Philippine Hokkien

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Philippine Hokkien or Lannang-Oe (Chinese: 咱人話; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lán-lâng-ōe; lit. 'our people's speech'),[1][2][3] is a particular dialect of Southern Min language spoken by part of the ethnic Chinese population of the Philippines. The use of Hokkien in the Philippines is influenced by Philippine Spanish,[4][5] Tagalog and Philippine English. Hokaglish is an oral contact language involving Philippine Hokkien, Tagalog and English. Hokaglish shows similarities to Taglish (mixed Tagalog and English), the everyday mesolect register of spoken Filipino language within Metro Manila and its environs.

Terminology[]

The term Philippine Hokkien is used when differentiating the variety of Hokkien spoken in the Philippines from those spoken in China, Taiwan and other Southeast Asian countries.[3][2]

Sometimes, it is also colloquially known as Fookien[1] or Fukien[6] around the country.

Sociolinguistics[]

Only 12.2% of all ethnic Chinese in the Philippines have a variety of Chinese as their mother tongue. Nevertheless, the vast majority (77%) still retain the ability to understand and speak Hokkien as a second or third language.[7]

History[]

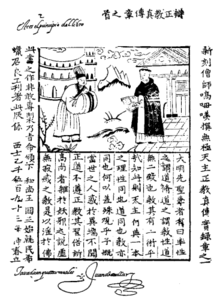

In the early 17th century, Spanish missionaries in the Philippines produced materials documenting the Hokkien varieties spoken by the Chinese trading community who had settled there in the late 16th century:[8][4]

- Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua China (1593), a Hokkien translation of the Doctrina Christiana.[9][5][10][11]

- Dictionario Hispanico Sinicum (1604), a Spanish-Hokkien dictionary, giving equivalent words, but not definitions.[12]

- Bocabulario de la lengua sangleya (c. 1617), a Spanish-Hokkien dictionary, with definitions.

- Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu (1620), a grammar written by a Spanish missionary in the Philippines.[13]

These texts appear to record a Zhangzhou dialect of Hokkien, from the area of Haicheng (an old port that is now part of Longhai).[14]

Education[]

As of 2019, the Ateneo de Manila University, under their Chinese Studies Programme, offers Hokkien 1 (Chn 8) and Hokkien 2 (Chn 9) as electives.[15] Chiang Kai Shek College offers Hokkien classes in their CKS Language Center.[16]

Linguistic features[]

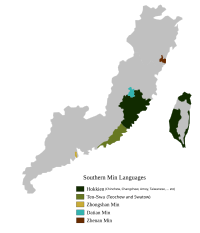

Philippine Hokkien is largely derived from the of Quanzhou but has possibly also absorbed influences from the Amoy dialect of Xiamen and dialects of Quanzhou.[17][18]

Although Philippine Hokkien is generally mutually comprehensible with any Hokkien variant, including Taiwanese Hokkien, the numerous English and Filipino loanwords as well as the extensive use of colloquialisms (even those which are now unused in China) can result in confusion among Hokkien speakers from outside of the Philippines.[citation needed]

Some terms have been shortened into one syllable. Examples include:

- dī-tsa̍p/lī-tsa̍p (二十) > dia̍p/lia̍p (廿 / 廾): twenty; 20 (same format for 20–29, i.e. 二十一[21] is "dia̍p-it" 廿一)[19][irrelevant citation]

- saⁿ-tsa̍p (三十) > sap (卅): thirty; 30 (same format for 30–39, i.e. 三十二[32] is "sa̍p-dī" 卅二)[20][irrelevant citation]

- sì-tsa̍p (四十) > siap (卌): forty; 40 (same format for 40–49, i.e. 四十三[43] is "siap-saⁿ" 卌三)[21][irrelevant citation]

Vocabulary[]

Philippine Hokkien, like other Southeast Asian variants of Hokkien (e.g. Singaporean Hokkien, Penang Hokkien, Johor Hokkien and Medan Hokkien), has borrowed words from other languages spoken locally, specifically Tagalog and English.[1] Examples include:[1]

- manis /ma˧ nis˥˧/: "corn", from Tagalog mais

- lettuce 菜 /le˩ tsu˧ tsʰai˥˩/: "lettuce", from English lettuce + Hokkien 菜 ("vegetable")

- pamkin /pʰam˧ kʰin˥/: "pumpkin", from English pumpkin

Philippine Hokkien also has some vocabulary that is unique to it compared to other varieties of Hokkien:[1]

- 車頭 /tsʰia˧ tʰau˩˧/: "chauffeur"

- 山猴 /suã˧ kau˩˧/: "country bumpkin"

- 義山 /ɡi˩ san˧/: "cemetery" (used in the sign for Manila Chinese Cemetery)

- 霸薯 /pa˥˥˦ tsi˨˦/: "potato"

- 麵頭 /bin˩ tʰau˨˦/: "bread"

- 病厝 /pĩ˩ tsʰu˦˩/: "hospital"

See also[]

- Hoklo people

- Hokkien culture

- Hokkien architecture

- Written Hokkien

- Hokkien media

- Taiwanese Hokkien

- Singapore Hokkien

- Penang Hokkien

- Southern Malaysia Hokkien

- Medan Hokkien

- Mandarin Chinese in the Philippines

- Pe̍h-ōe-jī

- Taiwanese Romanization System

- Holopedia

- Speak Hokkien Campaign

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Tsai, Hui-Ming 蔡惠名 (2017). Fēilǜbīn zán rén huà (Lán-lâng-uē) yánjiū 菲律賓咱人話(Lán-lâng-uē)研究 [A Study of Philippine Hokkien Language] (PhD thesis) (in Chinese). National Taiwan Normal University.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lin, Philip T. (2015). Taiwanese Grammar: A Concise Reference. Greenhorn Media. ISBN 978-0-9963982-1-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel Wong (2016). Exploring Trilingual Code-Switching: The Case of 'Hokaglish' (PDF). The 26th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, Manila, Philippines.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Klöter (2011)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Van der Loon (1966)

- ^ Chan Yap, Gloria (1980). Hokkien Chinese Borrowings in Tagalog. Canberra: Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 9780858832251.

- ^ See, Teresita Ang (1997). The Chinese in the Philippines: Problems and Perspectives. Manila: Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran. p. 57.

- ^ Chappell, Hilary; Peyraube, Alain (2006). "The Analytic Causatives of Early Modern Southern Min in Diachronic Perspective". In Ho, D.-a.; Cheung, S.; Pan, W.; Wu, F. (eds.). Linguistic Studies in Chinese and Neighboring Languages. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. pp. 973–1011.

- ^ Yue, Anne O. (1999). "The Min Translation of the Doctrina Christiana". Contemporary Studies on the Min Dialects. Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series 14. Chinese University Press. pp. 42–76. JSTOR 23833463.

- ^ Cobo, Juan (1593). Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua China, compuesta por los padres ministros de los Sangleyes, de la Orden de Sancto Domingo (in Spanish). Manila – via UST Miguel de Benavidez Library.

- ^ Cobo, Juan (1593). Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua China, compuesta por los padres ministros de los Sangleyes, de la Orden de Sancto Domingo (in Spanish). Manila – via ip194097.ntcu.edu.tw.

- ^ Zulueta, Lito B. (February 8, 2021). "World's Oldest and Largest Spanish-Chinese Dictionary Found in UST". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Mançano, Melchior; Feyjoó, Raymundo (1620). Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu – via Universitat de Barcelona.

- ^ Van der Loon (1967)

- ^ "Minor in Chinese Studies". Ateneo de Manila University. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "CKS Language Center". Chiang Kai Shek College. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Cai, Huiming 蔡惠名; Wang, Guilan 王桂蘭 (2011). "Fēilǜbīn fújiàn huà chūbù diàochá chéngguǒ" 菲律賓福建話初步調查成果 [Preliminary Research Results on Philippine Hokkien]. Hǎi wēng tái yǔwén xué jiàoxué jìkān 海翁台語文學教學季刊 (in Chinese) (11): 52. doi:10.6489/HWTYWHCHCK.201103.0046.

- ^ Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel Ong Wong (2018). Philippine Hybrid Hokkien as a Postcolonial Mixed Language: Evidence from Nominal Derivational Affixation Mixing (M.A. thesis). National University of Singapore.

- ^ 廿 jia̍p/lia̍p. Táiwān mǐnnán yǔ chángyòng cí cídiǎn 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, R.O.C.

- ^ "Entry a00433". Jiàoyù bù yìtǐzì zìdiǎn 教育部異體字字典 (in Chinese).

- ^ 卌 siap. Táiwān mǐnnán yǔ chángyòng cí cídiǎn 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, R.O.C.

Further reading[]

- Klöter, Henning (2011). The Language of the Sangleys: A Chinese Vernacular in Missionary Sources of the Seventeenth Century. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18493-0. - An analysis and facsimile of the Arte de la Lengua Chio-chiu (1620), the oldest extant grammar of Hokkien.

- Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china (in Spanish). Manila. 1607 – via Biblioteca Digital Hispánica. – Hokkien translation of the Doctrina Christiana.

- Arte de la Lengua Chio-chiu (in Spanish). Manila. 1620 – via Biblioteca Patrimonial Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona. – A manual for learning Hokkien written by a Spanish missionary in the Philippines.

- Van der Loon, Piet (1966). "The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies, Part 1" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 12: 1–43.

- Van der Loon, Piet (1967). "The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies, Part 2" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 13: 95–186.

- Chinese-Filipino culture

- Languages of the Philippines

- Hokkien-language dialects