History of New Brunswick

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Canada |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

| Historically significant |

|

| Topics |

|

| By provinces and territories |

|

| See also |

|

The history of New Brunswick covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day New Brunswick were inhabited for millennia by the several First Nations groups, most notably the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, and the Passamaquoddy.

French explorers first arrived to the area during the 16th century, and began to settle the region in the following century, as a part of the colony of Acadia. By the early 18th century, the region experienced an influx of Acadian refugees moving into the area, after the French surrendered their claim to Nova Scotia in 1713. Many of these Acadians were later forcibly expelled from the region by the British during the Seven Years' War. The resulting conflict also saw the French cede its remaining claims to continental North America to the British, including present-day New Brunswick. In the first two decades under British-rule, the region was administered as a part of the colony of Nova Scotia. However, in 1784, the western portions were severed from the rest of Nova Scotia to form the new the colony the New Brunswick; partly in response to the influx of loyalists that settled British North America after the American Revolutionary War. During the 19th century, New Brunswick saw an influx of settlers that included formerly deported Acadians, Welsh migrants, and a large number of Irish migrants.

Efforts to establish a Maritime Union during the 1860s eventually resulted in Canadian Confederation, with New Brunswick being united with Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada to form a single federation in July 1867. The province of New Brunswick experienced an economic downturn during the late 19th century, although its economy began to expand again in the early 20th century. During the 1960s, the government embarked on an equal opportunity program that rectified inequities experienced by the province's French-speaking population. By 1969, New Brunswick was officially designated as bilingual English and French province under the New Brunswick Official Languages Act

Early history[]

The First Nations of New Brunswick include the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet/Wəlastəkwiyik and Passamaquoddy. The Mi'kmaq territories are mostly in the east of the province. The Maliseets are located along the length of the St. John River, and the Passamaquoddy are situated in the southwest, around Passamaquoddy Bay. Amerindians have occupied New Brunswick for at least 13,000 years.

Maliseet[]

The "Maliseet" (also known as Wəlastəkwiyik, and in French as Malécites or Étchemins (the latter collectively referring to the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy)) are a First Nations people who inhabit the St. John River valley and its tributaries, extending to the St. Lawrence in Quebec. Their territory included the entire watershed of the St. John River on both sides of the International Boundary between New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada, and Maine in the United States.

Wəlastəkwiyik is the name (and Maliseet spelling) for the people of the St. John River, and Wəlastəkwey is their language. (Wolastoqiyik is the Passamaquoddy spelling of Wəlastəkwiyik.) Maliseet is the name by which the described the Wəlastəkwiyik to early Europeans since the Wəlastəkwey language seemed to the Mi'kmaq to be a slower version of the Mi'kmaq language. The Wəlastəkwiyik so named themselves because their territory and existence centred on the St. John River which they called the Wəlastəkw. It meant simply "good river" for its gentle waves; "wəli" = good or beautiful, shortened to "wəl-" when used as modifier; "təkw" = wave; "-iyik" = the people of that place. Wəlastəkwiyik therefore means People of the Good [Wave] River, in their own language.

Before contact with the Europeans, the traditional culture of both the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy generally involved downriver in the spring to fish and plant crops, largely of corn (maize), beans, squash, and to hold annual gatherings. Then they travelled to the saltwater for the summer, where they harvested seafoods and berries. In the early autumn they travelled upstream to harvest their crops and prepare for the winter. After the harvest, they dispersed in small family groups to their hunting grounds at the headwaters of the various tributaries to hunt and trap during the winter.

Passamaquoddy[]

The Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati or Pestomuhkati in the Passamaquoddy language) are a First Nations people who live in northeastern North America, in Maine and New Brunswick.

Like the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy maintained a migratory existence, but in the woods and mountains of the coastal regions along the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine and along the St. Croix River and its tributaries. They dispersed and hunted inland in the winter; in the summer, they gathered more closely together on the coast and islands and farmed corn, beans, and squash, and harvested seafood, including porpoise.

The name Passamaquoddy is an anglicization of the Passamaquoddy word Peskotomuhkatiyik, the name they applied to themselves. Peskotomuhkat literally means "pollock-spearer", reflecting the importance of this fish.[1] Like the Maliseet, their method of fishing was spear-fishing rather than angling.

The Passamaquoddy were moved off land repeatedly by European settlers since the 16th century and were eventually confined in the United States to two reservations, one at Indian Township near Princeton and the other at Sipayik, between Perry and Eastport in eastern Washington County, Maine. The Passamaquoddy also live in Charlotte County, New Brunswick, and have recently acquired legal status in Canada as a First Nation. They are currently pursuing the return of lands in the county, including Ktaqamkuk, their name for St. Andrews, New Brunswick which was the ancestral capital of the Passamaquoddy.

Mi'kmaq[]

The Mi'kmaq (previously spelled Micmac in English texts) are a First Nations people, indigenous to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspe peninsula in Quebec and the eastern half of New Brunswick in the Maritime Provinces. Míkmaw is the name of their language and the adjective form of Míkmaq.

In 1616 Father Biard believed the Mi'kmaq population to be in excess of 3,000. However, he remarked that, because of European diseases, including smallpox, there had been large population losses in the previous century.

Wabanaki Confederacy[]

During the colonial wars the Mi'kmaq were allies with the four Abenaki nations [Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Maliseet], forming the Wabanaki Confederacy, pronounced [wɑbɑnɑːɣɔdi]. At the time of contact with the French (late 16th century) they were expanding from their Maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /St. Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquoian peoples, hence the Mi'kmaq name for this peninsula, Gespeg ("last-acquired").

They were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst, but as France lost control of Acadia in the 18th century, they soon found themselves overwhelmed by British (English, Irish, Scottish, Welsh) who seized much of the land without payment and deported the French. Later on the Mi'kmaq also settled Newfoundland as the unrelated Beothuk tribe became extinct.

Norse exploration[]

It is generally accepted by Norse scholars that Vikings explored the coasts of Atlantic Canada, including New Brunswick, during their stay in Vinland where their base was possibly at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, around the year 1000. Wild walnut (butternut) shells found at l'Anse aux Meadows suggest that the Vikings did indeed explore further along the Atlantic Coast. Butternut trees do not now grow in Newfoundland, but recent studies suggest that due to environmental changes butternuts may have grown in Newfoundland around the year 1000-1001 AD.[2]

French colonial era[]

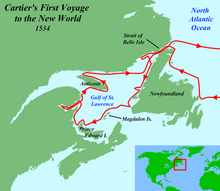

The first recorded European exploration of present-day New Brunswick was by French explorer Jacques Cartier in 1534, who discovered and named the Baie des Chaleurs between northern New Brunswick and the Gaspé peninsula of Quebec.

The next French contact was in 1604, when a party led by Pierre Dugua (Sieur de Monts) and Samuel de Champlain sailed into Passamaquoddy Bay and set up a camp for the winter on St. Croix Island at the mouth of the St. Croix River. 36 out of the 87 members of the party died of scurvy by winter's end and the colony was relocated across the Bay of Fundy the following year to Port-Royal in present-day Nova Scotia. Gradually, other French settlements were destroyed and seigneuries were founded. These were located along the Saint John River and present-day Saint John (including Fort La Tour and Fort Anne), the upper Bay of Fundy (including a number of villages in the Memramcook and Petitcodiac river valleys and the Beaubassin region at the head of the bay), and St. Pierre, (founded by Nicolas Denys) at the site of present-day Bathurst on the Baie des Chaleurs.

The whole region of New Brunswick (as well as Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and parts of Maine) were at that time proclaimed to be part of the royal French colony of Acadia. The French maintained good relations with the First Nations during their tenure and this was principally because the French colonists kept to their small coastal farming communities, leaving the interior of the territory to the aboriginals. This good relationship was bolstered by a healthy fur trading economy.

A competing British (English and Scottish) claim to the region was made in 1621, when Sir William Alexander was granted, by James VI & I, all of present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and part of Maine. The entire tract was to be called '"Nova Scotia", Latin for "New Scotland". Naturally, the French did not take kindly to the British claims. France however gradually lost control of Acadia in a series of wars during the 18th century.

17th century[]

Acadian Civil War[]

Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as the Acadian Civil War. The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was stationed.[3]

In the war, there were four major battles. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.[4] In response to the attack, D'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five-month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated (1643). La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.[5] After d'Aulnay died (1650), La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

King Williams War[]

The Maliseet from their headquarters at Meductic on the Saint John River, participated in numerous raids and battles against New England during King William's War.

18th century[]

One of its provisions of the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, which formally ended the Queen Anne's War, was that the French surrendered any claim to peninsular Acadia to the British Crown. All of what later became New Brunswick, as well as "Île St-Jean" (Prince Edward Island) and "Île Royale" (Cape Breton Island) would remain under French control. A number of Acadians that resided within Nova Scotia fled to these French-controlled peripheries of Acadia as a part of the Acadian Exodus.

The bulk of the Acadian population now found itself residing in the new British colony of Nova Scotia. The remainder of Acadia (including the New Brunswick region) was only lightly populated, with major Acadian settlements in New Brunswick only found at Beaubassin (Tantramar) and the nearby region of Shepody, Memramcook, and Petitcodiac, which they called Trois-Rivière,[6] as well as in the Saint John River valley at Fort la Tour (Saint John) and Fort Anne (Fredericton).

To defend the area, the French built Fort Nashwaak, Fort Boishebert, Fort Menagoueche in Bay of Fundy, and in the southeast Fort Gaspareaux and Fort Beauséjour. The latter was captured by British and New England troops in 1755, followed soon after by the Expulsion of the Acadians. Although contentintal Acadia remained in French control, peninsular Acadia passed into British hands with the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), but the new owners were slow to occupy their new possession. Until the definitive peace in the Americas occasioned by the Treaty of Paris (1763), the region was subject to low-grade contention.

The Maliseet from their headquarters at Meductic on the Saint John River, participated in numerous raids and battles against New England during Father Rale's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, a conflict between the Acadian and Mi'kmaq militias, and the British, numerous raids and battles occurred on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

Seven Years' War[]

Prior to 1755, Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[7] During the French and Indian War, the British sought both to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[8]

After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the second wave of the Expulsion of the Acadians began. Moncton was sent on the St. John River Campaign and the Petitcodiac River Campaign. Commander Rollo accomplished the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign. And Wolfe was sent on the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758), the British wanted to clear the Acadians from the villages along the Gulf of St. Lawrence to prevent any interference with the Siege of Quebec (1759).[9] Fort Anne fell during the St. John River Campaign and following this, all of present-day New Brunswick came under British control. France ultimately lost control of all of its North American territories by 1760. In the Treaty of Paris (1763), which put a close to the wider hostilities between Britain, France and Spain, was recognised the eviction of France from North America.

British colonial era[]

After the Seven Years' War, most of what is now New Brunswick (and parts of Maine) was incorporated into the colony of Nova Scotia as Sunbury County (county seat – Campobello). New Brunswick's relative location away from the Atlantic coastline hindered new settlement during the immediate post war period. There were a few notable exceptions, such as the founding of "The Bend" (present-day Moncton) in 1766 by Pennsylvania Dutch settlers sponsored by Benjamin Franklin's Philadelphia Land Company.[citation needed]

Other American settlements developed, principally in former Acadian lands in the southeast region, especially around Sackville. An American settlement also developed at Parrtown (Fort la Tour) at the mouth of the Saint John River. English settlers from Yorkshire also arrived in the Tantramar region near Sackville prior to the Revolutionary War.

American Revolution[]

The American Revolutionary War had a direct effect on the New Brunswick region, with several conflicts occurring in the region including the Maugerville Rebellion (1776), the Battle of Fort Cumberland, Siege of Saint John (1777) and the Battle at Miramichi (1779). Significant population growth would not occur until after the American Revolution, when Britain convinced refugee Loyalists from New England to settle in the area by giving them free land. Some earlier American settlers in New Brunswick actually favoured the colonial revolutionary cause.[10] In particular, Jonathan Eddy and his militia harassed and laid siege to the British garrison at Fort Cumberland (the renamed Fort Beausejour) during the early parts of the American Revolution. It was only after the arrival of a relief force from Halifax that the siege was lifted.

The Loyalists and the establishment of New Brunswick[]

With the arrival of the Loyalist refugees in Parrtown (Saint John) in 1783,[11] the need to politically organize the territory became acute. The newly arrived Loyalists felt no allegiance to Halifax and wanted to separate from Nova Scotia to isolate themselves from what they felt to be democratic and republican influences existing in that city. They felt that the government of Nova Scotia represented a Yankee population which had been sympathetic to the American Revolutionary movement, and which disparaged the intensely anti-American, anti-republican attitudes of the Loyalists. "They [the loyalists]," Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote from Saint John, New Brunswick, December 28, 1786, "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were. This makes me much doubt their remaining long dependent."[12] These views undoubtedly were exaggerated but there was no love lost between the Loyalists and the Halifax establishment and the feelings of the newly arrived Loyalists helped to sow the seeds for partition of the colony.

The election of 1786 was bitterly contested and pitted two concepts of loyalty to the Empire against one another: loyalty to the King and his appointed governors, and loyalty to the King with local affairs handled by the locals. Hundreds who protested a rigged election and signed a petition to call another election were arrested for sedition: the issue of what loyalty meant was at the centre of Canadian 19th century politics.[13] This event replicated the pre-1775 behavior and attitude of both Tories and Whigs in the southern 13 Colonies who protested their loyalty to the King and pride in belonging to the British Empire while insisting on their rights as British subjects, local rule and fair governance.[14]

The British administrators of the time, for their part, felt that the colonial capital (Halifax) was too distant from the developing territories to the west of the Isthmus of Chignecto to allow for proper governance and that the colony of Nova Scotia therefore should be split. As a result, the colony of New Brunswick was officially created with Sir Thomas Carleton the first governor on August 16, 1784.

New Brunswick was named in honour of the British monarch, King George III, who was descended from the House of Brunswick (Haus Braunschweig in German, derived from the city of Braunschweig, now Lower Saxony). Fredericton, the capital city, was likewise named for George III's second son, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. This was, however, despite local recommendations to be called 'New Ireland'[15]

The choice of Fredericton (the former Fort Anne) as the colonial capital shocked and dismayed the residents of the larger Parrtown (Saint John). The reason given was because Fredericton's inland location meant it was less prone to enemy (i.e. American) attack. Saint John did, however, become Canada's first incorporated city and for over a century was one of the dominant communities in British North America. Saint John in 1787–91 was home to the former American general Benedict Arnold, who defected to the British army. He was an aggressive businessman who sued a great deal and had a negative reputation by the time he quit and went to London.[16]

19th century[]

Some deported Acadians from Nova Scotia found their way back to "Acadie" during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They settled mostly in coastal regions along the eastern and northern shores of the new colony of New Brunswick. There they lived in relative (and in many ways self-imposed) isolation as they tried to maintain their language and traditions.

The War of 1812 had little effect on New Brunswick proper. There was however some action on the waters of the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine by privateers and small vessels of the British navy.[17] Forts such as the Carleton Martello Tower in Saint John and the St. Andrew's Blockhouse on Passamaquoddy Bay were constructed, but no action was seen. Locally, New Brunswickers were on good terms with their neighbours in Maine as well as the rest of New England, who generally did not support the war. There was even one incident during the war where the town of St. Stephen lent its supplies of gunpowder to neighbouring Calais, Maine, across the St. Croix River, for the local Fourth of July Independence Day celebrations.

That being said, New Brunswick's contribution to the war effort in Upper Canada was significant in terms of troop contribution. In the winter of 1813, the locally mustered 104th Regiment of Foot (New Brunswick), the only regular regiment in the British Army raised outside the British Isles at the time, marched overland from Fredericton to Kingston, an epic journey documented in the war diary of John Le Couteur. Once in Upper Canada, the 104th fought in some of the most significant actions of the war, including the Battle of Lundy's Lane, the Siege of Fort Erie and the raid on Sacket's Harbour.

In 1819, the ship Albion left Cardigan for New Brunswick, carrying the first Welsh settlers to Canada; on board were 27 Cardigan families, many of whom were farmers.[18]

Border disputes[]

The Maine-New Brunswick frontier had not been defined by the Treaty of Paris (1783) which had concluded the Revolutionary War. The border was contested, and frequently this fact was taken advantage of by people on both sides of the border to engage in a lively smuggling trade, especially on the waters of Passamaquoddy Bay. The illicit trade in Nova Scotia gypsum resulted in the so-called "Plaster War" of 1820.[19]

By the 1830s competing lumber interests and immigration meant that a solution was required. The situation actually deteriorated sufficiently enough by 1842 that the governor of Maine called out his militia. This was followed by the arrival of British troops in the region shortly thereafter. The entire debacle, referred to as the Aroostook War, was bloodless – unless one counts the mauling by bears at the Battle of Caribou – and thankfully, cooler heads prevailed with the subsequent Webster-Ashburton Treaty settling the dispute. Some local residents in the Madawaska region did not care much one way or the other as to who would actually win control of the area. When one resident of Edmundston was asked by arbitrators which side he supported, he replied "the Republic of Madawaska". This name is still used today and describes the northwestern corner of the province.

Economy[]

Throughout the 19th century, shipbuilding, beginning in the Bay of Fundy with shipbuilders like James Moran in St. Martins and soon spreading to the Miramichi, became the dominant industry in New Brunswick. The ship Marco Polo, arguably the fastest clipper ship of her time was launched from Saint John in 1851. Noted shipbuilders like Joseph Salter laid the foundations of towns such as Moncton. Resource-based industries such as logging and farming were also important to the New Brunswick economy, despite disasters such as the 1825 Miramichi fire. From the 1850s through to the end of the century, several railways were built across the province, making it easier for these inland resources to make it to markets elsewhere.

Immigration[]

Immigration in the early part of the 19th century was mostly from the west country of England and from Scotland, but also from Waterford, Ireland having often come through or having lived in Newfoundland prior.

A large influx of Catholic settlers arrived in New Brunswick in 1845 from Ireland as a result of the Great Famine. They headed to the cities of Saint John or Chatham, which to this day calls itself the "Irish Capital of Canada". Established Protestants resented the newly arrived Catholics. Until the 1840s, Saint John, the major city of New Brunswick, was a largely homogenous, Protestant community. Combined with a decade of economic distress in New Brunswick, the immigration of poor unskilled labourers triggered a nativist response. The Orange Order, until then a small and obscure fraternal order, became the vanguard of nativism in the colony and stimulated Orange-Catholic tension. The conflict culminated in the riot of 12 July 1849, in which at least 12 people died. The violence subsided as Irish immigration declined.[20]

Irish migrants[]

In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland flooded into Saint John. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge waves of Famine refugees flooded these shores. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47," one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour. However, thousands of Irish were living in New Brunswick prior to these events, mainly in Saint John and the Miramichi River valley.

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.[21]

The Miramichi River valley, received a significant Irish immigration in the years before the Great Famine. These settlers tended to be better off and better educated than the later arrivals, who came out of desperation. Though coming after the Scottish and the French Acadians, they made their way in this new land, intermarrying with the Catholic Highland Scots, and to a lesser extent, with the Acadians. Some, like Martin Cranney, held elective office and became the natural leaders of their augmented Irish community after the arrival of the famine immigrants. The early Irish came to the Miramichi because it was easy to get to with lumber ships stopping in Ireland before returning to Chatham and Newcastle, and because it provided economic opportunities, especially in the lumber industry. They were commonly Irish speakers, and in the eighteen thirties and eighteen forties there were many Irish-speaking communities along the New Brunswick and Maine frontier.[22]

The Irish language survived as a community language in New Brunswick into the twentieth century. The 1901 census specifically enquired as to the mother tongue of the respondents, defining it as a language commonly spoken in the home. There were several individuals and a scattering of families in the census who described Irish as their first language and as being spoken at home. In other respects the respondents had less in common, some being Catholic and some Protestant.[23]

Canadian Confederation[]

New Brunswick was one of the four original provinces of Canada that entered into Confederation in 1867. The Charlottetown Conference of 1864 had originally been intended only to discuss a Maritime Union of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, but concerns over the American Civil War as well as Fenian activity along the border led to an interest in expanding the geographic scope of the union. This interest arose from the Province of Canada (formerly Upper and Lower Canada, later Ontario and Quebec) and a request was made by the Canadians to the Maritimers to have the meeting's agenda altered.

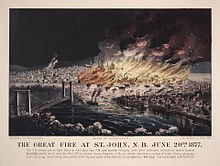

Following Confederation, the naysayers were proven right and New Brunswick (as well as the rest of the Maritimes) suffered the effects of a significant economic downturn. New national policies and trade barriers that had been created as a result of Confederation disrupted the historic trading relationship between the Maritime Provinces and New England. In 1871, the legislature sent a delegation to Ottawa in order to renew on "better terms".[24] The situation in New Brunswick was exacerbated by the Great Fire of 1877 in Saint John and by the decline of the wooden sailing shipbuilding industry. The global recession sparked by the Panic of 1893 significantly affected the local export economy. Many skilled workers lost their jobs and were forced to move west to other parts of Canada or south to the United States, but as the 20th Century dawned, the province's economy began to expand again. Manufacturing gained strength with the construction of several textile mills across the province and, in the crucial forestry sector, the sawmills that had dotted inland sections of the province gave way to larger pulp and paper mills. Nevertheless, unemployment remained relatively high and the Great Depression provided another setback. Two influential families, the Irvings and the McCains, emerged from the depression to begin to modernize and vertically integrate the provincial economy.

World War II[]

After Canada joined World War II, 14 army units were organized, in addition to The Royal New Brunswick Regiment,[25] and first deployed in the Italian campaign in 1943. After the Normandy landings they deployed to northwestern Europe, along with The North Shore Regiment.[25] The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a training program for ally pilots, established bases in Moncton, Chatham, and Pennfield Ridge, as well as a military typing school in Saint John. While relatively unindustrialized and before the war, New Brunswick became home to 34 plants on military contracts from which the province received over $78 million, while other production centre contributed to all areas of the war effort.[25]

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had promised no conscription, asked the provinces if they would release the government of said promise. New Brunswick voted 69.1% yes. The policy was not implemented until 1944, too late for many of the conscripts to be deployed.[25] New Brunswick sustained 1808 fatalities between the Army, RCAF, and RCN.[26]

Post World War II[]

The Acadians, who had mostly fended for themselves on the northern and eastern shores since they were allowed to return after 1764, were traditionally isolated from the English speakers that dominated the rest of the province. Government services were often not available in French, and the infrastructure in predominantly francophone areas was noticeably less evolved than in the rest of the province. This changed with the election of premier Louis Robichaud in 1960. He embarked on the ambitious Equal Opportunity Plan in which education, rural road maintenance, and health care fell under the sole jurisdiction of a provincial government that insisted on equal coverage of all areas of the province. Teachers were awarded equal rates of pay regardless of enrollment.

County councils were abolished with the rural areas outside cities, towns and villages coming under direct provincial jurisdiction. The 1969 New Brunswick Official Languages Act made French an official language, on par with English. Linguistic tensions rose on both sides, with the militant Parti Acadien enjoying brief popularity in the 1970s and Anglophone groups pushing to repeal language reforms in the 1980s, led by the Confederation of Regions Party. By the 1990s however linguistic tensions had mostly evaporated.

See also[]

- Military history of the Mi’kmaq People

- Military history of the Maliseet people

- Military history of the Acadians

- History of the Acadians

- Aboriginal communities in New Brunswick

- List of New Brunswick premiers

- List of New Brunswick lieutenant-governors

- Aboriginal place names in New Brunswick

- List of historic places in New Brunswick

- List of National Historic Sites of Canada in New Brunswick

- History of Moncton

- The Officers' Quarterly

General:

References[]

- ^ "Passamaquoddy - Maliseet Dictionary". Lib.unb.ca. 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ Fanny D. Bergen. "Popular American Plant-Names." The Journal of American Folklore 17: 89-106.

- ^ M. A. MacDonald, Fortune & La Tour: The civil war in Acadia, Toronto: Methuen. 1983

- ^ Dunn, Brenda (2004). A History of Port-Royal-Annapolis Royal, 1605-1800. Nimbus. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-55109-740-4.

- ^ Dunn (2004), p. 20.

- ^ Paul Surette, Memramckouke, Petcoudiac et la Reconstruction de l'Acadie - 1763-1806 Mamramcook, 1981, p. 9

- ^ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma Press. 2008

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction". In P.A. Buckner; Gail G. Campbell; David Frank (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation (3rd ed.). Acadiensis Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1.

• Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm. - ^ From Life of General the Honourable James Murray by R. H. Mahon, p. Page 70

- ^ admin (28 March 2014). "Chapter 3". unb.ca.

- ^ http://www.mocavo.com/History-of-New-Brunswick/102214/13 History of New Brunswick, Page 9

- ^ S.D. Clark, Movements of Political Protest in Canada, 1640–1840, (1959), pp. 150-51

- ^ David Bell, American Loyalists to New Brunswick, 2015 p. 23-24 ISBN 978-1-4595-0399-1

- ^ Maya Jasanoff, Liberty's Exiles, American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World, 2011, pp. 184-187 ISBN 978-1-4000-4168-8

- ^ "The Winslow Papers: The Partition of Nova Scotia".

- ^ Wilson, Barry (2001). Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 191ff. ISBN 978-0-7735-2150-6.

- ^ Smith, Joshua (2011). Battle for the Bay: The Naval War of 1812. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane Editions. pp. passim. ISBN 978-0-86492-644-9.

- ^ "2019 marks bi-centenary of the Albion sailing from Cardigan to Canada". Tivyside Advertiser. 28 April 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Smith, Joshua (2007). Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists, and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1780-1820. Gainesville, FL: UPF. pp. 95–108. ISBN 978-0-8130-2986-3.

- ^ Scott W. See, "The Orange Order and Social Violence in Mid-Nineteenth Century Saint John," Acadiensis 1983 13(1): 68-92

- ^ "Winslow Papers: The Partition of Nova Scotia". lib.unb.ca.

- ^ O’Driscoll & Reynolds (1988), p. 712.

- ^ "Culture - The Irish Language in New Brunswick - ICCANB". Newirelandnb.ca. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Stevenson 1871

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d New Brunswick at War. Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. 1995. pp. 1–13.

- ^ Bercuson, David J.; Granatstein, J.L. (1993). Dictionary Of Canadian Military History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195408478.

Further reading[]

- Acheson, Thomas W. (1993). Saint John: The Making of a Colonial Urban Community. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-5509-6.

- Andrew, Sheila (2002). "Gender and Nationalism: Acadians, Québécois, and Irish in New Brunswick Nineteenth-Century Colleges and Convent Schools, 1854-1888" (PDF). Historical Studies. Canadian Catholic Historical Association. 68: 7–23.

- Andrew, Sheila M. (1996). Development of Elites in Acadian New Brunswick, 1861-1881. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1508-6.

- Aunger, Edmund A. (1981). In Search of Political Stability: A Comparative Study of New Brunswick and Northern Ireland. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0366-3.

- Barkley, Murray (Spring 1975). "The Loyalist Tradition in New Brunswick: the Growth and Evolution of an Historical Myth, 1825-1914". Acadiensis. 4 (2): 3–45. JSTOR 30302493.

- Benedict, William H. (1925). New Brunswick in History. the author.

- Bell, David Graham (1983). Early Loyalist Saint John: The Origin of New Brunswick Politics, 1783-1786. New Ireland Press. ISBN 978-0-9690215-8-2.

- Deschamps, Isaac; Brenton, James (1784). The Perpetual Acts of the General Assemblies of His Majesty's Province of Nova Scotia: As Revised in the Year 1783. [1758-1783]. Halifax: Anthony Henry.

- Gair, W. Reavley (1985). A Literary and linguistic history of New Brunswick. Fiddlehead Poetry Books & Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 978-0-86492-052-2.

- Godfrey, W.G. (1983). "Carleton, Thomas". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- MacNutt, W. Stewart (1984). New Brunswick, a History: 1784-1867. Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 978-0-7715-9818-0.

- Mancke, Elizabeth (2005). The Fault Lines of Empire: Political Differentiation in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, Ca. 1760-1830. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95000-8.

- Marquis, Greg (Fall 2004). "Commemorating the Loyalists in the Loyalist City: Saint John, New Brunswick, 1883-1934". Urban History Review. 33 (1): 24–33. doi:10.7202/1015672ar. JSTOR 43560111.

- Nerbas, Don (June 2008). "Adapting to Decline: the Changing Business World of the Bourgeoisie in Saint John, NB, in the 1920s". Canadian Historical Review. 89 (2): 151–187. doi:10.3138/chr.89.2.151.

- Petrie, Joseph Richards (1944). Report of the New Brunswick Committee on Reconstruction. Fredericton.

- Richard, Chantal; Brown, Anne; Conrad, Margaret; et al. (2013). "Markers of Collective Identity in Loyalist and Acadian Speeches of the 1880s: A Comparative Analysis". Journal of New Brunswick Studies/Revue d'Études Sur le Nouveau-Brunswick. 4: 13–30.

- See, Scott W. (1993). Riots in New Brunswick: Orange nativism and social violence in the 1840s. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7770-7.

- Stewart, Ian (1994). Roasting Chestnuts: The Mythology of Maritime Political Culture. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-4273-0.

- Whitcomb, Edward A. (2010). A Short History of New Brunswick. Ottawa: From Sea To Sea Enterprises. ISBN 978-0-9865967-0-4.

- Whitelaw, William Menzies (1934). The Maritimes and Canada Before Confederation. Oxford University Press. excerpts

- Woodward, Calvin A. (1976). The history of New Brunswick provincial election campaigns and platforms, 1866-1974: With primary source documents on microfiche.

Older books[]

- Atkinson, Christopher William (1844). A Historical and Statistical Account of New-Brunswick, B.N.A.: With Advice to Emigrants. Edinburgh: Anderson & Bryce.–A Historical and Statistical Account of New-Brunswick at Google Books

- Fisher, Peter (1825). History of New Brunswick. Saint John: Chubb & Sears.– History of New Brunswick at Project Gutenberg

- Gesner, Abraham (1847). New Brunswick: With Notes for Emigrants. Comprehending the Early History, an Account of the Indians, Settlement ... London: Simmonds & Ward.–New Brunswick: With Notes for Emigrants at Google Books

- Hannay, James (1897). The Life and Times of Sir Leonard Tilley: Being a Political History of New Brunswick for the Past Seventy Years. Saint John.–The Life and Times of Sir Leonard Tilley at Google Books

- Lawrence, Joseph Wilson (1883). Foot-prints, Or, Incidents in Early History of New Brunswick. Saint John: J. & A. McMillan.–Foot-prints, Or, Incidents in Early History of New Brunswick at Google Books

- MacFarlane, W.G. (1895). New Brunswick Bibliography: The Books and Writers of the Province. Saint John: Sun Printing Company.–New Brunswick Bibliography at Google Books

- Report on Agriculture for the Province of New Brunswick. Fredericton: New Brunswick. Dept. of Agriculture. 1895.

- Perley, Moses Henry (1852). Reports on the Sea and River Fisheries of New Brunswick (second ed.). J. Simpson.–Reports on the Sea and River Fisheries of New Brunswick at Google Books

- Stevenson, Benjamin R. (1872). Report of the "Better Terms" Delegation of New Brunswick. Saint John: J. & A. McMillan.–Report of the "Better Terms" Delegation of New Brunswick at Google Books

- History of New Brunswick

- Acadian history