Kumārajīva

Kumārajīva | |

|---|---|

| Born | 344 CE Kucha Kingdom (now Kuqa, China) |

| Died | 413 CE |

| Occupation | Buddhist monk, scholar, translator, and philosopher |

| Known for | Translation of Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit to Chinese, founder of the Sanlun school of Mahayana Buddhism |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism 汉传佛教 / 漢傳佛教 |

|---|

|

| Kumārajīva | |||

|---|---|---|---|

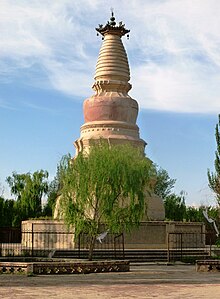

The Statue of Kumārajīva in front of the Kizil Caves in Kuqa County, Xinjiang, China | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 鳩摩羅什 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 鸠摩罗什 | ||

| |||

| Sanskrit name | |||

| Sanskrit | कुमारजीव | ||

Kumārajīva (Sanskrit: कुमारजीव, simplified Chinese: 鸠摩罗什; traditional Chinese: 鳩摩羅什; pinyin: Jiūmóluóshí; Wade–Giles: Chiu1 mo2 lo2 shih2, 344–413 CE)[1] was a Buddhist monk, scholar, missionary and translator from the Kingdom of Kucha. He first studied teachings of the Sarvastivadin schools, later studied under Buddhasvāmin, and finally became an adherent of Mahayana Buddhism, studying the Mādhyamaka doctrine of Nāgārjuna.

Kumārajīva settled in Chang'an during the Sixteen Kingdoms era. He is mostly remembered for the prolific translation of Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit to Chinese he carried out during his later life.

Kumārajīva is the founder of the Sanlun school of Mahayana Buddhism, which is also known as the "Three Treatise school" and whose Japanese equivalent is the Sanron school. See East Asian Mādhyamaka.

Life[]

Family and background[]

Kumārajīva's father Kumārāyana was from ancient India, probably from present-day Kashmir,[2][3][4] and his mother was a Kuchan princess who significantly influenced his early studies. His grandfather is supposed to have had a great reputation. His father became a monk, left Kashmir, crossed the Pamir Mountains and arrived in Kucha, where he became the royal priest. The sister of the king, Jīva, also known as Jīvaka, married him and they produced Kumārajīva. Jīvaka joined the Tsio-li nunnery, north of Kucha, when Kumārajīva was just seven.

Childhood and education[]

When his mother Jīvaka joined the Tsio-li nunnery, Kumārajīva was just seven but is said to have already committed many texts and sutras to memory. He proceeded to learn Abhidharma, and after two years, at the age of nine, he was taken to Kashmir by his mother to be better educated under . There he studied Dīrgha Āgama, Madhyama Āgama and the , before returning with his mother three years later. On his return via Tokharestan and Kashgar, an arhat predicted that he had a bright future and would introduce many people to Buddhism. Kumārajīva stayed in Kashgar for a year, ordaining the two princely sons of (himself the son of the king of Yarkand) and studying the Abhidharma Piṭaka of the Sarvastivada under the Kashmirian , as well as the four Vedas, five sciences, Brahmanical sacred texts, astronomy. He studied mainly Āgama and Sarvastivada doctrines at this time.

Kumārajīva left Kashgar with his mother Jīvaka at age 12, and traveled to Turpan, the north-eastern limit of the kingdom of Kucha, which was home to more than 10,000 monks. Somewhere around this time, he encountered the master , who instructed him in early Mahayana texts. Kumārajīva soon converted, and began studying Madhyamaka texts such as the works of Nagarjuna.

Early fame in Kucha[]

In Turpan his fame spread after beating a Tirthika teacher in debate, and King of Kucha came to Turpan to ask Kumārajīva personally to return with him to Kucha city. Kumārajīva obliged and returned to instruct the king's daughter A-kie-ye-mo-ti, who had become a nun, in the and Avatamsaka Sutras.

At age 20, Kumārajīva was fully ordained at the king's palace, and lived in a new monastery built by king . Notably, he received who was his preceptor, a Sarvāstivādin monk from Kashmir, and was instructed by him in the Sarvāstivādin Vinaya Piṭaka. Kumārajīva proceeded to study the Pañcaviṁśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, one of the longer Prajñāpāramitā texts. He is known to have engaged in debates, and to have encouraged dialogue with foreign monks. Jīvaka is thought to have moved to Kashmir.

Capture, Imprisonment and Release[]

In 379 CE, Kumārajīva's fame reached China when a Chinese Buddhist monk named Seng Jun visited Kucha and described Kumārajīva's abilities. Efforts were then made by Emperor Fu Jian (苻堅) of the Former Qin Dynasty to bring Kumārajīva to Qin capital of Chang'an.[5] To do this, his general Lü Guang was dispatched with an army in order to conquer Kucha and return with Kumārajīva. Fu Jian is recorded as telling his general, "Send me Kumārajīva as soon as you conquer Kucha."[6] However, when Fu Jian's main army at the capital was defeated, his general Lü Guang declared his own state and became a warlord in 386 CE, and had Kumārajīva captured when he was around 40 years old.[7] Being a non-Buddhist, Lü Guang had Kumārajīva imprisoned for many years, essentially as booty. During this time, it is thought that Kumārajīva became familiar with the Chinese language. Kumarajiva was also coerced by Lü into marrying the Kucha King's daughter, which resulted in his chastity vow being negated.[8]

After the Yao family of Former Qin overthrew the previous ruler Fu Jian, the emperor Yao Xing made repeated pleas to the warlords of the Lü family to free Kumārajīva and send him east to Chang'an.[9] When the Lü family would not free Kumārajīva from their hostage, an exasperated Yao Xing had armies dispatched to Liangzhou in order to defeat the warlords of the Lü family and to have Kumārajīva brought back to them.[9] Finally the armies of Emperor Yao succeeded in defeating the Lü family, and Kumārajīva was brought east to the capital of Chang'an in 401 CE.[9]

At Chang'an[]

At Chang'an, Kumārajīva was immediately introduced to the emperor Yao Xing, the court, and the Buddhist leaders. He was hailed as a great master from the Western regions, and immediately took up a very high position in Chinese Buddhist circles of the time, being given the title of National Teacher. Yao Xing looked upon him as his own teacher, and many young and old Chinese Buddhists flocked to him, learning both from his direct teachings and through his translation bureau activities.

Kumārajīva appeared to have a major influence on Emperor Yao Xing's actions later on, as he avoided actions that may lead to many deaths, while trying to act gently toward his enemies. At his request, Kumārajīva translated many sutras into Chinese. Yao Xing also built many towers and temples. Because of the influence of Kumārajīva and Yao Xing, it was described that 90% of the population became Buddhists.

The second era of translators A. D. 400 was that of Kumaradjiva of Kashmir. There can be no doubt that he made use of SH and S as separate letters for he never confounds them in his choice of Chinese characters. The Chinese words already introduced by his predecessors he did not alter, and in introducing new terms required in the translation of the Mahayana literature, the texts of the 大乘 dasheng, or "greater vehicle," he uses SH for SH and usually B for V. Thus the city Shravasti was in Pali Savatthi and in Chinese 舍婆提 Sha-ba-ti. Probably Kumaradjiva himself speaking in the Cashmere dialect of Sanscrit called it Shabati.[10]

Translation style[]

Kumarajiva revolutionized Chinese Buddhism, in clarity and overcoming the previous "geyi" (concept-matching) system of translation through use of Daoist and Confucian terms. His translation style was distinctive, possessing a flowing smoothness that reflects his prioritization on conveying the meaning as opposed to precise literal rendering.[11] Because of this, his renderings of seminal Mahayana texts have often remained more popular than later, more literal translations, e.g. those of Xuanzang.[12] Sengrui had some influence on this final polished style, as the final editor of his translation works.

Kumarajiva has sometimes been regarded by both the Chinese and by western scholars as abbreviating his translations, with later translators such as Xuanzang being regarded as being more "precise." According to Jan Nattier, this is actually an erroneous and mistaken view, and the main difference was due to the earlier versions of Kumarajiva's source texts:

[W]here Kumarajiva's work can be compared with an extant Indic manuscript – that is, in those rare cases where part or all of a text he translated has survived in a Sanskrit or Prakrit version – a somewhat surprising result emerges. While his translations are indeed shorter in many instances than their extant (and much later) Sanskrit counterparts, when earlier Indic-language manuscript fragments are available they often provide exact parallels of Kumarajiva's supposed "abbreviations." What seems likely to have happened, in sum, is that Kumarajiva was working from earlier Indian versions in which these expansions had not yet taken place.[13]

Legacy[]

Among the most important texts translated by Kumārajīva are the Diamond Sutra, Amitabha Sutra, Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Nirdesa Sutra, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa which was a commentary (attributed to Nagarjuna) on the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

Kumarajiva had four main disciples: Daosheng (竺道生), Sengzhao (僧肇), (道融), and Sengrui (僧睿).

See also[]

- Chinese Translation Theory

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

References[]

- ^ Pollard 2015, p. 287.

- ^ Singh 2009, p. 523.

- ^ Chandra 1977, p. 180.

- ^ Smith 1971, p. 115.

- ^ Kumar 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Duan, Wenjie. Dunhuang Art: Through the Eyes of Duan Wenjie. 1995. p. 94

- ^ Nan 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Wu 1938, p. 455.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kumar 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Eitel & Edkins 1871, p. 217.

- ^ Nattier 1992, p. 186.

- ^ Nattier 1992, p. 188.

- ^ Nattier 2005, p. 60.

Sources[]

- Chandra, Moti (1977), Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9788170170556

- Eitel, E.J.; Edkins, Joseph (1871), "Handbook for the Student of Chinese Buddhism", The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal, FOOCHOW.: American Presbyterian Mission Press, 3: 217

- Kumar, Yukteshwar (2005), A History of Sino-Indian Relations, APH Publishing Corporation, ISBN 978-8176487986

- Lu, Yang (2004), "Narrative and Historicity in the Buddhist Biographies of Early Medieval China: The Case of Kumārajīva", Asia Major, Third Series, 17 (2): 1–43

- Nan, Huai-Chin (1998), Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen, ISBN 978-1578630202

- Nattier, Jan (1992), "The Heart Sutra: A Chinese Apocryphal Text?", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 15 (2): 153–223

- Nattier, Jan (2005), A Few Good Men: The Bodhisattva Path according to The Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipṛcchā), University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824830038

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2015), Worlds Together Worlds Apart, 500 Fifth Ave New York, NY: W.W. Norton Company Inc, p. 287, ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2CS1 maint: location (link)

- Puri, B. N. (1987), Buddhism in Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, ISBN 978-8120803725

- Singh, Upinder (2009), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-8131716779

- Smith, David Howard (1971), Chinese Religions From 1000 B.C. to the Present Day, Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Wu, Ching-hsing (1938), "Some Notes on Kao Seng Chuan", T'ien Hsia Monthly, Kelly and Walsh, ltd., 7

This article incorporates text from The Chinese recorder and missionary journal, Volume 3, a publication from 1871, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese recorder and missionary journal, Volume 3, a publication from 1871, now in the public domain in the United States.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kumarajiva. |

- Works by Kumārajīva at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kumārajīva at Internet Archive

- 344 births

- 413 deaths

- 4th-century Buddhist monks

- 5th-century Buddhist monks

- Buddhist monks from the Western Regions

- Chinese scholars of Buddhism

- Sixteen Kingdoms translators

- Later Liang (Sixteen Kingdoms) Buddhist monks

- Later Qin Buddhist monks

- Sanskrit–Chinese translators

- Chinese Buddhist missionaries

- Buddhist missionaries

- People from Aksu Prefecture

- Buddhist translators

- Chinese people of Kashmiri descent

- Writers from Xinjiang

- Former Qin Buddhist monks

- Philosophers from Xinjiang

- Madhyamaka scholars

- Missionary linguists