needs update]

Climate change is being responded to in a variety of ways by civil society and the government of New Zealand. This includes participation in international treaties and in social and political debates related to climate change. New Zealand has an emissions trading scheme and from 1 July 2010, the energy and liquid fossil fuel and some industry sectors have obligations to report emissions and to obtain and surrender emissions units (carbon credits). In May 2019, in response to commitments made in Paris in 2016, the Government introduced the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Bill which created a Climate Change Commission responsible for advising government led policies.[7][8]

Greenhouse gas emissions[]

By type of greenhouse gas[]

This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

New Zealand has a relatively unique emissions profile. In 2017, agriculture contributed 48% of total emissions; energy (including transport), 41%; industry, 6.1%; waste, 5.1%.[6] In other Kyoto Protocol Annex 1 countries, agriculture typically contributes about 11% of total emissions.[9]

Between 1990 and 2016, New Zealand emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) increased by 35.4%; methane (CH4) by 4.4%; and nitrous oxide (N2O) by 27.6%. hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) have also gone up. Emissions of perfluorocarbons (PFCs) have decreased by 94.6%; sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) decreased by 13.4%. Overall, these figures represent a total CO2-equivalent increase of 19.6%.[10]

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme, which came into effect in 2008, was intended to provide a mechanism which encouraged different sectors of the economy to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. It may have slowed the increase somewhat. Between 2007 and 2017 total national emissions decreased 0.9%, reflecting growth in renewable energy generation.[11] However, between 2016 and 2017, New Zealand's gross emissions jumped 2.2 %, bringing the total (or gross) increase in greenhouse gas emissions between 1990 and 2017 to 23.1%.[12] Net emissions (after subtracting land use change and forest sequestration removals) increased by 64.9%. Emission increases by sector were – agriculture; 13.5%, energy; 38.2%, industry; 38.8%. waste; 2.1%.[6]

The 2019 Greenhouse Gas Inventory noted that in 2017, New Zealand's per capita emissions of the six greenhouse gases listed in the Kyoto Protocol were 16.9 tonnes CO2 equivalents per head of population.[13] In 2018, on a per capita basis, New Zealand was the 21st biggest contributor to global emissions in the world and fifth highest in the OECD.[14]

Carbon dioxide[]

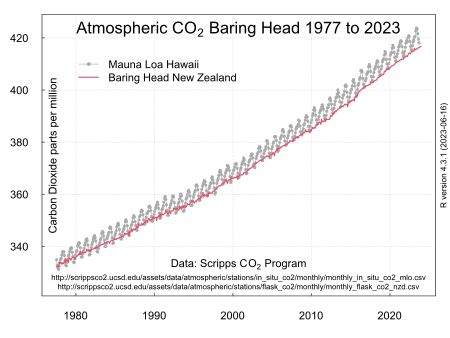

New Zealand has a long-term record of atmospheric carbon dioxide similar to the Keeling Curve. In 1970, Charles Keeling asked David Lowe, a physics graduate from Victoria University of Wellington to establish continuous atmospheric measurements at a New Zealand site. The south-facing Baring Head, on the eastern entrance to Wellington Harbour, was chosen as being representative of the atmosphere of the southern hemisphere. Despite the majority of CO2 emissions coming from the Northern Hemisphere, the atmospheric concentration in New Zealand is similar.[15] The Baring Head records show that CO2 concentrations rose from 325 ppm in 1972 to 380 ppm in 2009,[16] and over 400 ppm in 2015.[17]

Modelled wind directions indicated that air flows were originating from 55 degrees south. The Baring Head data shows about the same overall rate of increase in CO2 as the measurements from the Mauna Loa Observatory, but with a smaller seasonal variation. The rate of increase in 2005 was 2.5 parts per million per year.[18] The Baring Head record is the longest continuous record of atmospheric CO2 in the Southern Hemisphere and it featured in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007 in conjunction with the better-known Mauna Loa record.[19]

According to estimates from the International Energy Association, New Zealand's per capita carbon dioxide emissions roughly doubled from 1970 to 2000 and then exceeded the per capita carbon dioxide emissions of either the United Kingdom or the European Union.[20] Per capita carbon dioxide emissions are in the highest quartile of global emissions.[21]

Methane[]

The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) has also recorded atmospheric concentrations of methane (from 1989) and nitrous oxide (from 1997) at Baring Head.[22] More than 80% of methane emissions in New Zealand come from enteric fermentation in ruminant livestock – sheep, cattle, goats and deer – with sheep the greatest single source.[23]

This emissions profile is significantly different to that of other countries as, internationally, the dominant sources of methane are rice paddies and wetlands. As a greenhouse gas, methane is 28 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.[24] A dairy cow produces between 84 and 123 kg of methane per year from rumen fermentation.[25] Since New Zealand has large stock numbers these emissions are significant. In 1997, New Zealand's per capita emissions of methane were almost six times the OECD average and ten times the global average[26] In other words, on a per capita basis, New Zealand has the largest methane emission rate in the world.

In 2003, the Government proposed an Agricultural emissions research levy to fund research into reducing ruminant emissions. The proposal, popularly called a "fart tax", was strongly opposed by Federated Farmers and was later abandoned.[27] The Livestock Emissions and Abatement Research Network (LEARN) was launched in 2007 to address livestock emissions.[28] The Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium between the New Zealand government and industry groups seeks to reduce agricultural emissions through the funding of research.

At the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, the New Zealand government announced the formation of the Global Research Alliance involving 20 other countries. New Zealand will contribute NZ$45 million over four years towards research on agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.[29]

In 2019, it was announced that the government had awarded funding to cultivate and research a red native seaweed known as Asparagopsis armata to the Cawthron Institute in Nelson. This particular seaweed has been found to reduce methane emissions from animals by as much as 80% when small amounts (2%) are added as a supplement to animal food.[30]

Nitrous oxide[]

Nitrous oxide is emitted primarily from agriculture, but also comes from industrial processes and fossil fuel combustion. Over 100 years, it is 298 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat. In New Zealand in 2018, 92.5 % of N2O came from agricultural soils mainly due to urine and dung deposited by grazing animals. Overall, N2O emissions increased 54 % from 1990 to 2018 and now make up 19% of all agricultural emissions.[31]

By sector[]

Averaging total emissions in New Zealand down to an individual level, each New Zealander contributes about 6,000 kg of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere every year. One third of that (2,000 kg) comes from all the food we[clarification needed] eat which involves the release of carbon dioxide[clarification needed] to produce it; 1,600 kg comes from New Zealanders use of cars and planes for travel; 1,500 kg comes from our use of electricity; the remaining 900 kg comes from other kinds of consumption such as the purchase[clarification needed] of clothes.[32]

Agriculture[]

The agriculture industry is responsible for half of all emissions in New Zealand, but contributes less than 7 % of the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the last ten years[when?] there have been modest reductions in emissions from sheep, beef, deer and poultry farms, but these have been offset by a rapid growth in dairy farming which has had the biggest increase in emissions of any single industry. In fact, emissions from dairy have risen 27% over the decade such that this industry is now responsible for more emissions than the manufacturing and electricity and gas supply industries combined.[33]

Food processing[]

Dairy giant Fonterra is responsible for 20% of New Zealand's entire greenhouse gas emissions.[34] This is largely due to Fonterra's use of coal-powered boilers to dry milk into milk powder. Clean energy expert, Michael Liebreich, describes the use of coal for this process as "insane". Genesis Energy Limited chief executive, Marc England, said in 2019 that Fonterra is using more coal than Genesis uses at its Huntly power station and should use electricity, which is already 85% renewable, in its milk powder factories.[35]

Electricity[]

Both historically and presently, the majority of New Zealand's electricity has been generated from hydroelectricity. In the 2019 calendar year, 82.4% of the country's electricity was generated from renewable or low-carbon resources: 58.2% from hydroelectricity, 17.4% from geothermal, 12.6% from natural gas, 5.1% from wind, 4.9% from coal, and 1.7% from other sources.[36]

The Huntly Power Station consumes about 300,000 tonnes of coal every year[37] and is one of the biggest carbon dioxide generators in the country contributing over half of New Zealand's emissions of greenhouse gases from electricity generation.[38] According to Chris Baker, chief executive of Straterra, "that scenario won't change for years to come."[37] Only 10% of the power from the Huntly plant is used by Genesis Energy Limited itself. The remaining 90% is sold to other electricity companies to ease their own supply issues. In February 2018 Genesis Energy said it may keep burning fossil fuels until 2030.[39]

A major barrier in decommissioning Huntly is ensuring continued security of supply, especially to Auckland and Northland. In June 2019, transmission grid operator Transpower analysed the effects of closing the two remaining coal-fired units at Huntly on its grid. It concluded that without the coal-fired units and no major new generation or transmission upgrades, voltage collapse could occur during Auckland and Northland winter peak demand from 2023 onwards with the 400 MW combined-cycle gas turbine Huntly Unit 5 out of service, or from 2019 onwards with both Huntly Unit 5 and any one of the 220,000-volt transmission lines from Whakamaru out of service.[40]

Ten biggest polluters[]

The ten companies which emit the most greenhouse gases in New Zealand are Fonterra, Z Energy, Air New Zealand, Methanex, Marsden Point Oil Refinery, BP, Exxon Mobil, Genesis Energy Limited, Contact Energy, and Fletcher Building. These companies emit around 54.5 million tonnes of CO2 each year – more than two thirds of New Zealand's total emissions.[41]

Favourable treatment for high polluters[]

The seven biggest industrial emitters in New Zealand are Fonterra, NZ Steel, New Zealand Aluminium Smelters (which operates the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter), NZ Refining, , Methanex and . According to business journalist Rod Oram, for years these companies have been the main beneficiaries of favourable Government policies designed to minimise the impact of the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme on companies which are emissions intensive and trade exposed (EITE). In 2017 these companies (plus another three of the largest emitters) received 90 % of the free credit allocations - essentially a licence to continue polluting - offered by the Government under the scheme.[34][needs update]

Households[]

Household emissions now comprise 11% of all emissions, up from 9% in 2007.[citation needed] The bulk of household emissions stem from New Zealander's reliance on combustion engine cars for transport - with relatively small amounts coming from heating and cooling.[33] In 2019, there were less than 10,000 electric vehicles on New Zealand roads leading the New Zealand Productivity Commission to recommend a rapid and comprehensive switch from petrol cars to EVs. Professor David Frame, director of Victoria University's New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute says "the growth (in use) of electric cars has been nowhere fast enough to get to where we've said we want to be by 2030".[42]

In the last ten years,[when?] New Zealand and Australia were among a handful of developed nations where household emissions are increasing. The others are all Eastern European countries.[33] A New Zealand study conducted in 2019 says housing must shrink its carbon footprint by 80% to meet New Zealand's commitment to the Paris climate accord adding that a typical new Kiwi home emits five times as much carbon dioxide as it should if the world is to stay below 2C warming.[43]

Transportation[]

Road & rail[]

Due to the growth in the number of vehicles on New Zealand roads (now more than four million vehicles) emissions from transport have grown 78% since 1990[44][45][needs update] and are now the second-largest source of the country's greenhouse gas emissions. Road transport contributes 45% of all emissions from the burning of fossil fuels in New Zealand.[45] New Zealanders tend to buy big cars, SUVs and utes,[44] and for this reason our average vehicle CO2 emissions per head of population is high compared to other developed nations,[46] such that the country's transport emissions per person are the fourth highest in the world.[44]

One reason for this is that New Zealand is one of only three countries without fleet-wide vehicle emissions standards[47] leading the New Zealand Productivity Commission to argue the country is "becoming a dumping ground for high-emitting cars from other nations busy decarbonising their highways".[42] As a result, there has been little incentive for the public to buy electric cars or hybrids; as at May 2019, only 61,000 hybrid vehicles were registered in New Zealand.[48][needs update]

However, in July 2019, Associate Transport Minister Julie Anne Genter announced a government proposal to impose substantial price discounts on imported cars with low emissions and price penalties on those with high emissions. This would knock about $8,000 off the price of new or near-new imported electric vehicles (EVs) while the heaviest petrol using polluters would cost $3,000 more. The scheme is expected to remove more than five million tonnes of CO2 from New Zealand's emissions even though it only applies to (new and used) vehicles coming into the country and does not apply to the 3.2 million vehicles already on the roads which account for 74% of annual sales.[49][50]

Around 589 km (366 mi) of New Zealand's 4,128 km (2,565 mi) of railway track is electrified. This includes the majority of the Auckland and Wellington regional commuter networks (with the notable exception of Papakura to Pukekohe and Wellington to Masterton services), and the central section of the North Island Main Trunk between Hamilton and Palmerston North. There is no electrified track in the South Island.

Air travel[]

Air New Zealand is one of the country's largest climate polluters, emitting more than 3.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. This represents about 4% of New Zealand's total greenhouse gas emissions. Air New Zealand offers a voluntary scheme, called FlyNeutral, which allows passengers buy carbon credits to offset their flights. Currently customers offset less than 1.5% of the airline's total carbon emissions. Air New Zealand also offsets its domestic emissions through the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme. The airline says that in 2019 it will purchase emission units to cover 100 % of its domestic carbon footprint.[51]

Impacts on the natural environment[]

Temperature and weather changes[]

New Zealand has reliable air temperature records going back to the early 1900s. Temperatures are taken from seven climate stations throughout the country and combined into an average. According to NIWA, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, between 1909 and 2018 the air around New Zealand has warmed 1.09 °C.[52]

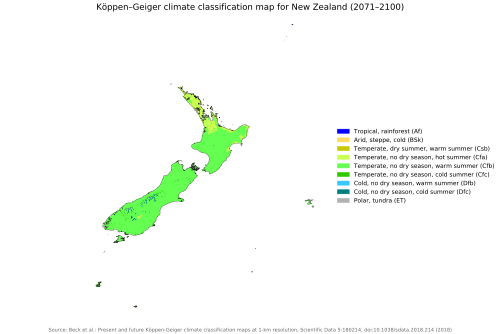

Temperatures are expected to warm by at least 2 °C by the end of the century[53] although an Australian report released in 2019 called Breakthrough, says the plans that countries have put forward for cutting emissions in Paris will lead to around 3 °C of warming. Breakthrough says warming will be even higher than that because the model used does not include long-term carbon cycle feedback loops.[54]

Ecosystems[]

The Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand has pointed out that New Zealand's native plants and animals are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. More frequent storms combined with rising sea levels will make it harder for seabirds like hoiho (yellow-eyed penguin) to find food. Warmer temperatures will lead to more frequent mast events (sudden abundance of food in an area of forest leading to huge population irruptions of mice, rats and stoats). This puts greater pressure on native species like kiwi which are already in trouble. Warmer temperatures also allow pests and weeds will extend their range, and new pests and diseases will begin to appear. Tuatara eggs are also sensitive to temperature: fewer female tuatara will hatch, threatening the survival of our largest reptile.[55]

Glaciers[]

New Zealand has over 3,000 glaciers, most of which are in the South Island.[57] Since 1977, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) has been using aerial surveys of late summer snowline to estimate the mass balance of 50 index glaciers. The snowline marks the equilibrium line of a glacier; above the line the glacier is accumulating snow and below the line the glacier is melting. The mass balance is the net gain or loss of snow and ice. [58] A survey by NIWA in 2009 says the volume of ice in New Zealand's glaciers declined by about 50% in the last century, while New Zealand's average temperature increased by about 1 °C.[59]

In 2017, NIWA published new research in the scientific journal, Nature Communications, showing that between 1983 and 2008, regional climate variability caused more than 50 of New Zealand's glaciers to grow in contrast to international trends. Lead author Associate Professor Andrew Mackintosh from Victoria's Antarctic Research Centre said: "Glaciers advancing is very unusual — especially in this period when the vast majority of glaciers worldwide shrank in size as a result of our warming world."[60] Mackintosh said glaciers grew because temperatures dropped as a result of variability in the climate system specific to New Zealand. He does not expect this unusual trend to continue saying: "If we get the two to four degrees of warming expected by the end of the century, our glaciers are going to mostly disappear."[60]

New Zealand's largest glacier, the Tasman Glacier has retreated about 180 metres a year on average since the 1990s and the glacier's terminal lake, Tasman Lake, is expanding at the expense of the glacier. Massey University scientists expect that Lake Tasman will stabilise at a maximum size in about 10 to 19 years, and eventually the Tasman Glacier will disappear completely. In 1973 the Tasman Glacier had no terminal lake and by 2008 Tasman Lake was 7 km long, 2 km wide and 245 m deep.[61] Between 1990 and 2015, Tasman Glacier retreated 4.5 kilometers (2.8 miles), mostly from calving.[62]

Climate change has caused New Zealand's glaciers to shrink in total volume by one third in the last four decades. Some glaciers have already disappeared completely. As at 2017, the area covered by New Zealand's glaciers shrank from 1240sq km to 857sq km - a decrease of 31% since the late 1970s. This is a loss of just under 1% a year, although the rate is speeding up with the biggest melt occurring in a record-hot summer of 2017/18.[63] Climate scientist, Jim Salinger said the decline will affect skiing and tourism, and cause problems for South Island farmers in particular. He also said: "This would mean that ice melt from our mountain glaciers will predominate during the 21st century with Aotearoa, land of the long white cloud, becoming Aoteapoto – the land of the short white cloud."[64]

Sea level rise[]

Twentieth century[]

An analysis in 2004 of long term records from four New Zealand tide gauges indicated an average rate of increase in sea level of 1.6 mm a year for the 100 years to 2000, which was considered to be relatively consistent with other regional and global sea level rise calculations when corrected for glacial-isostatic effects.[65] One global average rate of sea-level rise is 1.7 ± 0.3 mm per year for the 20th century (Church and White (2006).[66] Another global average rate of sea-level rise is 1.8 mm/yr ± 0.1 for the period 1880–1980.[67]

A 2008 study of cores from salt-marshes near Pounawea indicated that the rate of sea level rise in the 20th century, 2.8 ± 0.5 mm per year, had been greater than rate of change in earlier centuries (0.3 ± 0.3 mm per year from AD 1500 to AD 1900) and that the 20th century sea level rise was consistent with instrumental measurements recorded since 1924.[68]

Twenty-first century[]

Predictions about sea level rise vary considerably. In November 2014, Dr Jan Wright, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment released a report titled Changing climate and rising seas: Understanding the science[69] which says that the sea level is ‘locked in’ to rise by about 30 centimetres by 2050. However, a 2016 report published by the Royal Society of New Zealand finds it likely that the sea level around New Zealand will rise by more than a metre by the end of the century and will exceed the global average by 5–10%.[70] Projections of future sea level rise depend on which carbon emission scenario model is used. Research in 2019 based on a two degree increase in temperature, which is scenario consistent with the Paris Agreement, leads to a possible 81 cm rise by 2100. An Australian policy paper published by Breakthrough in May 2019 predicts a three degree rise in temperature leading to a sea level rise as high as three metres.[71]

In 2016, the Royal Society of New Zealand stated that a one-metre rise would cause coastal erosion and flooding, especially when combined with storm surges.[3][72] Climate scientist Jim Salinger commented that New Zealand will have to abandon some coastal areas when the weather gets uncontrollable.[73]

Associate Professor Nancy Bertler, of the Joint Antarctic Research Institute, at Victoria University of Wellington says: "New research suggests that sea level could rise as quickly as four metres per 100 years (or one metre per 25 years). Assuming even a modest global sea level increase of 50 cm by 2100 (IPCC scenario RCP 4.5), the frequency of coastal inundation in New Zealand is predicted to increase by a multiplier of 1000 times."[74]

Rising sea levels will further threaten coastal areas and erode and alter landscapes whilst also resulting in salt water intrusion into soils, reducing soil quality and limiting plant species growth.[75] The Ministry for the Environment says by 2050–2070, storms and high tides which produce extreme coastal water levels will occur on average at least once a year instead of once every 100 years. GNS climate scientist Tim Naish, says in the event of a two-metre rise in sea-level by the end of the century, one-in-100-year flooding event will become a daily event. Naish says: “We are a coastal nation so we are going to get whacked by sea-level rise. In many areas, we have to retreat "which comes with massive disruption and social and economic issues.”

Twelve of the fifteen largest towns and cities in New Zealand are coastal with 65% of communities and major infrastructure lying within five kilometres of the sea.[76] As flooding becomes more frequent, coastal homeowners will experience significant losses and displacement. Some may be forced to abandon their properties after a single, sudden disaster like a storm surge or flash flood or move away after a series of smaller flooding events that eventually become intolerable. Local and central government will face high costs from adaptive measures and continued provision of infrastructure when abandoning housing may be more efficient.[77]

In Auckland, the CBD, eastern bays, Onehunga, Māngere Bridge, Devonport and Helensville are the most vulnerable to inundation.[78]

Wellington is anticipating a 1.5 metre rise which could see much of the central city and low-lying suburbs under water. Areas likely to be inundated include the area around Westpac stadium, swathes of land through the central city, as well as lower parts of Oriental Bay, Evans Bay, Kilbirnie, Shelly Bay, Seatoun, the South Coast bays, parts of Petone, Waiwhetu and the eastern bays as well as much of low-lying areas at Mākara Beach, Pauatahanui, and Kapiti.[79]

Wildfires[]

Summers are getting longer and hotter such that four of the last six years have been New Zealand's warmest on record. Scion Rural Fire Research Group fire scientist, Grant Pearce, says the number of days that the risk of dangerous fires breaking out in some parts of New Zealand could double by 2050. The Pigeon Valley fire in Nelson in 2019 was New Zealand's largest forest fire in 60 years. It covered more than 2,300 hectares prompting an independent review of fire risk which found wildfires would occur more frequently because of drier conditions. The risk will escalate due to increases in temperature, wind speed and lower rainfall associated with global warming. The Lancet reports that the health effects of wildfires range from burns and death, to the exacerbation of acute and chronic conditions.[80]

Impacts on people[]

The combined effects of climate change will result in a multitude of irreversible impacts on New Zealand. By the end of this century New Zealand will experience higher rainfalls, more frequent extreme weather events, rising sea levels and higher temperatures.[75] Such effects will significantly impact New Zealand, with higher temperatures resulting in dry summers, consequently limiting New Zealand's water supply and intensifying droughts.[75] The Ministry for the Environment says the greatest effect of climate change is likely to be on New Zealand's water resources, with higher rainfall in the west and less in the east. Extreme climate events such as droughts could become more frequent in eastern areas, with increased flooding after major downpours.[81]

Higher temperatures are likely to increase problems such as heat stress in summer and mortality is expected to rise due to harsher living environments. Disease-transmitting insects such as mosquitoes could become established more easily as the climate warms.[81] Rising temperatures will also have devastating effects on New Zealand's flora and fauna, with climate threatening both animal and plant chances of survival.[75][failed verification]

Sir Peter Gluckman, the Prime Minister's Chief Science Advisor, noted in 2013 that even "the magnitude of environmental changes (in New Zealand) will depend in part on the global trajectories of greenhouse gas emissions and land use change, (and that) effective risk management requires consideration of the possibility of experiencing more extreme components of the predictive range".[15]

Economic impacts[]

Droughts and lack of water will not only affect the environment, this will also impact on the economy as New Zealand's agricultural export sector strongly relies on an environment conducive to growing crops and livestock.[82] For instance, higher temperatures could cause problems for fruit growers in northern areas because plants such as kiwifruit require cold winters. Pests and diseases could spread more easily under warmer conditions and pasture composition may change with the spread of subtropical grasses. Increased costs will be incurred by farmers as land-use activities shift while adapting to changes in the climate.[81]

Loss of insurance cover[]

The Insurance Council of New Zealand (ICNZ) says houses and buildings in vulnerable areas will eventually become uninsurable. In the Bay of Plenty some properties have already been declared “unliveable” due to severe flooding risk.[83] The Hutt City Council has issued a report which says large parts Petone including Seaview, Alicetown and Moera could be under water before the end of the century and suggests home owners in these suburbs could find their homes uninsurable in as little as 30 years.[84]

Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ) reports that over $5 billion in local government infrastructure is at risk of damage from a one-metre sea level rise.[85] However, this does not include the exposure of houses, businesses or central government assets and ICNZ claims full exposure for a one-metre rise in sea level is likely to be closer to $40 billion[86] affecting 125,000 buildings. Another $26 billion and a further 70,490 buildings would be at risk if seas rose between one and two metres. If the increase was up to three metres, which is projected in some scenarios, another 65,530 buildings would be at risk costing an additional $20 billion. So in the worst-case scenario, by the end of the century, over 260,000 buildings in coastal areas could be destroyed with projected losses of around $84 billion.[87]

Potential costs[]

The economic loss associated with soil erosion and landslides is already estimated at up to $300 million a year. Freshwater scientist Mike Joy says that in the last 20 years or so, the loss of sediment into waterways has also had a significant detrimental effect on water quality.[88]

In April, 2019 Judy Lawrence from Victoria University's Climate Change Research unit suggested a climate change fund similar to the Earthquake Commission needed to be set up to pay for climate change adaptation. She said that "Local Government New Zealand have done a recent assessment of the costs and they are talking of $14 billion" although "we think that is an underestimate of the real cost". James Palmer, chief executive of the Hawke's Bay Regional Councils, said local authorities were already facing up to the dangers from coastal erosion, but "What we don't know is what contribution the Crown would be willing to make, both to safeguard its own assets, but also, more broadly, on behalf of the wider communities."[89]

Agriculture[]

As temperatures rise, more frequent and severe water extremes, including droughts and floods, will impact on agricultural production. Rising temperatures will also lead to increased water demand for farming and agriculture. Due to chronic water shortages and desertification in food growing regions, internationally, crop yields are predicted to drop by 20% by 2050 combined with a decline in nutritional content.[90] Prices are likely to skyrocket, while job losses and reduced incomes will further reduce people's capacity to purchase food. New Zealand researcher, associate professor Carol Wham, says malnutrition is "associated with higher infection rates, loss of muscle mass, strength and function, longer hospital stays, as well as increasing morbidity and mortality."[91]

Health impacts[]

In 2018, the American Psychological Association issued a report about the impact of climate change on mental health. It said that "gradual, long-term changes in climate can also surface a number of different emotions, including fear, anger, feelings of powerlessness, or exhaustion".[92][93] The NZ Psychological Society reports similar findings. It says clients are presenting with "a lot of helplessness, a lot of anxiety and some depression" brought about by climate change. In 2014, the Psychological Society set up a 'Climate Psychology Taskforce'. Task force co-convener, Brian Dixon, said psychologists were seeing the effects of climate change showing up in people of all ages. However, young people are most at risk, including the risk of suicide because of climate change. Dr Margaret O'Brien says some young people are saying, "what's the use, if this is going to happen, why should I go ahead?" The society says taking action to address the issue is the best "antidote".[94]

A report titled The Human Health Impacts of Climate Change for New Zealand points out that the most vulnerable sectors are children, the elderly, those suffering with disabilities or chronic disease, and those on low-incomes. Also at risk are those have an economic base invested in primary industries, those who experience housing and economic inequalities, especially low income housing in areas vulnerable to flooding and sea level rise.[95] Environmental concerns are even affecting New Zealanders' plans for the future leading some young women to decide not to have children. Those who make this decision believe any children they might bring into the world would face lives full of hardship and conflict due to lack of natural resources and, by adding to the population, would actually cause more harm to the planet.[93]

[]

If greenhouse gas emissions continue at current levels, many places in New Zealand will see more than 80 days per year above 25 °C by 2100. Currently most parts of the country typically see between 20 and 40 days per year above 25 °C. The elderly populations are particularly vulnerable to heatwaves. In Auckland and Christchurch, a total of 14 heat-related deaths already occur each year amongst those over 65 when temperatures exceed 20 °C. Approximately a quarter of New Zealanders are projected to be 65 and over by 2043, so heat-related deaths are likely to rise.[96]

Impacts on indigenous peoples[]

A report in 2017, Adapting to Climate Change in New Zealand, identifies Māori as among the most vulnerable groups to climate-change in New Zealand due to their "significant reliance on the environment as a cultural, social and economic resource".[97] Māori tend to be involved in primary industries, and many Maori communities were near the coast. The report states that urupā (burial grounds) and marae are already being flooded or washed into the sea.

Mike Smith, of Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Kahu, says the Government is failing in its duties under the Treaty of Waitangi to protect Māori, who are particularly vulnerable, from the "catastrophic effects of climate change". Smith has filed proceedings in the High Court "on behalf of my children, grandchildren and the future generations of Māori children, whose lives are threatened by the climate crisis".[98]

Impacts on migration[]

If the atmosphere warms by two degrees Celsius, small island countries in the Pacific will be inundated by sea level rise. These islands do not have the populations or resources to deal with weather related disasters. Currently, 180,000 people living in low-lying islands like Kiribati, Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands are the most threatened. More extreme projections suggest that by 2050, 75 million people from the wider Asia-Pacific region will be forced to shift.[99]

Pacific islanders forced to relocate will be at higher risk of developing mental health problems because of losing their homes, their culture and the stress of climate-induced migration.[99] The New Zealand Defence Force is predicting an increase in the number of humanitarian and disaster relief operations it will attend in the Pacific due to climate change.[100]

One analysis suggests that as one of the few habitable areas left on the planet, New Zealand "would likely become overcrowded, under constant threat of flood and cyclone, and increasingly infested by flies and other insects."[101]

Mitigation[]

Carbon tax[]

Preparing to meet its commitments, in 2002 the Labour Party decided to implement a carbon tax, beginning in 2007. The proposed carbon tax would have applied to emissions from every sector of the whole economy, except for agricultural methane and nitrous oxide. The carbon tax policy was intended to be a precursor to emissions trading when it became internationally established.[102] However, New Zealand First and United Future, Labour's support parties in the Government were opposed to the policy.[103] In December 2005, the Coalition Government announced that following a review of climate change policy it would not implement the proposed tax.[104]

The Green Party described the withdrawal the carbon tax as "giving up on climate change" and "capitulating" to the anti-Kyoto lobby.[105] The Environmental Defence Society described the withdrawal of the carbon tax as "pathetic" and a result of the NZ Government Climate Change Office being "captured" by vested interests such as energy intensive businesses and the Greenhouse Policy Coalition.[106]

Emissions trading scheme[]

After scrapping its plans for the carbon tax, in September 2008 the Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand passed the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act 2008 with support from the Green Party and New Zealand First.[107] establishing the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS). It was amended in November 2009[108] and in November 2012[109] by the Fifth National Government of New Zealand.

As of 2018, the system applies to about 51% of New Zealand's gross emissions and covers almost all emissions from fossil fuels, industrial processes and waste. It also applies unit obligations for deforestation and credits for eligible afforestation. However, it does not apply to emissions from agriculture, which account for about 49% of New Zealand's gross emissions. Economic sectors which are legally obligated to participate are required to surrender to the government a tradable emission unit for each tonne of emissions for which they are liable.[110] In other words, the scheme charges polluters for increases in emissions and rewards those who cut emissions. This creates an incentive for businesses and consumers to reduce or avoid emissions.[110]

In addition to allowing the purchase of Kyoto units on the international market, the scheme created a specific domestic unit called the 'New Zealand Unit' (NZU), which has been issued to emitters for free.[111] The number of free units allocated to eligible emitters was based on the average emissions per unit of output within a defined economic 'activity'.[112] The allocation of free units allowed emissions-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE) activities, such as steel and aluminium, to continue operating in New Zealand rather than driving such industries offshore where they would continue producing the same level of emissions.[113]

First commitment period 2008–2012[]

New Zealand's target was expressed as an "assigned amount" of allowed emissions over the five-year 2008–2012 commitment period.[114] The Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) believed New Zealand would actually be able to increase emissions and still comply with the Kyoto Protocol as long as more Removal Units were obtained from forest carbon sinks between 2008 and 2012.[114] The chart (right) shows that New Zealand did emit more than 100% of greenhouse gasses (at the 1990 level) during this period.

In June 2005, a financial liability under the Kyoto Protocol for a shortfall of emission units of 36.2 million tonnes of {{CO2}}-e was first recognised in the Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand. It was estimated as a liability of $NZ310 million.[115] New Zealand's net balance under the Kyoto Protocol remained in deficit from 2005 (a deficit of 36 million units)[116] until May 2008 (a deficit of 21.7 million units).[117]

Doha Amendment 2013–2020[]

The second commitment period (2013–20) was established in Doha in 2012, although New Zealand refused to take on any new targets during this period. Instead, in November 2012, the New Zealand Government announced it would make climate pledges for the period from 2013 to 2020 under the UNFCCC process rather than agree to a second commitment under the Kyoto Protocol.[118][119]

This announcement angered environmentalists and was reported internationally as New Zealand avoiding legally binding obligations.[120] Green Party climate change spokesman Kennedy Graham said the Government's announcement was about hot air at talks instead of legally binding measures to reduce emissions.[121] The decision was also heavily criticised by the World Wildlife Fund.[122] Prime Minister John Key said New Zealand should not lead the way on climate change, but instead be a "fast follower".[123] The Alliance of Small Island States voiced disappointment at New Zealand's decision.[124]

In August 2013, the National Government announced a target to reduce New Zealand's emissions to 5% less than total emissions in 1990 by the year 2020. Tim Groser, the Minister for Climate Change issues noted that New Zealand would still honour its conditional offer made in 2009 to reduce emissions to 10 – 20% below 1990 levels – but only if other countries come on board.[125]

Criticisms[]

Labelling the National Government's commitment a 'failure', Global conservation organisation, WWF, pointed out that a 5% reduction is well below the level recommended by scientists in order reduce the damage of anthropogenic climate change.[126] The changes to the scheme also allowed an influx of cheap, imported international emission units that collapsed the price of the New Zealand unit. This effectively undermined the whole scheme.[113] The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment also criticized the Scheme for its generous free allocations of emission units and the lack of a carbon price signal.[127] Greenpeace Aotearoa New Zealand criticised it for its total ineffectiveness at reducing emissions.[128]

In May 2011, the climate scientist James Hansen visited New Zealand for a speaking tour. Hansen drew huge crowds for his public talks. He said he did not agree with schemes like the NZETS which included forestry offsets. "In my opinion you have to have the simplest, transparent scheme so I just say it should be a flat fee proportional to the amount of carbon in the fuel."[129]

In 2014, the New Zealand Climate Party stated the emissions trading scheme "degenerated into a farce because the current emissions charges are far too low to address our steadily climbing emissions levels or to cover the damage these emissions are causing".[130] In June 2019, Peter Whitmore, executive member of Engineers for Social Responsibility and founder of the Climate Party said: " We need to rapidly phase out the provision of free emissions units to trade exposed industries" as, in practice, they incentivize these industry to continue polluting.[131]

Current responses[]

Mining on conservation land[]

There are currently 54 active mines[clarification needed] on conservation land in New Zealand covering 8.68 million hectares. In November 2017, one of the new Government's first announcements was that new mining projects on conservation land would be banned. Then in May 2018, Conservation Minister Eugenie Sage said feedback would be sought from stakeholders and a discussion document would be released first. As at March 2019, the document still had not been released raising concerns that the slowprocess was allowing the mining industry to take advantage of the delay in implementing the ban.[132] The delay in legislation to back up the commitment has meant that by March 2020, 21 mining applications had been approved on conservation land since Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern promised this would be stopped.[133]

Offshore oil & gas permits[]

Currently Taranaki is the only oil and gas producing region in New Zealand's with more than 20 fields, on and offshore. In 2013 about 4,300 workers were employed in sector in Taranaki.[134] In 2018 when the Sixth Labour Government of New Zealand came to power, it ceased issuing new offshore oil and gas exploration permits.[135] The Petroleum Exploration and Production Association of New Zealand (PEPANZ) which lobbies on behalf of the industry has been highly critical of the exploration ban. PEPANZ points out that the oil and gas sector contributes $1.5bn to Taranaki's GDP and makes up 40% of the regional economy.[134]

The Government's decision does not affect the reserves or potential finds from these active exploration permits.[136] Energy Minister Megan Woods said this will lead to a long-term, managed transition away from oil and gas production over the next 30 years.[137] In 2018, Simon Bridges said the National Party "would bring back oil and gas exploration immediately if National was returned to government". He said: "[It's] no good us doing everything and no-one else doing anything. That will still mean the world gets warmer..."[138]

Tree planting[]

The Labour led coalition has established a goal to plant one billion trees within ten years (by 2028)[139] because trees absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere in a process known as carbon sequestration potentially helping New Zealand to become carbon neutral. According to the Forest Owners Association, in 2015 New Zealand forests held 283 million tonnes of carbon.[140]

Under the new scheme, $120 million has allocated for landowners to plant new areas and $58 million to establish Te Uru Rākau forestry service in Rotorua. The plan is also designed to encourage farmers and Maori land holders to include trees on their property.[141] However, Bay of Plenty and Taupo contractors are struggling to find workers to do the planting, even though the pay is $300 to $400 a day.[142] As at 27 July 2018, nine million trees, 13% of them native species had been planted.[143]

Concerns: New Zealand emits over 80 million tonnes of greenhouse gases (measured in CO2-equivalents) every year, approximately 45% of which (36 million tonnes) is CO2.[144] Between 1990 and 2016, the net uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) decreased by nearly 23 % (down to 23 million tonnes a year) due to more intensive harvesting of planted forests.[145] On top of this, a typical hardwood tree takes about 40 years to remove approximately one ton of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[146]

Climate scientist Jim Salinger and anthropologist and environmentalist Dame Anne Salmond have criticised the plan to plant one billion trees because only 13% of the trees that have been planted are natives. Salmond says two thirds of the trees being planted are supposed to be natives.[147] Salinger points out that pine forests store far less carbon than natives as they are harvested after a few decades; the trees end up as pulp and paper and the carbon goes back into the atmosphere. Natural (native) forests store 40 times more carbon than and plantations like pine trees.[148] A report released by the Productivity Commission in August 2018 also found that one billion tree plan is only a fraction of what is required to offset the amount carbon being released in New Zealand. The Commission says the planting rate needs to double, from 50,000 hectares to 100,000ha per year and the length of the programme needs to be extended from 10 to 30 years.[149] Conservation charity, Trees That Count, monitors the number of native trees planted throughout New Zealand.[150]

Carbon Zero Act[]

In 2019, the Labour led coalition introduced the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act which sets a target of zero carbon emissions for New Zealand by 2050. The Bill passed into law in November 2019 with almost unanimous support.[151] It establishes an independent Climate Change Commission to advise the Government of the day on emissions reduction pathways, progress towards targets and develop regular five-year emission budgets. The act sets a separate target for methane gas emissions which mostly come from the agricultural sector – requiring a 10% reduction in biological methane by 2030 and a provisional reduction between 24%–47% by 2050.[152]

Greenpeace New Zealand executive director, Russel Norman criticised the bill because the targets are voluntary and have no enforcement mechanisms. He says: “What we’ve got here is a reasonably ambitious piece of legislation that’s then had the teeth ripped out of it. There’s bark, but there’s no bite."[153]

Independent scientific analysis by Climate Action Tracker[154] notes that "The Bill does not introduce any policies to actually cut emissions". It also rates New Zealand's emissions targets as "insufficient" meaning that our goals are not "consistent with holding warming below 2C, let alone with the Paris Agreement's stronger 1.5C limit".[155] This is the sixth time in a row that New Zealand's response to the climate crisis has been ranked as "insufficient".[156]

Policies and legislation[]

Political initiatives[]

In 1988, the same year as the United Nations established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Fourth Labour Government of New Zealand started developing policy for climate change. This was coordinated between agencies by the Ministry for the Environment.[157] The Government asked the Royal Society of New Zealand to report on the scientific basis of climate change. A short report, 'Climate Change in New Zealand', was published in 1988 and the full report 'New Zealand Climate Report 1990' was published in 1989.[158]

International cooperation[]

New Zealand ratified the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC in December 2002.[159] The Protocol, which came into effect in 2012, acknowledged that, due to varying levels of economic development, countries have different capabilities in combating climate change. Due to its status as a developed nation, New Zealand had a target to ensure that 'aggregate anthropogenic carbon dioxide equivalent emissions of the greenhouse gases listed in Annex A do not exceed' 100% of 1990 gross emissions (the baseline).[160]

New Zealand ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (the UNFCCC) in September 1993.[161] The purpose of this convention was to collectively bring countries together to discuss how to best address climate change and handle the impacts of it.[162] The convention, which included 192 nations and came into force on 21 May 1994, recognised that climate change is a serious threat and that human (anthropogenic) impact on change in climate needs to be focused on and reduced.[162] The convention also placed responsibility on developed countries to devise methods and systems to mitigate climate change and lead the way to addressing climate change for the developing world.[162] The initial ratification to this convention sparked the beginning of formal commitment to climate change and the need to consider collective methods to address and adapt to the presence of the globally threatening issue.[162]

In July 1994, four months after the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) came into force, the Fourth National Government announced a number of priorities related to New Zealand's emissions. Environment Minister, Simon Upton published the Environment 2010 Strategy laying out eleven undefined goals which didn't actually commit the Government to do anything.[163]

Paris Climate Agreement[]

The Paris Climate Agreement is the successor to the 1998 Kyoto Protocol and has set a target to keep temperature rises within two degrees Celsius this century, with the hope of limiting it to 1.5 degrees.[164] The Paris Climate Agreement negotiations concluded 12 December 2015 but the Agreement doesn't take effect until 2020.[165]

The key difference between the Paris Climate Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol is that the latter prescribed goals that were to be achieved by each signatory country and offered monetary support for developing countries. The Paris agreement allows each country to determine its own goals, defined as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The treaty uses the term ‘expectations’ in regard to reducing emissions and there are obligations on each signatory country to communicate and review their progress (NDCs) every 5 years. Countries are expected to meet their expectations, but there is no obligation to do so – and no mechanism describing how any country should go about achieving this.[166] The Paris agreement also has financial incentives available to support countries achieve their goals towards keeping the global temperature rises to below 2 degrees Celsius and down towards 1.5 degrees Celsius.[167]

New Zealand's NDC is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.[167]

Political parties stance on climate change[]

ACT Party[]

The ACT Party promotes policies associated with climate change denial. They went into the 2008 election with a policy that in part stated "New Zealand is not warming" and that their policy goal was to ensure: "That no New Zealand government will ever impose needless and unjustified taxation or regulation on its citizens in a misguided attempt to reduce global warming or become a world leader in carbon neutrality"[168] In September 2008, ACT Party Leader Rodney Hide stated "that the entire climate change – global warming hypothesis is a hoax, that the data and the hypothesis do not hold together, that Al Gore is a phoney and a fraud on this issue, and that the emissions trading scheme is a worldwide scam and swindle".[169] In October 2012, in response to a speech on climate change by Green Party MP Kennedy Graham, ACT leader John Banks said he had "never heard such claptrap in this parliament... a bogeyman tirade, humbug."[170] In 2016, ACT's only MP, David Seymour, deleted climate change policy from their website. Prior to that their website claimed New Zealand was not warming and pledged to withdraw the country from the Kyoto Protocol.[171]

However at the 2017 election, ACT did commit to replace petrol tax with a user-pays road pricing system to reduce congestion on the roads by only charging those who use them. In their transport policy, ACT argued this would make public transport faster and reduce carbon emissions.[172] Under the leadership of David Seymour the ACT party has since toned back its anti-climate change stance in favour of committing to policies that combat climate change while doing the least amount of damage to the economy. ACT was the only political party to oppose the Zero Carbon Act.[173] It is ACT's policy to repeal the ban on oil and gas exploration.[174]

Climate Change Party[]

In August 2014, Peter Whitmore launched the NZ Climate Party, although it was never formally registered. Whitmore says there is "global scientific agreement that the world’s temperature increase must be limited to 2 degrees Celsius to avoid major catastrophe"[175] and that current & past New Zealand Governments have not been taking the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions nearly seriously enough.[176] In a NZ Herald opinion piece in 2017, Whitmore wrote: "It is clear from the above that New Zealand's current Paris commitment is pathetically feeble. We are not actually undertaking to make any reduction in our emissions by 2030, even compared to today's levels".[177]

Green Party[]

Since 2014, Green Party policy has been to "establish a clear strategy, action plan and carbon budget for the transition to a net zero emissions, fossil-fuel free economy and support a 100% reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels within New Zealand by 2050".[178]

At the 2017 general election the Green Party leader James Shaw also announced that the Green Party also wanted to establish an independent climate commission.[179] The Green Party proposed a Kiwi Climate Fund to replace the Emissions Trading Scheme, charging individuals responsible for contributing to climate change pollution.[179] Commitment was also made to New Zealand having 100% renewable energy by 2030, as well as planting 1.2 billion trees, allocating 40 million dollars to native forest regeneration and creating a 100 million dollar green infrastructure fund.[179]

Labour Party[]

The New Zealand Labour Party under Jacinda Ardern set a target of net zero for greenhouse gases by the year 2050.[180] Labour committed to creating an independent climate change commission to address carbon monitoring and budgeting, and also to provide comment and guidance when set targets or goals weren't met.[180] Labour also committed to bringing agriculture into the emissions trading scheme to ensure that the agricultural sector operates with improved environmental practice.[180] Overall, Labour pledged to create a sustainable low-carbon economy, and become a leading nation in addressing climate change, successfully achieving its commitments as made under the 2015 Paris agreement.[180]

Maori Party[]

In 2017, the Maori Party committed to developing renewable energy and alternative fuels, including subsidised solar panels for all homes in New Zealand and championing their installation in schools, marae, hospitals and government agencies. It also wanted to set legally binding emission reduction targets, close all coal run power plants by 2025, support the development of renewable resources and plant 100,000 hectares of forest over the next 10 years. The Party also agreed to the establishment of an independent Climate Commission established to ensure this occurs, but also wanted subsidised electric vehicles for community groups. They also proposed a new visa category for Pacific climate change refugees.[181] However, the Maori Party lost all its seats at this election.

National Party[]

According to Colin James, the National Party "herded with" the climate change skeptics up to 2006. In May 2007, National stopped opposing the Kyoto Protocol and adopted a policy of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50 % by 2050.[182] At the 2008 election, National's policy was to honour New Zealand's Kyoto Protocol obligations and the emissions target of a 50% reduction in emissions by 2050. National proposed changing the Labour Party's emissions trading scheme to align it with the Australian Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme so that consumers and small businesses would not be penalised.[183]

Prior to the 2017 election, the National Party made a commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 30 % below 2005 levels by 2030.[184] The National Party also committed to achieving 90% of New Zealand's energy as renewable, alongside investing 4 million dollars into New Zealand becoming closer to a low carbon economy.[184] The National government also focused on transport, committing to invest in public transport, electric vehicles and cycleways to reduce use of non-renewable energy run vehicle use.[184]

In 2019, New Zealand Herald journalist Simon Wilson, argued that the National Party is New Zealand's biggest threat to addressing climate change. Writing for his newspaper, he said: "National's position on climate change will undermine our economy and damage us socially. Delays now will lead to crisis management later and the people worst affected will include farmers, coastal dwellers and the poor. As long as National holds to this position, to me it demonstrates it is unfit to govern."[185]

NZ First[]

At the 2017 election, the NZ First Party committed to setting legally binding emission reduction targets; to require electricity retailers to purchase power generated by customers at retail price; to replace the ETS with carbon budgets; and to require all government vehicles to be electricity run by the year 2025/2026.[181]

Opportunities Party[]

The Opportunity Party's policies were to set a legally binding target of carbon neutrality by 2050; reform the Emissions Trading Scheme to create a firm limit on emissions; require all large new investments take into account the goal of being carbon neutral by 2050; aim for 100% renewable electricity by 2035; and reforest all erosion-prone land by 2030.[181]

Society and culture[]

Activism[]

In March 2019, inspired by Greta Thunberg, tens of thousands of school students took to the streets across NZ calling for action on climate change. The main protests took place on 15 March 2019, however had to be abandoned for safety reasons due to the Christchurch mosque shootings on the same day. For many young people, it was the first time they felt compelled to become politically active.[186] With the headline, We need to listen to young people about climate change, an editorial on Stuff in March 2019 noted that "Many decision-makers in the governments, businesses, community organisations and churches of the world won't be alive to experience the impact of climate change. But today's school students will be."[187] Indeed, some teenagers are wondering "whether or not they will have a planet on which to live out their lives".

A Stuff survey of 15,000 readers in July 2019 shows that New Zealanders aged between 10 and 19 rated climate change as a more important issue than any other age group. Those aged between 20 and 29 were also very concerned about the issue, with the level of concern decreasing with age.[188] On 18 July, Radio New Zealand reported that youth MPs took a "bold stance" on the issue by declaring a climate change emergency at the triennial Youth Parliament for 2019.[189]

Media messaging[]

The Climate Reality Project founded by Al Gore after the release of his 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth, appoints and trains 'Climate Reality Leaders' from around the world. At a conference in Brisbane in June 2019, Gore appointed 40 New Zealanders as "apprentices" of his global climate change movement. James Shaw, who is now Minister for Climate Change Issues attended a similar conference in 2013. Part of the messaging taught at these seminars is to use the terms 'climate emergency' and 'climate crisis' rather than 'climate change'.[190] The Guardian newspaper has also decided to use the terms climate emergency, or crisis instead of climate change; and global heating instead of global warming.[191]

Media website Stuff has a dedicated section focused on the climate crisis called Quick! Save the Planet. When publishing climate related stories, Stuff includes this disclaimer: "Stuff accepts the overwhelming scientific consensus that climate change is real and caused by human activity. We welcome robust debate about the appropriate response to climate change, but do not intend to provide a venue for denialism or hoax advocacy. That applies equally to the stories we will publish in Quick! Save the Planet."[192]

Radio New Zealand points out that "Talk radio broadcasters are still happy to put hosts (such as Mike Hosking, Tim Wilson and Ryan Bridge) on the air who airily admit they don't understand the science of climate change."[193]

Opinion polls[]

Surveys carried out on public attitudes to climate change show a dramatic shift in concern between 2007 and 2019. The %age of the public perceiving it to be an urgent problem has jumped by 35% – from 8 to 43%. The number seeing it as a problem already has gone up 10% – from 16 to 26%.[194]

Year 2007 2019 An urgent and immediate problem 08% 43% A problem now 16% 26% A problem for the future 37% 13% Not really a problem 37% 11% Don't know 02% 08%

In August 2012, a Horizons poll showed that 64.4% of respondents wanted Parliament to do more to respond to global warming. 67.5% of respondents wanted business to do more to address global warming. Horizons commented that the poll "makes a strong case for more political action".[195]

In 2014, Motu Economic and Public Policy Research surveyed 2200 New Zealanders (over the age of 18) and found that at least 87% of participants are “somewhat concerned” about the effects of climate change to society in general.[196] 63% also believed that climate change would affect themselves and 58% believed that climate change would affect society.[196]

Climate emergency declarations[]

As at January 2020, 1,315 jurisdictions and local governments around the world covering 810 million citizens had declared climate emergencies.[197] What this means varies for each community and country, but common themes include a commitment to be carbon neutral as quickly as possible, limiting global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, and a willingness to share solutions and join global movements that encourage climate action.[198]

New Zealand city councils[]

The following local bodies have declared a climate emergency: Nelson (16 May 2019),[199] Environment Canterbury (23 May 2019),[200] Kapiti (23 May 2019),[201] Auckland, (11 June 2019),[202] Wellington (20 June 2019),[203] Dunedin, (25 June 2019), Hutt Valley (26 June 2019),[204] the Hawkes Bay Regional Council 26 June 2019[205] and Whangarei (26 July 2019).[206]

Making the declaration for Auckland, Mayor Phil Goff said: “Our obligation is to avoid our children and grandchildren inheriting a world devastated by global heating. Scientists tell us that if we don’t take action, the effects of heating will be catastrophic, both environmentally and economically. In declaring an emergency, we are signalling the urgency of action needed to mitigate and adapt to the impact of rising world temperatures and extreme weather events. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says we have only around 12 years to reduce global carbon emissions to limit temperature rises to 1.5 degrees. While international and national actions are critical, at a local and personal level we need to play our role in achieving that target.”[202]

The declaration by the Auckland City Council also obliges dozens of council committees to include a climate change impact statement in their reports. This has the advantage of keeping diverse teams working for the Council focused on the issue.[207]

Financial justification[]

Financial liability for the damage caused by rising sea levels and climate related disasters will largely fall on city councils. In July 2019, a review of local government funding by the Productivity Commission has found more funding and support is required from central government because of the significant challenges councils are having to face adapting to sea level rise and flooding. The review found that many local councils are frustrated by the lack of leadership from Government; in particular councils want advice, guidance and legal frameworks to support decisions they need to make about land use in areas that are, or will become, prone to flooding."[208]

An example of the difficulties that will likely arise is the decision by National MP, Judith Collins and her husband David Wong-Tung to sue the Nelson City Council for $180,000 for remedial works and lost rental income after a slip damaged their property during heavy rain in Nelson in 2011. At the time the flooding which occurred that day was described as a one in 250 year event.[209] Global warming increases the frequency of such events. Collins is claiming that omissions by the Council caused the landslide which damaged their property. The Council has accepted some of the claims and denied others.[210]

Media commentator, Greg Roughan, points out that as the frequency of such events increases, the cost to business, and councils will only get worse. He also points to the negative impact on property prices if, for example, a low stretch of motorway just north of the Auckland harbour bridge gets washed out multiple times each year, preventing thousands of people from getting to work; and to the legal and financial ramifications if a council grants consent for beachfront properties to be built in an area that a few years later insurers decide not to underwrite. Roughan argues that by declaring a climate emergency, forward-looking Councils are making the point - "this is going to get expensive".[207]

National government[]

In May 2019, Green MP Chlöe Swarbrick requested leave to pass a motion in Parliament declaring a climate emergency. Such a motion requires the unanimous consent of parliament - but was blocked by the National Party. Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern said: "We're not opposed to the idea of declaring [a climate change] emergency in Parliament, because certainly I'd like to think our policies and our approach demonstrates that we do see it as an emergency." Radio New Zealand reports that "the climate change declaration has been signed by 90 percent of the country's mayors and council chairs around New Zealand, and it calls for the government to be ambitious with its climate change mitigation measures".[211] However, on 18 July 2019, youth MPs demonstrated the importance of this issue to young people and "beat their actual MPs to the punch by declaring a climate change emergency at (the triennial) Youth Parliament 2019."[212]

On 14 May 2019, Wellington inhabitant Ollie Langridge began sitting on the lawn outside Parliament holding a sign calling on the Government to declare a climate change emergency.[213] From 28 July, Langridge set a record as the longest running protest outside Parliament in New Zealand's history.[214] Langridge's protest achieved international attention.[215] After protesting outside Parliament every day for 100 days, Langridge cut back his presence to Fridays only, saying he wanted to spend more time with his wife and children.[215]

On 2 December 2020, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern declared a climate change emergency in New Zealand and sponsored a parliamentary motion pledging that the New Zealand Government would aim to be "carbon neutral" by 2025 in line with the goals of the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act. As part of the Government's "carbon neutral" goals, the public sector will be required to buy only electric or hybrid vehicles, government buildings will have to meet new building standards, and all 200 coal-fired boilers in public service buildings will be phased out. This motion was supported by the governing center-left Labour and left-wing Green parties and the opposition Māori Party but was opposed by the centre-right opposition National and libertarian ACT parties.[216][217]

On 14 December 2020, Swedish climate change activist Greta Thunberg criticised the Labour Government's climate change emergency declaration as "virtue signalling," stating that the Government had only committed to reducing less than one percent of New Zealand's carbon emissions by 2025.[218][219] In response, Prime Minister Ardern defended her Government's climate change declaration, stating that New Zealand had bigger goals than one target.[219][220] In addition, Climate Change Minister James Shaw responded that the climate change declaration was only just the "starting point" in New Zealand's climate change response measures.[221]

Opinion polls[]

On 13 June 2019 a 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton poll found that a majority of New Zealanders (53%) believe the Government should declare a climate emergency. 39% said no, and eight % did not know.[222] More than 50 of the country's top researchers have also called on New Zealand politicians to declare a climate emergency. Their appeal to government states: "The scientific consensus is that the world stands on the verge of unprecedented environmental and climate catastrophe for which we are little prepared, and which affords us only a few years for mitigating action. We, the undersigned, urge the New Zealand House of Representatives to declare a climate emergency, now."[223]

Support for national declaration[]

The Labour Party Climate Change manifesto lists one of its goals as "[Making] New Zealand a leader in the international fight against climate change, and in ensuring that the 2015 Paris Agreement is successfully implemented."[224] As at June 2019, four countries have formally declared a climate emergency: the UK, France, Canada and Ireland. (Despite these declarations, these countries still provide subsidies of $27.5bn annually which support fossil fuel industries.)[225] If the Labour Party wants New Zealand to be a world leader in this area, the Government will need to follow or do better than the example set by these four.

Tom Powell of Climate Karanga Marlborough argues that it is only when we recognise we are facing an actual emergency that our local and national governments get away from "business as usual".[226] Greg Roughan agrees arguing that it takes time for 'out there ideas' (such as a climate crisis) to become mainstream so that political action can be implemented. A declaration that there is a climate emergency from a reputable source such as a city council or national government brings "mainstream cred to the need for urgent action - even if it doesn't spell out how that looks."[227]

Climate Change Minister, James Shaw, says "This is obviously not a civil defence emergency, but it creates civil defence emergencies and is increasing civil defence emergencies. It is a meta-emergency. It is quite weird not to call it an emergency, given its consequences."[228] Introducing a "feebate" scheme for car imports in July 2019, associate transport minister, Julie Anne Genter, spoke about fronting up to climate change by comparing it to fighting World War II.[229]

At the Just Transition Community Conference sponsored by the New Plymouth District Council on 15 June 2019,[230] Victoria University professor and keynote speaker, James Renwick, said the situation was dire. He continued: "Last year saw the highest emissions globally on record and emissions have been going up, up and up for the past 30 years. If the world continues to emit greenhouse gasses it will lock in a further 3C of global warming and 10m of sea level rise... There's been a lot of talk about a climate emergency lately and it really is an emergency situation."[231]

Opposed to national declaration[]

The decision by local councils to declare climate emergencies has led to debate in the media about what a declaration of an emergency really means and whether or not such declarations will be backed up by significant action to address the problem.[232][233]

National MP, Paula Bennett, called the Prime Minister "ridiculous" because of her willingness to declare a "climate emergency". Bennett said declarations of emergency should only be used for "very serious events" such as the earthquakes which occurred in Christchurch in 2011.[234] National's climate change spokesman, Todd Muller, says "This is a 30, 40, 50-year, multi-generational transition for the economy away from fossil fuels. It's not an emergency in that context – to say it's an emergency is absolutely ridiculous. When you call something from a government – central or local – an emergency, you are saying you are pursuing this above all else."[228]

See also[]

- Agriculture in New Zealand

- Ara ake National New Energy Development Centre

- Climate Change Commission

- Energy in New Zealand

- Environment of New Zealand

- Generation Zero

- List of countries by greenhouse gas emissions per capita

- New Zealand Climate Science Coalition

- Pollution in New Zealand

References[]

- ^ Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California, U.S.A.

- ^ "Our atmosphere and climate 2017". Ministry for the Environment and Statistics NZ. October 2017.

- ^ a b Climate Change Implications for New Zealand, Royal Society of New Zealand, 19 April 2016, ISBN 978-1-877317-16-3

- ^ "New Zealand's out-sized climate change contribution". Stuff. 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Zero Carbon Bill revealed: everything you need to know". The Spinoff. 8 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "New Zealand's Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990 2017", ME1411, Ministry for the Environment, April 2019

- ^ "Proposed Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Bill". Ministry for the Environment.

- ^ Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern (8 May 2019). "Landmark climate change bill goes to Parliament". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "New Zealand's Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2014" (PDF), ME1195, Ministry for the Environment, May 2016, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2019, retrieved 21 May 2016

- ^ "New Zealand's greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990 – 2016" (PDF). Ministry for the Environment. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Greenhouse gas emissions have barely budged in a decade, new data shows Stuff, 27 June 2019

- ^ Rising NZ emissions sparks call for transport crackdown, NZ Herald 11 April 2019

- ^ New Zealand's GreenhouseGas Inventory 1990–2017 Archived 31 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry for the Environment, Snapshot April 2019

- ^ New Zealand's out-sized climate change contribution, NZ Herald, 8 December 2018

- ^ a b New Zealand’s changing climate and oceans: The impact of human activity and implications for the future, An assessment of the current state of scientific knowledge by the Office of the Chief Science Advisor, July 2013

- ^ Gibson, Eloise (5 December 2009). "Measuring the air that we breathe". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Carbon dioxide, Baring Head, New Zealand, NIWA

- ^ Lowe, David (2006). "The changing composition of the Earth's atmosphere: linkages to increasing agricultural and industrial activity". In Chapman, Ralph; Boston, Jonathan; Schwass, Margot (eds.). Confronting Climate Change. Critical issues for New Zealand. Wellington: Victoria University Press. pp. 75–82.

- ^ Forster, P.; et al. 2.3 Chemically and Radiatively Important Gases. IPCC AR4 WG1 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ IEA (2009). "CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion". Paris: International Energy Association. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Country Data New Zealand". CO2 Scorecard. 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

per capita CO2 emissions of 9.28 metric tons per year, it is in the highest quartile globally

- ^ Bill Allan; Katja Riedel; Richard McKenzie; Sylvia Nichol; Tom Clarkson (2 March 2009). "Atmosphere – Greenhouse gas measurements in New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Methane, NZ Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre

- ^ FutureFeed, CSIRO

- ^ "Greenhouse Gases". University of Waikato. 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ MfE (2007). "State of New Zealand's Environment 1997 – Chapter 10: Conclusions". Ministry for the Environment. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2012.