Colonization

Colonization, or colonisation refers to large-scale population movements where the migrants maintain strong links with their or their ancestors' former country, gaining significant privileges over other inhabitants of the territory by such links. When colonization takes place under the protection of colonial structures, it may be termed settler colonialism. This often involves the settlers dispossessing indigenous inhabitants, or instituting legal and other structures which systematically disadvantage them.[1]

In its basic sense, colonization can be defined as the process of establishing foreign control over target territories or people for the purpose of cultivation, often through establishing colonies and possibly by settling them.[2]

In colonies established by Western European countries in the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, settlers (supplemented by Central European, Eastern European, Asian and African people) eventually formed a large majority of the population after killing, assimilating or driving away indigenous peoples.

In other places, Western European settlers formed minority groups, often dominating the non-Western European majority.[3]

During the European colonization of Australia, New Zealand and other places in Oceania, explorers and colonists often regarded the landmasses as terra nullius, meaning "empty land" in Latin.[4] Owing to the absence of Western farming techniques, Europeans deemed the land unaltered by mankind and therefore treated it as uninhabited, despite the presence of indigenous populations. In the 19th century, laws and ideas such as Mexico's General Colonization Law and the United States' manifest destiny doctrine encouraged further colonization of the Americas, already started in the 15th century.

Lexicology[]

The term colonization is derived from the Latin words colere ("to cultivate, to till"),[5] colonia ("a landed estate", "a farm") and colonus ("a tiller of the soil", "a farmer"),[6] then by extension "to inhabit".[7] Someone who engages in colonization, i.e. the agent noun, is referred to as a colonizer, while the person who gets colonized, i.e. the object of the agent noun or absolutive, is referred to as a colonizee,[8] colonisee or the colonised.[9]

Pre-modern colonizations[]

Classical period[]

In ancient times, maritime nations such as the city-states of Greece and Phoenicia often established colonies to farm what they believed was uninhabited land. Land suitable for farming was often occupied by migratory 'barbarian tribes' who lived by hunting and gathering. To ancient Greeks and Phoenicians, these lands were regarded as simply vacant.[citation needed] However, this did not mean that conflict did not exist between the colonizers and local/native peoples. Greeks and Phoenicians also established colonies with the intent of regulating and expanding trade throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East.

Another period of colonization in ancient times was during the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire conquered large parts of Western Europe, North Africa and West Asia. In North Africa and West Asia, the Romans often conquered what they regarded as 'civilized' peoples. As they moved north into Europe, they mostly encountered rural peoples/tribes with very little in the way of cities. In these areas, waves of Roman colonization often followed the conquest of the areas. Many of the current cities throughout Europe began as Roman colonies, such as Cologne, Germany, originally called Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium by the Romans, and the British capital city of London, which the Romans founded as Londinium.

Middle Ages[]

The decline and collapse of the Roman Empire saw (and was partly caused by) the large-scale movement of people in Eastern Europe and Asia. This is largely seen as beginning with nomadic horsemen from Asia (specifically the Huns) moving into the richer pasture land to the west, thus forcing the local people there to move further west and so on until eventually the Goths were forced to cross into the Roman Empire, resulting in continuous war with Rome which played a major role in the fall of the Roman Empire. During this period there were large-scale movements of peoples establishing new colonies all over western Europe. The events of this time saw the development of many of the modern-day nations of Europe like the Franks in France and Germany and the Anglo-Saxons in England.

In West Asia, during Sassanid Empire, some Persians established colonies in Yemen and Oman. The Arabs also established colonies in Northern Africa, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, and remain the dominant majority to this day.[10][11][12][13][14]

The Vikings of Scandinavia also carried out a large-scale colonization. The Vikings are best known as raiders, setting out from their original homelands in Denmark, southern Norway and southern Sweden, to pillage the coastlines of northern Europe. In time, the Vikings began trading and established colonies. The Vikings discovered Iceland and established colonies before moving onto Greenland, where they briefly held some colonies. The Vikings launched an unsuccessful attempt at colonizing an area they called Vinland, which is probably at a site now known as L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador, on the eastern coastline of Canada.

Modern colonialism[]

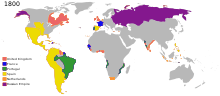

In the Colonial Era, colonialism in this context refers mostly to Western European countries' colonization of lands mainly in the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania. The main European countries active in this form of colonization included Spain, Portugal, France, the Kingdom of England (later Great Britain), the Netherlands, and the Kingdom of Prussia (now mostly Germany), and, beginning in the 18th century, the United States. Most of these countries had a period of almost complete power in world trade at some stage in the period from roughly 1500 to 1900. Beginning in the late 19th century, Imperial Japan also engaged in settler colonization, most notably in Hokkaido and Korea.

While many European colonization schemes focused on shorter-term exploitation of economic opportunities (Newfoundland, for example, or Siberia) or addressed specific goals (Massachusetts or New South Wales), a tradition developed of careful long-term social and economic planning for both parties, but more on the colonizing countries themselves, based on elaborate theory-building (note James Oglethorpe's Colony of Georgia in the 1730s and Edward Gibbon Wakefield's New Zealand Company in the 1840s).[15]

Colonization may be used as a method of absorbing and assimilating foreign people into the culture of the imperial country, and thus destroying any remnant of the cultures that might threaten the imperial territory over the long term by inspiring reform. The main instrument to this end is linguistic imperialism, or the imposition of non-indigenous imperial (colonial) languages on the colonized populations to the exclusion of any indigenous languages from administrative (and often, any public) use.[16]

Post-colonial variants[]

Russia[]

The Soviet regime in the 1920s tried to win the trust of non-Russians by promoting their ethnic cultures and establishing for them many of the characteristic institutional forms of the nation-state.[17] The early Soviet regime was hostile to even voluntary assimilation, and tried to derussify assimilated non-Russians.[18] Parents and students not interested in the promotion of their national languages were labeled as displaying "abnormal attitudes". The authorities concluded that minorities unaware of their ethnicities had to be subjected to Belarusization, Yiddishization, Polonization etc.[19]

By the early 1930s this extreme multiculturalist policy proved unworkable and the Soviet regime introduced a limited russification[20] for practical reasons; voluntary assimilation, which was often a popular demand,[21] was allowed. The list of nationalities was reduced from 172 in 1927 to 98 in 1939[22] by revoking support for small nations in order to merge them into bigger ones. For example, Abkhazia was merged into Georgia and thousands of ethnic Georgians were sent to Abkhazia.[23] The Abkhaz alphabet was changed to a Georgian base, Abkhazian schools were closed and replaced with Georgian schools, the Abkhaz language was banned.[24] The ruling elite was purged of ethnic Abkhaz and by 1952 over 80% of the 228 top party and government officials and enterprise managers in Abkhazia were ethnic Georgians (there remained 34 Abkhaz, 7 Russians and 3 Armenians in these positions).[25] For Königsberg area of East Prussia (modern Kaliningrad Oblast) given to the Soviet Union at the 1945 Potsdam Conference Soviet control meant a forcible expulsion of the remaining German population and mostly involuntary resettlement of the area with Soviet civilians.[26]

Russians were now presented as the most advanced and least chauvinist people of the Soviet Union.[20]

Baltic states[]

Large numbers of ethnic Russians and other Russian speakers were sent to colonize the Baltic states after their reoccupation in 1944, while local languages, religions and customs were banned or suppressed.[27] David Chioni Moore classified it as a "reverse-cultural colonization", where the colonized perceive the colonizers as culturally inferior.[28] Colonization of the Baltic states was closely tied to mass executions, deportations and repression of the native population. During both Soviet occupations (1940–1941; 1944–1952) a combined 605,000 people in the Baltic states were either killed or deported (135,000 Estonians, 170,000 Latvians and 320,000 Lithuanians), while their properties and personal belongings, along with ones who fled the country, were confiscated and given to the arriving colonists – Soviet military, NKVD personnel, Communist functionaries and economic refugees from kolkhozs.[29]

The most dramatic case was Latvia, where the amount of ethnic Russians swelled from 168,300 (8.8%) in 1935 to 905,500 (34%) in 1989, whereas the proportion of Latvians fell from 77% in 1935 to 52% in 1989.[30] Baltic states also faced intense economic exploitation, with Latvian SSR, for example, transferring 15.961 billion rubles (or 18.8% percent of its total revenue of 85 billion rubles) more to the USSR budget from 1946 to 1990 than it received back. And of the money transferred back, a disproportionate amount was spent on the region's militarization and funding repressive institutions, especially in the early years of the occupation.[31] It has been calculated by a Latvian state-funded commission that the Soviet occupation cost the economy of Latvia a total of 185 billion euros.[32]

Conversely, political economist and world-systems and analyst Samir Amin asserts that, in contrast to colonialism, capital transfer in the USSR was used not to enrich a metropole but to develop poorer regions in the South and East. The wealthiest regions like Western Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic Republics were the main source of capital.[33]

Jewish oblast[]

In 1934, the Soviet government established the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in the Soviet Far East to create a homeland for the Jewish people. Another motive was to strengthen Soviet presence along the vulnerable eastern border. The region was often infiltrated by the Chinese; in 1927, Chiang Kai-shek had ended cooperation with the Chinese Communist Party, which further increased the threat. Fascist Japan also seemed willing and ready to detach the Far Eastern provinces from the USSR.[34] To make settlement of the inhospitable and undeveloped region more enticing, the Soviet government allowed private ownership of land. This led to many non-Jews to settle in the oblast to get a free farm.[35]

By the 1930s, a massive propaganda campaign developed to induce more Jewish settlers to move there. In one instance, a government-produced Yiddish film called Seekers of Happiness told the story of a Jewish family that fled the Great Depression in the United States to make a new life for itself in Birobidzhan. Some 1,200 non-Soviet Jews chose to settle in Birobidzhan.[36] The Jewish population peaked in 1948 at around 30,000, about one-quarter of the region's population. By 2010, according to data provided by the Russian Census Bureau, there were only 1,628 people of Jewish descent remaining in the JAO (1% of the total population), while ethnic Russians made up 92.7% of the JAO population.[37] The JAO is Russia's only autonomous oblast[38] and, aside of Israel, the world's only Jewish territory with an official status.[39]

Israel[]

According to , in his book "Israel's Colonial Project in Palestine: Brutal Pursuit", Israeli settlements in the West Bank may be considered an additional form of colonization.[40] This view is part of a key debate in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.

Indonesia[]

The transmigration program is an initiative of the Indonesian government to move landless people from densely populated areas of Java, but also to a lesser extent from Bali and Madura, to less populous areas of the country including Papua, Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Sulawesi.[41]

Papua New Guinea[]

In 1884 Britain declared a protective order over South East New Guinea, establishing an official colony in 1888. Germany however, annexed parts of the North. This annexation separated the entire region into the South, known as "British New Guinea" and North, known as "Papua".[42]

Philippines[]

Due to marginalisation produced by continuous Resettlement Policy, by 1969, political tensions and open hostilities developed between the Government of the Philippines and Moro Muslim rebel groups in Mindanao.[43][failed verification]

Myanmar[]

Subject peoples[]

Many colonists came to colonies for slaves to their colonizing countries, so the legal power to leave or remain may not be the issue so much as the actual presence of the people in the new country. This left the indigenous natives of their lands slaves in their own countries.

The Canadian Indian residential school system was identified by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Canada) as colonization through depriving the youth of First Nations in Canada of their languages and cultures.[44]

During the mid 20th century, there was the most dramatic and devastating attempt at colonization, and that was pursued with Nazism.[45] Hitler and Heinrich Himmler and their supporters schemed for a mass migration of Germans to Eastern Europe, where some of the Germans were to become colonists, having control over the native people.[45] These indigenous people were planned to be reduced to slaves or wholly annihilated.[45]

Many advanced nations currently have large numbers of guest workers/temporary work visa holders who are brought in to do seasonal work such as harvesting or to do low-paid manual labor. Guest workers or contractors have a lower status than workers with visas, because guest workers can be removed at any time for any reason.

Endo-colonization[]

Colonization may be a domestic strategy when there is a widespread security threat within a nation and weapons are turned inward, as noted by Paul Virilio:

- Obsession with security results in the endo-colonization of society: endo-colonization is the use of increasingly powerful and ubiquitous technologies of security turned inward, to attempt to secure the fast and messy circulations of our globalizing, networked society…it is the increasing domination of public life with stories of dangerous otherness and suspicion…[46]

Some instances of the burden of endo-colonization have been noted:

- The acute difficulties of the Latin American and southern European military-bureaucratic dictatorships in the seventies and early eighties and the Soviet Union in the late eighties can in large part be attributed to the economic, political and social contradictions induced by endo-colonizing militarism.[47]

Space colonization[]

There has been a continued interest and advocation for space colonization. Space colonization has been criticized as unreflected continuation of settler colonialism and manifest destiny, continuing the narrative of colonial exploration as fundamental to the assumed human nature.[48][49][50]

See also[]

- Colonization

- Colonialism

- Coloniality of gender

- Colonization of Antarctica

- Cocacolonization

- Ocean colonization

- List of colonial empires

- Other related

- Colonisation (biology)

- Human settlement

- Imperialism

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

Notes and references[]

- ^ Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire: A Very Short Introduction. United States: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191604447.

- ^ Marc Ferro (1997). COLONIZATION: A GLOBAL HISTORY. Routledge. p. 1. doi:10.4324/9780203992586."Colonization is associated with the occupation of a foreign land, with its being brought under cultivation, with the settlement of colonists. If this definition of the term “colony” is used, the phenomenon dates from the Greek period. Likewise we speak of Athenian, then Roman 'imperialism'."

- ^ Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire: A Very Short Introduction. United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 21–31.

- ^ Painter, Joe; Jeffrey, Alex (2009). Political Geography. London, GBR: SAGE Publications Ltd. p. 169.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0). Oxford University Press. 2009.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis; Charles Scott (1879). A Latin Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Marcy Rockman; James Steele (2003). The Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25606-2.

- ^ Riordan, John P. STAFF COLL FORT LEAVENWORTH KS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED MILITARY STUDIES, 2008.

- ^ Freeman, Luke. "Lesley A. Sharp. The Sacrificed Generation: Youth, History, and the Colonized Mind in Madagascar. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. xvii+ 377 pp. Photographs. Maps. Appendixes. Glossary. Notes. Bibliography. Index. $65.00. Cloth. $27.50. Paper." African Studies Review 46.2 (2003): 106-108.

- ^ Pact Of Umar http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e1803

- ^ North Africa Jamil Abun-Nasr-Michael Brett - https://www.britannica.com/place/North-Africa/From-the-Arab-conquest-to-1830

- ^ Select Spread Of Islam, The http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t253/e17

- ^ the Middle East Kingdoms Kessler - http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsMiddEast/ArabicSyria.htm

- ^ "At the Prophet’s death, according to the Muslim historians, the religion that he had brought was still confined to parts of the Arabian Peninsula. The Arabs, to whom he had brought it, were similarly restricted, with perhaps some extension in the borderlands of the Fertile Crescent. The vast lands in southwest Asia, northern Africa, and elsewhere, which in later times came to constitute the lands of Islam, the realms of the caliphs and, in modern parlance, the Arab world, still spoke other languages, professed other religions, and obeyed other rulers. Within little more than a century after the Prophet’s death, the whole area had been transformed, in what was surely one of the swiftest and most dramatic changes in the whole of human history. By the late seventh century, the outside world attests the emergence of a new religion and a new power, the Muslim empire of the caliphs, extending eastward in Asia as far as and sometimes beyond the borders of India and China, westwards along the southern Mediterranean coast to the Atlantic, southwards towards the land of the black peoples in Africa, northwards into the lands of the white peoples of Europe. In this empire, Islam was the state religion, and the Arabic language was rapidly displacing others to become the principal medium public life." Lewis, Bernard. THE MIDDLE EAST: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years, Touchstone Simon and Schuster, New York, 1995. pp 54-55

- ^ Morgan, Philip D. (2011). "Lowcountry Georgia and the Early Modern Atlantic World, 1733-ca. 1820". In Morgan, Philip D. (ed.). African American Life in the Georgia Lowcountry: The Atlantic World and the Gullah Geechee. Race in the Atlantic World, 1700-1900 Series. University of Georgia Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780820343075. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

[...] Georgia represented a break from the past. As one scholar has noted. it was 'a preview of the later doctrines of "systematic colonization" advocated by Edward Gibbon Wakefield and others for the settlement of Australia and New Zealand.' In contrast to such places as Jamaica and South Carolina, the trustees intended Georgia as 'a regular colony', orderly, methodical, disciplined [...]

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella. 2020. Global Language Politics: Eurasia versus the Rest (pp 118-151). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. Vol 14, No 2.

- ^ Terry Martin (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University press. p. 1. ISBN 0801486777.

- ^ Terry Martin (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University press. p. 32. ISBN 0801486777.

- ^ Per Anders Rudling (2014). The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931. University of Pittsburgh press. p. 212. ISBN 9780822979586.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W.W Norton Company, Inc. p. 558. ISBN 9780141912240.

- ^ Terry Martin (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University press. p. 409. ISBN 0801486777.

- ^ Richard Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W.W Norton Company, Inc. p. 556. ISBN 9780141912240.

- ^ George Hewitt (1999). The Abkhazians: A Handbook. Curzon Press. p. 96. ISBN 9781136802058.

- ^ Summary of Historical Events in Abkhazian History, 1810-1993 Abkhaz World, 15 October 2008, retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ The Stalin-Beria Terror in Abkhazia, 1936-1953, by Stephen D. Shenfield Abkhaz World, 30 June 2010, retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Malinkin, Mary Elizabeth (8 February 2016). "Building a Soviet City: the Transform of Königsberg". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

Joyous letters were written back home to the collective farms to encourage more people to come, but it was hard to convince people, so the local collective farm boards were given quotas of how many they needed to send to Kaliningrad and other places. They often sent people who were perceived as less useful for the farm – pregnant women, alcoholics, and the less educated, for example.

- ^ Vardys, Vytas Stanley (Summer 1964). "Soviet Colonialism in the Baltic States: A Note on the Nature of Modern Colonialism". Lituanus. 10 (2). ISSN 0024-5089.

- ^ David Chioni Moore (23 October 2020). "Is the Post- in Postcolonial the Post- in Post-Soviet? Toward a Global Postcolonial Critique". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Abene, Aija; Prikulis, Juris (2017). Damage caused by the Soviet Union in the Baltic States: International conference materials (PDF). Riga: E-forma. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-9934-8363-1-2.

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore A. (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 102–103. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- ^ Krūmiņš, Gatis. "The Investments of the USSR Occupying Power in the Baltic Economies – Myths and Reality" (PDF). Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences. pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Soviet occupation cost Latvian economy €185 billion, says research". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. LETA. 18 April 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Amin, Samir (Jul 2016). Russia and the Long Transition from Capitalism to Socialism. NYU Press. pp. 27–29. ISBN 9781583676035. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Nora Levin (1990). The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival, Volume 1. New York University Press. p. 283. ISBN 9780814750513.

- ^ Richard Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W.W Norton Company, Inc. p. 567. ISBN 9780141912240.

- ^ Arthur Rosen, [www./75mag/birobidzhan/birobidzhan.htm], February 2004

- ^ "Информационные материалы об окончательных итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года". Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ^ Constitution of the Russian Federation, Article 65

- ^ Спектор Р., руководитель Департамента Евро-Азиатского Еврейского конгресса (ЕАЕК) по связям с общественностью и СМИ (2008). под ред. Гуревич В.С.; Рабинович А.Я.; Тепляшин А.В.; Воложенинова Н.Ю. (eds.). "Биробиджан — terra incognita?" (PDF). Биробиджанский проект (опыт межнационального взаимодействия): сборник материалов научно-практической конференции. Биробиджан: ГОУ "Редакция газеты ". Правительство Еврейской автономной области: 20.

- ^ Zureik, Elia (2015). Israel's Colonial Project in Palestine: Brutal Pursuit. Routledge. p. [1]. ISBN 978-1-317-34046-1.

- ^ "Govt builds transmigration museum in Lampung | The Jakarta Post". June 4, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-06-04.

- ^ corporateName=Screen Australia; contact=webmaster; email=learning@screenaustralia. gov.au; address=PO Box 404, South Melbourne Vic 3205. "Screen Australia Digital Learning - Origins of the Bougainville Conflict (2000)". dl.nfsa.gov.au. Retrieved 2018-12-13.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "The CenSEI Report (Vol. 2, No. 13, April 2-8, 2012)". Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Government of Canada. ISBN 978-0-660-02078-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire: A Very Short Introduction. United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Mark Lacy (2014) Security, Technology and Global Politics, thinking with Virilio, page 20, Routledge ISBN 978-0-415-57604-8

- ^ Tim Luke & Gearoid O Tuathail (2000) "Thinking Geopolitical Space: The spatiality of war, speed and vision in the work of Paul Virilio", in Thinking Space, Mike Crang & Nigel Thrift editors, Routledge, quote page 368

- ^ Caroline Haskins (14 August 2018). "The racist language of space exploration". The Outline. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ DNLee (26 March 2015). "When discussing Humanity's next move to space, the language we use matters". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (2018-11-09). "We need to change the way we talk about space exploration". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

Bibliography[]

- Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13'000 years, 1997.

- Ankerl Guy, Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western, INUPress, Geneva, 2000. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Cotterell, Arthur. Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Swift Fall, 1415 - 1999 (2009) popular history; excerpt

- Colonialism