Decatur, Illinois

Decatur, Illinois | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Nickname(s): Soy City; Soybean Capital of the World; Limitless Decatur | |

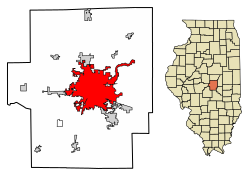

Location of Decatur in Macon County, Illinois | |

Decatur Location in Illinois | |

| Coordinates: 39°50′29.12″N 88°57′21.17″W / 39.8414222°N 88.9558806°WCoordinates: 39°50′29.12″N 88°57′21.17″W / 39.8414222°N 88.9558806°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Macon |

| Townships | Decatur, Harristown, Hickory Point, Long Creek, Oakley, South Wheatland, Whitmore |

| Founded | 1823 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor and City Manager | Julie Moore Wolfe and Scot Wrighton[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 47.00 sq mi (121.74 km2) |

| • Land | 42.32 sq mi (109.61 km2) |

| • Water | 4.68 sq mi (12.13 km2) 10.0%% |

| Elevation | 677 ft (206 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 70,522 |

| • Density | 1,671.69/sq mi (645.44/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT |

| ZIP code | 62521, 62522, 62523, 62526 |

| Area codes | 217, 447 |

| FIPS code | 17-18823 |

| Website | www |

Decatur /dɪˈkeɪtər/ is the largest city and the county seat of Macon County in the U.S. state of Illinois, with a population of 70,522 as of the 2020 Census. The city was founded in 1829 and is situated along the Sangamon River and Lake Decatur in Central Illinois. Decatur is the seventeenth-most populous city in Illinois.[4]

The city is home of private Millikin University and public Richland Community College. Decatur has an economy based on industrial and agricultural commodity processing and production, including the North American headquarters of agricultural conglomerate Archer Daniels Midland,[5] international agribusiness Tate & Lyle's largest corn-processing plant, and the designing and manufacturing facilities for Caterpillar Inc.'s wheel-tractor scrapers, compactors, large wheel loaders, mining class motor grader, off-highway trucks, and large mining trucks.

History[]

The city is named after War of 1812 naval hero Stephen Decatur.[6][7]

Decatur is an affiliate of the U.S. Main Street program, in conjunction with the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The Potawatomi Trail of Death passed through here in 1838.

Post No. 1 of the Grand Army of the Republic was founded by Civil War veterans in Decatur on April 6, 1866.

The Edward P. Irving House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright[8] and built in 1911, is located at No. 2 Millikin Place, Decatur. In addition, the Robert Mueller Residence, 1 Millikin Place,[9] and the Adolph Mueller Residence, 4 Millikin Place,[10][11] have been attributed to Wright's assistants Hermann V. von Holst and Marion Mahony.

Abraham Lincoln[]

Decatur was the first home in Illinois of Abraham Lincoln, who settled just west of Decatur with his family in 1830. At the age of 21, Lincoln gave his first political speech in Decatur about the importance of Sangamon River navigation that caught the attention of Illinois political leaders.[citation needed] As a lawyer on the 8th Judicial Circuit, Lincoln made frequent stops in Decatur, and argued five cases in the log courthouse that stood on the corner of Main & Main Streets. The original courthouse is now on the grounds of the Macon County Historical Museum on North Fork Road.[citation needed] John Hanks, first cousin of Abe Lincoln, lived in Decatur.

On May 9 and 10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. At this convention Lincoln received his first endorsement for President of the United States as "The Railsplitter Candidate." In commemoration of Lincoln's bicentennial, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur at the Decatur Conference Center and Hotel on June 6 & 7, 2008.[12]

ADM scandals and corporate exit[]

In early November 1992, the high-ranking Archer Daniels Midland Co. (ADM) executive Mark Whitacre confessed to an FBI agent that ADM executives, including Whitacre himself, had routinely met with competitors to fix the price of lysine, a food additive.

The lysine conspirators, including ADM, ultimately settled federal charges for more than $100 million. ADM also paid hundreds of millions of dollars ($400 million alone on the high-fructose corn syrup class action case) to plaintiffs and customers that it stole from during the price-fixing schemes.[13][14][15][16] Furthermore, several Asian and European lysine and citric acid producers that conspired to fix prices with ADM paid criminal fines in the tens of millions of dollars to the U.S. government.[17] Several executives, including the vice chairman of ADM, served federal prison time.

The investigation and prosecution of ADM and some of its executives has been reported to be one of the "best documented corporate crimes in American history".[18] The events were the basis of a book named The Informant, and a film by the same name.

In 2013, ADM reported that some employees had violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and ADM was fined 14 million U.S. dollars, but avoided criminal charges by self-reporting the foreign bribes.

In 2014, ADM moved its upper corporate management out of Decatur and established the new ADM World Headquarters in downtown Chicago. Following the ADM corporate exit, Decatur became listed by the United States Census Bureau as number 3 in "The 15 Fastest-Declining Large Cities" which showed a 7.1% population loss of (-5,376) from 2010 to 2019.[19]

Consecutive tornadoes[]

On April 18 and 19, 1996, the city was hit by tornadoes. On April 18, an F1 tornado hit the city's southeast side, followed by an F3 tornado the following evening on the northwest side. The two storms totaled approximately $10.5 million in property damage.[20]

Railcar explosion[]

On July 19, 1974, a tanker car containing isobutane collided with a boxcar in the Norfolk & Western railroad yard in the East End of Decatur. The resulting explosion killed seven people, injured 349, and caused $18 million in property damage.[21]

Jesse Jackson protest[]

In November 1999, Decatur was brought into the national news when Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition protested the expulsion and treatment of several African American students who had been involved in a serious fight at an Eisenhower High School football game.[22]

Geography[]

The USGS Domestic GeoNames resource has two listings for Decatur: "City of Decatur", which is a Civil-class designation, and "Decatur", which is a Populated Place designation, which have slightly different coordinate centroids: "City of Decatur" centroid is located at 39°51′20″N 88°56′01″W / 39.8556417°N 88.9337090°W,[23] while the "Decatur" centroid is at 39°50′25″N 88°57′17″W / 39.8403147°N 88.9548001°W.[24] Decatur is 150 miles southwest of Chicago, 40 miles east of Springfield, the state capital, and 110 miles northeast of St. Louis.

According to the 2010 census, consisted of 42.22 square miles (109.35 km2) land and 4.69 square miles (12.15 km2) of water,[25] together amounting to a total area of 46.91 square miles (121.50 km2), consisting of 90% land and 10% water. Lakes include Lake Decatur, an 11 km2 reservoir formed in 1923 by the damming of the Sangamon River, accounting for >90% of the state's census-designated water area.

The Decatur Metropolitan Statistical Area (population 109,900) includes surrounding towns of Argenta, Boody, Blue Mound, Elwin, Forsyth, Harristown, Long Creek, Macon, Maroa, Mount Zion, Niantic, Oakley, Oreana, and Warrensburg.

Climate[]

| hideClimate data for Decatur WTP, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

76 (24) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

105 (41) |

113 (45) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

96 (36) |

83 (28) |

72 (22) |

113 (45) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) |

39.1 (3.9) |

50.8 (10.4) |

63.4 (17.4) |

73.5 (23.1) |

82.2 (27.9) |

84.7 (29.3) |

83.5 (28.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

65.3 (18.5) |

50.3 (10.2) |

38.6 (3.7) |

61.9 (16.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.9 (−2.8) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

41.8 (5.4) |

53.3 (11.8) |

63.7 (17.6) |

72.6 (22.6) |

75.6 (24.2) |

74.2 (23.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

55.5 (13.1) |

42.3 (5.7) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

53.0 (11.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.7 (−6.8) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.3 (6.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

57.0 (13.9) |

45.7 (7.6) |

34.3 (1.3) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −23 (−31) |

−25 (−32) |

−10 (−23) |

15 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

45 (7) |

35 (2) |

20 (−7) |

12 (−11) |

−3 (−19) |

−22 (−30) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.40 (61) |

2.00 (51) |

2.64 (67) |

4.12 (105) |

4.95 (126) |

4.73 (120) |

4.00 (102) |

3.50 (89) |

3.08 (78) |

3.41 (87) |

3.21 (82) |

2.40 (61) |

40.44 (1,027) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.9 (15) |

2.5 (6.4) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

3.5 (8.9) |

13.6 (35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.2 | 8.3 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 13.3 | 10.5 | 9.5 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 115.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 9.6 |

| Source: NOAA[26][27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 3,839 | — | |

| 1870 | 7,161 | 86.5% | |

| 1880 | 9,547 | 33.3% | |

| 1890 | 16,841 | 76.4% | |

| 1900 | 20,754 | 23.2% | |

| 1910 | 31,140 | 50.0% | |

| 1920 | 43,818 | 40.7% | |

| 1930 | 57,510 | 31.2% | |

| 1940 | 59,305 | 3.1% | |

| 1950 | 66,269 | 11.7% | |

| 1960 | 78,004 | 17.7% | |

| 1970 | 79,285 | 1.6% | |

| 1980 | 94,081 | 18.7% | |

| 1990 | 83,885 | −10.8% | |

| 2000 | 81,860 | −2.4% | |

| 2010 | 76,122 | −7.0% | |

| 2020 | 70,522 | −7.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census [28][29] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 76,122 people, 32,344 households, and 18,991 families residing in the city.[30] The population density was 1,800.9 people per square mile (695.3/km2). There were 36,134 housing units at an average density of 854.8 per square mile (330.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 71.6% White, 23.3% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.9% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races.[30] Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.2% of the population.[30]

There were 32,344 households, out of which 24.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.4% were married couples living together, 16.9% had a female household with no husband present, and 41.3% were non-families. 35.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.86.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.1% under the age of 18, 10.8% from ages 18 to 24, 23.4% from ages 25 to 44, 26.8% from ages 45 to 64, and 16.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.0 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 85.3 males.

As of 2017, the median income for a household in the city was $41,977, and the median income for a family was $55,086. Males had a median income of $35,418 versus $34,389 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,042. About 22% of the population is below the poverty line, including 35% of those under age 18 and 10% of those age 65 or over.

Decatur is listed by the United States Census Bureau as number 3 in "The 15 Fastest-Declining Large Cities" which showed a 7.1% population loss of (−5,376) from 2010 to 2019.[19] The Chicago Tribune says: “in 1980, Decatur’s population was at a high of 94,000. Now it is 71,000."[31]

Civics[]

A new branding effort for Decatur and Macon County was unveiled in 2015, Limitless Decatur.[32] The intention of the marketing strategy was to attract and retain business and residents by promoting the Decatur area as modern and progressive with opportunities to live, work, and develop.[32]

For much of the 20th century, the city was known as "The Soybean Capital of the World" owing to its being the location of the headquarters of A. E. Staley Manufacturing Company, a major grain processor in the 1920s, which popularized the use of soybeans to produce products for human consumption such as oil, meal and flour.[33][34] At one time, over a third of all the soybeans grown in the world were processed in Decatur, Illinois. In 1955 a group of Decatur businessmen founded the Soy Capital Bank to trade on the nickname.

Decatur was awarded the All-America City Award in 1960, one of eleven cities honored that year.[35][36]

The city's symbol is the Transfer House,[37] an 1896 octagonal structure that was built in the original town square (now called "Lincoln Square") where the city's mass transit lines (streetcars and interurban trains) met. Designed by Chicago architect William W. Boyington, who also designed the famous Chicago Water Tower, the Transfer House was constructed to serve as a shelter for passengers transferring from one conveyance to another. It was regarded as one of the most beautiful structures of its kind in the United States, and a symbol of the city's high culture and modernity just decades after it was founded as a small collection of log cabins. The second story of the building consisted of an open-air gazebo used as a stage for public speeches and concerts by the Goodman Band. Sitting in the middle of the square as it was, increasing automobile traffic flowing through downtown Decatur on US 51 was forced to circle around the structure, and the Transfer House came to be seen by some as an impediment. The Illinois Department of Transportation, who maintained the US 51 highway route through Decatur, requested it be removed, and in 1962, the structure was transported by truck to nearby Central Park, where it stands today. In that location, it has served as a bus shelter, a visitor information center, and civic group offices.

Neighborhoods[]

On July 19, 1999, the Department of Community Development prepared a map of the official neighborhoods of Decatur, used for planning and statistical purposes. Decatur has 71 official neighborhoods.[38]

Sister cities[]

Decatur's sister cities are:[39]

Tokorozawa, Japan (since 1966)

Tokorozawa, Japan (since 1966) Seevetal, Germany (since 1975)

Seevetal, Germany (since 1975)

The Decatur Sister Cities Committee annually coordinates both inbound and outbound high school students, who serve as ambassadors among the three cities.[39]

Government[]

Between 1829 and 1836, the County Commissioners Court had jurisdiction as it was the seat of Macon County.[40][41] By 1836 the population reached approximately 300, and Richard Oglesby was elected president of the first board of trustees.[40] Other members of the board of trustees included Dr. William Crissey, H.M. Gorin and Andrew Love as clerk.[40][41]

In 1839 a town charter was granted to Decatur that gave power to the trustees "to establish and regulate a fire department, to dig wells and erect pumps in the streets, regulate police of the town, [and] raise money for the purpose of commencing and prosecuting works of public improvement."[40][41] Those who served as president of the town of Decatur were: Richard Oglesby (1836), Joseph Williams (1837), Henry Snyder (1838), Kirby Benedict (1839), Joseph King (1840), Thomas P. Rodgers (1841), David Crone (1846–47), J.H. Elliott (1848), Joseph Kauffman (1849), Joseph King (1850), William S. Crissey (1851), W.J. Stamper (1852), William Prather (1853–54), and Thomas H. Wingate (1854–55).[40]

In the winter of 1855–56, a special city incorporation charter was obtained.[40][41] This charter provided an aldermanic form of government and on January 7, 1856, an election was held for mayor, two aldermen for each of the four wards, and city marshal.[40][41] This aldermanic form of government continued until January 18, 1911, when Decatur changed to city commissioner form of government.[40][42] The new commissioner system provided a mayor elected at-large and four commissioners to serve as administrators of city services: accounts and finance, public health and safety, public property, and streets and public improvements. The mayor also served as Commissioner of Public Affairs.[42][43]

The mayor and commissioner system prevailed until a special election on November 25, 1958, in which the present council-manager form of government was adopted.[41][43] According to the city website, the "City of Decatur operates under the Council-Manager form of government, a system which combines the leadership of a representative, elected council with the professional background of an appointed manager."[44] The mayor and all members of the council are elected at-large. Their duties include determining city policy and representing the city in public ceremonies, for which they receive nominal annual salaries.[43] The appointed manager handles all city administration and is the council's employee, not an elected official.[43] Since 1959, the following have served as City Managers: John E. Dever, W. Robert Semple, Leslie T. Allen, Jim Bacon, Jim Williams, Steve Garman, John A. Smith (acting), Ryan McCrady, Gregg Zientara (interim), Timothy Gleason, and Scot Wrighton, the current holder.[45]

Julie Moore Wolfe serves as the current mayor of Decatur. Moore Wolfe was appointed unanimously by the Decatur City Council following the death of Mayor Mike McElroy.[46] She is the first female to be mayor of Decatur. Moore Wolfe, who had been appointed mayor pro tem in May 2015, became acting mayor after McElroy died on July 17, 2015.[47] McElroy had been mayor since 2009 and had recently been re-elected to a second term as mayor in April 2015.[48] Moore Wolfe was elected to a four-year term as mayor on April 4, 2017.[49]

Mayors[]

Those who served as president of the town of Decatur were: Richard Oglesby (1836), Joseph Williams (1837), Henry Snyder (1838), Kirby Benedict (1839), Joseph King (1840), Thomas P. Rodgers (1841), David Crone (1846–47), J.H. Elliott (1848), Joseph Kauffman (1849), Joseph King (1850), William S. Crissey (1851), W.J. Stamper (1852), William Prather (1853–54), and Thomas H. Wingate (1854–55).[40]

During the winter of 1855–56, a special incorporation charter of Decatur as a city was obtained providing for an aldermanic form of government.[40]

- John P. Post (1856)[40]

- William A. Barnes (1857)[40]

- James Shoaff (1858)[40]

- Alexander T. Hill (1859)[40]

- Sheridan Wait (1860)[40][50][51]

- Edward O. Smith (1861)[40]

- Thomas O. Smith (1862)[40]

- Jasper J. Peddecord (1863–1864)[40]

- Franklin Priest (1865–66; 1870, 1874, 1878)[40]

- John K. Warren (1867)[40]

- Isaac C. Pugh (1868)[40]

- William L. Hammer (1869)[40]

- E.M. Misner (1871)[40]

- D.S. Shellabarger (1872)[40]

- Martin Forstmeyer (1873)[40]

- R.H. Merriweather (1875)[40]

- William B. Chambers (1876–1877; 1883–1884; 1891–1892)[40]

- Lysander L. Haworth (1879)[40]

- Henry W. Waggoner (1880–1882)[40]

- Michael F. Kanan (1885–1890)[40]

- David C. Moffitt (1893–1894)[40]

- D.H. Conklin (1895–1896)[40]

- B.Z. Taylor (1897–1898)[40]

- George A. Stadler (1899–1900)[40]

- Charles F. Shilling (1901–1904)[40]

- George L. Lehman (1905–1906),[40]

- E.S. McDonald (1907–1908)[40]

- Charles M. Borchers (1909–1911; 1919–1923)[40]

- Dan Dinneen (1911–1919)[40]

- Elmer R. Elder (1923–1927)[40]

- Orpheus W. Smith (1927–1935)[40]

- Harry E. Barber (1935)[40]

- Charles E. Lee (1936–1943)[40]

- James A. Hedrick (1943–51)[40]

- Dr. Robert E. Willis (1951–1955)[40][52]

- Clarence A. Sablotny (1955–59)[40]

- Jack W. Loftus, acting (1959)[40]

- Robert A. Grohne (1959–1963)[40]

- Ellis B. Arnold (May 1, 1963, to April 30, 1967)[40]

- James H. Rupp (1966–1977)[40]

- Elmer W. Walton (1977–1983)[40]

- Gary K. Anderson (1983–1992)[40]

- Erik Brechnitz (1992–1995)[40]

- Terry M. Howley (1995–2003)[40]

- Paul Osborne (2003–2008) (resigned)

- Mike Carrigan (2008–2009) (appointed)

- Mike McElroy (2009–2015)

- Julie Moore Wolfe (2015–present) (appointed 2015, elected 2017)

Culture[]

Decatur Municipal Band[]

The Municipal Band was organized September 19, 1857, making it one of the oldest nonmilitary bands in continuous service in the United States and Canada.[53] The band was originally known as the Decatur Brass Band, Decatur Comet Band and Decatur Silver Band until 1871 when it was reorganized by Andrew Goodman and became The Goodman Band. In 1942, the band was officially designated as the Decatur Municipal Band and chartered within the City of Decatur. The present Decatur Municipal Band, directed by Jim Culbertson since 1979, is composed of high school and college students and area adults from all walks of life, all of whom look to the Band as a serious avocation, or as a prelude to a life-long profession.

Library[]

The Decatur Public Library was built with a grant from Andrew Carnegie. The library was built in 1902 at the corner of Eldorado and Main and opened to the public July 1, 1903. The building served the community until 1970 when the library moved to North Street at the site of a former Sears, Roebuck & Co. store. In 1999 the library moved to its present location on Franklin Street, which is also an abandoned Sears building. The library is part of the Illinois Heartland Library System. The original Carnegie library building was razed and in its place a bank was built.[54]

Sports[]

Professional football[]

Decatur was the original home of the Chicago Bears, from 1919 to 1920. The football team was then known as the Decatur Staleys and played at Staley Field, both named after the local food-products manufacturer.[55] A.E. Staley created the team from regular Staley Processing employees who had an interest in the sport. As the team continued to win games and show promise, Staley decided to invest in the team further by hiring George Halas as its first coach. Halas led the team to success in the 1919 season, going 10-1-2. As the team continued to win, Staley realized that he could make more money and further develop the team if there were larger crowds and a larger venue to play at. Halas and Staley agreed to move the team to Chicago in 1921 and play at Wrigley Field. The team was to play one season as the Chicago Staleys. In 1922, they played their first season as the Chicago Bears.[56]

Professional baseball[]

From 1900 to 1974, Decatur was the home of the Commodores, a minor-league baseball team playing at Fans Field.

Tennis[]

The USTA/Ursula Beck Pro Tennis Classic has been held annually since 1999. Male players from over 20 countries compete for $25,000 in prize money as well as ATP world ranking points at the Fairview Park Tennis Complex. The tournament is held for eight consecutive days at Fairview Park concluding on the first weekend in August.

Professional golf[]

Decatur formerly hosted the annual Decatur-Forsyth Classic presented by Tate & Lyle and the Decatur Park District. The tournament is traditionally held in June.[57][58] The final year for the tournament was 2019.

Softball[]

The following Decatur men's fast pitch softball teams have won national championships:

ADM[]

- 1981 Amateur Softball Association (ASA) Champions

- 1984 International Softball Congress (ISC) Champions

Decatur Pride[]

- 1994 Amateur Softball Association (ASA) Champions

- 1999 Amateur Softball Association (ASA) Champions

- 1999 Amateur Softball Association (ASA) Champions

- 2000 International Softball Congress (ISC) Champions

Media[]

Newspapers[]

- Decatur Tribune[59] —weekly

- The Decaturian[60] —bi-weekly student newspaper published by Millikin University

- Herald & Review —daily owned by Lee Enterprises

Magazines[]

- Decatur Magazine[61] —bi-monthly

Television[]

- 17 WAND, NBC

- 23 WBUI, CW

AM radio[]

- WDZ —1050AM—ESPN Radio

- WSOY—1340AM —Talk radio

- 1650 AM[62] —Community

FM radio[]

- WBGL —88.1 FM —Christian radio

- WDCR (FM) —88.9 FM & 96.5 FM —Relevant Radio

- WJMU —89.5 FM —Millikin University —Alternative rock

- WYDS —93.1 FM —Top 40

- WDZQ —95.1 FM —Country music

- WXFM[63] —99.3 —Light Hits

- WZUS —100.9 FM —Talk radio

- WLUJ — 101.9 FM – Moody Christian Radio

- WSOY —102.9 FM —Top 40

- WEJT —105.1 FM —Adult hits

- WCZQ —105.5 FM —Hip Hop & R&B

- WZNX —106.7 FM —Classic rock

- WDKR[63] —107.3 —Oldies

Economy[]

Industry[]

Decatur has production facilities for Caterpillar,[64] Archer Daniels Midland,[64] Mueller Co., and Tate & Lyle (previously A. E. Staley).[65]

The Japanese corporation Bridgestone owns Firestone Tire and Rubber Corporation, which operated a large tire factory here. Firestone's Decatur plant was closed in December 2001 in the midst of a tire failure controversy, and all 1,500 employees were laid off.[66] Firestone cited a decline in consumer demand for Firestone tires and the age of the Decatur plant as the reasons for closing that facility.[67]

Caterpillar Inc. has one of its largest manufacturing plants in the U.S. in Decatur. This plant produces Caterpillar's off highway trucks, wheel-tractor scrapers, compactors, large wheel loaders, mining-class motorgraders, and their ultra-class mining trucks (including the Caterpillar 797). Archer Daniels Midland processes corn and soybeans, Mueller produces water distribution products and Tate & Lyle processes corn in Decatur. From 1917 to 1922 Decatur was the location of the Comet Automobile Co.,[68] and the Pan-American Motor Corp.

Decatur has been ranked third in the nation as an Emerging Logistics and Distribution Center by Business Facilities: The Location Advisor,[69] and was named a Top 25 Trade City by Global Trade Magazine.[70] In 2013 the Economic Development Corporation of Decatur & Macon County established the Midwest Inland Port,[71] a multi-modal transportation hub with market proximity to 95 million customers in a 500-mile radius. The port includes the Archer Daniels Midland Intermodal container ramp, the two class I railroads that service the ramp and the city (the Canadian National Railway, and the Norfolk Southern Railway), five major roadways and the Decatur Airport. The Midwest Inland Port also has a foreign trade zone and customs clearing,[72] and the area is both an enterprise zone and tax increment financing district.

In August 2019, Mueller Company announced plans to construct a "state-of-the-art" brass foundry in Decatur on a 30 acre site in the 2700 block of North Jasper Street. The facility is expected to employee 250 personnel.[73]

In November 2020, ADM and InnovaFeed announced plans to construct the world's largest insect protein facility targeted to begin in 2021. The facility will be owned and operated by InnovaFeed and will co-locate with ADM's Decatur corn processing complex. This new project represents innovative, sustainable production to meet growing demand for insect protein in animal feed, a market that has potential to reach 1 million tons in 2027. Construction of the new high-capacity facility is expected to create more than 280 direct and 400 indirect jobs in the Decatur region by the second phase.[74]

Top employers[]

According to the EDC of Decatur & Macon County,[75] the top employers in Decatur are as follows:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Archer Daniels Midland | 4,000 |

| 2 | Caterpillar Inc. | 3,100 |

| 3 | Decatur Memorial Hospital[76] | 2,300 |

| 4 | Decatur Public Schools[77] | 1,800 |

| 5 | HSHS St. Mary's Hospital[78] | 1,000 |

| 6 | Millikin University | 600 |

| 7 | The Kelly Group[79] | 600 |

| 8 | Mueller Co. | 600 |

| 9 | Akorn Incorporated | 600 |

| 10 | Tate & Lyle | 600 |

Education[]

Colleges[]

- Millikin University (enrollment 2,400), a four-year institution of higher education, has a 75-acre (30 ha) campus founded by James Millikin and was originally affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

- Richland Community College (enrollment 3,500) is a comprehensive community college. It also hosts the biannual Farm Progress Show.

- Walther Theological Seminary is a Confessional Lutheran seminary affiliated with Pilgrim Lutheran Church.

Public schools[]

K–12 public education in the Decatur area is provided by the Decatur Public School District No. 61.[80] High school athletics were in the Big Twelve Conference up to 2013–14. The last two schools in Decatur joined the Central State Eight in the 2014–15 season.[81][82]

- Eisenhower High School (mascot: Panther)

- MacArthur High School (mascot: General)

Private schools[]

- Decatur Christian Schools[83] (mascot: Warrior)

- Holy Family Catholic School[84] (mascot: Knight)

- Lutheran School Association of Decatur[85] (mascot: Lion)

- Our Lady of Lourdes School[86] (mascot: Lancer)

- St. Patrick School[87] (mascot: Eagle)

- St. Teresa High School[88] (Mascot: Bulldog)

Infrastructure[]

Parks[]

Local Macon County park resources include Lake Decatur, Lincoln Trail Homestead State Memorial, Rock Springs Conservation Area, Fort Daniel Conservation Area, , Griswold Conservation Area, , and Spitler Woods State Natural Area. The Decatur Park District[89] resources include 2,000 acres (810 ha) of park land, an indoor sports center,[90] Decatur Airport, three golf courses, softball, soccer and tennis complexes, athletic fields, a community aquatic center, an AZA-accredited zoo, and a banquet, food and beverage business. Decatur was once dubbed "Park City USA" because it had more parks per person than any other city in the country,[citation needed] as well as "Playtown USA" because of Decatur's position as an early national leader in providing recreational space for its citizens. A motion picture short by that name was made in 1944 that featured the city's recreational efforts.[91]

Transportation[]

Air[]

Decatur Airport is served by daily commercial flights on Cessna 402 aircraft to and from Lambert-St. Louis International Airport and Chicago-O'Hare International Airport by Cape Air.

Rail[]

For more than 100 years, Decatur has been a major railroad junction and was once served by seven railroads. After mergers and consolidations, it is now served by two Class I railroads: the Norfolk Southern Railway, and the Canadian National Railway. The city is also served by Decatur Junction Railway, Decatur Central Railroad and shortlines.

Road[]

Interstate 72, U.S. Route 51, U.S. Route 36, Illinois Route 48, Illinois Route 105, and Illinois Route 121 are key highway links for the area.

Public transportation[]

The Decatur Public Transit System (DPTS) provides fixed-route bus service as well as complementary door-to-door paratransit service for people with disabilities, who are unable to use the bus system, throughout the City of Decatur. Under an agreement with the Village of Forsyth, service is also provided to the Hickory Point Mall area in Forsyth.

State government facilities[]

Decatur Correctional Center, a prison for women, is in the city.

Notable people[]

References[]

- ^ Herald & Review. "Meet Scot Wrighton, Decatur's New City Manager". Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ https://www.illinois-demographics.com/cities_by_population.

- ^ "North America". ADM Worldwide. ADM. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Callary, Edward (September 29, 2008). Place Names of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-252-09070-7.

- ^ Illinois Central Magazine. Illinois Central Railroad Company. 1922. p. 44.

- ^ "The Prairie School Traveler". The Prairie School Traveler. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Prairie School Traveler". The Prairie School Traveler. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Architecture – Adolph Mueller House". Pbs.org. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Prairie School Traveler". The Prairie School Traveler. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Ingram, Ron, "Ties to Lincoln draw state GOP convention to Decatur", Herald & Review, Decatur, Illinois, Thursday, July 14, 2007, http://www.herald-review.com/articles/2007/07/14/news/local_news/1024970.txt

- ^ Greenwald, John (October 28, 1996). The fix was in at ADM. Time Magazine.[1]

- ^ Wilson, J.K. (December 21, 2000). Price-Fixer to the World. Bankrate.com.[2]

- ^ KaplanFox (July 19, 2004). Archer Daniels Settles Suit Accusing it of Price Fixing. KaplanFox Law Firm Press Release.[3] Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Eichenwald, Kurt (2000). The Informant. Broadway Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7679-0327-1.[5]

- ^ Krebs, A.V. (August 16, 2000). Review of Rats in the Grain. The AgriBusiness Examiner (Issue #85). Archived from the original on November 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Decatur city, Illinois (Data in Table 2)". Southern and Western Regions Experienced Rapid Growth This Decade. May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "National Weather Service, Lincoln IL – Macon County Tornadoes Since 1950". Crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Decatur, IL Tank Cars Explode, July 1974". gendisasters.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "7 Students Charged in a Brawl That Divides Decatur, Ill". November 10, 1999. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "City of Decatur". U.S. Board on Geographic Names: Domestic Names. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "Decatur". U.S. Board on Geographic Names: Domestic Names. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Decatur, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Community Profiles". .illinoisbiz.biz. November 18, 2013. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Decatur city, Illinois". Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "Midwestern cities continue to lose population. Two of the fastest-shrinking are in Illinois". The Chicago Tribune. June 8, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lusvardi, Chris; Petty, Allison (May 8, 2015). "City Limitless extols Decatur area's potential". Herald & Review. Decatur, Illinois: Lee Enterprises. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Kane, Joseph Nathan; Alexander, Gerard L. (1965). Nicknames of Cities and States of the U.S.. The Scarecrow Press. p. 66. LCCN 65-13550 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Greetings from DECATUR Illinois, Soy Bean Capital of the World". idaillinois.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Past Winners of the All-America City Award". National Civic League. Winning Communities – 1960. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Past Winners". All-America City Winners (Search interface – filter on year 1960 and state Illinois to show Decatur; or search for Decatur, which returns Illinois as one of the search results.). National Civic League. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Decatur Transfer House". H. George Friedman, Jr. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ City of Decatur, IL. "Neighborhood Map". Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Decatur Sister Cities". Decatur Sister Cities Committee. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb Irwin, Dayle Cochran. Decatur: Serving Others, pg. 9[ISBN missing]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Banton, Oliver Terrill. History of Macon County (1976), pg. 275

- ^ Jump up to: a b Banton, Oliver Terrill. History of Macon County (1976), pg. 276

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Irwin, Dayle Cochran. Decatur: Serving Others, pg. 10

- ^ "Decatur Mayor and City Council". City of Decatur Illinois. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Petty, Allison (March 26, 2015). "Gleason promises he won't let city down". Herald&Review. Decatur, Illinois: Lee Enterprises. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Unanimous council appoints Moore Wolfe mayor".

- ^ "Decatur Mayor Mike McElroy passes away".

- ^ "Decatur mourning death of Mayor Mike McElroy on Friday".

- ^ "In historic moment, Moore Wolfe secures Decatur mayor win".

- ^ Staff (July 27, 1879). "Obituary, Major Sheridan Wait". Chicago Daily Tribune. XXXIX. p. 3 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers (Lib. of Congress).

In early life he was of the Democratic persuasion, and just before the War was elected major of Decatur on the Union ticket.

- ^ Staff (March 15, 1860). "Spring Elections (Decatur, Ill.)". The Press and Tribune. XIII (220). Chicago, Illinois. p. 1 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers (Lib. of Congress).

S. Wait, Democratic candidate for Mayor in Decatur, was elected by 132 majority, on Monday of last week;...

- ^ Martin, J. Neely (April 18, 1951). "24,000 Ballot; Davis, Holmes Join Council". The Decatur Review. 74 (92). p. 28 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ http://sites.google.com/view/decaturmuniband/history

- ^ "History". decaturlibrary.org. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ http://www.bearshistory.com/seasons/1920schicagobears.aspx

- ^ https://staleymuseum.com/history-of-the-staley-bearschicago-bears/

- ^ "Home | Symetra Professional Golfers | Tour Schedule, Leaderboard & News | Symetra Tour". Lpgafuturestour.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Decatur-Forsyth Classic". decaturforsythclassic.com. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Decatur Tribune

- ^ The Decaturian

- ^ Decatur Magazine

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WXFM 99.3/WDKR 107.3". decaturchamber.com. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b pdf.cat.com/cda/files/113505/.../2008%20WW%20location_final.pdf

- ^ http://www.tateandlyle.com/aboutus/history/pages/history.aspx

- ^ Kilborn, Peter T. (December 14, 2001). "An Illinois Tire Plant Closes and a Way of Life Fades". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ Barboza, David (June 28, 2001). "Bridgestone/Firestone to Close Tire Plant at Center of Huge Recall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ http://www.dalnet.lib.mi.us/henryford/docs/CometAutomobileCompanyRecords_Accession1771.pdf

- ^ "FEATURE STORY: Game-Changer In The Heartland". Business Facilities (BF) Magazine. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Midwest Inland Port

- ^ "Decatur Airport". decatur-parks.org. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Perry, Scott (October 28, 2019). "Mueller Water Products breaks ground for state-of-the-art foundry in Decatur". Decatur Herald & Review. Lee Enterprises. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ https://www.decaturedc.com/innovafeed/

- ^ "Industries Here". decaturedc.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Decatur Memorial Hospital, Decatur, Illinois – DMH Cares About Your Health". dmhcares.org. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Decatur Public Schools / Overview". dps61.org. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "St. Mary's Hospital, Decatur, Illinois – Exceptional Health Care". stmarysdecatur.com. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Kelly Group, Decatur, Illinois". thekelly-group.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ Decatur Public School District #61

- ^ "Conferences Affiliated Schools". ihsa.org. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Richey, Scott (March 13, 2013). "Central State 8 eagerly adds Decatur schools".

- ^ Decatur Christian Schools

- ^ Holy Family Catholic School

- ^ Lutheran School Association of Decatur

- ^ Our Lady of Lourdes School

- ^ "St. Patrick's School". Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ St. Teresa High School

- ^ "Decatur Park District – Decatur Park District". decatur-parks.org. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Decatur Indoor Sports Center (DISC) – Decatur Park District". decatur-parks.org. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Playtown USA". Retrieved November 28, 2017.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Decatur, Illinois. |

- Official website

Decatur (Illinois) travel guide from Wikivoyage

Decatur (Illinois) travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Decatur, Illinois

- Cities in Illinois

- County seats in Illinois

- Populated places established in 1836

- Cities in Macon County, Illinois

- Metropolitan areas of Illinois

- 1836 establishments in Illinois