Hokkien

| Hokkien | |

|---|---|

| Minnan, 闽南话 | |

| 闽南话 / 閩南話 / 福建話 Bân-lâm-ōe / Bân-lâm-uē/ Hok-kiàn-uē | |

Koa-a books, Hokkien written in Chinese characters | |

| Region | East and Southeast Asia, specifically southern Fujian and other south-eastern coastal areas of China, Taiwan, Malaysia and Singapore |

| Ethnicity | Hoklo |

Native speakers | large fraction of 28 million Minnan speakers in mainland China (2018), 13.5 million in Taiwan (2017), 2 million in Malaysia (2000), 1.5 million in Singapore (2017),[1] 1 million in Philippines (2010)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Dialects | |

| Chinese script (see written Hokkien) Latin script (Pe̍h-ōe-jī) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | The Republic of China Ministry of Education and some NGOs are influential in Taiwan |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | hokk1242fuki1235 |

Distribution of Southern Min languages. Quanzhang (Hokkien) is dark green. | |

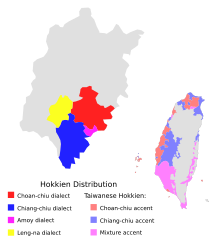

Distribution of Quanzhang (Minnan Proper) dialects within Fujian Province and Taiwan. Lengna dialect (Longyan Min) is a variant of Southern Min that is spoken near the Hakka speaking region in Southwest Fujian. | |

| Southern Min | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 閩南語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽南语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Hok-kiàn-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hoklo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 福佬話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 福佬话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Ho̍h-ló-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hokkien (/ˈhɒkiɛn/[7]) is a Southern Min language originating from the Minnan region in the south-eastern part of Fujian Province in Southeastern Mainland China and spoken widely there. It is also spoken widely in Taiwan (where it is usually known as Taiwanese); by the Chinese diaspora in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia; and by other overseas Chinese beyond Asia and all over the world. The Hokkien 'dialects' are not all mutually intelligible, but they are held together by ethnolinguistic identity. Taiwanese Hokkien is, however, mutually intelligible with the 2 to 3 million speakers of the Amoy (Xiamen) and Singaporean dialects, save for a few loanwords.[8]

In Southeast Asia, Hokkien historically served as the lingua franca amongst overseas Chinese communities of all dialects and subgroups, and it remains today as the most spoken variety of Chinese in the region, including in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines and some parts of Indochina (particularly Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).[9]

The Betawi Malay language, spoken by some five million people in and around the Indonesian capital Jakarta, includes numerous Hokkien loanwords due to the significant influence of the Chinese Indonesian diaspora, most of whom are of Hokkien ancestry and origin.

Names[]

Chinese speakers of the Quanzhang variety of Southern Min refer to the mainstream Southern Min language as

- Bân-lâm-gú / Bân-lâm-ōe (闽南语/闽南话; 閩南語/閩南話, literally 'language or speech of Southern Min') in China and Taiwan.[10]

- Tâi-gí (臺語, literally 'Taiwanese language') or Ho̍h-ló-ōe / Ho̍h-ló-uē (literally 'Hoklo speech') in Taiwan.

- Lán-nâng-ōe / Lán-lâng-ōe / Nán-nâng-ōe (咱人話 / 咱儂話, literally 'our people's speech') in the Philippines.

- Hok-kiàn-ōe (福建話, literally 'Hokkien speech') in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei.

In parts of Southeast Asia and in the English-speaking communities, the term Hokkien ([hɔk˥kiɛn˨˩]) is etymologically derived from the Southern Min pronunciation for Fujian (Chinese: 福建; pinyin: Fújiàn; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hok-kiàn), the province from which the language hails. In Southeast Asia and the English press, Hokkien is used in common parlance to refer to the Southern Min dialects of southern Fujian, and does not include reference to dialects of other Sinitic branches also present in Fujian such as the Fuzhou language (Eastern Min), Pu-Xian Min, Northern Min, Gan Chinese or Hakka. In Chinese linguistics, these languages are known by their classification under the Quanzhang division (Chinese: 泉漳片; pinyin: Quánzhāng piàn) of Min Nan, which comes from the first characters of the two main Hokkien urban centers of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou.

The word Hokkien first originated from Walter Henry Medhurst when he published the Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms in 1832. This is considered to be the earliest English-based Hokkien Dictionary and the first major reference work in POJ, although the romanization within was quite different from the modern system. In this dictionary, the word "Hok-këèn" was used. In 1869, POJ was further revised by John Macgowan in his published book A Manual Of The Amoy Colloquial. In this book, "këèn" was changed to "kien" and from then on, the word "Hokkien" began to be used more often.

Geographic distribution[]

Hokkien is spoken in the southern, seaward quarter of Fujian province, southeastern Zhejiang, and eastern Namoa Island in China; Taiwan; Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, Metro Davao and other cities in the Philippines; Singapore; Brunei; Medan, Riau and other cities in Indonesia; and from Taiping to the Thai border in Malaysia, especially around Penang.[8]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2018) |

Hokkien originated in the southern area of Fujian province, an important center for trade and migration, and has since become one of the most common Chinese varieties overseas. The major pole of Hokkien varieties outside of Fujian is nearby Taiwan, where immigrants from Fujian arrived as workers during the 40 years of Dutch rule, fleeing the Qing Dynasty during the 20 years of Ming loyalist rule, as immigrants during the 200 years of Qing dynasty rule, especially in the last 120 years after immigration restrictions were relaxed, and even as immigrants during the period of Japanese rule. The Taiwanese dialect mostly has origins with the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou variants, but since then, the Amoy dialect, also known as the Xiamen dialect, has become the modern prestige standard for the language in China. Both Amoy and Xiamen come from the Chinese name of the city (Chinese: 厦门; pinyin: Xiàmén; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ē-mûi); the former is from Zhangzhou Hokkien, whereas the latter comes from Mandarin.

There are many Minnan (Hokkien) speakers among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia as well as in the United States (Hoklo Americans). Many ethnic Han Chinese emigrants to the region were Hoklo from southern Fujian, and brought the language to what is now Burma (Myanmar), Vietnam, Indonesia (the former Dutch East Indies) and present day Malaysia and Singapore (formerly Malaya and the British Straits Settlements). Many of the Minnan dialects of this region are highly similar to Xiamen dialect (Amoy) and Taiwan Hokkien with the exception of foreign loanwords. Hokkien is reportedly the native language of up to 80% of the ethnic Chinese people in the Philippines, among which is known locally as Lán-nâng-uē or Lán-lâng-ōe or Nán-nâng-uē ("Our people's speech"). Hokkien speakers form the largest group of overseas Chinese in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines.[citation needed]

Classification[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Southern Fujian is home to three principal Minnan Proper (Hokkien) dialects: Chinchew, Amoy, Chiangchew, originating from the cities of Quanzhou, Xiamen and Zhangzhou (respectively).

Traditionally speaking, Quanzhou dialect spoken in Quanzhou is the Traditional Standard Minnan, it is the dialect that is used in and Liyuan Opera (梨园戏) and (南音). Being the Traditional Standard Minnan, Quanzhou dialect is considered to have the purest accent and the most conservative Minnan dialect.

In the late 18th to the early 19th century, Xiamen (Amoy) became the principal city of southern Fujian.[citation needed] Xiamen (Amoy) dialect is adopted as the Modern Standard Minnan. It is a hybrid of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. It has played an influential role in history, especially in the relations of Western nations with China, and was one of the most frequently learnt dialect of Quanzhang variety by Westerners during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

The Modern Standard form of Quanzhang accent spoken around the city of Tainan in Taiwan is a hybrid of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects, in the same way as the Amoy dialect. All Quanzhang dialects spoken throughout the whole of Taiwan are collectively known as Taiwanese Hokkien, or Holo locally, although there is a tendency to call these Taiwanese language for political reasons. It is spoken by more Taiwanese than any Sinitic language except Mandarin, and it is known by a majority of the population;[11] thus, from a socio-political perspective, it forms a significant pole of language usage due to the popularity of Holo-language media.

Southeast Asia[]

The varieties of Hokkien in Southeast Asia originate from these dialects.

The Chinese Singaporeans, Southern Malaysian Chinese, and Chinese Indonesians in Indonesia's Riau province and Riau Islands variant is from the Quanzhou area. They speak a distinct form of Quanzhou Hokkien called Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien (SPMH), where it is known as Singaporean Hokkien in Singapore.

Among Malaysian Chinese of Penang, and other states in Northern Peninsular Malaysia and ethnic Chinese Indonesians in Medan, with other areas in North Sumatra, Indonesia, a distinct form of Zhangzhou Hokkien has developed. In Penang, it is called Penang Hokkien while across the Malacca Strait in Medan, an almost identical variant is known as Medan Hokkien.

The Chinese Filipinos in the Philippines also speak a variant known as Philippine Hokkien, which is also mostly derived from Quanzhou Hokkien, particularly the Jinjiang and Nan'an dialects with a bit of influence from the Amoy (Xiamen) dialect, as most of their ancestors are also from the aforementioned areas.

History[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Variants of Hokkien dialects can be traced to two sources of origin: Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. Both Amoy and most Taiwanese are based on a mixture of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects, while the rest of the Hokkien dialects spoken in South East Asia are either derived from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, or based on a mixture of both dialects.

Quanzhou and Zhangzhou[]

During the Three Kingdoms period of ancient China, there was constant warfare occurring in the Central Plain of China. Northerners began to enter into Fujian region, causing the region to incorporate parts of northern Chinese dialects. However, the massive migration of northern Han Chinese into Fujian region mainly occurred after the Disaster of Yongjia. The Jìn court fled from the north to the south, causing large numbers of northern Han Chinese to move into Fujian region. They brought the Old Chinese spoken in the Central Plain of China from the prehistoric era to the 3rd century into Fujian.

In 677 (during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang), Chen Zheng, together with his son Chen Yuanguang, led a military expedition to suppress a rebellion of the She people. In 885, (during the reign of Emperor Xizong of Tang), the two brothers Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi, led a military expedition force to suppress the Huang Chao rebellion.[12] Waves of migration from the north in this era brought the language of Middle Chinese into the Fujian region.

Xiamen (Amoy)[]

The Amoy dialect is the main dialect spoken in the Chinese city of Xiamen (formerly romanized and natively pronounced as "Amoy") and its surrounding regions of Tong'an and Xiang'an, both of which are now included in the greater Xiamen area. This dialect developed in the late Ming dynasty when Xiamen was increasingly taking over Quanzhou's position as the main port of trade in southeastern China. Quanzhou traders began traveling southwards to Xiamen to carry on their businesses while Zhangzhou peasants began traveling northwards to Xiamen in search of job opportunities. A need for a common language arose. The Quanzhou and Zhangzhou varieties are similar in many ways (as can be seen from the common place of Henan Luoyang where they originated), but due to differences in accents, communication can be a problem. Quanzhou businessmen considered their speech to be the prestige accent and considered Zhangzhou's to be a village dialect. Over the centuries, dialect leveling occurred and the two speeches mixed to produce the Amoy dialect.

Early sources[]

Several playscripts survive from the late 16th century, written in a mixture of Quanzhou and Chaozhou dialects. The most important is the Romance of the Litchi Mirror, with extant manuscripts dating from 1566 and 1581.[13][14]

In the early 17th century, Spanish missionaries in the Philippines produced materials documenting the Hokkien varieties spoken by the Chinese trading community who had settled there in the late 16th century:[13][15]

- Diccionarium Sino-Hispanicum (1604), a Spanish–Hokkien dictionary, giving equivalent words, but not definitions.[16]

- Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china (1607), a Hokkien translation of the Doctrina Christiana.[17][18]

- Bocabulario de la lengua sangleya (c. 1617), a Spanish–Hokkien dictionary, with definitions.

- Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu (1620), a grammar written by a Spanish missionary in the Philippines.

These texts appear to record a Zhangzhou dialect, from the old port of Yuegang (modern-day Haicheng, an old port that is now part of Longhai).[19]

Chinese scholars produced rhyme dictionaries describing Hokkien varieties at the beginning of the 19th century:[20]

- Lūi-im Biāu-ngō͘ (Huìyīn Miàowù) (彙音妙悟 "Understanding of the collected sounds") was written around 1800 by Huang Qian (黃謙), and describes the Quanzhou dialect. The oldest extant edition dates from 1831.

- Lūi-chi̍p Ngé-sio̍k-thong Si̍p-ngó͘-im (Huìjí Yǎsútōng Shíwǔyīn) (彙集雅俗通十五音 "Compilation of the fifteen elegant and vulgar sounds") by Xie Xiulan (謝秀嵐) describes the Zhangzhou dialect. The oldest extant edition dates from 1818.

Walter Henry Medhurst based his 1832 dictionary on the latter work.

Phonology[]

Hokkien has one of the most diverse phoneme inventories among Chinese varieties, with more consonants than Standard Mandarin and Cantonese. Vowels are more-or-less similar to that of Standard Mandarin. Hokkien varieties retain many pronunciations that are no longer found in other Chinese varieties. These include the retention of the /t/ initial, which is now /tʂ/ (Pinyin 'zh') in Mandarin (e.g. 'bamboo' 竹 is tik, but zhú in Mandarin), having disappeared before the 6th century in other Chinese varieties.[21] Along with other Min languages, which are not directly descended from Middle Chinese, Hokkien is of considerable interest to historical linguists for reconstructing Old Chinese.

Finals[]

Unlike Mandarin, Hokkien retains all the final consonants corresponding to those of Middle Chinese. While Mandarin only preserves the n and ŋ finals, Southern Min also preserves the m, p, t and k finals and developed the ʔ (glottal stop).

The vowels of Hokkien are listed below:[22]

| Oral | Nasal | Stops | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | e | i | o | u | ∅ | m | n | ŋ | i | u | p | t | k | ʔ | ||

| Nucleus | Vowel | a | a | ai | au | ã | ãm | ãn | ãŋ | ãĩ | ãũ | ap | at | ak | aʔ | ||

| i | i | io | iu | ĩ | ĩm | ĩn | ĩŋ | ĩũ | ip | it | ik | iʔ | |||||

| e | e | ẽ | eŋ* | ek* | eʔ | ||||||||||||

| ə | ə | əm* | ən* | ə̃ŋ* | əp* | ət* | ək* | əʔ* | |||||||||

| o | o | oŋ* | ot* | ok* | oʔ | ||||||||||||

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ̃ | ɔm* | ɔn* | ɔ̃ŋ | ɔp* | ɔt* | ɔk | ɔʔ | ||||||||

| u | u | ue | ui | ũn | ũĩ | ut | uʔ | ||||||||||

| ɯ | ɯ* | ɯŋ | |||||||||||||||

| Diphthongs | ia | ia | iau | ĩã | ĩãm | ĩãn | ĩãŋ | ĩãũ | iap | iat | iak | iaʔ | |||||

| iɔ | ĩɔ̃* | ĩɔ̃ŋ | iɔk | ||||||||||||||

| iə | iə | iəm* | iən* | iəŋ* | iəp* | iət* | |||||||||||

| ua | ua | uai | ũã | ũãn | ũãŋ* | ũãĩ | uat | uaʔ | |||||||||

| Others | ∅ | m̩ | ŋ̍ | ||||||||||||||

(*)Only certain dialects

- Oral vowel sounds are realized as nasal sounds when preceding a nasal consonant.

- [õ] only occurs within triphthongs as [õãĩ].

The following table illustrates some of the more commonly seen vowel shifts. Characters with the same vowel are shown in parentheses.

| English | Chinese character | Accent | Pe̍h-ōe-jī | IPA | Teochew Peng'Im |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| two | 二 | Quanzhou, Taipei | lī | li˧ | jĭ (zi˧˥)[23] |

| Xiamen, Zhangzhou, Tainan | jī | ʑi˧ | |||

| sick | 病 (生) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | pīⁿ | pĩ˧ | pēⁿ (pẽ˩) |

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | pēⁿ | pẽ˧ | |||

| egg | 卵 (遠) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taiwan | nn̄g | nŋ˧ | nn̆g (nŋ˧˥) |

| Zhangzhou, Yilan[24] | nūi | nui˧ | |||

| chopsticks | 箸 (豬) | Quanzhou | tīr | tɯ˧ | tēu (tɤ˩) |

| Xiamen, Taipei | tū | tu˧ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | tī | ti˧ | |||

| shoes | 鞋 (街) | ||||

| Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | oê | ue˧˥ | ôi | ||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | ê | e˧˥ | |||

| leather | 皮 (未) | Quanzhou | phêr | pʰə˨˩ | phuê (pʰue˩) |

| Xiamen, Taipei | phê | pʰe˨˩ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | phôe | pʰue˧ | |||

| chicken | 雞 (細) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | koe | kue˥ | koi |

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | ke | ke˥ | |||

| hair | 毛 (兩) | Quanzhou, Taiwan, Xiamen | mn̂g | mŋ | mo |

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | mo͘ | mɔ̃ | |||

| return | 還 | Quanzhou | hoan | huaⁿ | huêng |

| Xiamen | hâiⁿ | hãɪ˨˦ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | hêng | hîŋ | |||

| Speech | 話 (花) | Quanzhou, Taiwan | oe | ue | |

| Zhangzhou | oa | ua |

Initials[]

Southern Min has aspirated, unaspirated as well as voiced consonant initials. For example, the word khui (開; "open") and kuiⁿ (關; "close") have the same vowel but differ only by aspiration of the initial and nasality of the vowel. In addition, Southern Min has labial initial consonants such as m in m̄-sī (毋是; "is not").

Another example is ta-po͘-kiáⁿ (查埔囝; "boy") and cha-bó͘-kiáⁿ (查某囝; "girl"), which differ in the second syllable in consonant voicing and in tone.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless Stop | plain | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced stop | oral or lateral | b (m) |

d~l (n) |

ɡ (ŋ) |

||

| (nasalized) | ||||||

| Affricate | plain | ts | ||||

| aspirated | tsʰ | |||||

| voiced | dz~l~ɡ | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Semi-vowels | w | j | ||||

- All consonants but ʔ may be nasalized; voiced oral stops may be nasalized into voiced nasal stops.

- Nasal stops mostly occur word-initially.[25]

- Quanzhou and nearby may pronounce dz as l or gl.[citation needed]

- Approximant sounds [w] [j], only occur word-medially, and are also realized as laryngealized [w̰] [j̰], within a few medial and terminal environments.[26]

Tones[]

According to the traditional Chinese system, Hokkien dialects have 7 or 8 distinct tones, including two entering tones which end in plosive consonants. The entering tones can be analysed as allophones, giving 5 or 6 phonemic tones. In addition, many dialects have an additional phonemic tone ("tone 9" according to the traditional reckoning), used only in special or foreign loan words.[27] This means that Hokkien dialects have between 5 and 7 phonemic tones.

Tone sandhi is extensive.[28] There are minor variations between the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou tone systems. Taiwanese tones follow the patterns of Amoy or Quanzhou, depending on the area of Taiwan.

| Tones | 平 | 上 | 去 | 入 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 陰平 | 陽平 | 陰上 | 陽上 | 陰去 | 陽去 | 陰入 | 陽入 | ||

| Tone Number | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 8 | |

| 調值 | Xiamen, Fujian | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˦ |

| 東 taŋ1 | 銅 taŋ5 | 董 taŋ2 | – | 凍 taŋ3 | 動 taŋ7 | 觸 tak4 | 逐 tak8 | ||

| Taipei, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˩˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Tainan, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˧ | ˦˩ | – | ˨˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Zhangzhou, Fujian | ˧˦ | ˩˧ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˩˨˩ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Quanzhou, Fujian | ˧˧ | ˨˦ | ˥˥ | ˨˨ | ˦˩ | ˥ | ˨˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

| Penang, Malaysia[29] | ˧˧ | ˨˧ | ˦˦˥ | – | ˨˩ | ˧ | ˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

Dialects[]

The Hokkien language (Minnan) is spoken in a variety of accents and dialects across the Minnan region. The Hokkien spoken in most areas of the three counties of southern Zhangzhou have merged the coda finals -n and -ng into -ng. The initial consonant j (dz and dʑ) is not present in most dialects of Hokkien spoken in Quanzhou, having been merged into the d or l initials.

The -ik or -ɪk final consonant that is preserved in the native Hokkien dialects of Zhangzhou and Xiamen is also preserved in the Nan'an dialect (色, 德, 竹) but are pronounce as -iak in Quanzhou Hokkien.[30]

- Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州閩南片):

- (安溪話)

- (德化話)

- Hui'an dialect (惠安話)

- Jinjiang dialect (晋江話)

- (南安話)

- (同安話)

- Quanzhou dialect (泉州話)

- Yongchun dialect (永春話)

- (尤溪話)

- (金門話)

- Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien (南馬福建話)

- Singaporean Hokkien (新加坡福建話)

- Philippine Hokkien (咱人話/咱儂話/菲律賓福建話)

- Zhangzhou Hokkien dialects (漳州閩南片):

- (龍溪話)

- Longyan dialect (龍巖話)

- (平和話)

- (雲霄話)

- (漳浦話)

- Zhangzhou dialect (漳州話)

- (詔安話)

- Haifeng dialect (海豐話)

- Lufeng dialect (陸豐話)

- Penang Hokkien (檳城/庇能福建話)

- Medan Hokkien (棉蘭福建話)

- hybrid Quanzhou–Zhangzhou:

- Amoy dialect (廈門話)

- Taiwanese Hokkien (臺灣話/臺灣閩南語/台語)

Comparison[]

The Amoy dialect (Xiamen) is a hybrid of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. Taiwanese is also a hybrid of these two dialects. Taiwanese in northern and coastal Taiwan tends to be based on the Quanzhou variety, whereas the Taiwanese spoken in central, south and inland Taiwan tends to be based on Zhangzhou speech. Meanwhile, Penang Hokkien and Medan Hokkien are based on the Zhangzhou dialect, whereas Philippine Hokkien and Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien, including Singaporean Hokkien, is based on the Quanzhou dialect. There are minor variations in pronunciation and vocabulary between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. The grammar is generally the same.

Additionally, extensive contact with the Japanese language has left a legacy of Japanese loanwords in Taiwanese Hokkien. On the other hand, the variants spoken in Singapore and Malaysia have a substantial number of loanwords from Malay and to a lesser extent, from English and other Chinese varieties, such as the closely related Teochew and some Cantonese. Meanwhile in the Philippines, there are also a few Spanish and/or Filipino (Tagalog) loanwords, while it is also currently a norm to frequently codeswitch with English and Filipino (Tagalog), or other Philippine languages, such as Bisaya.

Mutual intelligibility[]

The Quanzhou dialect, Xiamen dialect, Zhangzhou dialect and Taiwanese are generally mutually intelligible.[31] Varieties such as Penang Hokkien and Singaporean Hokkien could be less intelligible to some speakers of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou and Taiwanese varieties due to the existence of loanwords from Malay.

Although the Min Nan varieties of Teochew and Amoy are 84% phonetically similar including the pronunciations of un-used Chinese characters as well as same characters used for different meanings,[citation needed] and 34% lexically similar,[citation needed], Teochew has only 51% intelligibility with the Tong'an Xiamen dialect of the Hokkien language (Cheng 1997)[who?] whereas Mandarin and Amoy Min Nan are 62% phonetically similar[citation needed] and 15% lexically similar.[citation needed] In comparison, German and English are 60% lexically similar.[32]

Hainanese, which is sometimes considered Southern Min, has almost no mutual intelligibility with any form of Hokkien.[31]

Grammar[]

Hokkien is an analytic language; in a sentence, the arrangement of words is important to its meaning.[33] A basic sentence follows the subject–verb–object pattern (i.e. a subject is followed by a verb then by an object), though this order is often violated because Hokkien dialects are topic-prominent. Unlike synthetic languages, seldom do words indicate time, gender and plural by inflection. Instead, these concepts are expressed through adverbs, aspect markers, and grammatical particles, or are deduced from the context. Different particles are added to a sentence to further specify its status or intonation.

A verb itself indicates no grammatical tense. The time can be explicitly shown with time-indicating adverbs. Certain exceptions exist, however, according to the pragmatic interpretation of a verb's meaning. Additionally, an optional aspect particle can be appended to a verb to indicate the state of an action. Appending interrogative or exclamative particles to a sentence turns a statement into a question or shows the attitudes of the speaker.

Hokkien dialects preserve certain grammatical reflexes and patterns reminiscent of the broad stage of Archaic Chinese. This includes the serialization of verb phrases (direct linkage of verbs and verb phrases) and the infrequency of nominalization, both similar to Archaic Chinese grammar.[34]

汝

Lí

You

去

khì

go

買

bué

buy

有

ū

have

錶仔

pió-á

watch

無?

--bô?

no

"Did you go to buy a watch?"

Choice of grammatical function words also varies significantly among the Hokkien dialects. For instance, khit (乞) (denoting the causative, passive or dative) is retained in Jinjiang (also unique to the Jinjiang dialect is thō͘ 度) and in Jieyang, but not in Longxi and Xiamen, whose dialects use hō͘ (互/予) instead.[35]

Pronouns[]

Hokkien dialects differ in the pronunciation of some pronouns (such as the second person pronoun lí or lú or lír), and also differ in how to form plural pronouns (such as -n or -lâng). Personal pronouns found in the Hokkien dialects are listed below:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 我 góa |

阮1gún, góan 咱2 or 俺 lán or án 我儂1,3 góa-lâng |

| 2nd person | 汝 lí, lír, lú |

恁 lín 汝儂3 lí-lâng, lú-lâng |

| 3rd person | 伊 i |