North River Tunnels

Western portal at Bergen Hill | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Line | Northeast Corridor | ||

| Location | Hudson Palisades-Hudson River | ||

| Coordinates | 40°46′17″N 74°02′31″W / 40.7714°N 74.0419°WCoordinates: 40°46′17″N 74°02′31″W�� / 40.7714°N 74.0419°W | ||

| System | Amtrak and NJ Transit | ||

| Start | Bergen Hill in Weehawken, New Jersey | ||

| End | Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, New York City | ||

| |||

The North River Tunnels are a pair of tunnels that carry Amtrak and New Jersey Transit rail lines under the Hudson River between Weehawken, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, New York City, New York. Built between 1904 and 1908 by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) to allow its trains to reach Manhattan, they opened for passenger service in late 1910.

The tunnels allow a maximum of 24 crossings per hour each way and operate near capacity during peak hours. The tunnels were damaged by flooding in 2012, causing frequent delays in train operations. In May 2014, Amtrak stated that within 20 years one or both of the tunnels would have to be shut down. In May 2021, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) approved two new tunnels, although specific funding sources for the complete project were not identified.

History[]

Context[]

The PRR had consolidated its control of railroads in New Jersey with the lease of United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company in 1871, extending its network from Philadelphia northward to Jersey City. Crossing the Hudson River remained an obstacle; to the east, the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) ended at the East River. In both situations, passengers had to transfer to ferries to Manhattan. This put the PRR at a disadvantage relative to its arch competitor, the New York Central Railroad, which already served Manhattan.[5]

After unsuccessfully trying to create a bridge over the Hudson River, the PRR and the LIRR developed several proposals for improved regional rail access in 1892 as part of the New York Tunnel Extension project. The proposals included new tunnels between Jersey City and Manhattan, and possibly one to Brooklyn; a new terminal in midtown Manhattan for both the PRR and LIRR, completion of the Hudson Tubes (later called PATH), and a bridge proposal. These proposals finally came to fruition at the turn of the century, when the PRR created subsidiaries to manage the project. The Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York Railroad, incorporated on February 13, 1902, was to oversee construction of the North River Tunnels. The PNJ&NY would also be in charge of the Meadows Division, which would handle the construction of the North River Tunnel approaches on the New Jersey side.[6]

The original proposal for the PRR and LIRR terminal in Midtown, published in June 1901, called for the construction of a bridge across Hudson River between 45th and 50th Streets in Manhattan, and two closely spaced terminals for the LIRR and PRR. This would allow passengers to travel between Long Island and New Jersey without changing trains.[7] In December 1901, the plans were modified so that the PRR would construct the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River, instead of a bridge over it.[8] The PRR cited costs and land value as a reason for constructing a tunnel rather than a bridge, since the cost of a tunnel would be one-third that of a bridge. The North River Tunnels themselves would consist of between two and four steel tubes with the diameter of 18.5 to 19.5 feet (5.6 to 5.9 m).[9] The New York Tunnel Extension quickly gained opposition from the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners, who objected that they would not have jurisdiction over the new tunnels, as well as from the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, which saw the New York Tunnel Extension as a potential competitor to its as-yet-incomplete rapid transit service.[10] The project was approved by the New York City Board of Aldermen in December 1902, on a 41–36 vote. The North and East River Tunnels were to be built under the riverbed of their respective rivers. The PRR and LIRR lines would converge at New York Penn Station, an expansive Beaux-Arts edifice between 31st and 33rd Streets in Manhattan. The entire project was expected to cost over $100 million.[11][12]

Design and construction[]

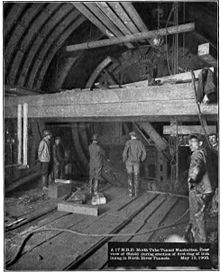

Led by Chief Engineer Charles M. Jacobs, the tunnel design team began work in 1902.[13] The contract for building the North River Tunnels was awarded to O'Rourke Engineering Construction Company in 1904.[14] Originally, the tunnel would have comprised three tubes, but this was later downsized to two tubes.[15] The first construction work comprised the digging of two shafts: one just east of 11th Avenue a few hundred yards east of the river's eastern shore; and a larger one in Weehawken, a few hundred yards west of the river's western shore. Construction on the Weehawken Shaft started in June 1903. It was completed in September 1904 as a concrete-walled rectangular pit, 56 by 116 ft (17.1 by 35.4 m) at the bottom and 76 ft (23.2 m) deep.[12]

When the shafts were complete, O'Rourke began work on the tunnels proper. The project was divided into three parts, each managed by a resident engineer: the "Terminal Station" in Manhattan; the "River Tunnels", east from the Weehawken Shaft and under the Hudson River; and the Bergen Hill tunnels, west from the Weehawken Shaft to the tunnel portals on the west side of the Palisades.[16]: 45 The tunnels were built with drilling and blasting techniques and tunnelling shields, which were placed at three locations and driven towards each other. The shields proceeded west from Manhattan, east and west from Weehawken, and east from the Bergen portals.[17]

Under the river itself, the tunnels started in rock, using drill and blast, but the strata under the river was pure mud for a considerable depth. As a result, this part was driven under compressed air, using 194-ton shields that met about 3,000 feet (910 m) from the Weehawken and Manhattan portals. The mud was such that the shield was shoved forward without taking any ground; however, it was found that the shield was easier to steer if some mud was taken in through holes at the front, since the mud had the consistency of toothpaste. After the tubes had been excavated, they were lined with 2.5-foot-wide (0.76 m) segmental cast-iron rings, each weighing 22 tons. The segments were bolted together and lined with 22-inch (56 cm) of concrete.[18]: 200 The two ends of the northern tube under the river met in September 1906; at that time it was the longest underwater tunnel in the world.[3][19]

Meanwhile, the John Shields Construction Company had begun in 1905 to bore through Bergen Hill, the lower Hudson Palisades;[20] William Bradley took over in 1906 and the tunnels to the Hackensack Meadows were completed in April 1908.[21][22]

Opening and use[]

The tunnels opened November 27, 1910, when the New York Tunnel Extension to New York Penn Station opened.[23]: 37 Until then, PRR trains used the PRR main line to Exchange Place in Jersey City, New Jersey. The New York Tunnel Extension branched off from the original line two miles northeast of Newark, then ran northeast across the Jersey Meadows to the North River Tunnels and New York Penn.[24] The tunnel project included the Portal Bridge over the Hackensack River and the Manhattan Transfer interchange with the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (now PATH).[23]: 37, 39 The opening of the North River Tunnels and Penn Station made the PRR the only railroad with direct access to New York City from the south.[25]

In 1967 the Aldene Plan was implemented, allowing trains of the floundering Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) and Reading (RDG) to run to Newark Penn Station, connecting to PRR and PATH trains to New York.[23]: 61 [26] The PRR merged into Penn Central Transportation in 1968.[27] Penn Central went bankrupt in 1970[23]: 61 [26] and in 1976 its suburban trains were taken over by Conrail,[28][29] then by NJ Transit in 1983.[30] Penn Central long-distance service (including part of today's Northeast Corridor and Empire Corridor) had been taken over by Amtrak in 1971.[31] Amtrak took control of the North River Tunnels in 1976, and NJ Transit started running trains through the tunnels under contract with Amtrak.[32]

Operation[]

Portals[]

The west portals are in North Bergen, at the west edge of the New Jersey Palisades near the east end of Route 3 at U.S. Route 1/9 (40°46′17″N 74°02′31″W / 40.7714°N 74.0419°W). They run beneath North Bergen, Union City, and Weehawken, to the east portals at the east edge of 10th Avenue at 32nd Street in Manhattan. When the top of the Weehawken Shaft was covered is a mystery; the two tracks may have remained open to the sky until catenary was added circa 1932. The two portals on the Manhattan side fanned out into 21 tracks just east of 10th Avenue, serving the platforms at Penn Station.[18]: 200 450 West 33rd Street (now Five Manhattan West), on the east side of 10th Avenue, was built above the east portals in 1969.[33][34]

Except for a curve west of the west end of Pier 72 that totals just under a degree, the two tracks are straight (in plan view). They are 37 feet (11.3 m) apart from west of 11th Avenue to the Bergen Hill portals. The third rail now ends just west of the Bergen Hill portals.

Capacity and useful life[]

The North River Tunnels allow a maximum of 24 crossings per hour each way.[35][36] Since 2003, the tunnels have operated near capacity during peak hours.[2] The number of NJ Transit weekday trains through the North River Tunnels increased from 147 in 1976 to 438 in 2010.[37] Trains ordinarily travel west (to New Jersey) through the north tube and east through the south. During the busiest hour of morning rush, about 24 trains are scheduled through the south tube, and the same number travel through the north tube in the afternoon.

The tubes run parallel to each other underneath the river; their centers are separated by 37 feet (11 m). The two tracks fan out to 21 tracks just west of Penn Station.[12][38]: 399 [39]: 76

Expansion and restoration proposals[]

Beginning in the 1990s several proposals were developed to build additional tunnels under the Hudson, both to add capacity for Northeast Corridor traffic and to allow repairs to be made to the existing deteriorated tunnels. A plan to repair the tunnels and add new tubes was approved in 2021.[40]

Access to the Region's Core[]

Access to the Region's Core (ARC), launched in 1995 by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), NJ Transit, and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, was a Major Investment Study that looked at public transportation ideas for the New York metropolitan area. It found that long-term goals would best be met by better connections to and in-between the region's major rail stations in Midtown Manhattan, Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal.[41] The East Side Access project, including tunnels under the East River and the East Side of Manhattan, which would divert some LIRR traffic to Grand Central, is expected to be completed in December 2022.[42]

The Trans-Hudson Express Tunnel or THE Tunnel, which later took on the name of the study itself, was meant to address the western, or Hudson River, crossing. Engineering studies determined that structural interferences made a new terminal connected to Grand Central or the current Penn Station unfeasible and its final design involved boring under the current rail yard to a new deep cavern terminal station under 34th Street.[43][44] Amtrak had acknowledged that the region represented a bottleneck in the national system and had originally planned to complete work by 2040.[45]

The ARC project, which did not include direct Amtrak participation,[45][46] was cancelled in October 2010 by New Jersey governor Chris Christie, who cited potential cost overruns.[47] Amtrak briefly engaged the governor in attempt to revive the ARC Tunnel and use preliminary work done for it, but those negotiations soon broke down.[48][45][46] Amtrak said it was not interested in purchasing any of the work.[49] New Jersey Senator Robert Menendez later said some preparatory work done for ARC may be used for the new project.[50] Costs for the project were $117 million for preliminary engineering, $126 million for final design, $15 million for construction and $178 million real estate property rights ($28 million in New Jersey and $150 million in New York City). Additionally, a $161 million partially refundable pre-payment of insurance premiums was also made.[51] Subsequently, Amtrak's timetable for beginning its trans-Hudson project was advanced. This was in part due to the cancellation of ARC, a project similar in scope, but with differences in design.[52]

Gateway Program and Hurricane Sandy[]

Amtrak's plan for a new Trans-Hudson tunnel, the Gateway Program was unveiled on February 7, 2011, by Amtrak CEO Joseph Boardman and New Jersey Senators Menendez and Frank Lautenberg.[53][54][37][55] The announcement also included endorsements from New York Senator Charles Schumer and Amtrak's Board of Directors. Officials said Amtrak would take the lead in seeking financing; a list of potential sources included the states of New York and New Jersey, the City of New York, the PANYNJ, and the MTA as well as private investors.[56][48][57] As of 2017, the Gateway Program is expected to cost $12.9 billion.[58][59]

In October 2012, a year after the Gateway Program was announced, the North River Tubes were inundated by seawater from Hurricane Sandy, marking the first time in the tunnel's history that both tubes had been completely flooded.[60][50][61] The surge damaged overhead wires, electrical systems, concrete bench walls, and drainage systems.[50] As a result of the storm damage and the tunnels' age, component failures within the tubes increased, resulting in frequent delays.[62] One report in 2019 estimated that the North River Tubes and the Portal Bridge, two components the Gateway Program seeks to replace, contributed to 2,000 hours of delays between 2014 and 2018.[63] After the North River Tunnels were flooded, the Gateway Program was prioritized. In May 2014, Boardman told the Regional Plan Association that there was less than 20 years before one or both of the tunnels would have to be shut down.[64] In July 2017, the draft Environmental Impact Study for the project was issued.[59]

Funding for the Gateway Project had been unclear for several years due to a lack of funding commitments from New Jersey officials and the federal government. In 2015, a Gateway Development Corporation, consisting of members from Amtrak, the Port Authority and USDOT, was created to oversee construction of the Gateway Project. The federal government and the states agreed to split the cost of funding the project.[65][66] The administration of President Donald Trump has cast doubts about funding for the project,[67][68] and in December 2017, a Federal Transit Administration official called the previous funding agreement "nonexistent".[69][70] In March 2018, up to $541 million for the project was provided in the Consolidated Appropriations Act.[71][72] On June 24, 2019, the state governments of New York and New Jersey passed legislation to create the bi-state Gateway Development Commission, whose job it is to oversee the planning, funding and construction of the rail tunnels and bridges of Gateway Program.[73] In February 2020, Amtrak indicated that it would go forward with the renovation of the North River Tunnels regardless of the Gateway Program's status.[74][75]

On May 28, 2021, the project was formally approved by USDOT, with funding still to be determined. Amtrak's cost estimate for the project, as of 2021, is $11.6 billion, which would include repairs to the existing tunnels. One or more federal funding bills pending in 2021 may be used to support the project. The states of New Jersey and New York are maintaining their pledge to provide a portion of the project funding.[40][76][77]

Service and repair plans[]

If and when the new Gateway Program tunnels are built, the two North River Tunnels would close for repairs, one at a time, with the existing level of service maintained. The North River Tubes and the Gateway Program tunnels would both be able to carry a maximum of 24 trains per hour.[78] Once the new North River tunnels reopen in 2030, capacity on the line would be doubled. The Hudson Tunnel Project would also allow for resiliency on the Northeast Corridor to be increased, making service along the line more reliable with redundant capacity.[79]: S-2 to S-3, S-10 [80]: 5B-17

The existing North River Tunnels can carry a maximum of 24 trains per hour in each direction.[35][36] If the new Hudson Tunnel is not built, the North River Tunnels will have to be closed one at a time, reducing weekday service below the existing level of 24 trains per hour. Due to the need to provide two-way service on a single track, service would be reduced by over 50 percent.[36] In the best-case scenario, with perfect operating conditions, 9 trains per hour could be provided through the existing North River Tunnels, or a 63% reduction in service. During the duration of construction, passengers would have to use overcrowded PATH trains, buses, and ferries to get between New Jersey and New York.[81]: 1–7 On the other hand, if the new Gateway tunnel is built, it would allow an additional 24 trains per hour to travel under the Hudson River, supplementing the 24 trains per hour that could use the existing North River tubes.[78]

See also[]

- Bergen Hill

- Bergen Tunnels

- East River Tunnels

- List of bridges, tunnels, and cuts in Hudson County, New Jersey

- List of ferries across the Hudson River in New York City

- List of fixed crossings of the Hudson River (bridges and tunnels)

- Uptown Hudson Tubes (PATH transit tunnels, opened 1908)

References[]

- ^ Guide to Civil Engineering Projects In and Around New York City (2nd ed.). Metropolitan Section, American Society of Civil Engineers. 2009. p. 58.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Belson, Ken (April 6, 2008). "Tunnel Milestone, and More to Come". The New York Times. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "'Pennsy's' North River Tunnel a Marvel of Skill; Bores Meeting Head-on Under the River Only an Eighth of an Inch Out of Alignment and Three-fourths of an Inch Out of Grade" (PDF). The New York Times. September 9, 1906.

- ^ "Fishermap". fishermap.org. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Schafer, Mike; Brian Solomon (2009) [1997]. Pennsylvania Railroad. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-7603-2930-6. OCLC 234257275.

- ^ Couper, William. (1912). History of the Engineering Construction and Equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York Terminal and Approaches. New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co. pp. 7–16.

- ^ "NORTH RIVER BRIDGE PLAN; Pennsylvania Road Negotiating with Banking Houses". The New York Times. June 26, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL UNDER NORTH RIVER; Property Already Acquired for the Great New York Terminal. TO PUSH THE CONSTRUCTION City Neighborhoods' to be Improved -- Depth of the Tunnel So Great Subways Will Not Be Obstructed". The New York Times. December 12, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL A SUBMERGED BRIDGE; New York Terminal to be a Magnificent Structure. DETAILED PLANS DISCLOSED Vice President Rea Credited with the Idea Which Will, Experts Believe, Advance the City's Interests to an Unparalleled Degree". The New York Times. December 13, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "MORE OPPOSITION TO PENNSYLVANIA'S BILL; Rapid Transit Commissioners Will Appear Against It. THEIR RIGHTS INFRINGED E.M. Shepard and A.B. Boardman, Counsel for Board, Say that It Af- fects That Body's Usefulness -- Mr. Cassatt's Views". The New York Times. March 21, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED; Aldermen Approve the Grant by a Vote of 41 to 36 Borough President Cantor Speaks and Votes Against the Measure -- Excited Debate Before the Final Action. PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED". The New York Times. December 17, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mills, William Wirt (1908). Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels and terminals in New York City. Moses King. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "TUNNEL ENGINEERS NAMED.; Commission of Experts Appointed for Pennsylvania Railroad's Proposed Route Under New York Harbor". The New York Times. 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "O'ROURKE WILL BUILD PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL; New York Firm Gets Contract for North River Section. BRITISH TO BORE OTHER TUBE S. Pearson & Son, Limited, of London, the Successful Bidders for Work Under the East River". The New York Times. March 12, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Herries, W. (1906). Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac ...: A Book of Information, General of the World, and Special of New York City and Long Island ... Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 456. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Charles M. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad, The North River Division". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. American Society of Civil Engineers. LXVIII. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Hewett, B.H.M. (1912). "The North River Division". History of the Engineering Construction and Equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York Terminal and Approaches. New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co. pp. 35–53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scientific American. Library of American civilization. Munn & Company. 1910. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "Meeting of the Pennsylvania Tunnel Shields". The Railway Age. Chicago: Wilson Co. 42 (12): 355. September 21, 1906.

- ^ "Penn. Tunnel Award" (PDF). The New York Times. March 14, 1905. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Final Blast Opens Pennsylvania Tube" (PDF). The New York Times. April 9, 1908. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Another Tube Through" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1908. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- ^ "Pennsylvania Opens Its Great Station; First Regular Train Sent Through the Hudson River Tunnel at Midnight". The New York Times. November 27, 1910.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Railroad Company - American railway". Encyclopedia Britannica. March 1, 1976.

- ^ Jump up to: a b French, Kenneth (2002). Images of America:Railroads of Hoboken and Jersey City. USA: Arcadia Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7385-0966-2. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015.

- ^ Hammer, Alexander R. (January 31, 1968). "Court Here Lets Railroads Consolidate Tomorrow" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ^ "A Brief History of Conrail". Consolidated Rail Corporation. 2003. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Conrail, The Consolidated Rail Corporation". American-Rails.com. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Goldman, Ari L. (January 3, 1983). "State Agencies Take Command of Conrail Lines". The New York Times.

- ^ Pinkston, Elizabeth (2003). "A Brief History of Amtrak." The Past and Future of U.S. Passenger Rail Service. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congressional Budget Office)

- ^ Sullivan, John (June 2, 2002). "New Jersey's Amtrak Blues". The New York Times.

- ^ Cunningham, Cathy; Grossman, Matt; Cunningham, Cathy (April 13, 2018). "Brookfield Lands $1.2B Landesbank Loan for 5 Manhattan West". Commercial Observer. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "Ad giant IPG grows to 280K sf at Brookfield's 5 Manhattan West". The Real Deal New York. January 26, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NJ Transit's Response to Shifting Travel Demand in the Aftermath of September 11, 2001" (PDF). Travel Trends. New Brunswick: The Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center. 3. Fall 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2017, State of New Jersey" (PDF). Amtrak. 2017. p. 3. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Gateway Project" (PDF). Amtrak. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Completion of the Pennsylvania Tunnels and Terminal Station". Scientific American. Library of American civilization. Munn & Company (v. 102). May 14, 1910. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGeehan, Patrick (May 28, 2021). "At Long Last, a New Rail Tunnel Under the Hudson River Can Be Built". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Access to the Region's Core Major Investment Study Summary Report 2003" (PDF). arctunnel.com. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Long Island Committee Meeting December 2015" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 14, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ New Jersey Transit (October 2008). Newark, NJ. "Access to the Region's Core: Final Environmental Impact Study." Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Executive Summary.

- ^ Rassmussen, Ian (December 15, 2010). "When an Environmental Impact Statement takes a lifetime". New Urban News. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

The story of ARC began in 1995 with the start of a "Major Investment Study" that reviewed 137 alternative transportation improvements that would get commuters from central and northern New Jersey out of their cars, and into Manhattan faster, cheaper, and with less harm to the environment. After four years of study, the list was narrowed down to a few finalists in 1999. From 1999 to 2003, the feasibility of each of those plans (exactly where the tracks would be laid, and how they would connect to Penn Station) was studied, and the ultimate plan ironed out. From 2003 to 2009, the final plan — two new rail tunnels leading to a new lower level of Penn Station — was the subject of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Frassinelli, Mike (November 8, 2010). "Hudson River tunnel project proposed by Amtrak, NJ Transit would take decades to complete". The Star Ledger. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Amtrak, NJ Transit break off talks on reviving ARC Hudson River rail tunnel", The Star-Ledger, November 12, 2010, retrieved March 7, 2011

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (October 7, 2010). "Christie Halts Train Tunnel, Citing Its Cost". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Frassinelli, Mike (February 8, 2011). "Gov. Christie says new Gateway tunnel plan addresses his ARC project cost concerns". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ "Amtrak: no interest in Hudson tunnel", The Star-Ledger, November 13, 2010, retrieved March 13, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Higgs, Larry (September 1, 2014). "Amtrak: New tunnels needed after Sandy damage". Asbury Park Press.

- ^ Pillets, Jeff (February 28, 2011). "State wants refund for $161.9M tunnel insurance". The Record. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ Fleisher, Liza; Grossman, Andrew (February 8, 2011), "Amtrak's Plan For New Tunnel Gains Support", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved February 8, 2011

- ^ Rouse, Karen (February 8, 2011). "Amtrak president details Gateway Project at Rutgers lecture". Bergen Record. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Frassinelli, Mike (February 6, 2011). "N.J. senators, Amtrak official to announce new commuter train tunnel project across the Hudson". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (February 7, 2011). "With One Plan for a Hudson Tunnel Dead, Senators Offer Another Option". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ "Lautenberg, Menendez Join Amtrak to Announce New Trans-Hudson Gateway Tunnel Project" (Press release). Lautenberg/US Senate press release. February 7, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ Caruso, Lisa (February 7, 2011). "Amtrak Proposes $13.5 Billion New Jersey Rail Project". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Price for New York-New Jersey rail tunnel rises to $12.9B". ABC News. July 6, 2017. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bazeley, Alex (July 6, 2017). "The Hudson Tunnel Project is expected to cost $12.9 billion". am New York. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak Tunnels Flooded During Sandy To Reopen Friday". CBS New York. November 7, 2012.

- ^ Frassinelli, Mike (November 8, 2012). "Transportation update: Amtrak to reopen flooded Hudson River rail tunnel". The Star Ledger.

- ^ "Sandy-damaged tunnels could cause Amtrak nightmare". AP News. October 2, 2014.

- ^ "How bad are delays caused by North River Tunnel and Portal Bridge? 2,000 lost hours bad". Mass Transit Magazine. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ Rubinstein, Dana (May 5, 2014). "Clock ticking on Hudson crossings, Amtrak warns". Capital. Archived from the original on May 10, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Maag, Christopher (November 12, 2015). "Officials: Corporation will oversee new Hudson rail tunnel; feds will split cost". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved March 22, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Feds agree to fund half of new Hudson rail tunnels, Booker says". NJ.com. November 12, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Reitmeyer, John (March 20, 2017). "Trump Infrastructure Flip-Flop Could Put Gateway Tunnel Project in Peril". NJ Spotlight. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ "Build a tunnel, a great tunnel, and make the feds pay for it - Editorial". NJ.com. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Betz, Bradford (December 31, 2017). "Trump pulls brakes on $13B Obama-backed rail-tunnel plan". Fox News.

- ^ Bredderman, Will (December 29, 2017). "Trump administration kills Gateway tunnel deal". Crain's New York.

- ^ DeBonis, Mike; O'Keefe, Ed; Werner, Erica (March 22, 2018). "Here's what Congress is stuffing into its $1.3 trillion spending bill". The Washington Post.

- ^ Guse, Clayton (March 27, 2018). "A pair of crucial new Hudson River tunnels just took a major step forward". Time Out New York.

- ^ Wanek-Libman, Mischa (June 24, 2019). "Bi-state legislation passed to establish Gateway Development Commission". Mass Transit Magazine.

- ^ Mann, Ted (February 28, 2020). "Amtrak to Begin Repairs to Tunnels Beneath Hudson River". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (February 27, 2020). "More Pain for N.J. Commuters: Tunnel Repairs Could Cause Big Delays". The New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (May 28, 2021). "Gateway project to build new Hudson River tunnels wins key federal approval". nj. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Porter, David (May 28, 2021). "$11 Billion New York-New Jersey Rail Tunnel Gets Key Federal Approval". NBC New York. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Porcari, John D. (January 12, 2017). "Gateway Program Overview and Update" (PDF). Gateway Program Development Corporation. p. 21.

- ^ "Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) Executive Summary" (PDF). Hudson Tunnel Project. Federal Railroad Administration; New Jersey Transit. June 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ "Hudson Tunnel Project Draft Environmental Impact Study; Chapter 5B: Transportation Services" (PDF). Hudson Tunnel Project. Federal Railroad Administration; New Jersey Transit. June 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ "Hudson Tunnel Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Chapter 1: Purpose and Need" (PDF). Hudson Tunnel Project. June 2017.

External links[]

Media related to North River Tunnels at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to North River Tunnels at Wikimedia Commons- Reeve, Arthur B. (December 1906). "The Romance of Tunnel Building: The Sixteen Subaqueous Tunnels Built and Building Under the Rivers Around New York City". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIII: 8338–8351. Retrieved July 10, 2009. Includes numerous construction photos.

- Animated graphic of North River Tunnel construction technique - The New York Times

- "Tunnel to Terminus: The Story of Penn Station" - National Public Radio

- Amtrak tunnels

- Tunnels in Hudson County, New Jersey

- Tunnels in Manhattan

- Railroad tunnels in New Jersey

- Railroad tunnels in New York City

- Crossings of the Hudson River

- Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels

- Tunnels completed in 1910

- NJ Transit Rail Operations

- Historic American Engineering Record in New Jersey

- New York Tunnel Extension