Mount Hudson

| Mount Hudson | |

|---|---|

| Cerro Hudson | |

Aerial photo from 1991 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,905 m (6,250 ft) |

| Coordinates | 45°54′S 72°58′W / 45.900°S 72.967°W |

| Geography | |

| Location | Chile |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Southern Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | 2011 |

Mount Hudson (Spanish: Volcán Hudson, Monte Hudson) is a stratovolcano in southern Chile, and the site of one of the largest eruptions in the twentieth century. The mountain itself is covered by a glacier. There is a caldera at the summit from an ancient eruption; modern volcanic activity comes from inside the caldera. Mount Hudson is named after Francisco Hudson, a 19th-century Chilean Navy hydrographer.

Eruptive history[]

The first large explosive eruption of the volcano dates, the "H0" eruption, to around 15,450 BCE.[1] Subsequent large eruptions around 4750 BCE and 1890 BCE are believed to have been of Volcanic explosivity index (VEI) 6; these are probably responsible for the large caldera. The 4750 BCE eruption, also known as "H1",[1] may have wiped out many or all of the groups living in central Patagonia at that time, based on evidence from the Los Toldos archaeological site,[2] and the sudden ceasing of rock art production in the area around that time.[3] The 1890 BCE eruption known as "H2" (ca. 3,900 a cal BP) is known to have deposited an ash layer of about 5 cm as far east as the shores of San Jorge Gulf in the Atlantic coast.[1] Recently, the volcano has had moderate eruptions in 1891 and 1971 as well as a large eruption in 1991. This last eruption is known as "H3".[1]

1971 eruption[]

Before 1970, little was known about the mountain. Minor eruptive activity began in 1970 and melted parts of the glacier, raising river water levels and leading to the identification of the caldera. In August–September 1971, a moderate eruption (VEI 3) located in the northwest area of the caldera sent ash into the air and caused lahars from the melting of a large portion of the glacier. The lahars killed five people; many more were evacuated.

1991 eruption[]

The eruption in August to October 1991 was a large plinian eruption with a VEI of 5, that ejected 4.3 km3 bulk volume (2.7 cubic km of dense rock equivalent material).[4] Parts of the glacier melted and ran down the mountain as mud flows (see glacier run). Due to the remoteness of the area, no-one was killed but hundreds of people were evacuated from the vicinity. Ash fell on Chile and Argentina as well as in the South Atlantic Ocean and on the Falkland Islands.[5] In 1992, John Locke Blake, then resident on Estancia Condor, south of Rio Gallegos, in Argentina describes the effects of the eruption vividly.[6] He describes an ash fall up to 15 cm in depth, covering some 150,000 to 180,000 square kilometres in a triangle from Los Antiguos to Deseado to San Julian to a depth of between 5 and 10 cm. He reports that the hygroscopicity of the silica caused the formation of morasses around drinking places causing sheep to be trapped and die in huge numbers. He records that 'ten years later, most of the farms in the affected area are empty, of sheep and of people'.

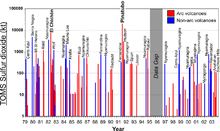

In addition to the ash, a large amount of sulfur dioxide gas and aerosols were ejected in the eruption. These contributed to those already in the atmosphere from the even larger 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo earlier in the year and helped cause a worldwide cooling effect over the following years. Ozone was also depleted, with the Antarctic ozone hole growing to its largest levels ever recorded in 1992 and 1993.

As a result of the Mount Pinatubo eruption, the Hudson eruption received little attention at the time.

October–November 2011 eruption[]

On October 26, the Chilean Service for Geology and Minery issued a red alert and a mass evacuation of the region surrounding the volcano, fearing an imminent eruption in the coming hours or days.[7] It happened on Oct 31 but was small and didn't do any damage to the area.[8]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Zanchetta, Zanchetta; Pappalardo, Marta; Di Roberto, Alessio; Bini, Monica; Arienzo, Ilenia; Isola, Ilaria; Ribolini, Adriano; Boretto, Gabriella; Fuck, Enrique; Mele, Daniela; D’Orazio, Massimo; Marzaioli, Fabio; Passariello, Isabella (2021-05-01). "A Holocene tephra layer within coastal aeolian deposits north of Caleta Olivia (Santa Cruz Province, Argentina)". Andean Geology. 48 (2): 267–280. doi:10.5027/andgeoV48n2-3290.

- ^ Cardich, A. (1985) "Una fecha radiocarbonica mas de la cueva 3 de Los Toldos (Santa Cruz, Argentina)" Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología, Nueva Serie 16: 269-275

- ^ Aschero, Carlos A. (2018). "Hunting scenes in Cueva de las Manos: Styles, content and chronology (Río Pinturas, Santa Cruz – Argentinian Patagonia)". In Troncoso, Andrés; Armstrong, Felipe; Nash, George (eds.). Archaeologies of rock art: South American Perspectives. London: Routledge. p. 234. doi:10.4324/9781315232782-9. ISBN 9781138292673. OCLC 975369942. S2CID 189442969.

- ^ Kratzmann, David, et al. (2009) "Compositional variations and magma mixing in the 1991 eruptions of Hudson volcano, Chile" Bulletin of Volcanology 71(4): pp. 419–439, p.419, doi:10.1007/s00445-008-0234-x

- ^ Scasso, Roberto A.; Corbella, Hugo and Tiberi, Pedro (1994) "Sedimentological analysis of the tephra from the 12–15 August 1991 eruption of Hudson volcano" Bulletin of volcanology 56(2): pp. 121–132, doi:10.1007/BF00304107

- ^ Blake, John Locke; The Book Guild (2003) "A Story of Patagonia" pp. 402-403, ISBN I 85776 697 0

- ^ "Reporte Especial Nº23 Actividad Volcánica Región de Aysén: Volcán Hudson". Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería. 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ "Global Volcanism Program | Cerro Hudson".

External links[]

- Mountains of Aysén Region

- Stratovolcanoes of Chile

- Active volcanoes

- Subduction volcanoes

- VEI-6 volcanoes

- Volcanoes of Aysén Region

- South Volcanic Zone

- 20th-century volcanic events