East River Tunnels

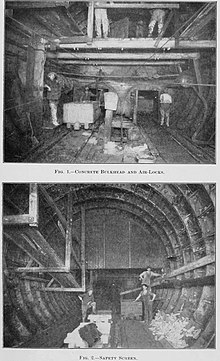

Construction of the East River Tunnels, 1909 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | Northeast Corridor |

| Location | East River between Manhattan and Queens in New York City |

| Operation | |

| Constructed | 1904–1909 |

| Opened | September 8, 1910 |

| Owner | Amtrak |

| Traffic | Rail |

| Character | Passenger |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | Alfred Noble |

| Length | 3,949 feet (1,204 m)[1] |

| Width | 23 feet (7.0 m)[1] |

East River Tunnels | |

The East River Tunnels are four single-track railroad passenger service tunnels that extend from the eastern end of Pennsylvania Station under 32nd and 33rd Streets in Manhattan and cross the East River to Long Island City in Queens. The tracks carry Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and Amtrak trains travelling to and from Penn Station and points to the north and east. The tracks also carry New Jersey Transit trains deadheading to Sunnyside Yard. They are part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, used by trains traveling between New York City and New England via the Hell Gate Bridge.

History[]

Construction[]

The tunnels were built in the first decade of the 20th century as part of the New York Tunnel Extension. The original plan for the extension which was published in June 1901, called for the construction of a bridge across Hudson River between 45th and 50th Streets in Manhattan, as well as two closely spaced terminals for the LIRR and Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). This would allow passengers to travel between Long Island and New Jersey without having to switch trains; at the time, LIRR trains ran to Long Island City, where passengers took ferries across the East River to the 34th Street Ferry Terminal in Manhattan. As part of the extension, the LIRR became a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad.[2] In December 1901, because of the high cost of building a bridge,[3] the plans were modified so that the PRR would construct the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River.[4]

The New York Tunnel Extension quickly gained opposition from the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners, who objected that they would not have jurisdiction over the new tunnels, as well as from the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, which saw the New York Tunnel Extension as a potential competitor to its as-yet-incomplete rapid transit service.[5] The project was approved by the New York City Board of Aldermen in December 1902, on a 41-36 vote. The North and East River Tunnels were to built under the riverbed of their respective rivers. The PRR and LIRR lines would converge at New York Penn Station, an expansive Beaux-Arts edifice between 31st and 33rd Streets in Manhattan. The entire project was expected to cost over $100 million.[6]

The contract for building the East River Tunnels was awarded to S. Pearson & Son in 1903.[7] Originally, the tunnel would have comprised two tubes, but this was later expanded to four tubes.[8] The project was led by Chief Engineer Alfred Noble.[9]

Work began in 1904.[10]: 111 The four tunnels were built simultaneously, digging east from Penn Station, west from Long Island City, and east and west from shafts just east of First Avenue. The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown.[11] The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use. Construction was completed on the East River tunnels on March 18, 1908.[12]

Opening[]

The tubes opened along with Pennsylvania Station on September 8, 1910.[13][1][14]

Long Island City Area Track Map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As part of the New York Connecting Railroad improvement project, a connection from the East River Tunnels to the New Haven Railroad tracks was also built. New Haven trains began running through the East River Tunnels, serving Penn Station, in 1917 after the Hell Gate Bridge opened.[15]: 30 [17]

Later years[]

The East River Tunnels were flooded with 14 million US gallons (53,000,000 L) of water during Hurricane Sandy in 2012.[18][19] Even after the tunnels were drained, corrosion continued to occur inside the tunnels, and the signal systems broke down increasingly frequently compared to before the storm. Amtrak, which owns the tunnels, originally proposed to start repairing the tunnels in 2019 at a cost of $1 billion, with each tunnel being closed for two years. However, due to delays in the East Side Access project that would give LIRR riders a second direct route into Manhattan via the 63rd Street Tunnel, Amtrak later pushed back the start date of the East River Tunnels' reconstruction to 2025, and increased the construction time to four years.[20]

Operation[]

The East River Tunnels are owned by Amtrak and are electrified by both third rail and overhead catenary. Diesel-powered locomotives are not allowed in the tunnels except in emergency because of ventilation concerns, so the LIRR uses DM30AC dual-mode locomotives to power a few trains from non-electrified lines into and out of Penn Station during rush hours.

East of Penn Station, tracks 5–21 merge into two 3-track tunnels, which then merge into the East River Tunnels' four tracks. The tunnels end and the tracks rise to ground level east of the Queens shoreline.[17] The four lines under the river are numbered south to north, Lines 1 and 2 running beneath 32nd Street and Lines 3 and 4 under 33rd Street. Eastward trains usually use Lines 1 and 3, and westbound usually use Lines 2 and 4. To bring the same-direction tunnels into adjacency, line 3 crosses beneath line 2 underground a few hundred feet west of the east end of the Line 2 tunnel.[15]: 36

- East portals for Lines 1 and 3: 40°44′34″N 73°56′42″W / 40.7429°N 73.9450°W

- East portal for Line 2: 40°44′32″N 73°56′54″W / 40.7421°N 73.9483°W

- East portal for Line 4: 40°44′35″N 73°56′45″W / 40.74305°N 73.94585°W

Approaching Harold Interlocking from the west, the four tracks are Lines 1-3-2-4 south to north (with three LIRR tracks between Lines 2 and 3, and Sunnyside Yard approach tracks scattered between the passenger tracks). East of Harold, Lines 1-3 become LIRR Main Line Tracks 4-2 south to north, while Lines 2-4 become LIRR Main Line Track 3 and the westward Port Washington main. (Harold was rearranged in 1990; until then Lines 2-4 became the westward Port Washington and the westward Hell Gate track).

See also[]

- North River Tunnels (Hudson River tunnels to New Jersey)

- New York Tunnel Extension (construction project for East River Tunnels)

References[]

- ^ a b c Guide to Civil Engineering Projects In and Around New York City (2nd ed.). Metropolitan Section, American Society of Civil Engineers. 2009. p. 58.

- ^ "NORTH RIVER BRIDGE PLAN; Pennsylvania Road Negotiating with Banking Houses". The New York Times. June 26, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL A SUBMERGED BRIDGE; New York Terminal to be a Magnificent Structure. DETAILED PLANS DISCLOSED Vice President Rea Credited with the Idea Which Will, Experts Believe, Advance the City's Interests to an Unparalleled Degree". The New York Times. December 13, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL UNDER NORTH RIVER; Property Already Acquired for the Great New York Terminal. TO PUSH THE CONSTRUCTION City Neighborhoods' to be Improved -- Depth of the Tunnel So Great Subways Will Not Be Obstructed". The New York Times. December 12, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "MORE OPPOSITION TO PENNSYLVANIA'S BILL; Rapid Transit Commissioners Will Appear Against It. THEIR RIGHTS INFRINGED E.M. Shepard and A.B. Boardman, Counsel for Board, Say that It Af- fects That Body's Usefulness -- Mr. Cassatt's Views". The New York Times. March 21, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED; Aldermen Approve the Grant by a Vote of 41 to 36 Borough President Cantor Speaks and Votes Against the Measure -- Excited Debate Before the Final Action. PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED". The New York Times. December 17, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "O'ROURKE WILL BUILD PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL; New York Firm Gets Contract for North River Section. BRITISH TO BORE OTHER TUBE S. Pearson & Son, Limited, of London, the Successful Bidders for Work Under the East River". The New York Times. March 12, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Herries, W. (1906). Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac ...: A Book of Information, General of the World, and Special of New York City and Long Island ... Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 456. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Brace, James (1912). "The East River Division". In Couper, William (ed.). History of the Engineering Construction and Equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York Terminal and Approaches. New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co. p. 79.

- ^ Gilbert, Gilbert H.; Wightman, Lucius I.; Saunders, William L. (1912). "The East River Tunnels of the Pennsylvania Railroad". The Subways and Tunnels of New York: Methods and Costs, with an Appendix on Tunneling Machinery and Methods and Tables of Engineering Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Industrial Magazine. Geo. S. Mackintosh. 1907. p. 79. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "FOURTH RIVER TUBE THROUGH; Last of Pennsylvania-Long Island Tunnels Connected -- Sandhogs Celebrate". The New York Times. March 19, 1908. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "DAY LONG THRONG INSPECTS NEW TUBE; 35,000 Persons Were Carried on the First Day of Pennsylvania's Tunnel Service. ACCIDENT MARRED OPENING Morning Trains Delayed Two Hours by Broken Third Rail -- Some Complaints Over Extra Fare". The New York Times. September 9, 1910. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Schafer, Mike; Brian Solomon (2009) [1997]. Pennsylvania Railroad. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-7603-2930-6. OCLC 234257275.

- ^ a b c Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- ^ Lynch, Andrew (2020). "New York City Subway Track Map" (PDF). vanshnookenraggen.com. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Mills, William Wirt (1908). Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels and terminals in New York City. Moses King. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak Hopes To Have East River Tunnels Damaged By Sandy Restored By Christmas". CBS New York. November 27, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ "LIRR still years away from some Sandy repairs". Newsday. October 30, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak: Sandy tunnel repair may begin in 2025". Newsday. October 19, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- Tunnels in Manhattan

- Transportation buildings and structures in Queens, New York

- Crossings of the East River

- Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels

- Railroad tunnels in New York City

- Tunnels completed in 1910

- Amtrak tunnels

- Long Island City

- 1910 establishments in New York City

- NJ Transit Rail Operations

- New York Tunnel Extension

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas