Immigration to Germany

| German citizenship and immigration |

|---|

| Immigration |

|

| Citizenship |

| Agencies |

| History |

|

| Immigration to Germany, 1991-2020 | |

| Source: Federal Statistical Office of Germany[1] | |

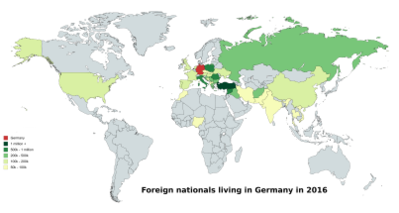

Immigration to Germany refers to the movement of non-German citizens to Germany. Since 1990, Germany has consistently ranked as one of the five most popular destination countries for immigrants in the world.[2] As of 2019, around 13.7 million people living in Germany, or about 17% of the population, are first-generation immigrants.[3] The majority of immigrants in Germany are from Eastern Europe, Southern Europe and the Middle East.

Immigration to modern Germany has generally risen and fallen with the country's economy.[4] The economic boom of the 2010s, coupled with the elimination of working visa requirements for many EU citizens, brought a sustained inflow from elsewhere in Europe.[5] Separate from economic trends, the country has also seen several distinct major waves of immigration. These include the resettlement of ethnic Germans from eastern Europe after World War II, the guest worker program of the 1950s–1970s, and ethnic Germans from former communist states claiming their right of return after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[6] Germany also accepted significant numbers of refugees from the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s and the Syrian civil war.

Motivated in part by low birth rates and labor shortages, German government policy towards immigration has generally been relatively liberal since the 1950s,[7] although citizenship laws remained relatively restrictive until the mid-2000s. On 1 January 2005, a new immigration law came into effect. The political background to this new law was that Germany, for the first time ever, was acknowledged to be a destination for immigrants. The practical changes[clarification needed] to immigration procedures were relatively minor. New immigration categories, such as "highly skilled professional" and "scientist" were introduced to attract valuable professionals to the German labour market. The development within German immigration law shows that immigration of skilled employees and academics has eased[clarification needed] while the labour market remains closed for unskilled workers.

According to the federal statistics office in 2016, over one out of five Germans has at least partial roots outside of the country.[8]

In March 2020, Germany enacted new rules under the 2019 Skilled Immigration Act (de:Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetz).[9] The new rules expand the availability of German work visas to qualified skilled immigrants from outside the EU.

History of immigration to Germany[]

After World War II until reunification (1945-1980)[]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2015) |

Towards the end of World War II, and in its aftermath, up to 12 million refugees of ethnic Germans, so-called "Heimatvertriebene" (German for "expellees", literally "homeland displaced persons") were forced to migrate from the former German areas, as for instance Silesia or East Prussia, to the new formed States of post-war Germany and Allied-occupied Austria, because of changing borderlines in Europe.[10][11] A big wave of immigration to Germany started in the 1960s. Due to a shortage of laborers during the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") in the 1950s and 1960s, the West German government signed bilateral recruitment agreements with Italy in 1955, Greece in 1960, Turkey in 1961, Morocco in 1963, Portugal in 1964, Tunisia in 1965 and Yugoslavia in 1968. These agreements allowed the recruitment of so-called Gastarbeiter ("guest workers") to work in the industrial sector in jobs that required few qualifications. Children born to 'Gastarbeiter' received the right to reside in Germany but were not granted citizenship; this was known as the Aufenthaltsberechtigung ("right of residence"). Many of the descendants of those Gastarbeiter still live in Germany and many have acquired German citizenship, though some have moved back to their countries of origin.

The German Democratic Republic (GDR) recruited workers from outside its borders differently. It criticized the Gastarbeiter policy, calling it capitalist exploitation of poor foreigners, and preferred to see its foreign workers as socialist "friends" who traveled to the GDR from other communist or socialist countries in order to learn skills which could then be applied in their home countries. Most of these came from North Vietnam, North Korea, Angola, Mozambique and Cuba. Following German reunification in 1990 many foreign workers in the new federal states of the former GDR had no legal status as immigrant workers under the Western system. Consequently, many faced deportation or premature termination of residence and work permits, as well as open discrimination in the workplace.

1980-1993[]

During the 1980s, a small but steady stream of East Germans immigrating to the West (Übersiedler) had begun with the gradual opening of the Eastern bloc. It swelled to 389,000 in 1990. After the immigration law change in 1993, it decreased by more than half to 172,000.[12]

During the same time, the number of ethnic Germans (Aussiedler) -Germans who had settled in German territory sometimes for centuries until WWII, i.e. in present-day Eastern Europe and Russia- began to rise in the mid-1980s to about 40,000 each year. In 1987, the number doubled, in 1988 it doubled again and in 1990 nearly 400,000 immigrated. Upon arrival, ethnic Germans became citizens at once according to Article 116 of the Basic Law, and received financial and many social benefits, including language training, as many did not speak German. Social integration was often difficult, even though ethnic Germans were entitled to German citizenship, but to many Germans they did not seem German. In 1991, restrictions went into effect, in that ethnic Germans were assigned to certain areas, losing benefits if they were moving. The German government also encouraged the estimated several million ethnic Germans living in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to remain there. Since January 1993, no more than 220,000 ethnic Germans may immigrate per year.[12] In total, more than 4.5 million ethnic Germans moved to Germany between 1990 and 2007.[13]

And in parallel a third stream of immigration starting in the mid 1980s were war refugees, of which West Germany accepted more than any other West European country due to an unqualified right to asylum. From 1986 to 1989, about 380,000 refugees sought asylum, mostly from Iran and Lebanon. Between 1990 and 1992 nearly 900,000 people from former Yugoslavia, Romania, or Turkey sought asylum in a united Germany.[12] In 1992, 438,000 applied, and Germany admitted almost 70 percent of all asylum seekers registered in the European Community.[14] By comparison, in 1992 only about 100,000 people sought asylum in the U.S.[15] The growing numbers of asylum seekers led to a constitutional change severely restricting the previously unqualified right of asylum, that former "refugees [had] held sacred because of their reliance on it to escape the Nazi regime".[14]:159 In December 1992, the Bundestag passed legislation amending the Basic Law, in which article 16 was changed to 16a.[14] Persons entering Germany save from third countries were no longer granted asylum, and applications from nationals of so-called safe third countries of origin were refused.[16] As of 2008, the numbers of asylum seekers had dropped significantly.[17]:16

1993-2014[]

Due to the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars, a rising number of refugees headed to Germany and other European countries.[18] Though only about 5 percent of the asylum applications were approved and appeals sometimes took years to be processed, many asylum seekers were able to stay in Germany and received financial and social aid from the government.[12][19]As of 2013, the approval rate was about 30 percent, and 127,000 people sought asylum.[20] During 2014 a total of about 202,834 people sought asylum in Germany.[21] Even more asylum seekers will be expected for 2015 with more than 800,000 people.[22]

As of 2014, about 16.3 million people with an immigrant background were living in Germany, accounting for every fifth person[20] Of those 16.3 million, 8.2 million had no German citizenship, more than ever before. Most of them had Turkish, Eastern European or Southern European background. The majority of new foreigners coming to Germany in 2014 were from new EU member states such as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia, non-EU European countries like Albania, North Macedonia, Switzerland and Norway or from the Middle East, Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, North America, Australia and Zealandia. Due to ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, many people are hoping to seek asylum in the European Union and Germany.[24] The vast majority of immigrants are residing in the so-called old states of Germany.[25][26]

2015 Migration crisis[]

| Illegal immigrants in Germany 2008 onwards | |

| Source: Eurostat third country nationals present in Germany.[27] | |

In June 2015, new arrivals of asylum seekers, which had been increasing steadily for years,[28] began to rise sharply,[29] driven especially by refugees fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. An original projection of 450,000 asylum seekers entering Germany for the whole of 2015 was revised upwards to 800,000[22] in August and again in September to over 1 million.[30] The actual final number was 1.1 million.[31]

Most of the refugees entering Europe around this time came by land via the so-called "Balkan route." According to an EU law (the Dublin regulation), refugees were required to file asylum claims in the first EU country they set foot in, which for many was Hungary, and remain there while the claim is processed. As a result, Hungary registered 150,000 asylum seekers by August 2015. However, the vast majority of these refugees had no desire to remain in Hungary and wanted to move on to Western or Northern Europe, leading to a sizable population of refugees "trapped" in the country.[32] The Hungarian government began to house refugees in camps under squalid conditions.[33] The German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, overwhelmed with the task of processing the sheer number of incoming asylum claims, was unable to prioritize deporting refugees to Hungary and decided to suspend enforcement of the Dublin regulation for Syrian nationals. As a result, refugees in Hungary requested to be allowed leave for Germany; several thousand began making their way across Hungary and Austria towards Germany on foot. Claiming it was no longer able to process asylum claims properly, Hungary began providing buses for refugees to the Austrian border. Responding to a wave of public sympathy in reaction to widely broadcast scenes of police brutality and refugees dying at the hands of smugglers in Hungary, and unable to keep the migrants out of the country without resorting to brutal force, the German and Austrian chancellors, Angela Merkel and Werner Faymann decided to allow the refugees in. The publicity from this decision led hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the Syrian civil war to make for Germany.[32]

In 2015, Germany received 900 000 asylum seekers and spent €16 billion (0.5% of GDP) on its migrants that year.[34]

Although the number of refugees in formal employment more than tripled between 2016 to 2019,[35] as a group they remain overrepresented in unemployment statistics, which experts ascribe to a combination of red tape and refugees' difficulty in finding housing.[36] Employment among Syrians and Afghans, the most two common nationalities among the 2015-2016 refugee arrivals, rose by 79% and 40%, respectively, between 2017 to 2018.[37]

The 2018 Ellwangen police raid, in which residents of a migrant shelter rioted to prevent police from deporting an asylum seeker whose claim had been deemed invalid, sparked a significant political debate.[38]

In 2015, most Germans were very supportive of the mass immigrations occurring due to conflicts in the ME and Northern Africa. Chancellor Angela Merkel, coined the phrase which most of the country rallied behind, “Wir schaffen das,” which translates into English as, we can do it. In 2015, the brunt of the European immigration crisis was placed on Germany when 890,000 refugees crossed the border and applied for asylum, most of them fleeing from the Syrian War. By 2018, 670,000 out of 700,000 Syrians living in Germany immigrated as a result of internal strife and conflict in Syrian beginning in 2011.[39] With such an influx of migrants, Germany seeks to accommodate those displaced by war. This is due to a lack of a relationship with the government in Syria, as its nearly impossible to deport refugees back to Syria without government contact nor ongoing flights between the two countries.[40] As of A 2015 survey shows that 46% of the entire German population was facilitating help in some way for refugees. All over, German citizens were creating initiatives and support groups for asylum seekers as well as donating their time to help on site with refugees. Media helped shape the German attitudes as well as put pressure on the government by covering the victims of immigration and by showing individual stories, which humanized them. After the events in Cologne on New Year's Eve, there was a drastic change of media coverage, as well as the public opinion of immigrants. The media went from showing women and children who suffered from war crime victims, to Arab men assaulting German women in large groups. The media also highlighted massive groups of immigrants crossing the border into Germany instead of the earlier coverage of individual refugee's stories. This caused Germans to now fear how expensive all of these immigrants would be, the earlier phrase, “Wir schaffen das” suggested that funding for these refugees was not an issue. The cost to support all of these refugees added up to around 21 billion euros, about the size of Germany's defense budget.

Governmental opinion has also shifted over the years. The intake of refugees has consistently dropped over the last few years; however, the number of deportations only continued to increase and leveled out at around 20,000.[41]

The influx of migrant refugees has had a negative impact on the crime rates of Germany, mirroring the phenomenon that occurred during the mass immigration of ethnic Germans from areas of the Soviet Union after its collapse.[42] Since the 1990s, after the rise in crime precipitated by the influx of ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union and refugees from the former Yugoslavia, the crime rate dropped steadily in Germany until 2014. However, the rate of crime has been increasing over the last few years. From 2014 to 2016, the amount of crime has increased. Violent crimes saw an increase of 7.2% over that period of time.[43] A government backed study of the Lower Saxony Region showed an increase of 10.2% in violent crimes. This region is also one of the regions to take in the most asylum seekers.[44] Asylum seekers are four times as represented in the number of suspects in police investigations compared to the percentage of the total population of Germany.[45]

Immigration regulations[]

EU citizens[]

European Union free movement of workers principles require that all EU member state citizens have the right to solicit and obtain work in Germany regardless of citizenship. These basic rules for freedom of movement are given in Article 39 of the Treaty on European Union.

Immigration options for non-EU citizens[]

Immigration to Germany as a non-EU-citizen is limited to skilled or highly educated workers and their immediate family members.[46] In April 2012, European Blue Card legislation was implemented in Germany, allowing highly skilled non-EU citizens easier access to work and live in Germany. Although uptake of the scheme has grown steadily since then, its use remains modest; around 27,000 blue cards were issued in Germany in 2018.[47]

Self-employment requires either an initial investment of EUR 250,000 and the creation of a minimum 5 jobs.[48]

2019 Skilled Immigration Act[]

New regulations were enacted in 2020 in response to the 2019 Skilled Immigration Act.[9] In order to qualify for a visa under the new rules, applicants must obtain an official recognition of their professional qualification from a certification authority recognized by the German government.[9] Further, the applicant must meet language competency requirements and obtain a declaration from their prospective employer.[9]

Student visa[]

According to a study of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), around 54 percent of foreign students in Germany decide to stay after graduation.[49]

Asylum seekers and refugees[]

German asylum law is based on the 1993 amendment of article 16a of the Basic Law as well as on the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.

In accordance with the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Germany grants refugee status to persons that are facing prosecution because of their race, religion, nationality or belonging to a special group. Since 2005, recognized refugees enjoy the same rights as people who were granted asylum.[50] Germany's national ban on deportation doesn't permit returning refugees to their home country should doing so place them in imminent danger or that doing so would break EU human rights laws. This policy is a major catalyst to the large influx of Syrian refugees following the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War.[51]

The distribution of refugees among the federal states is calculated using the "Königsteiner Schlüssel", which is recalculated annually.[52]

Germany hosts one of the largest populations of Turkish people outside Turkey. Kurds make up 80 to 90 percent of all Turkish refugees in Germany while the rest of the refugees are former Turkish military officers, teachers, and other types of public servants who fled the authoritarian government following the coup attempt in July 2016.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59] Among Iraqi refugees in Germany, about 50 percent are Kurds.[60] There are approximately 1.2 million Kurds in Germany.[61]

An institute of forensic medicine in Münster determined the age of 594 of unaccompanied minors in 2019 and found that 234 (40%) were likely 18 years or older and would therefore be processed as adults by authorities. The sample was predominantly males from Afghanistan, Guinea, Algeria and Eritrea.[62]

In 2015, responding to relatively high numbers of unsuccessful asylum applications from several Balkan countries (Serbia, Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro), the German government formally declared these countries "generally safe" to speed up their processing.[63]

Naturalization[]

A person who has immigrated to Germany may choose to become a German citizen. The standard pathway to citizenship is known as Anspruchseinbürgerung (roughly, naturalization by entitlement). In this process, when the applicant fulfills certain criteria they are entitled to become German citizens; the decision is not generally subject to the judgment of a government official. The applicant must:[64]:19

- be a permanent resident of Germany

- have lived in Germany legally for at least eight years (seven years if they have passed an Integrationskurs)

- not live on welfare as the main source of income unless unable to work (for example, if the applicant is a single mother)

- be able to speak German at a 'B1' level in the CEFR standard

- pass a citizenship test. The examination tests a person's knowledge of the German constitution, the Rule of Law and the basic democratic concepts behind modern German society. It also includes a section on the constitution of the Federal State in which the applicant resides. The citizenship test is obligatory unless the applicant can claim an exemption such as illness, a disability, or old age.

- not have been convicted of a serious criminal offence

- be prepared to swear an oath of loyalty to democracy and the German constitution

- be prepared to renounce all former citizenships, unless the applicant obtains an exemption. The principal exemptions are:

- the applicant is a citizen of another European Union country, or of Switzerland;

- the applicant is a refugee, holding a 1951 convention travel document;

- the applicant is from a country where experience shows that it is impossible or extremely difficult to be released from nationality (such as Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Lebanon, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia);

- renunciation of their former citizenship would cause the applicant serious economic harm. A typical examples is if the person would be unable to inherit property in the country of origin.

A person who does not fulfill all of these criteria may still apply for German citizenship by discretionary naturalisation (Ermessenseinbürgerung) as long as certain minimum requirements are met.[64]:38

Spouses and same-sex civil partners of German citizens can be naturalised after only 3 years of residence (and two years of marriage).[64]:42

Under certain conditions children born on German soil after the year 1990 are automatically granted German citizenship and, in most cases, also hold the citizenship of their parents' home country.

Applications for naturalisation made outside Germany are possible under certain circumstances, but are relatively rare.

Immigrant population in Germany by country of birth[]

According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany in 2012, 92% of residents (73.9 million) in Germany had German citizenship,[65] with 80% of the population being Germans (64.7 million) having no immigrant background. Of the 20% (16.3 million) people with immigrant background, 3.0 million (3.7%) had Turkish, 1.5 million (1.9%) Polish, 1.2 million (1.5%) Russian and 0.85 million (0.9%) Italian background.[66]

In 2014, most people without German citizenship were Turkish (1.52 million), followed by Polish (0.67 million), Italian (0.57 million), Romanians (0.36 million) and Greek citizens (0.32 million).[67]

As of 2020, the most common groups of resident foreign nationals in Germany were as follows:[68]

| Rank | Nationality | Population | % of foreign nationals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 11,432,460 | 100 | |

| 1 | 1,461,910 | 12.8 | |

| 2 | 866,690 | 7.6 | |

| 3 | 818,460 | 7.2 | |

| 4 | 799,180 | 7.0 | |

| 5 | 648,360 | 5.7 | |

| 6 | 426,845 | 3.7 | |

| 7 | 388,700 | 3.4 | |

| 8 | 364,285 | 3.2 | |

| 9 | 271,805 | 2.4 | |

| 10 | 264,565 | 2.3 | |

| 11 | 263,300 | 2.3 | |

| 12 | 259,500 | 2.3 | |

| 13 | 242,855 | 2.1 | |

| 14 | 211,460 | 1.8 | |

| 15 | 211,335 | 1.8 | |

| 16 | 186,910 | 1.6 | |

| 17 | 181,645 | 1.6 | |

| 18 | 150,840 | 1.3 | |

| 19 | 150,530 | 1.3 | |

| 20 | 145,610 | 1.3 | |

| 21 | 145,510 | 1.3 | |

| 22 | 140,590 | 1.2 | |

| 23 | 138,555 | 1.2 | |

| 24 | 123,400 | 1.1 | |

| 25 | 121,115 | 1.1 | |

| 26 | 117,450 | 1.0 | |

| 27 | 103,620 | 0.9 | |

| 28 | 91,375 | 0.8 | |

| 29 | 79,725 | 0.7 | |

| 30 | 75,735 | 0.7 | |

| 31 | 75,495 | 0.7 | |

| 32 | 75,355 | 0.7 | |

| 33 | 73,905 | 0.6 | |

| 34 | 61,965 | 0.5 | |

| 35 | 59,900 | 0.5 | |

| 36 | 59,070 | 0.5 | |

| 37 | 58,730 | 0.5 | |

| 38 | 49,500 | 0.4 | |

| 39 | 47,495 | 0.4 | |

| 40 | 46,980 | 0.4 | |

| 41 | 41,195 | 0.4 | |

| 42 | 41,090 | 0.4 | |

| 43 | 40,480 | 0.4 | |

| 44 | 39,270 | 0.3 | |

| 45 | 38,405 | 0.3 | |

| 46 | 37,430 | 0.3 | |

| 47 | 36,325 | 0.3 | |

| 48 | 35,565 | 0.3 | |

| 49 | 29,610 | 0.3 | |

| 50 | 28,985 | 0.3 | |

| Other nationalities | 1,003,850 | 8.8 |

Comparison with other European Union countries[]

According to Eurostat, 47.3 million people living in the European Union in 2010 were born outside their resident country which corresponds to 9.4% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (6.3%) were born outside the EU and 16.0 million (3.2%) were born in another EU member state. The largest absolute numbers of people born outside the EU were in Germany (6.4 million), France (5.1 million), the United Kingdom (4.7 million), Spain (4.1 million), Italy (3.2 million), and the Netherlands (1.4 million).[69]

| Country | Total population (thousands)[citation needed] |

Total foreign-born (thousands)[citation needed] |

% | Born in other EU state (thousands)[citation needed] |

% | Born in a non-EU state (thousands)[citation needed] |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU 27 | 501,098 | 47,348 | 9.4 | 15,980 | 3.2 | 31,368 | 6.3 |

| Germany | 81,802 | 9,812 | 12.0 | 3,396 | 4.2 | 6,415 | 7.8 |

| France | 64,716 | 7,196 | 11.1 | 2,118 | 3.3 | 5,078 | 7.8 |

| United Kingdom | 62,008 | 7,012 | 11.3 | 2,245 | 3.6 | 4,768 | 7.7 |

| Spain | 45,989 | 6,422 | 14.0 | 2,328 | 5.1 | 4,094 | 8.9 |

| Italy | 60,340 | 4,798 | 8.0 | 1,592 | 2.6 | 3,205 | 5.3 |

| Netherlands | 16,575 | 1,832 | 11.1 | 428 | 2.6 | 1,404 | 8.5 |

| Greece | 11,305 | 1,256 | 11.1 | 315 | 2.8 | 940 | 8.3 |

| Sweden | 9,340 | 1,337 | 14.3 | 477 | 5.1 | 859 | 9.2 |

| Austria | 8,367 | 1,276 | 15.2 | 512 | 6.1 | 764 | 9.1 |

| Belgium (2007) | 10,666 | 1,380 | 12.9 | 695 | 6.5 | 685 | 6.4 |

| Portugal | 10,637 | 793 | 7.5 | 191 | 1.8 | 602 | 5.7 |

| Denmark | 5,534 | 500 | 9.0 | 152 | 2.8 | 348 | 6.3 |

Crime[]

Only a very small percentage, around 4%, of immigrants in Germany are accused of committing crimes.[71] Non-German citizens are, in general, over-represented among suspects in criminal investigations (see horizontal bar chart).[70] However, the complex nature of the data means it is not straightforward to make observations about the crime rates among immigrants. One factor is that crimes committed by foreign nationals are twice as likely to be reported as those committed by German citizens.[72] In addition, the clearance rate (the percentage of crimes that are solved successfully) is extremely low in some categories, such as pickpocketing (5% solved) and burglaries (17% solved). When considering solved crimes only, non-German nationals make up around 8% of all suspects.[73] A disproportionate number of organized crime families in Germany are run by immigrants or their children. One-fifth of investigations into organized crime involve one or more non-German suspect.[73] This has been attributed to the lack of effort made to integrate newly arrived immigrants in the 1960s and 1970s, who at the time were seen as "temporary" guest workers.[74]

References[]

- ^ "International Migration Database". destatis.de. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Germany Top Migration Land After U.S. in New OECD Ranking". Migration Policy Institute. 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund I | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Right and wrong ways to spread languages around the globe". The Economist. 31 March 2018. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Fünf Jahre Arbeitnehmerfreizügigkeit in Deutschland | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Jones, P.N.; Wild, M.T. (February 1992). "Western Germany's 'third wave' of migrants: the arrival of the Aussiedler". Geoforum. 23 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/0016-7185(92)90032-Y. PMID 12285947.

- ^ "Germany Population 2018", World Population Review

- ^ "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund um 8,5 % gestiegen".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Skilled Immigration Act (Fachkräfte-Einwanderungsgesetz)". German Missions in India. 6 March 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ [1], SpiegelOnline 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Konrad Adenauer Stiftung" , viewed on 31 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Eric Solsten (1995). "Germany: A Country Study; Chapter: Immigration". Washington DC: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Phalnikar, Sonia (7 September 2007). "Russia Hopes to Lure Back Ethnic Germans | DW | 07.09.2007". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kay Hailbronner (1994). "Asylum law reform in the German Constitution" (PDF). American University International Law Review. pp. 159–179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ James M. Didden (1994). "Toward collective responsibility in asylum law: Reviving the eroding right to political asylum in the US and the Federal Republic of Germany" (PDF). American University International Law Review. pp. 79–123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF): Asylum law

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF): Annual Report on Migration and International Protection Statistics 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ " Kriegsflüchtlinge aus dem ehemaligen Jugoslawien nach Zielland (Schätzung des UNHCR, Stand März 1995)", viewed on 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Asylbewerberleistungen", published on 4 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pegida - Faktencheck: Asylbewerber". Frankfurter Rundschau. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "202.834 Asylanträge im Jahr 2014", Bundesministerium des Inneren; press release 14 January 2015 .

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Zahl der Flüchtlinge erreicht "Allzeithoch"" Retrieved 19 August 2015

- ^ "Mehr als 10 Millionen Ausländer in Deutschland".

- ^ Knapp 8,2 Millionen Ausländer leben in Deutschland, "sueddeutsche.de" published in March 2015 .

- ^ "Ausländische Bevölkerung nach Ländern".

- ^ "Conflicts in the Middle East fueled by religious intolerance", Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Eurostat table [migr_eipre] Third country nationals found to be illegally present - annual data (rounded)". Eurostat. 17 July 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Integration, Mediendienst. "Zahl der Flüchtlinge | Flucht & Asyl | Zahlen und Fakten | MDI". Mediendienst Integration (in German). Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Hanewinkel, Vera. "Fluchtmigration nach Deutschland und Europa: Einige Hintergründe". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Neue Prognose für Deutschland 2015: Vizekanzler Gabriel spricht von einer Million Flüchtlingen", Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Schönhagen, Ulrich Herbert , Jakob. "Vor dem 5. September. Die "Flüchtlingskrise" 2015 im historischen Kontext | APuZ". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schönhagen, Ulrich Herbert , Jakob. "Vor dem 5. September. Die "Flüchtlingskrise" 2015 im historischen Kontext | APuZ". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: People treated 'like animals' in Hungary camp". BBC News. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Who bears the cost of integrating refugees?" (PDF). OECD Migration Policy Debates. 13 January 2017: 2.

- ^ Becher, Lena (9 July 2019). "Die Beschäftigung von Flüchtlingen wächst – die Arbeitslosigkeit auch". O-Ton Arbeitsmarkt. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Dernbach, Andrea (23 January 2020). "Wie das Integrationsgesetz die Integration behindert". www.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Graf, Johannes. "Migration Monitoring: Educational and Labour Migration to Germany" (PDF). bamf.de. Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. p. 39.

- ^ Clashes at migrant hostel stir German integration fears Reuters, 3 May 2018

- ^ Hindy, Lily (6 September 2018). "Germany's Syrian Refugee Integration Experiment". tcf.org. The Century Foundation. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Sanderson, Sertan (11 December 2020). "German ban on deportation to Syria to expire within weeks". www.infomigrants.com. Info Migrants. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ "Current Figures on Asylum". Archived from the original on 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Immigration, Regional Conditions and Crime: Evidence from an Allocation Policy in Germany" (PDF).

- ^ "German Crime Statistics".

- ^ "Germany: Migrants 'may have fuelled violent crime rise'". BBC News. 3 January 2018.

- ^ "German Police Crime Statistics".

- ^ "Ordinance on employment (German)". Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "Figures on the EU Blue Card". BAMF - Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Residence Act in the version promulgated on 25 February 2008 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 162), last amended by Article 3 of the Act of 6 September 2013 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 3556)

- ^ "BAMF's Graduates Study: Every second foreign student stays in Germany after graduation". Make it in Germany. German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF): Protecting refugees

- ^ "National ban on deportation". www.bamf.de. BAMF. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ "Gemeinsame Wissenschaftskonferenz – Büro – Bekanntmachung des Königsteiner Schlüssels für das Jahr 2014". 4 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Auffallend viele kurdische Flüchtlinge".

- ^ "BMI Bundesinnenminister Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble: Asylbewerberzugang im Jahr 2005 auf niedrigsten Stand seit 20 Jahren". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ "Asylanträge von Türken in BW: "Fast 90 Prozent sind Kurden" - Baden-Württemberg - Nachrichten".

- ^ Politik (25 December 2016). "Zahl der türkischen Asylbewerber verdreifacht". Spiegel.de.

- ^ "Nach Putschversuch: Immer mehr Türken beantragen Asyl in Deutschland". Welt.de. 25 December 2016.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters. "Turkish asylum applications in Germany jump 55 percent this year". U.S. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "Report: At least 1,400 Turkish nationals claimed asylum in Germany in Jan-Feb alone - Turkey Purge". Turkey Purge. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ http://www.rudaw.net/english/world/251120152

- ^ Online, FOCUS. "Zweifel an Minderjährigkeit: 40 Prozent der überprüften Flüchtlinge gaben Alter falsch an". FOCUS Online (in German). Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Berlin plant Sammelunterkunft für Balkan-Flüchtlinge". Zeit.de (in German). 28 December 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Federal Government Commissioner for Migrants, Refugees and Integration. Wege zur Einbürgerung. Wie werde ich Deutsche? – Wie werde ich Deutscher? Archived 11 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine 2008.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis). Population based on the 2011 Census. Population by sex and citizenship Archived 28 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). Migrationsbericht des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge im Auftrag der Bundesregierung. Migrationsbericht 2012 Archived 25 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 2014.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis). Foreign population, 2007 to 2013 by selected citizenships.

- ^ https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/auslaend-bevoelkerung-2010200207004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

- ^ 6.5% of the EU population are foreigners and 9.4% are born abroad, Eurostat, Katya VASILEVA, 34/2011. Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pancevski, Bojan (15 October 2018). "An Ice-Cream Truck Slaying, Party Drugs and Real-Estate Kings: Ethnic Clans Clash in Berlin's Underworld". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Walburg, Christian. "Migration und Kriminalität – Erfahrungen und neuere Entwicklungen | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Knight, Ben (3 January 2018). "Study: Only better integration will reduce migrant crime rate". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kriminalität im Kontext von Zuwanderung: Bundeslagebild 2019. Bundeskriminalamt. 2019. pp. 54, 60.

- ^ Ghadban, Ralph (28 September 2018). "Die Macht der Clans". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Immigration in Germany. |

Governmental[]

- "6.180,013" Ausländer in Deutschland

- "Unsere Aufnahmekapazität ist begrenzt, ..."

- German Foreign Office

- Federal Office for Migration and Refugees

Non-governmental[]

- Immigration to Germany

- Foreign relations of Germany