Cochineal

| Cochineal | |

|---|---|

| |

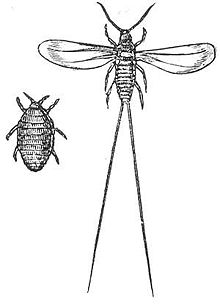

| Female (left) and male (right) cochineals | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia

|

| Phylum: | Arthropoda

|

| Class: | Insecta

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | Dactylopiidae

|

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. coccus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dactylopius coccus Costa, 1835

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Coccus cacti Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The cochineal (/ˌkɒtʃɪˈniːl/ KOTCH-ih-NEEL, /ˈkɒtʃɪniːl/ KOTCH-ih-neel; Dactylopius coccus) is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America through North America (Mexico and the Southwest United States), this insect lives on cacti in the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and nutrients. The insects are found on the pads of prickly pear cacti, collected by brushing them off the plants, and dried.

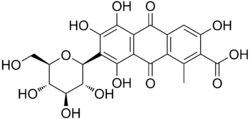

The insect produces carminic acid that deters predation by other insects. Carminic acid, typically 17-24% of dried insects' weight, can be extracted from the body and eggs, then mixed with aluminium or calcium salts to make carmine dye, also known as cochineal. Today, carmine is primarily used as a colorant in food and in lipstick (E120 or Natural Red 4).

The carmine dye was used in North America in the 15th century for coloring fabrics and became an important export good during the colonial period. After synthetic pigments and dyes such as alizarin were invented in the late 19th century, natural-dye production gradually diminished. Health fears over artificial food additives, however, have renewed the popularity of cochineal dyes, and the increased demand has made cultivation of the insect profitable again,[1] with Peru being the largest exporter. Some towns in the Mexican state of Oaxaca are still working in handmade textiles using this cochineal.[2]

Other species in the genus Dactylopius can be used to produce "cochineal extract", and are extremely difficult to distinguish from D. coccus, even for expert taxonomists; that scientific term from the binary nomenclature, and also the vernacular "cochineal insect", may be used (whether intentionally or casually, and whether or not with misleading effect) to refer to other biological species.[note 1]

Etymology[]

Cochineal is derived from the French "cochenille", derived from Spanish "cochinilla", in turn derived from Latin "coccinus" meaning "scarlet-colored", or from the Latin "coccum", meaning "berry yielding scarlet dye". See also the related word kermes, which is the source of a similar but weaker Mediterranean dye also called crimson, which was used to color cloth red before discovery of cochineal in the New World. Some sources identify the Spanish source word for cochineal as cochinilla "wood louse" (a diminutive form of Spanish cochino, cognate with French cochon, meaning "pig")."[3]

History[]

Cochineal dye was used by the Aztec and Maya peoples of North and Central America as early as the second century BC.[4] Eleven cities conquered by Montezuma in the 15th century paid a yearly tribute of 2000 decorated cotton blankets and 40 bags of cochineal dye each.[5] Production of cochineal is depicted in Codex Osuna. During the colonial period, the production of cochineal (grana fina) grew rapidly.[6] Produced almost exclusively in Oaxaca by indigenous producers, cochineal became Mexico's second-most valued export after silver.[7] Soon after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, it began to be exported to Spain, and by the 17th century was a commodity traded as far away as India.[8] The dyestuff was consumed throughout Europe and was so highly prized, its price was regularly quoted on the London and Amsterdam Commodity Exchanges (with the latter one beginning to record it in 1589).[6] In 1777, French botanist Nicolas-Joseph Thiéry de Menonville, presenting himself as a botanizing physician, smuggled the insects and pads of the Opuntia cactus to Saint Domingue. This particular collection failed to thrive and ultimately died out, leaving the Mexican monopoly intact.[9] After the Mexican War of Independence in 1810–1821, the Mexican monopoly on cochineal came to an end. Large-scale production of cochineal emerged, especially in Guatemala and the Canary Islands; it was also cultivated in Spain and North Africa.[8]

Spain's conquest of a New World empire in the 16th century introduced new pigments and colors to peoples on both sides of the Atlantic. Carmine, a dye and pigment derived from cochineal insects in Central and South America, attained great status and value in Europe. Produced from harvested, dried, and crushed cochineal insects, carmine could be (and still is) used in fabric dye, food dye, body paint, or almost any kind of paint or cosmetic.[citation needed]

The Florentine Codex contains a variety of illustrations with multiple variations of the red pigments. Specifically in the case of achiotl (light red), technical analysis of the paint reveals multiple layers of the pigment although the layers of the pigment is not visible to the naked eye. Therefore, it proves that the process of applying multiple layers is more significant in comparison to the actual color itself. Furthermore, the process of layering the various hues of the same pigment on top of each other enabled the Aztec artists to create variations in the intensity of the subject matter. A bolder application of pigment draws the viewer's eye to the subject matter which commands attention and suggests a power of the viewer. A weaker application of pigment commands less attention and has less power. This would suggest that the Aztec associated the intensity of pigments with the idea of power and life.[10]

Natives of Peru had been producing cochineal dyes for textiles since at least 700 CE, but Europeans had never seen the color before. When the Spanish invaded the Aztec empire in what is now Mexico, they were quick to exploit the color for new trade opportunities. Carmine became the region's second-most-valuable export next to silver. Pigments produced from the cochineal insect gave the Catholic cardinals their vibrant robes and the English "Redcoats" their distinctive uniforms. That an insect was the true source of the pigment was kept secret until the 18th century, when biologists discovered the source.[11]

The demand for cochineal fell sharply with the appearance on the market of alizarin crimson and many other artificial dyes discovered in Europe in the middle of the 19th century, causing a significant financial shock in Spain as a major industry almost ceased to exist.[7] The delicate manual labour required for the breeding of the insect could not compete with the modern methods of the new industry, and even less so with the lowering of production costs. The "tuna blood" dye (from the Mexican name for the Opuntia fruit) stopped being used and trade in cochineal almost totally disappeared in the course of the 20th century. In recent decades, the breeding of cochineal has been done mainly for the purposes of maintaining the tradition rather than to satisfy any sort of demand.[12] However, the product has become commercially valuable again.[13] One reason for its popularity is that many commercial synthetic red dyes and food colorings have been found to be carcinogenic.[14]

Art[]

The carmine of antiquity (technically, crimson) also contains carminic acid, and was extracted from a similar insect, Kermes vermilio, which lives on Quercus coccifera oaks native to the Near East, and the European side of the Mediterranean Basin. Kermes extract was used as a dye and a laked pigment in ancient Egypt, Greece, Armenia and the Near East and is one of the oldest organic pigments.[15] Recipes for artists' use of crimson appear in many early painting and alchemical handbooks throughout the Middle Ages; the laking process for both crimson and carmine was improved in the 19th century. Carmine was not light-fast and was largely abandoned in art.[16] True carmine, when it was introduced later, saw its primary use in Europe as a dye rather than a pigment.

Spanish influence changed the way in which Aztecs used pigments, particularly in their manuscripts. For example, cochineal was replaced by Spanish dyes like minium and alizarin crimson.[17] The image of Moctezuma's death (seen to the right) uses both indigenous and Spanish pigments, and is therefore representative of the transition and influence between cultures.[citation needed]

Biology[]

Cochineal insects are soft-bodied, flat, oval-shaped scale insects. The females, wingless and about 5 mm (0.20 in) long, cluster on cactus pads. They penetrate the cactus with their beak-like mouthparts and feed on its juices, remaining immobile unless alarmed. After mating, the fertilised female increases in size and gives birth to tiny nymphs. The nymphs secrete a waxy white substance over their bodies for protection from water loss and excessive sun. This substance makes the cochineal insect appear white or grey from the outside, though the body of the insect and its nymphs produces the red pigment, which makes the insides of the insect look dark purple. Adult males can be distinguished from females in that males have wings, and are much smaller.[18]

The cochineal disperses in the first nymph stage, called the "crawler" stage. The juveniles move to a feeding spot and produce long wax filaments. Later, they move to the edge of the cactus pad, where the wind catches the wax filaments and carries the insects to a new host. These individuals establish feeding sites on the new host and produce a new generation of cochineals.[19] Male nymphs feed on the cactus until they reach sexual maturity. At this time, they can no longer feed at all and live only long enough to fertilise the eggs.[20] They are, therefore, seldom observed.[19] In addition, females typically outnumber males due to environmental factors.[21]

Host cacti[]

Dactylopius coccus is native to tropical and subtropical South America and North America in Mexico, where their host cacti grow natively. They have been widely introduced to many regions where their host cacti also grow. About 200 species of Opuntia cacti are known, and while it is possible to cultivate cochineal on almost all of them, the most common is Opuntia ficus-indica.[22] D. coccus has only been noted on Opuntia species, including O. amyclaea, O. atropes, O. cantabrigiensis, O. brasilienis, O. ficus-indica, O. fuliginosa, O. jaliscana, O. leucotricha, O. lindheimeri, O. microdasys, O. megacantha, O. pilifera, O. robusta, O. sarca, O. schikendantzii, O. stricta, O. streptacantha, and O. tomentosa.[1] Feeding cochineals can damage and kill the plant. Other cochineal species feed on many of the same Opuntia, and the wide range of hosts reported for D. coccus likely is because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other Dactylopius species.[23]

Farming[]

A nopal cactus farm for the production of cochineal is traditionally known as a nopalry.[24] The two methods of farming cochineal are traditional and controlled. Cochineals are farmed in the traditional method by planting infected cactus pads or infesting existing cacti with cochineals and harvesting the insects by hand. The controlled method uses small baskets called Zapotec nests placed on host cacti. The baskets contain clean, fertile females that leave the nests and settle on the cactus to await fertilization by the males. In both cases, the cochineals must be protected from predation, cold, and rain. The complete cycle lasts three months, during which time the cacti are kept at a constant temperature of 27 °C (81 °F). At the end of the cycle, the new cochineals are left to reproduce or are collected and dried for dye production.[22]

To produce dye from cochineals, the insects are collected when they are around 90 days old. Harvesting the insects is labour-intensive, as they must be individually knocked, brushed, or picked from the cacti and placed into bags. The insects are gathered by small groups of collectors who sell them to local processors or exporters.[25]

Several natural enemies can reduce the population of the insects on hosts. Of all the predators, insects seem to be the most important group. Insects and their larvae such as pyralid moths (order Lepidoptera), which destroy the cactus, and predators such as lady bugs (Coleoptera), various Diptera (such as Syrphidae and Chamaemyiidae), lacewings (Neuroptera), and ants (Hymenoptera) have been identified, as well as numerous parasitic wasps. Many birds, human-commensal rodents (especially rats) and reptiles also prey on cochineal insects. In regions dependent on cochineal production, pest control measures are taken seriously. For small-scale cultivation, manual methods of control have proved to be the safest and most effective. For large-scale cultivation, advanced pest control methods have to be developed, including alternative bioinsecticides or traps with pheromones.[1]

Farming in Australia[]

Opuntia species, known commonly as prickly pears, were first brought to Australia in an attempt to start a cochineal dye industry in 1788. Captain Arthur Phillip collected a number of cochineal-infested plants from Brazil on his way to establish the first European settlement at Botany Bay, part of which is now Sydney, New South Wales. At that time, Spain and Portugal had a worldwide cochineal dye monopoly via their New World colonial sources, and the British desired a source under their own control, as the dye was important to their clothing and garment industries; it was used to color the British soldiers' red coats, for example.[26] The attempt was a failure in two ways: the Brazilian cochineal insects soon died off, but the cactus thrived, eventually overrunning about 100,000 sq mi (259,000 km2) of eastern Australia.[27] The cacti were eventually brought under control in the 1920s by the deliberate introduction of a South American moth, Cactoblastis cactorum, the larvae of which feed on the cactus.[27]

Farming in Ethiopia[]

The nopal pear has been traditionally eaten in parts of northern Ethiopia, where it is utilized more than cultivated. Carmine cochineal was introduced into northern Ethiopia early in the 2000s to be cultivated among farming communities. Foodsafe exported 2000 tons of dried carmine cochineal over 3 years.[citation needed]

A conflict of interest among communities led to closure of the cochineal business in Ethiopia, but the insect spread and became a pest. Cochineal infestation continued to expand after the cochineal business had ended. Control measures were unsuccessful and by 2014 about 16,000 hectares (62 sq mi) of cactus land had become infested with cochineal.[28]

Dye[]

Carminic acid is extracted from the female cochineal insects and is treated to produce carmine, which can yield shades of red such as crimson and scarlet. The body of the insect is 19–22% carminic acid.[13] The insects are processed by immersion in hot water or exposure to sunlight, steam, or the heat of an oven. Each method produces a different color that results in the varied appearance of commercial cochineal. The insects must be dried to about 30% of their original body weight before they can be stored without decaying.[25] It takes about 80,000 to 100,000 insects to make one kilogram of cochineal dye.[29]

The two principal forms of cochineal dye are cochineal extract, a coloring made from the raw dried and pulverised bodies of insects, and carmine, a more purified coloring made from the cochineal. To prepare carmine, the powdered insect bodies are boiled in ammonia or a sodium carbonate solution, the insoluble matter is removed by filtering, and alum is added to the clear salt solution of carminic acid to precipitate the red aluminium salt. Purity of color is ensured by the absence of iron. Stannous chloride, citric acid, borax, or gelatin may be added to regulate the formation of the precipitate. For shades of purple, lime is added to the alum.[5]

As of 2005,[needs update] Peru produced 200 tons of cochineal dye per year and the Canary Islands produced 20 tons per year.[13][25] Chile and Mexico also export cochineal.[1] In Mexico, production and exportation of the dye has been found to lower poverty and improve female literacy.[30] France is believed to be the world's largest importer, and Japan and Italy also import the insect. Much of these imports are processed and re-exported to other developed economies.[25] As of 2005,[needs update] the market price of cochineal was between US$50 and 80 per kilogram,[needs update][22] while synthetic raw food dyes are available at prices as low as $10–20 per kilogram.[31]

Uses[]

Traditionally, cochineal was used for coloring fabrics. During the colonial period, with the introduction of sheep to Latin America, the use of cochineal increased, as it provided the most intense color and it set more firmly on woolen garments than on clothes made of materials of pre-Hispanic origin such as cotton or agave and yucca fibers. In general, cochineal is more successful on protein-based animal fibres (including silk) than plant-based material. Once the European market discovered the qualities of this product, the demand for it increased dramatically. By the beginning of the 17th century, it was traded internationally.[8] Carmine became strong competition for other colorants such as madder root, kermes, Polish cochineal, Armenian cochineal, brazilwood, and Tyrian purple,[32] as they were used for dyeing the clothes of kings, nobles, and the clergy. For the past several centuries, it was the most important insect dye used in the production of hand-woven oriental rugs, almost completely displacing lac.[8] It was also used for painting, handicrafts, and tapestries.[12] Cochineal-colored wool and cotton are important materials for Mexican folk art and crafts.[33][34]

Cochineal is used as a fabric and cosmetics dye and as a natural food coloring. It is also used in histology as a preparatory stain for the examination of tissues and carbohydrates.[35] In artists' paints, it has been replaced by synthetic reds and is largely unavailable for purchase due to poor lightfastness. Natural carmine dye used in food and cosmetics can render the product unacceptable to vegetarian or vegan consumers. Many Muslims consider carmine-containing food forbidden (haraam) because the dye is extracted from insects and all insects except the locust are haraam in Islam.[36] Jews also avoid food containing this additive, though it is not treif, and some authorities allow its use because the insect is dried and reduced to powder.[37]

Cochineal is one of the few water-soluble colorants to resist degradation with time. It is one of the most light- and heat-stable and oxidation-resistant of all the natural organic colorants and is even more stable than many synthetic food colors.[38] The water-soluble form is used in alcoholic drinks with calcium carmine; the insoluble form is used in a wide variety of products. Together with ammonium carmine, they can be found in meat, sausages, processed poultry products (meat products cannot be colored in the United States unless they are labeled as such), surimi, marinades, alcoholic drinks, bakery products and toppings, cookies, desserts, icings, pie fillings, jams, preserves, gelatin desserts, juice beverages, varieties of cheddar cheese and other dairy products, sauces, and sweets.[38]

Carmine is considered safe enough for cosmetic use in the eye area.[39] A significant proportion of the insoluble carmine pigment produced is used in the cosmetics industry for hair- and skin-care products, lipsticks, face powders, rouges, and blushes.[38] A bright red dye and the stain carmine used in microbiology is often made from the carmine extract, too.[20] The pharmaceutical industry uses cochineal to color pills and ointments.[25]

Risks and labeling[]

In spite of the widespread use of carmine-based dyes in food and cosmetic products, a small number of people have been found to experience occupational asthma, food allergy and cosmetic allergies (such as allergic rhinitis and cheilitis), IgE-mediated respiratory hypersensitivity, and in rare cases anaphylactic shock.[40][41][42] In 2009 the FDA ruled that labels of cosmetics and food that include cochineal extract must include that information on their labels (under the name "cochineal extract" or "carmine").[43][44] In 2006 the FDA stated it found no evidence of a "significant hazard" to the general population.[45] In the EU authorities list carmine as additive E 120 in the list of EU-approved food additives.[46] An artificial, non-allergenic cochineal dye is labeled E 124.[40] The directive governing food dyes approves the use of carmine for certain groups of foods only, but is still found in several products particularly alcoholic beverages.[citation needed]

Notes[]

- ^ The primary biological distinctions between species are minor differences in host plant preferences, along with very different geographic distributions.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Liberato Portillo M.; Ana Lilia Vigueras G. "Natural Enemies of Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus Costa): Importance in Mexico" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- ^ Natural Dyeing in Mexico

- ^ "Cochineal". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 141. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Threads In Tyme, LTD. "Time line of fabrics". Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dr. Aguilar, Moreno (2006). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Los Angeles: California State University. pp. 344. ISBN 0-8160-5673-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Behan, J. "The bug that changed history". Archived from the original on June 21, 2006. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Eiland & Eiland 1998, p. 55.

- ^ Schiebinger 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Magaloni Kerpel, Diana (2014). The Colors of The New World. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Research Institute. pp. 35–40.

- ^ Amy Butler Greenfield (26 April 2005). A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-052275-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hernández, O. "Cochineal". Mexico Desconocido Online. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Canary Islands cochineal producers homepage". Archived from the original on June 24, 2005. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- ^ Schiebinger 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Whitney, Alyson V.; Van Duyne, Richard P.; Casadio, Francesca (2006). "An innovative surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) method for the identification of six historical red lakes and dyestuffs". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 37 (10): 993–1002. Bibcode:2006JRSp...37..993W. doi:10.1002/jrs.1576.

- ^ Magaloni Kerpel, Diana (2014). The Colors of the New World: Artists, Materials, and the Creation of the Florentine Codex. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Research Institute. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-60606-329-3.

- ^ Eisner, T. (2003). For Love of Insects. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01827-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olson, C. "Cochineal". Urban Integrated Pest Management. Archived from the original on November 19, 2005. Retrieved July 19, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Armstrong, W. P. "Cochineal, Saffron & Woad Photos". Economic Plant Photographs. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- ^ Nobel, P. S. (2002). Cacti: Biology and Uses. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-520-23157-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Cultivation of Cochineal in Oaxaca". Go-Oaxaca Newsletter. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2005.

- ^ Ferris, G. Floyd (1955). Atlas of the Scale Insects of North America, Volume VII. Stanford University Press. pp. 85–90. ISBN 0-8047-1667-6.

- ^ "definition of nopalry from Webster Dictionary. Accessed Nov. 4, 2009". Webster-dictionary.net. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Foodnet. "Tropical commodities and their markets". Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- ^ "Prickly Pear in Australia". Northwestweeds.nsw.gov.au. June 26, 1987. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenfield 2005, p. 188.

- ^ Tesfay Belay Reda. 2014. Cactus Pear & Carmine Cochineal: introduction & use in Ethiopia. Lambert Academic Publishing.[page needed]

- ^ "Cochineal and Carmine". Major colorants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Diaz-Cayeros, Alberto; Jha, Saumitra (2012). "Contracts and Poverty Alleviation in Indigenous Communities: Cochineal in Mexico" (PDF). Global Trade.

- ^ "Price Quote". Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2005.

- ^ Meyer, L. "Dyeing Red". West Kingdom (SCA) Arts and Sciences Tourney, July 2004. Archived from the original on February 2, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2005.

- ^ Wood, W. W. (2008). Made in Mexico: Zapotec weavers and the global ethnic art market. Indiana University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Phipps, E. (2010). Cochineal red: the art history of a color. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[page needed]

- ^ Athens, G.A. "Dazzling Color in the Land of the Inca: A Centuries-old Dye Still Important in Histology Today" (PDF). Histologic. XLVI (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-16.

- ^ "E-Numbers List: Cochineal / Carminic Acid". Muslim Consumer Group. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Pischei Teshuvah Yoreh Deah 87-20

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wild Flavors, Inc. "E120 Cochineal". The wild world of solutions. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2005.

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (June 9, 2015). "Summary of Color Additives for Use in United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices". Silver Spring, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Voltolini S, Pellegrini S, Contatore M, Bignardi D, Minale P (2014). "New risks from ancient food dyes: cochineal red allergy" (PDF). European Annals of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 46 (6): 232–3. PMID 25398168.

- ^ D'Mello, J. P. Felix (2003). Food Safety: Contaminants and Toxins. Wallingford, Oxon: CABI Pub. p. 256. ISBN 0-85199-607-8.

- ^ DiCello, Michael C.; Myc, Andrzej; Baker, James R.; Baldwin, James L. (1999). "Anaphylaxis After Ingestion of Carmine Colored Foods: Two Case Reports and a Review of the Literature". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 20 (6): 377–82. doi:10.2500/108854199778251816. PMID 10624494.

- ^ FDA. Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine: Declaration by Name on the Label of All Foods and Cosmetic Products That Contain These Color Additives; Small Entity Compliance Guide. Silver Spring, MD:U.S. Food & Drug Administration (updated June 7, 2011). [accessed July 16, 2015].

- ^ "Bug-Based Food Dye Should Be ... Exterminated, Says CSPI". Center for Science in the Public Interest. May 1, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "FDA: You're eating crushed bug juice". Archived from the original on February 10, 2006.

- ^ "Food Standards Agency – Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Food.gov.uk. March 14, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

Further reading[]

- Baskes, Jeremy (2000). Indians, Merchants and Markets: A Reinterpretation of the Repartimiento and Spanish-Indian Economic Relations in Colonial Oaxaca, 1750–1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3512-3.

- Donkin, R. A. (1977). "Spanish Red: An Ethnogeographical Study of Cochineal and the Opuntia Cactus". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 67 (5): 1–84. doi:10.2307/1006195. JSTOR 1006195.

- Eiland, Murray L. Jr. & Eiland, Murray L., III (1998). Oriental Carpets. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-8212-2548-0.

- Greenfield, Amy Butler (2005). A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire. New York: Harper Collins Press. ISBN 0-06-052276-3.

- Hamnett, Brian (1971). Politics and Trade in Southern Mexico, 1750–1821. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07860-1.

- McCreery, David (1996). Rural Guatemala 1760–1940. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2792-9.

- Schiebinger, L. L. (2004). Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01487-1.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cochineal. |

| Look up cochineal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Dactylopius coccus. |

- Felter, Harvey Wickes; Lloyd, John Uri (1898). "Coccus (U.S.P.)—Cochineal". King's American Dispensatory. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- Direction of the Council of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (1911). "Coccus, B.P." The British Pharmaceutical Codex. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- Sayre, Lucius E. (1917). "Coccus.—Cochineal". A Manual of Organic Materia Medica and Pharmacognosy. Retrieved July 14, 2005.

- Zhang, Jane (January 27, 2006). "Is There a Bug in Your Juice? New Food Labels Might Say". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009.

- Greig, J. B. "Cochineal extract, carmine, and carminic acid". WHO food additive series 46. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Dutton, LaVerne M. "Cochineal: A Bright Red Animal Dye". Master's Thesis for Baylor University. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- Insects described in 1835

- Taxa named by Oronzio Gabriele Costa

- Pigments

- Animal dyes

- Food colorings

- Food science

- Scale insects

- Insects as food

- E-number additives