Myocarditis

| Myocarditis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Inflammatory cardiomyopathy (infectious) |

| |

| A microscope image of myocarditis at autopsy in a person with acute onset of heart failure | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, cardiology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, chest pain, decreased ability to exercise, irregular heartbeat[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrest[1] |

| Duration | Hours to months[1] |

| Causes | Usually viral infection, also bacterial infections, certain medications, toxins, autoimmune disorders[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Electrocardiogram, blood troponin, heart MRI, heart biopsy[1][2] |

| Treatment | Medications, implantable cardiac defibrillator, heart transplant[1][2] |

| Medication | ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, diuretics, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Variable[3] |

| Frequency | 2.5 million with cardiomyopathy (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 354,000 with cardiomyopathy (2015)[5] |

Myocarditis, also known as inflammatory cardiomyopathy, is inflammation of the heart muscle. Symptoms can include shortness of breath, chest pain, decreased ability to exercise, and an irregular heartbeat.[1] The duration of problems can vary from hours to months. Complications may include heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy or cardiac arrest.[1]

Myocarditis is most often due to a viral infection.[1] Other causes include bacterial infections, certain medications, toxins, and autoimmune disorders.[1][2] A diagnosis may be supported by an electrocardiogram (ECG), increased troponin, heart MRI, and occasionally a heart biopsy.[1][2] An ultrasound of the heart is important to rule out other potential causes such as heart valve problems.[2]

Treatment depends on both the severity and the cause.[1][2] Medications such as ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, and diuretics are often used.[1][2] A period of no exercise is typically recommended during recovery.[1][2] Corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) may be useful in certain cases.[1][2] In severe cases an implantable cardiac defibrillator or heart transplant may be recommended.[1][2]

In 2013, about 1.5 million cases of acute myocarditis occurred.[6] While people of all ages are affected, the young are most often affected.[7] It is slightly more common in males than females.[1] Most cases are mild.[2] In 2015 cardiomyopathy, including myocarditis, resulted in 354,000 deaths up from 294,000 in 1990.[8][5] The initial descriptions of the condition are from the mid-1800s.[9]

Signs and symptoms[]

The signs and symptoms associated with myocarditis are varied, and relate either to the actual inflammation of the myocardium or to the weakness of the heart muscle that is secondary to the inflammation. Signs and symptoms of myocarditis include the following:[10]

- Chest pain (often described as "stabbing" in character)

- Congestive heart failure (leading to swelling, shortness of breath and liver congestion)

- Palpitations (due to abnormal heart rhythms)

- Dullness of heart sounds

- Sudden death (in young adults, myocarditis causes up to 20% of all cases of sudden death)[11]

- Fever (especially when infectious, e.g., in rheumatic fever)

- Symptoms in young children tend to be more nonspecific, with generalized malaise, poor appetite, abdominal pain, and chronic cough. Later stages of the illness will present with respiratory symptoms with increased work of breathing, and are often mistaken for asthma.

Since myocarditis is often due to a viral illness, many patients give a history of symptoms consistent with a recent viral infection, including fever, rash, diarrhea, joint pains, and easily becoming tired.[12]

Myocarditis is often associated with pericarditis, and many people with myocarditis present with signs and symptoms that suggest myocarditis and pericarditis at the same time.[13][14]

Causes[]

A large number of causes of myocarditis have been identified, but often a cause cannot be found. In Europe and North America, viruses are common culprits. Worldwide, however, the most common cause is Chagas disease, an illness endemic to Central and South America that is due to infection by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi.[10] In viral myocarditis, the Coxsackie B family of the single-stranded RNA viruses, in particular the plus-strand RNA virus Coxsackievirus B3 and Coxsackievirus B5 are the most frequent cause.[15] Many of the causes listed below, particularly those involving protozoa, fungi, parasites, allergy, autoimmune disorders, and drugs are also causes of eosinophilic myocarditis.[16][17]

Infections[]

- Viral: adenovirus,[18] parvovirus B19, coxsackie virus, rubella virus, polio virus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis C, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2)[19][20]

- Protozoan: Trypanosoma cruzi (causing Chagas disease) and Toxoplasma gondii

- Bacterial: Brucella, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, gonococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Actinomyces, Tropheryma whipplei, Vibrio cholerae, Borrelia burgdorferi, leptospirosis, Rickettsia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Fungal: Aspergillus

- Parasitic: ascaris, Echinococcus granulosus, Paragonimus westermani, schistosoma, Taenia solium, Trichinella spiralis, visceral larva migrans, Wuchereria bancrofti

Bacterial myocarditis is rare in patients without immunodeficiency.

Toxins[]

- Drugs, including alcohol, anthracyclines and some other forms of chemotherapy, and antipsychotics, e.g., clozapine, also some designer drugs such as mephedrone[21]

Immunologic[]

- Allergic (acetazolamide, amitriptyline)

- Rejection after a heart transplant

- Autoantigens (scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, systemic vasculitis such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Kawasaki disease, idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome)[22]

- Toxins (arsenic, toxic shock syndrome toxin, carbon monoxide, or snake venom)

- Heavy metals (copper or iron)

- Vaccination against smallpox[23] and Covid19,[24][25] rarely, but not other vaccines

Physical agents[]

- Electric shock, hyperpyrexia, and radiation

Mechanism[]

Most forms of myocarditis involve the infiltration of heart tissues by one or two types of pro-inflammatory blood cells, lymphocytes and macrophages plus two respective descendants of these cells, NK cells and macrophages. Eosinophilic myocarditis is a subtype of myocarditis in which cardiac tissue is infiltrated by another type of pro-inflammatory blood cell, the eosinophil. Eosinophilic myocarditis is further distinguished from non-eosinophilic myocarditis by having a different set of causes and recommended treatments.[26][27] Coxsackie B, specifically B3 and B5, has been found to interact with coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR) and decay-accelerating factor (DAF). However, other proteins have also been identified that allow Coxsackieviruses to bind to cardiac cells. The natural function of CAR and mechanism that the Coxsackievirus uses to infect the cardiac muscle is still unknown.[15] The mechanism by which coxsackie B viruses (CBVs) trigger inflammation is believed to be through the recognition of CBV virions by Toll-like receptors.[15]

The binding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus through ACE2 receptors present in heart tissue may be responsible for direct viral injury leading to myocarditis.[20] In a study done during the SARS outbreak, SARS virus RNA was ascertained in the autopsy of heart specimens in 35% of the patients who died due to SARS.[28] It was also observed that an already diseased heart has increased expression of ACE2 receptor contrasted to healthy individuals. Hyperactive immune responses in Covid-19 Patients may lead to the initiation of the cytokine storm. This excess release of cytokines may lead to myocardial injury.[20]

Diagnosis[]

Myocarditis refers to an underlying process that causes inflammation and injury of the heart. It does not refer to inflammation of the heart as a consequence of some other insult. Many secondary causes, such as a heart attack, can lead to inflammation of the myocardium and therefore the diagnosis of myocarditis cannot be made by evidence of inflammation of the myocardium alone.[29][30]

Myocardial inflammation can be suspected on the basis of electrocardiographic (ECG) results, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and increased IgM (serology) against viruses known to affect the myocardium. Markers of myocardial damage (troponin or creatine kinase cardiac isoenzymes) are elevated.[10]

The ECG findings most commonly seen in myocarditis are diffuse T wave inversions; saddle-shaped ST-segment elevations may be present (these are also seen in pericarditis).[10]

The gold standard is the biopsy of the myocardium, in general done in the setting of angiography. A small tissue sample of the endocardium and myocardium is taken and investigated. The cause of the myocarditis can be only diagnosed by a biopsy. Endomyocardial biopsy samples are assessed for histopathology (how the tissue looks like under the microscope: myocardial interstitium may show abundant edema and inflammatory infiltrate, rich in lymphocytes and macrophages. Focal destruction of myocytes explains the myocardial pump failure.[10] In addition samples may be assessed with immunohistochemistry to determine which types of immune cells are involved in the reaction and how they are distributed. Furthermore, PCR and/or RT-PCR may be performed to identify particular viruses. Finally, further diagnostic methods like microRNA assays and gene-expression profile may be performed.[citation needed]

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI or CMR) has been shown to be very useful in diagnosing myocarditis by visualizing markers for inflammation of the myocardium.[31] Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of myocarditis by CMR were published in 2009.[32]

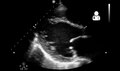

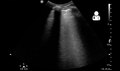

Ultrasound showing cardiogenic shock due to myocarditis[33]

Ultrasound showing cardiogenic shock due to myocarditis[33]

Ultrasound showing cardiogenic shock due to myocarditis[33]

Treatment[]

As with most viral infections, symptomatic treatment is the only form of therapy for most forms of myocarditis.[34] In the acute phase, supportive therapy, including bed rest, is indicated.[citation needed]

Medication[]

In people with symptoms, digoxin and diuretics may help. For people with moderate to severe dysfunction, cardiac function can be supported by use of inotropes such as milrinone in the acute phase, followed by oral therapy with ACE inhibitors when tolerated.[35]

Systemic corticosteroids may have beneficial effects in people with proven myocarditis.[36] However, data on the usefulness of corticosteroids should be interpreted with caution, since 58% of adults recover spontaneously, while most studies on children lack control groups.[34]

A 2015 Cochrane review found no evidence of benefit of using intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in adults and tentative benefit in certain children.[37] It is not recommended routinely until there is better evidence.[37]

Surgery[]

People who do not respond to conventional therapy may be candidates for bridge therapy with left ventricular assist devices. Heart transplantation is reserved for people who fail to improve with conventional therapy.[36]

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be used in those who are about to go into cardiac arrest.[38]

Alternative medicine[]

Studies have shown no benefit for the use of herbal medicine on all-cause mortality in viral myocarditis.[39]

Epidemiology[]

The exact incidence of myocarditis is unknown. However, in series of routine autopsies, 1–9% of all patients had evidence of myocardial inflammation. In young adults, up to 20% of all cases of sudden death are due to myocarditis.[10]

Among patients with HIV, myocarditis is the most common cardiac pathological finding at autopsy, with a prevalence of 50% or more.[40]

Myocarditis is the third most common cause of death among young adults with a cumulative incidence rate globally of 1.5 cases per 100,000 persons annually.[41] Myocarditis accounts for approximately 20% of sudden cardiac death in a variety of populations.[10] Populations that experience this increased mortality rate include: adults under 40, young athletes, U.S. Air Force recruits, and elite Swedish orienteers.[10] The prevalence rate of myocarditis is about 22 cases per 100,000 persons annually.[42] With individuals who develop myocarditis, the first year is difficult as a collection of cases have shown there is a 20% mortality rate.[43]

One rare instance of myocarditis is viral fulminant myocarditis; fulminant myocarditis involves rapid onset cardiac inflammation and a mortality rate of 40-70%.[44] When looking at different causes of myocarditis, viral infection is the most prevalent, especially in children; however, the prevalence rate of myocarditis is often underestimated since the condition is easily overlooked.[42] Viral myocarditis being an outcome of viral infection depends heavily on genetic host factors and the pathogenicity unique to the virus.[45] One notable instance of viral myocarditis is the involvement of the SARS-CoV-2 virus; fulminant myocarditis from cardiac damage and SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with high mortality rates.[44] Myocarditis can also, rarely, be caused by vaccination against Covid-19;[24][25] however, the risk of myocarditis due to vaccination is less than the risk of myocarditis following infection,[46] and far less than the risks of other harm due to infection. Some incidences of acute myocarditis can be attributed to the exposure of drugs or toxic substances and abnormal immunoreactivity.[47] The following agents may be other causes of myocarditis in various populations also, as previously highlighted in a prior section: protozoa, viruses, bacteria, rickettsia, and fungi.[42] If one tests positive for an acute viral infection, clinical developments have discovered that 1% to 5% of said population may show some form of myocarditis.[42]

When looking at the population affected, myocarditis is more common in pregnant women in addition to children and those who are immunocompromised.[41] Myocarditis, however, has shown to be more common in the male population than in the female.[42] Multiple studies report a ratio of 1:1.3-1.7 of female-male prevalence of myocarditis.[48] Young males specifically have a higher incidence rate than any other population due to their testosterone levels creating a greater inflammatory response that increases chance of cardiac pathologies such as cardiomyopathy, heart failure, or myocarditis.[42] While males tend to have a higher tendency of developing myocarditis, females tend to display more severe signs and symptoms such as ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation at an older age.[42] Clinical patterns can assist in the diagnosis of myocarditis among the affected population. Due to the asymptomatic nature of Myocarditis, much information about the epidemiology of the disease is due to postmortem research.[10] In a study of 3,055 patients with acute or chronic myocarditis, 72% presented with difficulty or labored breathing, 32% with chest pain, and another 18% with arrhythmias.[42] Clinical observation suggests the possibility of a relationship between immunization and cardiac related symptoms; myocarditis and pericarditis have been observed to have a 200 times higher incidence rate post smallpox vaccine compared to pre smallpox vaccine.[49]

History[]

Cases of myocarditis have been documented as early as the 1600s,[50] but the term "myocarditis", implying an inflammatory process of the myocardium, was introduced by German physician Joseph Friedrich Sobernheim in 1837.[51] However, the term has been confused with other cardiovascular conditions, such as hypertension and ischemic heart disease.[52] Following admonition regarding the indiscriminate use of myocarditis as a diagnosis from authorities such as British cardiologist Sir Thomas Lewis and American cardiologist and a co-founder of the American Heart Association Paul White, myocarditis was under-diagnosed.[52]

Although myocarditis is clinically and pathologically clearly defined as "inflammation of the myocardium", its definition, classification, diagnosis, and treatment are subject to continued controversy, but endomyocardial biopsy has helped define the natural history of myocarditis and clarify clinicopathological correlations.[53]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Cooper LT (April 2009). "Myocarditis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (15): 1526–38. doi:10.1056/nejmra0800028. PMC 5814110. PMID 19357408.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kindermann I, Barth C, Mahfoud F, Ukena C, Lenski M, Yilmaz A, et al. (February 2012). "Update on myocarditis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 59 (9): 779–92. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.074. PMID 22361396.

- ^ Stouffer G, Runge MS, Patterson C (2010). Netter's Cardiology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 181. ISBN 9781437736502.

- ^ Vos, Theo; Allen, Christine; Arora, Megha; Barber, Ryan M.; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A.; Brown, Alexandria; Carter, Austin; Casey, Daniel C.; Charlson, Fiona J.; Chen, Alan Z.; Coggeshall, Megan; Cornaby, Leslie; Dandona, Lalit; Dicker, Daniel J.; Dilegge, Tina; Erskine, Holly E.; Ferrari, Alize J.; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Fleming, Tom; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H.; Fullman, Nancy; Gething, Peter W.; Goldberg, Ellen M.; Graetz, Nicholas; Haagsma, Juanita A.; Hay, Simon I.; Johnson, Catherine O.; Kassebaum, Nicholas J.; Kawashima, Toana; et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Jump up to: a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Vos, Theo; Barber, Ryan M.; Bell, Brad; Bertozzi-Villa, Amelia; Biryukov, Stan; Bolliger, Ian; Charlson, Fiona; Davis, Adrian; Degenhardt, Louisa; Dicker, Daniel; Duan, Leilei; Erskine, Holly; Feigin, Valery L.; Ferrari, Alize J.; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Fleming, Thomas; Graetz, Nicholas; Guinovart, Caterina; Haagsma, Juanita; Hansen, Gillian M.; Hanson, Sarah Wulf; Heuton, Kyle R.; Higashi, Hideki; Kassebaum, Nicholas; Kyu, Hmwe; Laurie, Evan; Liang, Xiofeng; Lofgren, Katherine; Lozano, Rafael; et al. (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Willis M, Homeister JW, Stone JR (2013). Cellular and Molecular Pathobiology of Cardiovascular Disease. Academic Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780124055254. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Cunha BA (2009). Infectious Diseases in Critical Care Medicine. CRC Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781420019605. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Feldman AM, McNamara D (November 2000). "Myocarditis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (19): 1388–98. doi:10.1056/NEJM200011093431908. PMID 11070105.

- ^ Eckart RE, Scoville SL, Campbell CL, Shry EA, Stajduhar KC, Potter RN, et al. (December 2004). "Sudden death in young adults: a 25-year review of autopsies in military recruits". Annals of Internal Medicine. 141 (11): 829–34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00005. PMID 15583223.

- ^ "Myocarditis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Pericarditis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 23 July 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Myocarditis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marín-García J (2007). Post-Genomic Cardiology. Academic Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-0123736987.

- ^ Séguéla PE, Iriart X, Acar P, Montaudon M, Roudaut R, Thambo JB (2015). "Eosinophilic cardiac disease: Molecular, clinical and imaging aspects". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 108 (4): 258–68. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2015.01.006. PMID 25858537.

- ^ Rose NR (2016). "Viral myocarditis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 28 (4): 383–9. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000303. PMC 4948180. PMID 27166925.

- ^ Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, Pauschinger M, Schultheiss HP, McCarthy R; et al. (2003). "Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction. evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults". J Am Coll Cardiol. 42 (3): 466–72. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00648-x. PMID 12906974.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Sheppard M (2011). Practical Cardiovascular Pathology, 2nd edition. CRC Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780340981931.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rathore, Sawai Singh; Rojas, Gianpier Alonzo; Sondhi, Manush; Pothuru, Suveenkrishna; Pydi, Reshma; Kancherla, Neeraj; Singh, Romil; Ahmed, Noman Khurshid; Shah, Jill; Tousif, Sohaib; Baloch, Unaiza Tariq (2021). "Myocarditis associated with Covid-19 disease: A systematic review of published case reports and case series". International Journal of Clinical Practice. n/a (n/a): e14470. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14470. ISSN 1742-1241. PMID 34235815. S2CID 235768792.

- ^ Nicholson PJ, Quinn MJ, Dodd JD (December 2010). "Headshop heartache: acute mephedrone 'meow' myocarditis". Heart. 96 (24): 2051–2. doi:10.1136/hrt.2010.209338. PMID 21062771. S2CID 36684597.

- ^ Dinis P, Teixeira R, Puga L, Lourenço C, Cachulo MC, Gonçalves L (June 2018). "Eosinophilic Myocarditis: Clinical Case and Literature Review". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 110 (6): 597–599. doi:10.5935/abc.20180089. PMC 6023626. PMID 30226920.

- ^ Dudley, Matthew Z.; Salmon, Daniel A.; Halsey, Neal A.; Orenstein, Walter A.; Limaye, Rupali J.; O'Leary, Sean T.; Omer, Saad B. (2018). "Do Vaccines Cause Myocarditis or Myocardopathy/Cardiomyopathy?". The Clinician's Vaccine Safety Resource Guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 305–308. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94694-8_45. ISBN 978-3-319-94693-1.

Smallpox vaccine does very rarely cause myocarditis and myocardopathy/cardiomyopathy ... Other vaccines ... have not been shown to cause [these]. [Note 2018, pre-covid source]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nevet, Alon (31 May 2021). "Acute myocarditis associated with anti-COVID-19 vaccination". Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research. 10 (2): 196–197. doi:10.7774/cevr.2021.10.2.196. PMC 8217579. PMID 34222133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoeg, Tracy Beth; Krug, Allison; Stevenson, Josh; Mandrola, John (8 September 2021), SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination-Associated Myocarditis in Children Ages 12-17: A Stratified National Database Analysis (preprint), medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.08.30.21262866

- ^ Séguéla PE, Iriart X, Acar P, Montaudon M, Roudaut R, Thambo JB (April 2015). "Eosinophilic cardiac disease: Molecular, clinical and imaging aspects". Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 108 (4): 258–68. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2015.01.006. PMID 25858537.

- ^ Rose NR (July 2016). "Viral myocarditis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 28 (4): 383–9. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000303. PMC 4948180. PMID 27166925.

- ^ Oudit, G. Y.; Kassiri, Z.; Jiang, C.; Liu, P. P.; Poutanen, S. M.; Penninger, J. M.; Butany, J. (July 2009). "SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 39 (7): 618–625. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02153.x. ISSN 1365-2362. PMC 7163766. PMID 19453650.

- ^ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 414–416. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ Baughman KL (January 2006). "Diagnosis of myocarditis: death of Dallas criteria". Circulation. 113 (4): 593–5. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.589663. PMID 16449736.

- ^ Skouri HN, Dec GW, Friedrich MG, Cooper LT (November 2006). "Noninvasive imaging in myocarditis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 48 (10): 2085–93. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.017. PMID 17112998.

- ^ Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT, et al. (April 2009). "Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: A JACC White Paper". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 53 (17): 1475–87. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.007. PMC 2743893. PMID 19389557.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "UOTW #7 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hia CP, Yip WC, Tai BC, Quek SC (June 2004). "Immunosuppressive therapy in acute myocarditis: an 18 year systematic review". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 89 (6): 580–4. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.034686. PMC 1719952. PMID 15155409.

- ^ "Myocarditis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aziz KU, Patel N, Sadullah T, Tasneem H, Thawerani H, Talpur S (October 2010). "Acute viral myocarditis: role of immunosuppression: a prospective randomised study". Cardiology in the Young. 20 (5): 509–15. doi:10.1017/S1047951110000594. PMID 20584348. S2CID 46176024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robinson J, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Sebastianski M, Klassen TP (August 2020). "Intravenous immunoglobulin for presumed viral myocarditis in children and adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD004370. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004370.pub4. PMC 8210245. PMID 32835416.

- ^ de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, Gooden CK, Hickey RW, Scott HF, et al. (November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526-42. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000266. PMC 6191296. PMID 26473000.

- ^ Liu ZL, Liu ZJ, Liu JP, Kwong JS (August 2013). Liu JP (ed.). "Herbal medicines for viral myocarditis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD003711. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003711.pub5. PMID 23986406.

- ^ Cooper LT (April 2009). "Myocarditis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (15): 1526–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0800028. PMC 5814110. PMID 19357408.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kang M, An J (2020). "Viral Myocarditis". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29083732. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Fung G, Luo H, Qiu Y, Yang D, McManus B (February 2016). "Myocarditis". Circulation Research. 118 (3): 496–514. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306573. PMID 26846643.

- ^ Sharma AN, Stultz JR, Bellamkonda N, Amsterdam EA (December 2019). "Fulminant Myocarditis: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management". The American Journal of Cardiology. 124 (12): 1954–1960. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.09.017. PMID 31679645.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang DW (May 2020). "SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis". Herz. 45 (3): 230–232. doi:10.1007/s00059-020-04909-z. PMC 7080076. PMID 32140732.

- ^ Pankuweit S, Klingel K (November 2013). "Viral myocarditis: from experimental models to molecular diagnosis in patients". Heart Failure Reviews. 18 (6): 683–702. doi:10.1007/s10741-012-9357-4. PMID 23070541. S2CID 36633104.

- ^ Wilson, Clare (4 August 2021). "Myocarditis is more common after covid-19 infection than vaccination". New Scientist.

- ^ Ammirati E, Veronese G, Bottiroli M, Wang DW, Cipriani M, Garascia A, et al. (June 2020). "Update on acute myocarditis". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 31 (6): 370–379. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2020.05.008. PMC 7263216. PMID 32497572.

- ^ Fairweather D, Cooper LT, Blauwet LA (January 2013). "Sex and gender differences in myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy". Current Problems in Cardiology. 38 (1): 7–46. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2012.07.003. PMC 4136454. PMID 23158412.

- ^ Engler RJ, Nelson MR, Collins LC, Spooner C, Hemann BA, Gibbs BT, et al. (2015-03-20). "A prospective study of the incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis and new onset cardiac symptoms following smallpox and influenza vaccination". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118283. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018283E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118283. PMC 4368609. PMID 25793705.

- ^ P. Schölmerich. (1983.) "Myocarditis — Cardiomyopathy Historic Survey and Definition", International Boehringer Mannheim Symposia, 1:5.

- ^ Joseph Friedrich Sobernheim. (1837.) Praktische Diagnostik der inneren Krankheiten mit vorzueglicher Ruecksicht auf pathologische Anatomic. Hirschwald, Berlin, 117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olsen EG (1985). "What is myocarditis?". Heart and Vessels. 1 (1): S1-3. doi:10.1007/BF02072348. S2CID 189916609.

- ^ Magnani JW, Dec GW (February 2006). "Myocarditis: current trends in diagnosis and treatment". Circulation. 113 (6): 876–90. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584532. PMID 16476862. S2CID 1085693.

External links[]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Chronic rheumatic heart diseases

- Heart diseases

- Inflammations