Environmental issues in China

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (July 2021) |

Environmental issues in China had risen in tandem with the country's rapid industrialisation, as well as lax environmental oversight especially during the early 2000s. China was ranked 120th out of the 180 countries on the 2020 Environmental Performance Index.[1]

The Chinese government has acknowledged the problems and made various responses, resulting in some improvements, but western media has criticized the actions as inadequate.[2] In recent years, there has been increased citizens' activism against government decisions that are perceived as environmentally damaging,[3][4] and a retired government official claimed that the year of 2012 saw over 50,000 environmental protests in China.[5]

Since the 2010s, the government has given greater attention to environmental protection through policy actions such as the signing of the Paris climate accord, the 13th Five-Year Plan and the 2015 Environmental Protection Law reform [6] From 2006 to 2017, sulphur dioxide levels in China were reduced by 70 percent,[7] and air pollution has decreased from 2013 to 2018[8] In 2017, investments in renewable energy amounted to US$279.8 billion worldwide, with China accounting for US$126.6 billion or 45% of the global investments.[9] China has since become the world's largest investor, producer and consumer of renewable energy worldwide, manufacturing state-of-the-art solar panels, wind turbines and hydroelectric energy facilities as well as becoming the world’s largest producer of electric cars and buses.[10]

Environmental problems[]

Water resources[]

The water resources of China are affected by both severe water quantity shortages and severe water quality pollution. An increasing population and rapid economic growth as well as lax environmental oversight have increased water demand and pollution. China has responded by measures such as rapidly building out the water infrastructure and increased regulation as well as exploring a number of further technological solutions. Water usage by its coal-fired power stations is drying-up Northern China.[11][12][13]

According to Chinese government in 2014 59.6% of groundwater sites are poor or extremely poor quality.[14]

A 2016 research study indicated that China's water contains dangerous amounts of the cancer-causing agent nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA). In China, NDMA is thought to be a byproduct of local water treatment processes (which involve heavy chlorination).[15]

Deforestation[]

Although China's forest cover is only about 20% [16][17] the country has some of the largest expanses of forested land in the world, making it a top target for forest preservation efforts. In 2001, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) listed China among the top 15 countries with the most "closed forest," i.e., virgin, old growth forest or naturally regrown woods.[18] 12% of China's land area, or more than 111 million hectares, is closed forest. However, the UNEP also estimates that 36% of China's closed forests are facing pressure from high population densities, making preservation efforts especially important. In 2011, Conservation International listed the forests of south-west Sichuan as one of the world's ten most threatened forest regions.[19]

China had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.14/10, ranking it 53rd globally out of 172 countries.[20]

Three Gorges dam[]

The three gorges dam produces 3% of the electricity in China but has displaced houses and caused environmental problems within the local environment. Due to the construction of the dam over one million people have been displaced from their homes.[21] The dam has also caused frequent major landslides due to the erosion in the reservoir. These major landslides included two incidents in May 2009 when somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 cubic metres (26,000 and 65,000 cu yd) of material plunged into the flooded Wuxia Gorge of the Wu River.[22]

Coastal reclamation[]

China's marine environment, including the Yellow Sea and South China Sea, are considered among the most degraded marine areas on earth.[23] Loss of natural coastal habitats due to land reclamation has resulted in the destruction of more than 65% of tidal wetlands around China's Yellow Sea coastline in approximately 50 years.[24] Rapid coastal development for agriculture, aquaculture and industrial development are considered the primary drivers of coastal destruction in the region.[24][25]

Desertification[]

Desertification remains a serious problem, consuming an area greater than the area used as farmland. Although desertification has been curbed in some areas, it is still expanding at a rate of more than 67 km2 every year. 90% of China's desertification occurs in the west of the country.[26] Approximately 30% of China's surface area is desert. China's rapid industrialization could cause this area to drastically increase. The Gobi Desert in the north currently expands by about 950 square miles (2,500 km2) per year. The vast plains in northern China used to be regularly flooded by the Yellow River. However, overgrazing and the expansion of agricultural land could cause this area to increase.[27] In 2009, it was estimated that over 200 high-altitude lakes in Zoigê Marsh, which provides 30% of the Yellow River's water, had dried up.[28]

Climate change[]

Climate Change had already impacted China. It increased mortality from extreme weather events, infectious disease, poor air and water quality. The effects of air pollutions are exacerbated by the rise in temperatures. In the future climate change may lead to "typhoons, floods, blizzards, windstorms, drought, and landslides" and to more severe damage from infectious diseases[29]

According to one report, China is the country with the largest number of people who can be impacted by Sea level rise.[30]

One of the main problems is the melting of glaciers and permafrost in Tibet. These glaciers and permafrost supply water to approximately 2 billion people. The temperatures in the region rise 4 times faster than anywhere in Asia. According to Xinhua News Agency 18% of glaciers already melted from the middle of the 20th century. The water level in big rivers is lowering. This has an impact on the water supply of China because many rivers, including the Yangtze and Yellow River are getting water from the Tibet glaciers. According to China's Ministry of Water Resources 28,000 of rivers disappeared in China by the year 2013 and the melting of Tibet glaciers and permafrost can be one of the causes. The melting also has an impact on the water supply of others countries in eastern Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and more, that can lead to conflicts over water. According to Chinese Academy of Science "more than 80 percent of Tibetan Plateau permafrost could be gone by the year 2100, and that almost 40 percent of it would be gone within the “near future.” Some researchers even suppose that most of the Himalayan glaciers will disappear in 20 years.[31]

Pollution[]

Various forms of pollution have increased as China has further industrialized, which has caused widespread environmental and health problems.[32] China has responded with increasing environmental regulations and a build-up of pollutant treatment infrastructure which have caused improvements on some variables. As of 2013 Beijing, which lies in a topographic bowl, has significant industry, and heats with coal, is subject to air inversions resulting in extremely high levels of pollution in winter months.[33] In response to an increasingly problematic air pollution problem, the Chinese government announced a five-year, US$277 billion plan to address the issue. Northern China will receive particular attention, as the government aims to reduce air emissions by 25 percent by 2017, compared with 2012 levels, in those areas where pollution is especially serious.[34] According to a report published by Greenpeace and Peking University's School of Public Health in December 2012, the coal industry is responsible for the highest levels of air pollution (19 percent), followed by vehicle emissions (6 percent). Ambient air pollution is measured by the amount of particulate matter in the air. This is a result of burning fossil fuels. “Because coal is the primary fuel used to power China’s industrial sector, it is responsible for about 40 percent of the deadly fine particulate matter found in China’s atmosphere.” [35] In January 2013, fine airborne particulates that pose the largest health risks, rose as high as 993 micrograms per cubic meter in Beijing, compared with World Health Organization guidelines of no more than 25. The World Bank estimates that 16 of the world's most-polluted cities are located in China.[36]

Coastal pollution is widespread, leading to declines in habitat quality and increasing harmful algal blooms.[37] The largest algal bloom recorded in history occurred in China around the southern Yellow Sea in 2008, and was easily observed from space.[38]

Rising affluence is another indirect cause of pollution. In particular, car ownership has skyrocketed. In 2014, China added a record 17 million new cars to the road and car ownership reached 154 million.[39]

China is the biggest producer of single use plastic what causes severe pollution. The biggest landfill of the country was filled 25 years before it was planned.[40]

Land pollution[]

In July 2015, Council on Foreign Relations Director of Asia Studies Elizabeth Economy writing in The Diplomat listed soil contamination as a "poor stepchild" of the Chinese environmental movement, and questioned whether or not recent measures from the Ministry of Environmental Protection would be adequate in combating the problem.[41] In her 2004 book The River Runs Black, she wrote, "China's spectacular economic growth over the past two decades has dramatically depleted the country's natural resources and produced skyrocketing rates of pollution. Environmental degradation has also contributed to significant public health problems, mass migration, economic loss, and social unrest."[42]

Population[]

China currently has the world's largest population but population growth is very slow in part due to the one-child policy. The environmental issues are also negatively affecting the people living in China. Because of the emissions created from the factories, the number of people diagnosed with cancer in China has increased. Lung cancer is the most common form of cancer that is plaguing the population. In 2015, there were more than 4.3 million new cancer cases in the country and more than 2.8 million people died from the disease.[43]

Animal welfare[]

According to a 2005-2006 survey by Peter J. Li, many farming methods that the European Union is trying to reduce or eliminate were commonplace in China, including gestation crates, battery cages, foie gras, early weaning of cows, and clipping of ears/beaks/tails. In a 2012 interview, Li mentioned that many livestock in China may be transported over long distances and there are currently no humane-slaughter requirements. He also mentioned that China is the biggest fur-producing nation, and — while the government had been trying to standardize slaughtering procedures — there were cases where fur animals have been skinned alive or beaten to deaths with sticks.[44]

About 10,000 Asiatic black bears are farmed for bile production—an industry worth roughly $1.6 billion per year.[44] The bears are permanently kept in cages, and bile is extracted from cuts in their stomachs.[44] Jackie Chan and Yao Ming have publicly opposed bear farming.[45][46][47] In 2012, over 70 Chinese celebrities took part in a petition against an IPO application by Fujian Guizhentang Pharmaceutical Co. due to the company's selling of bear-bile medicines.[48]

Natural disasters[]

According to Jared Diamond, the six main categories of environmental problems of China are: air pollution, water problems, soil problems, habitat destruction, biodiversity loss and mega projects.[27] He also explained that "China is noted for the frequency, number, extent, and damage of its natural disasters".[27] Some natural disasters in China are "closely related to human environmental impacts", especially: dust storms, landslides, droughts and floods.[27]

Response[]

General overview of the environmental policy[]

In 2012 the Center for American Progress has described China's environmental policy as similar to that of the United States before 1970. That is, the central government issues fairly strict regulations, but the actual monitoring and enforcement is largely undertaken by local governments that are more interested in economic growth. Furthermore, due to the restrictive conduct of China's undemocratic regime, the environmental work of non-governmental forces, such as lawyers, journalists, and non-governmental organizations, is severely hampered.[49]

Since 2002, the number of complaints to the environmental authorities increased by 30 percent every year, reaching 600,000 in 2004; meanwhile, according to an article by the director of the Ma Jun in 2007, the number of mass protests caused by environmental issues grew by 29 percent every year since that time.[50][51] The growing attention upon environmental matters caused the Chinese government to display an increased level of concern towards environmental issues and the creation of sustainable growth. For example, in his annual address in 2007, Wen Jiabao, the Premier of the People's Republic of China, made 48 references to "environment," "pollution," and "environmental protection", and stricter environmental regulations were subsequently implemented. Some of the subsidies for polluting industries were cancelled, while some polluting industries were shut down. However, although the promotion of clean energy technology occurred, many environmental targets were missed.[52]

After the 2007 address, polluting industries continued to receive inexpensive access to land, water, electricity, oil, and bank loans, while market-oriented measures, such as surcharges on fuel and coal, were not considered by the government despite their proven success in other countries. The significant influence of corruption was also a hindrance to effective enforcement, as local authorities ignored orders and hampered the effectiveness of central decisions. In response to a challenging environmental situation, President Hu Jintao implemented the "Green G.D.P." project, whereby China's gross domestic product was adjusted to compensate for negative environmental effects; however, the program lost official influence in spring 2007 due to the confronting nature of the data. The project's lead researcher claimed that provincial leaders terminated the program, stating "Officials do not like to be lined up and told how they are not meeting the leadership’s goals ... They found it difficult to accept this."[52]

China included the target of achieving Ecological civilization in its constitution, but there are some concerns about implementation.[53]

In March 2014, CPC General Secretary Xi Jinping "declared war" on pollution during the opening of the National People's Congress.[54] After extensive debate lasting nearly two years, the parliament approved a new environmental law in April. The new law empowers environmental enforcement agencies with great punitive power, defines areas which require extra protection, and gives independent environmental groups more ability to operate in the country.[55] The new articles of the law specifically address air pollution, and call for additional government oversight.[54] Lawmaker Xin Chunying called the law "a heavy blow [in the fight against] our country's harsh environmental realities, and an important systemic construct".[55] Three previous versions of the bill were voted down. The bill is the first revision to the environmental protection law since 1989.[55]

In 2019, it launched the Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition.

In 2020, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping announced that China aims to peak emissions before 2030 and go carbon-neutral by 2060 in accordance with the Paris climate accord.[56]According to Climate Action Tracker, if accomplished it would lower the expected rise in global temperature by 0.2 - 0.3 degrees - "the biggest single reduction ever estimated by the Climate Action Tracker".[57]

In 2020, a sweeping law was passed by the Chinese government to protect the ecology of the Yangtze River. The new laws include strengthening ecological protection rules for hydropower projects along the river, banning chemical plants within 1 kilometer of the river, relocating polluting industries, severely restricting sand mining as well as a complete fishing ban on all the natural waterways of the river, including all its major tributaries and lakes.[58]

Reforestation[]

According to the Chinese government website, the Central Government invested more than 40 billion yuan between 1998 and 2001 on protection of vegetation, farm subsidies and conversion of farmland to forest.[59] Between 1999 and 2002, China converted 7.7 million hectares of farmland into forest.[60]

33.8 million hectares (338,000 km2) of forest had been planted in China in the years 2013 - 2018. The Chinese government pledged to increase the forest cover of the country from 21.7% to 23% in the years 2016 - 2020[61] and to 26% by the year 2035[62] According to the government's plan, by 2050, 30% of China's territory should be covered by forests.[63] According to the govrment's Xinhua News Agency one third of the population of China participated in tree planting in the first half on 2020. 1.69 billion trees were planted, increasing the forest cover by 4.43 million hectares.[64]

In December 2020 China proposed a new Nationally Determined Contribution (but still not submitted it). According to it China will increase its forest stock volume by 6 billion cubic metres by 2030 (instead of 4.5 billion cubic metres before)[65]

Ou Hongyi the single climate striker of China created an initiative named "Plant for survival". In 2 – 3 months, more than 300 trees were planted.[66]

Stopping erosion and desertification[]

In 1994, China started the Loess Plateau Watershed Rehabilitation Project.

In 2001, China initiated a "Green Wall of China" project. It is a project to create a 2,800-mile (4,500 km) "green belt" to hold back the encroaching desert. The first phase of the project, to restore 9 million acres (36,000 km2) of forest, will be completed by 2010 at an estimated cost of $8 billion. The Chinese government believes that, by 2050, it can restore most desert land back to forest. The project is possibly the largest ecological project in history.[67] It has also been criticized on various grounds such as other methods being more effective.[68]

Official targets on climate change mitigation[]

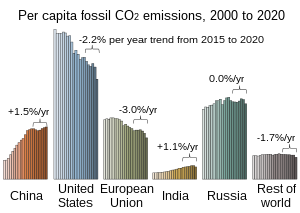

2 emissions in China and the rest of world have eclipsed the output of the United States and Europe.[69]

The position of the Chinese government on climate change is contentious. China is the world's current largest emitter of carbon dioxide although not the cumulative largest. China has ratified the Kyoto Protocol, but as a non-Annex I country was not required to limit greenhouse gas emissions under terms of the agreement.

In September 2020, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping announced that China will "strengthen its 2030 climate target (NDC), peak emissions before 2030 and aim to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060".[70] According to Climate Action Tracker if it will be accomplished it will lower the expected rise in global temperature by 0.2 - 0.3 degrees - "the biggest single reduction ever estimated by the Climate Action Tracker".[71] The announcement was made in the United Nations General Assembly. Xi Jinping mentioned the link between the corona pandemic and nature destruction as one of the reasons for the decision, saying that "Humankind can no longer afford to ignore the repeated warnings of nature."[72]

On the 27 September 2020, China's climate scientists presented a detailed plan how to achieve the target, described as "The most ambitious climate goal the world’s ever seen". According to the plan GHG emission will begin to decline between 2025 and 2030, while total energy consumption will do so in 2035. By 2050 China will stop producing electricity with coal. By 2025, 20% of energy will be produced without fossil fuels. According to the plan GHG emissions will reach 10.2 billion tons between 2025 and 2030, decline to 9 billion by 2035, 3 billion by 2050 and 200 million by 2060. The emissions that will rest by 2060 will be mitigated with Carbon capture and storage, Carbon sequestration, Bioenergy.[73][74]

In the 2021 Leaders' Climate Summit China pledged to strictly limit the growth in coal consumption by 2025 and reduce the use of coal from 2026.[75]

Energy efficiency[]

According to a 2007 article, during the 1980 to 2000 period the energy efficiency improved greatly. However, in 1997, due to fears of a recession, tax incentives and state financing were introduced for rapid industrialization. This may have contributed to the rapid development of very energy inefficient heavy industry. Chinese steel factories used one-fifth more energy per ton than the international average. Cement needed 45 percent more power, and ethylene needed 70 percent more than the average. Chinese buildings rarely had thermal insulation and used twice as much energy to heat and cool as those in the Europe and the United States in similar climates. 95% of new buildings did not meet China's own energy efficiency regulations.[52]

A 2011 report by a project facilitated by World Resources Institute stated that the 11th five-year plan (2005 to 2010), in response to worsening energy intensity in the 2002-2005 period, set a goal of a 20% improvement of energy intensity. The report stated that this goal likely was achieved or nearly achieved. The next five-year plan set a goal of improving energy intensity by 16%.[76]

Adaptation to climate change[]

Sponge cities in China are a way of adaptation to flooding exacerbated by climate change and urbanization. China has been noted for its effort in adopting the Sponge City initiative. In 2015, China was reported to have initiated a pilot initiative in 16 districts.[77][78][79][80]

Animal Welfare[]

There are currently no nationwide animal welfare laws in China.[44][81][82] However, the World Animal Protection notes that some legislation protecting the welfare of animals exists in certain contexts, especially ones used in research and in zoos.[83]

In 2006, Zhou Ping of the National People's Congress introduced the first nationwide animal-protection law in China, but it didn't move forward.[84] In September 2009, the first comprehensive Animal protection law of the People's Republic of China was introduced, but it hasn't made any progress.[82]

In 2016, the Chinese government adopted a plan to reduce China's meat consumption by 50%, for achieving more sustainable and healthy food system.[85][86]

Reducing plastic pollution[]

In 2017 China banned the import of most types of plastic. In 2019 it announced a ban on single use plastic, but it should enter into force gradually, through 6 years. China's government is trying to replace it with biodegradable plastic, but it can work only in certain conditions. Refillable containers can solve the problem better.[40]

In September 2020, the Ministry of Commerce announced a ban on single-use plastic bags and single-use cutlery in big cities by the end of the year, as well as a nationwide ban on single-use plastic straws.[87]

Community activism[]

As a result of more incidents relating to natural disasters and negative health consequences tied to environmental issues,[88] sociologists Deng Yanhua and Yang Guobin write that more people in China are “becoming increasingly environmentally concerned and may organize protests against anticipated pollution.”[89] According to Ronggui Huang and Xiaoyi Sun, “many environmental protests are tolerated by the Chinese authority, because protests are seen by the central government as an information-gathering channel to identify the dangerously discontented social groups and to monitor local officials.”[90] This increase in environmental action in the late 20th century has accomplished the growth of awareness which led to the rise of environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs).[91] ENGOs have engaged in campaigns that have seen some success.[92] The world and scholars all over have been interested in ENGOs given their existence in an authoritarian state and position that some expect will “counterbalance environment-unfriendly economic forces”.[93] Some of these scholars argue that ENGOs have become more legitimate given new environmental laws that aim to curb negative environmental practices in China.[94]

Alongside the rise of ENGOs, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (formerly known as the State Environmental Protection Administration or SEPA) began to rise in power since its creation in the 1970s.[95] Bureaucratic constraints forced the Ministry to partner with organizations outside of the government to be more successful.[96] The ENGOs with their vast networks and methods appeared to be a good choice in partner for the ministry.[97]

Opposition to the Nujiang dam project was one campaign in which shows the partnership between the ENGOs and SEPA.[98] The project introduced in 2003 indented to build reservoirs and dams along the Nujiang River.[99] The movement against the project, which halted construction in 2016[100] was “a peak in the history of China’s environmental movement.”[101] According to sociologists Yanfei Sun and Dingxin Zhao reasons for this was the higher risk involved following the environmental action and government response to the Three Gorges Dam.[102] According to the South China Morning Post cooperation from different activist groups developed during the opposition to the project. Previously these groups “tended to work alone due to the strong personalities of their leaders.”[103] Wang Yongchen, founder of the ENGO Green Earth Volunteers has been a strong voice in this campaign against the dam project.[104]

Organizers employ a variety of methods that have developed in response to potential issues that environmental action faces. Some of these issues include environmental science not being widely accessible and understood by the general population,[105] bureaucratic constraints in legal channels, [106] fear of government suppression,[107] the difficulty in proving the health-related consequences of pollution,[108] economic blackmail,[109] and the antagonistic relationships between local governments and ENGOs.[110]

Success in environmental action would also appear to depend on the organizers themselves and how effective they can be overall.[111] Several scholars argue that framing environmental issues properly has been a successful method “used by environmental activists to mobilize citizens behind the protests”.[112] Deng Yanhua and Yang Guobin write that piggybacking onto other political issues is another successful method.[113] For example, instead of following through with environmental claims, there has been success in piggybacking onto the issue of land claims in order “to maximize the vulnerability of their opponents.”[114] In order to work, the issue in question must be framed not as an environmental issue, but a land-related one. This happened during the 2005 Huashui protest targeting factory pollution that took place in Zhejiang Province where organizers framed the issue as illegal land acquisition.

The protests that began on June 28, 2019[115] in Wuhan against a proposed incinerator[116] typify the anti-incinerator movement in China. People took to the streets to force the local government to move the location of the proposed incinerator.[117] The protests were met with violence from the police.[118] Other examples of environmental action include the China PX protest and the Qidong Protest of 2012. Residents of Qidong were successful in protesting a pipeline from the Japanese Oji Paper Company.[119] The organizers framed “their collective actions in opposition to Oji Paper and even the Japanese.”[120] This played on the anti-Japanese sentiment in China.[121] It also deflected blame away from the government.[122] Shifting blame away from the government, “reduced the chance of activists’ protest being repressed.”[123] Being aware of possible repression is important when engaging in any kind of action in China.[124]

See also[]

- Anti-incinerator movement in China

- Chinadialogue

- Dongtan, Chinese ecocity

- (China environment expert)

- Environment of China

- Environmental issues with the Three Gorges Dam

- Environmental policy in China#Soil pollution

- Hydrogen economy

- Leapfrogging from natural gas to hydrogen

- Tan Kai

- Wu Lihong

References[]

- ^ "Environmental Performance Index | Environmental Performance Index".

- ^ China Weighs Environmental Costs; Beijing Tries to Emphasize Cleaner Industry Over Unbridled Growth After Signs Mount of Damage Done Archived 30 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine 23 July 2013

- ^ Keith Bradsher (4 July 2012). "Bolder Protests Against Pollution Win Project's Defeat in China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ "Environmental Protests Expose Weakness In China's Leadership". Forbes Asia. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ John Upton (8 March 2013). "Pollution spurs more Chinese protests than any other issue". Grist.org. Grist Magazine, Inc. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "China's Evolving Environmental Protection Laws - Environment - China".

- ^ "China Has Successfully Improved Air Quality, but the Efforts Could Unmask Further Global Warming".

- ^ "China Has Successfully Improved Air Quality, but the Efforts Could Unmask Further Global Warming".

- ^ Frankfurt School – UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance (2018). Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2018. Available online at: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/unep/documents/global-trends-renewable-energy-investment-2018

- ^ "Commentary: China will bet big on clean energy to achieve carbon neutrality".

- ^ Water Demands of Coal-Fired Power Drying Up Northern China Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine 25 March 2013 Scientific American

- ^ On China's Electricity Grid, East Needs West—for Coal Archived 15 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine 21 March 2013 BusinessWeek

- ^ Chinese Utilities Face $20 Billion Costs Due to Water, BNEF Says 24 March 2013 BusinessWeek

- ^ China says more than half of its groundwater is polluted Archived 18 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian 23 April 2014

- ^ "China's water contains dangerous amounts of a cancer-causing agent NDMA". WebMD China. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "China's forest coverage exceeds target ahead of schedule". Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Liu, Jianguo and Jordan Nelson. "China's environment in a globalizing world", Nature, Vol. 434, pp. 1179-1186, 30 June 2005.'.' Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ "International Effort To Save Forests Should Target 15 Countries," Archived 12 September 2009 at the Library of Congress Web Archives United Nations Environment Program, 20 August 2001.'.' Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ "China's Threatened Forest Regions". Pulitzer Center. 12 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ "Three Gorges Dam | International Rivers". 5 May 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "No Casualties in Three Gorges Dam Landslide". 23 May 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ UNDP/GEF. (2007) The Yellow Sea: Analysis of Environmental Status and Trends. p. 408, Ansan, Republic of Korea.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murray N. J., Clemens R. S., Phinn S. R., Possingham H. P. & Fuller R. A. (2014) Tracking the rapid loss of tidal wetlands in the Yellow Sea. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12, 267-72. doi: 10.1890/130260

- ^ MacKinnon, J.; Verkuil, Y.I.; Murray, N.J. (2012), IUCN situation analysis on East and Southeast Asian intertidal habitats, with particular reference to the Yellow Sea (including the Bohai Sea), Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 47, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN, p. 70, ISBN 9782831712550, archived from the original on 24 June 2014

- ^ HAN, Jun "EFFECTS OF INTEGRATED ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT ON LAND DEGRADATION CONTROL AND POVERTY REDUCTION." Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Workshop on Environment, Resources and Agricultural Policies in China, 19 June 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Penguin Books, 2005 and 2011 (ISBN 9780241958681). See chapter 12 entitled "China, Lurching Giant" (pages 258-377).

- ^ Feng, Hao (14 September 2017). "Yaks unleashed in fight against desertification". China Dialogue. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Kan, Haidong (February 2011). "Climate Change and Human Health in China". Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (2): A60-1. doi:10.1289/ehp.1003354. PMC 3040620. PMID 21288808.

- ^ Strauss, Benjamin; Kulp, Scott. "20 Countries Most At Risk From Sea Level Rise". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Dorje, Yeshi. "Researchers: Tibetan Glacial Melt Threatens Billions". VOA. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Edward Wong (29 March 2013). "Cost of Environmental Damage in China Growing Rapidly Amid Industrialization". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "2 Major Air Pollutants Increase in Beijing". The New York Times. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ John Upton (25 July 2013). "China to spend big to clean up its air". Grist.org. Grist Magazine, Inc. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Wong, Edward (17 August 2016). "Coal Burning Causes the Most Air Pollution Deaths in China, Study Finds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Bloomberg News (14 January 2013). "Beijing Orders Official Cars Off Roads to Curb Pollution". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "China's largest algal bloom turns the Yellow Sea green". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Liu, D.; et al. (2009), "World's largest macroalgal bloom caused by expansion of seaweed aquaculture in China.", Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58 (6): 888–895, doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.01.013, PMID 19261301

- ^ Xinhua News, "Car ownership tops 154 million in China in 2014 Archived 24 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine," 27 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wernick, Adam (19 March 2019). "China announces a new ban on single-use plastics". The World. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Economy, Elizabeth (17 July 2015). "The Environmental Problem China Can No Longer Overlook". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "The River Runs Black". Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Cancer in China". Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tobias, Michael Charles (2 November 2012). "Animal Rights In China". Forbes. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Yee, Amy (28 January 2013). "Market for Bear Bile Threatens Asian Population". New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Jackie Chan PSA on Bear Bile Farming". World Animal Protection US. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "Animal Rights In China Get Boost From Celebrity Activists And Shifting Attitudes". Huffington Post. 22 April 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Loo, Daryl (16 February 2012). "Chinese Celebrities Oppose IPO for Operator of Bear-Bile Farm". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Melanie Hart; Jeffrey Cavanagh (20 April 2012). "Environmental Standards Give the United States an Edge Over China". Center for American Progress. Center for American Progress. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Ma Jun (31 January 2007). "How participation can help China's ailing environment". ChinaDialogue. ChinaDialogue. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Environmental Activists Detained in Hangzhou". Human Rights in China. Human Rights in China. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Joseph Kahn & Jim Yardley (26 August 2007). "As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Fullerton, John (2 May 2015). "China: Ecological Civilization Rising?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jennifer Duggan (25 April 2014). "China's polluters to face large fines under law change". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "China Revises Environmental Law". Voice of America. 25 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "China Solar Stocks Are Surging After Xi's 2060 Carbon Pledge". Bloomberg.com. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "China going carbon neutral before 2060 would lower warming projections by around 0.2 to 0.3 degrees C". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "China seeks better protection of Yangtze river with landmark law". Reuters. 30 December 2020.

- ^ “Protection of forests and control of desertification” Archived 27 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ Li, Zhiyong. ”A policy review on watershed protection and poverty alleviation by the Grain for Green Programme in China” Archived 16 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ^ Stanway, David; Perry, Michael (5 January 2018). "China to create new forests covering area size of Ireland: China Daily". Reuters. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "China announces huge reforestation plans". Climate Action. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Li, Weida. "China to increase forest coverage to 23 percent by 2020". GBTimes. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "China boosts forest cover amid greening campaign". Xinhua. 12 July 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "China proposes updated NDC targets". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Standaert, Michael (19 July 2020). "China's first climate striker warned: give it up or you can't go back to school". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Ratliff, Evan (April 2003). "The Green Wall Of China". Wired Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (9 February 2016). "'Wrong type of trees' in Europe increased global warming". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friedlingstein et al. 2019, Table 7.

- ^ "China". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "China going carbon neutral before 2060 would lower warming projections by around 0.2 to 0.3 degrees C". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "China, the world's top global emitter, aims to go carbon-neutral by 2060". ABC News. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "China's top climate scientists unveil road map to 2060 goal". Bloomberg. The Japan Times. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "China's top climate scientists map out path to 2060 goal". JWN. Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "New momentum reduces emissions gap, but huge gap remains - analysis". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ ChinaFAQs: China’s Energy Conservation Accomplishments of the 11th Five Year Plan, ChinaFAQs on 25 July 2011, http://www.chinafaqs.org/library/chinafaqs/chinas-energy-conservation-accomplishments-11th-five-year-plan Archived 28 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Adapting to Floods by Creating "Sponge Cities" in China". Climate Adaptation Platform. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Harris, Mark (1 October 2015). "China's sponge cities: soaking up water to reduce flood risks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ "What is a Sponge City?". Simplicable. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Biswas, Asit K.; Hartley, Kris. "China's 'sponge cities' aim to re-use 70% of rainwater – here's how". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Jill (7 April 2014). "China's Rapidly Growing Animal Welfare Movement". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (6 March 2013). "Amid Suffering, Animal Welfare Legislation Still Far Off in China". New York Times Blogs. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ "China". World Animal Protection. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "A small voice calling". The Economist. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Matthew, Bossons. "New Meat: Is China Ready for a Plant-Based Future?". That's. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Milman, Oliver; Leavenworth, Stuart (20 June 2016). "China's plan to cut meat consumption by 50% cheered by climate campaigners". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "China to force firms to report use of plastic in new recycling push". Reuters. 30 November 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 102. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Yanhua, Deng; Guobin, Yang (2013). "Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context". The China Quarterly. 214: 322. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000659. S2CID 154428459.

- ^ Ronggui, Huang; Xiaoyi, Sun (2020). "Dual Mediation and Success of Environmental Protests in China: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of 10 Cases". Social Movement Studies. 19 (4): 411. doi:10.1080/14742837.2019.1682539. S2CID 210461780.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 146.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 144.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 144.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 145.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 156–157.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 157.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 157.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 156.

- ^ EJatlas (2018). "Controversy Over the Development of the Nujiang Dams, China". Environmental Justice Atlas. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (2 December 2016). "Joy as China Shelves Plans to Dam 'Angry River". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 152.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 152–153.

- ^ Cheung, Ray (17 June 2004). "Greens' United Voice Shifts Policy in Right Direction". South China Morning Post.

- ^ Cheung, Ray (17 June 2004). "Greens' United Voice Shifts Policy in Right Direction". South China Morning Post.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 104. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 116. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Yanhua, Deng; Guobin, Yang (2013). "Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context". The China Quarterly. 214: 328. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000659. S2CID 154428459.

- ^ Yanhua, Deng; Guobin, Yang (2013). "Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context". The China Quarterly. 214: 322. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000659. S2CID 154428459.

- ^ Yanfei, Sun; Dingxin, Zhao (2008). "Environmental Campaigns". Popular Protest in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 150.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 105. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 102–103. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Yanhua, Deng; Guobin, Yang (2013). "Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context". The China Quarterly. 214: 322. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000659. S2CID 154428459.

- ^ Yanhua, Deng; Guobin, Yang (2013). "Pollution and Protest in China: Environmental Mobilization in Context". The China Quarterly. 214: 322. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000659. S2CID 154428459.

- ^ EJatlas (2019). "Chenjiachong Landfill Site and the Proposed Waste-to-Energy Plant in Yangluo Wuhan, Hubei, China". Environmental Justice Atlas. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (5 July 2019). "Protests Over Incinerator Rattle Officials in Chinese City". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Beijing Bureau (8 July 2019). "Wuhan Protests: Incinerator Plan Sparks Mass Unrest". BBC News. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Brock, Kendra (4 July 2019). "Environmental Protest Breaks Out in China's Wuhan City". The Diplomat. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 102. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Lu, Jian; Chan, Chris King-Chi (2016). "Collective Identity, Framing and Mobilisation of Environmental Protests in Urban China: A Case Study of Qidong's Protest". China: An International Journal. 14 (2): 120. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

Further reading[]

| Library resources about Environmental issues in China |

- Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Penguin Books, 2005 and 2011 (ISBN 9780241958681). See chapter 12 entitled "China, Lurching Giant" (pages 258–377).

- Elizabeth Economy. The River Runs Black. Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Judith Shapiro. [1]. China's Environmental Challenges. Polity Books, 2012.

- Judith Shapiro. Mao's War Against Nature. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Jianguo Liu and Jared Diamond, "China's environment in a globalizing world", Nature, volume 435, pages 1179–1186, 30 June 2005.

- Shunsuke Managi and Shinji Kaneko. Chinese Economic Development and the Environment (Edward Elgar Publishing; 2010) 352 pages; Analyzes the driving forces behind trends in China's CO2 emissions.

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Development Programme, "Environment and People’s Health in China", 2001

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme, "Indoor air pollution database for China", Human Exposure Assessment Series, 1995.

- Rachel E. Stern. Environmental Litigation in China: A Study in Political Ambivalence (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

- Joanna Lewis. Green Innovation in China: China's Wind Power Industry and the Global Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy (Columbia University Press 2015)

- Anna Lora-Wainwright. Fighting for Breath: Living Morally and Dying of Cancer in a Chinese Village (University of Hawaii Press, 2013)

External links[]

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2013) |

- Organizations

- chinadialogue the bilingual source of high-quality news, analysis and discussion on all environmental issues, with a special focus on China.

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People's Republic of China

- Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences

- China Environmental Protection Foundation

- China Environmental Protection Union (the "All-China Environmental Federation")

- The Global Environmental Institute (GEI) is a Chinese non-profit, non-governmental organization that was established in Beijing, China in 2004

- The Beijing Energy Network (BEN or 北京能源网络) is a grassroots organization based in Beijing

- Greenpeace China Up to date information on China's Environment

- Articles

- China's Environmental Crisis - News collections on China's environment

- Cleaner Greener China - Website on China's environmental issues, policies, NGOs, and products

- 2005 Interview with Pan Yue, China' deputy environment minister

- Chinese environmental activist on climate change

- China Green News - Beijing-based NGO providing summaries and translations of domestic environmental news.

- China’s Environmental Movement

- Air Pollution in China A flash animation assessing air degree of pollution in China

- A Short History of China's Fragile Environment

- Green Group Warns China of Glacier Retreat Threat

- An Assessment of the Economic Losses Resulting from Various Forms of Environmental Degradation in China

- Coming of Age: China’s Environmental Awareness Gains Momentum - Greenpeace China

- Can China Catch a Cool Breeze? by Christian Parenti, The Nation, 15 April 2009

- The Green Reason - greening the Olympics

- Videos

- "The Environmental Challenge to China's Future", Dr. Elizabeth Economy (2010)

- Environmental issues in China