Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture

The term Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture,[1] Norman-Sicilian culture[2] or, less inclusively, Norman-Arab culture,[3] (sometimes referred to as the "Arab-Norman civilization")[4][5][6][7] refers to the interaction of the Norman, Latin, Arab and Byzantine Greek cultures following the Norman conquest of Sicily and of Norman Africa from 1061 to around 1250. The civilization resulted from numerous exchanges in the cultural and scientific fields, based on the tolerance showed by the Normans towards the Greek-speaking populations and the Muslim settlers.[8] As a result, Sicily under the Normans became a crossroad for the interaction between the Norman and Latin Catholic, Byzantine-Orthodox and Arab-Islamic cultures.

Norman conquest of Southern Italy[]

Norman conquest of Sicily[]

In 965 Muslims completed their conquest of Sicily from the Byzantine Empire following the fall of the final significant Greek citadel of Taormina in 962.[citation needed] Seventy three years later, in 1038, Byzantine forces began a reconquest of Sicily under the Byzantine general George Maniakes. This invasion relied on a number of Norse mercenaries, the Varangians, including the future king of Norway Harald Hardrada, as well as on several contingents of Normans. Although Maniakes' death in a Byzantine civil war in 1043 cut the invasion short, the Normans followed up on the advances made by the Byzantines and completed the conquest of the island from the Saracens. The Normans had been expanding south, as mercenaries and adventurers, driven by the myth of a happy and sunny island in the Southern Seas.[9] The Norman Robert Guiscard, son of Tancred, invaded Sicily in 1060. The island was split politically between three Arab emirs, and the sizable Byzantine Christian population rebelled against the ruling Muslims. One year later Messina fell to troops under the leadership of Roger Bosso (the brother of Robert Guiscard and the future Count Roger I of Sicily), and in 1071 the Normans took Palermo.[10] The loss of the cities, each with a splendid harbor, dealt a severe blow to Muslim power on the island. Eventually Normans took all of Sicily. In 1091, Noto in the southern tip of Sicily and the island of Malta, the last Arab strongholds, fell to the Christians.

Norman conquest of Africa[]

The Kingdom of Africa was an extension of the frontier zone of the Siculo-Norman state in the former Roman province of Africa[a] (Ifrīqiya in Tunisian Arabic), corresponding to Tunisia and parts of Algeria and Libya today. The main primary sources for the kingdom are Arabic (Muslim);[11] the Latin (Christian) sources are scanter. According to Hubert Houben, since "Africa" was never mentioned in the royal title of the kings of Sicily, "one ought not to speak of a ‘Norman kingdom of Africa’."[12] Rather, "[Norman Africa] really amounted to a constellation of Norman-held towns along coastal Ifrīqiya."[13]

The Sicilian conquest of Africa began under Roger II in 1146–48. Sicilian rule consisted of military garrisons in the major towns, exactions on the local Muslim population, protection of Christians and the minting of coin. The local aristocracy was largely left in place, and Muslim princes controlled the civil government under Sicilian oversight. Economic connections between Sicily and Africa, which were strong before the conquest, were strengthened, while ties between Africa and northern Italy were expanded. Early in the reign of William I, the "kingdom" of Africa fell to the Almohads (1158–60). Its most enduring legacy was the realignment of Mediterranean powers brought about by its demise and the Siculo-Almohad peace finalised in 1180.

Cultural interactions[]

An intense Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture developed, exemplified by rulers such as Roger II of Sicily, who had Islamic soldiers, poets and scientists at his court,[14] and had Byzantine Greeks, Christodoulos, the famous George of Antioch, and finally Philip of Mahdia, serve successively as his ammiratus ammiratorum ("emir of emirs").[15] Roger II himself spoke Arabic and was fond of Arab culture.[16] He used Arab and Byzantine Greek troops and siege engines in his campaigns in southern Italy, and mobilized Arab and Byzantine architects to help his Normans build monuments in the Norman-Arab-Byzantine style. The various agricultural and industrial techniques which had been introduced by the Arabs in Sicily during the preceding two centuries were kept and further developed, allowing for the remarkable prosperity of the Island.[17] Numerous Classical Greek works, long lost to the Latin speaking West, were translated from Byzantine Greek manuscripts found in Sicily directly into Latin.[18] For the following two hundred years, Sicily under Norman rule became a model which was widely admired throughout Europe and Arabia.[19]

The English historian John Julius Norwich remarked of the Kingdom of Sicily:

Norman Sicily stood forth in Europe --and indeed in the whole bigoted medieval world-- as an example of tolerance and enlightenment, a lesson in the respect that every man should feel for those whose blood and beliefs happen to differ from his own.

John Julius Norwich[20]

During Roger II's reign, the Kingdom of Sicily became increasingly characterized by its multi-ethnic composition and unusual religious tolerance.[21] Catholic Normans, Langobards and native Sicilians, Muslim Arabs, and Orthodox Byzantine Greeks existed in a relative harmony for this time period,[22][23] and Roger II was known to have planned for the establishment of an Empire that would have encompassed Fatimid Egypt and the Crusader states in the Levant up until his death in 1154.[24] One of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages was written for Roger II by the Andalusian scholar Muhammad al-Idrisi, and entitled Kitab Rudjdjar ("The book of Roger").[25]

At the end of the 12th century, the population of Sicily is estimated to have been up to one-third Byzantine Greek speaking, with the remainder speaking Latin or Vulgar Latin dialects brought from mainland Italy (Gallo-Italic languages and Neapolitan language), Norman and Sicilian Arabic.[26] Although the language of the court was Old Norman or Old French (Langue d'oïl), all royal edicts were written in the language of the people they were addressed to: Latin, Byzantine Greek, Arabic, or Hebrew.[27] Roger's royal mantel, used for his coronation (and also used for the coronation of Frederick II), bore an inscription in Arabic with the Hijri date of 528 (1133–1134).

Islamic authors marvelled at the forbearance of the Norman kings:

They [the Muslims] were treated kindly, and they were protected, even against the Franks. Because of that, they had great love for king Roger.

Ibn al-Athir[28]

Interactions continued with the succeeding Norman kings, for example under William II of Sicily, as attested by the Spanish-Arab geographer Ibn Jubair who landed in the island after returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1184. To his surprise, Ibn Jubair enjoyed a very warm reception by the Norman Christians. He was further surprised to find that even some Christians spoke Arabic and that several government officials were Muslim:[25]

The attitude of the king is really extraordinary. His attitude towards the Muslims is perfect: he gives them employment, he chooses his officers among them, and all, or almost all, keep their faith secret and can remain faithful to the faith of Islam. The king has full confidence in the Muslims and relies on them to handle many of his affairs, including the most important ones, to the point that the Great Intendant for cooking is a Muslim (...) His viziers and chamberlains are eunuchs, of which there are many, who are the members of his government and on whom he relies for his private affairs.

Ibn Jubair, Rihla.[29]

Ibn Jubair mentioned that some Christians in Palermo wore the Muslim dress and spoke Arabic. The Norman kings continued to strike coins in Arabic with Hegira dates. The registers at the Royal court were written in Arabic.[25] At one point, William II of Sicily is recorded to have said: "Every one of you should invoke the one he adores and of whom he follows the faith".[30]

Norman-Arab-Byzantine art[]

Numerous artistic techniques from the Byzantine and Islamic world were also incorporated to form the basis of Arab-Norman art: inlays in mosaics or metals, sculpture of ivory or porphyry, sculpture of hard stones, bronze foundries, manufacture of silk (for which Roger II established a regium ergasterium, a state enterprise which would give Sicily the monopoly of silk manufacture for all Western Europe).[32] During a raid on the Byzantine Empire, Roger II's admiral George of Antioch had transported the silk weavers from Thebes, Greece, where they had formed a part of the, until then, closely guarded monopoly that was the Byzantine silk industry.

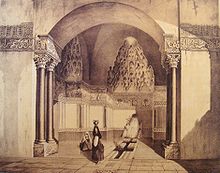

Norman-Arab-Byzantine architecture[]

The new Norman rulers started to build various constructions in what is called the Arab-Norman style. They incorporated the best practices of Arab and Byzantine architecture into their own art.[33]

The Church of Saint-John of the Hermits, was built in Palermo by Roger II around 1143–1148 in such a style. The church is notable for its brilliant red domes, which show clearly the persistence of Arab influences in Sicily at the time of its reconstruction in the 12th century. In her Diary of an Idle Woman in Sicily, Frances Elliot described it as "... totally oriental... it would fit well in Baghdad or Damascus". The bell tower, with four orders of arcaded loggias, is instead a typical example of Gothic architecture.

The Cappella Palatina, also in Palermo, combines harmoniously a variety of styles: the Norman architecture and door decor, the Arabic arches and scripts adorning the roof, the Byzantine dome and mosaics. For instance, clusters of four eight-pointed stars, typical for Muslim design, are arranged on the ceiling so as to form a Christian cross.

The Monreale cathedral is generally described as "Norman-Arab-Byzantine". The outsides of the principal doorways and their pointed arches are magnificently enriched with carving and colored inlay, a curious combination of three styles—Norman-French, Byzantine and Arab.

The Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio built in 1143 by Roger II's "emir of emirs" George of Antioch was originally consecrated as a Greek Orthodox church, according to its Greek-Arab bilingual foundation charter, and was built in the Byzantine Greek cross style with some Arab influences. Another unusual church from this period is the country church of Santi Pietro e Paolo d’Agrò in Casalvecchio Siculo; it has been described "one of the most sophisticated and coherent works of architecture to emerge from the Norman rule of the island".[34]

Other examples of Arab-Norman architecture include the Palazzo dei Normanni, or Castelbuono. This style of construction persisted until the 14th and the 15th century, exemplified by the use of the cupola.[35]

Transmission to Europe[]

The points of contact between Europe and Islamic lands were multiple during the Middle Ages, with Sicily playing a key role in the transmission of knowledge to Europe, although less important than that of Spain.[36] The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in Sicily, and in Islamic Spain, particularly in Toledo (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114–1187, following the conquest of the city by the Spanish Christians in 1085). Many exchanges also occurred in the Levant due to the presence of the Crusaders there.[37]

Aftermath[]

Arabic and Greek art and science continued to be influential in Sicily during the two centuries following the Norman conquest. Norman rule formally ended in 1198 with the reign of Constance of Sicily, and was replaced by that of the Swabian Hohenstaufen Dynasty.

In 1224, however, Frederick II, responding to religious uprisings in Sicily, expelled all Muslims from the island and transferred many to Lucera over the next two decades. In the controlled environment, they could not challenge royal authority and benefited the crown in taxes and military service. Their numbers eventually reached between 15,000 and 20,000, leading Lucera to be called Lucaera Saracenorum because it represented the last stronghold of Islamic presence in Italy. The colony thrived for 75 years until it was sacked in 1300 by Christian forces under the command of Charles II of Naples. The city's Muslim inhabitants were exiled or sold into slavery,[39] with many finding asylum in Albania across the Adriatic Sea.[40] Their abandoned mosques were destroyed or converted, and churches arose upon the ruins, including the cathedral S. Maria della Vittoria.

Even under Manfred (d. 1266) Islamic influence in Sicily persisted, but it had almost disappeared by the beginning of the 14th century.[36] Latin progressively replaced Arabic and Greek, the last Sicilian document in Arabic being dated to 1245.[25]

See also[]

- Norman conquest of southern Italy

- Norman architecture

- Islam in Italy

- Italo-Norman

- History of Islam in southern Italy

- Byzantine mosaics

- Emirate of Sicily

- Hedwig glass

Notes[]

- ^ Michael Huxley: "The Geographical magazine", Vol. 34, Geographical Press, 1961, p. 339

- ^ Gordon S. Brown: "The Norman conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily", McFarland, 2003, ISBN 0786414723, p. 199

- ^ Moses I. Finley: "A History of Sicily", Chatto & Windus, 1986, ISBN 0701131551, pp. 54, 61

- ^ "In Sicily the feudal government, fastened on a country previously turbulent and backward, enabled an Arab-Norman civilization to flourish."Edwards, David Lawrence (1980). "Religion". Christian England: Its Story to the Reformation. p. 148. ISBN 9780195202298.

- ^ Koenigsberger, Helmut Georg. "The Arab-Norman civilization during the earlier Middle-Ages". The Government of Sicily Under Philip II of Spain. p. 75.

- ^ Dossiers d'Archéologie, 1997: "It is legitimate to speak about an Arab-Norman civilization until the 13th century" (Original French: "on est fondé à parler d'une civilisation arabo-normande jusqu'au XIIIeme siècle" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-03-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Abdallah Schleifer: "the monuments of a great Arab-Norman civilization" [1] Archived 2008-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lynn White, Jr.: "The Byzantinization of Sicily", The American Historical Review, Vol. 42, No. 1 (1936), pp. 1-21

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile, p. 123.

- ^ "Saracen Door and Battle of Palermo". Bestofsicily.com. 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ All the Arabic sources can be found in Michele Amari, Biblioteca arabo-sicula (Rome and Turin: 1880).

- ^ Houben, Roger II, 83.

- ^ Dalli, "Bridging Europe and Africa", 79.

- ^ Lewis, p.147

- ^ Abulafia, David (2011) The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. (London: Allen Lane). ISBN 978-0-7139-9934-1

- ^ Aubé, p.177

- ^ Aubé, p.164

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (ed.). Science in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978. p. 58-59

- ^ Aubé, p.171

- ^ Quoted in History Edition of Best of Sicily Magazine

- ^ "Normans in Sicilian History". Bestofsicily.com. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Roger II — Encyclopædia Britannica". Concise.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2007-05-23. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ Inturrisi, Louis (1987-04-26). "Tracing The Norman Rulers of Sicily". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lewis, p.148

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-521-25551-6.

ISBN 0-521-25551-1" "At the end of the twelfth century ... While in Apulia Greeks were in a majority – and indeed present in any numbers at all – only in the Salento peninsula in the extreme south, at the time of the conquest they had an overwhelming preponderance in Lucaina and central and southern Calabria, as well as comprising anything up to a third of the population of Sicily, concentrated especially in the north-east of the island, the Val Demone.

- ^ Aube, p.162

- ^ Quoted in Aubé, p.168

- ^ Quoted in Lewis, p. 148, also Aube, p.168

- ^ Aubé, p.170

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile

- ^ Aubé, pp. 164-165

- ^ "Le genie architectural des Normands a su s’adapter aux lieux en prenant ce qu’il y a de meilleur dans le savoir-faire des batisseurs arabes et byzantins", Les Normands en Sicile, p.14

- ^ Nicklies, Charles Edward (1992). The architecture of the church of SS. Pietro e Paolo d'Agro, Sicily. Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship (Thesis). University of Illinois. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile, pp. 53–57

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis, p.149

- ^ Lebedel, p.110-111

- ^ Les Normands en Sicile, p. 54.

- ^ Julie Taylor. Muslims in Medieval Italy: The Colony at Lucera Archived 2010-08-19 at Archive-It. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. 2003.

- ^ Ataullah Bogdan Kopanski. Islamization of Shqeptaret: The clash of Religions in Medieval Albania. Archived 2009-11-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Before it was finally conquered by the Muslims, this province was reorganised as the Byzantine exarchate of Africa.

References[]

- Buttitta, Antonino, ed. (2006). Les Normands en Sicile. Caen: Musée de Normandie. ISBN 8874393288.

- Amari, M. (2002). Storia dei Musulmani di Sicilia. Le Monnier.

- Aubé, Pierre (2006). Les empires normands d'Orient. Editions Perrin. ISBN 2262022976.

- Lebédel, Claude (2006). Les Croisades. Origines et conséquences. Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 2737341361.

- Lewis, Bernard (1993). Les Arabes dans l'histoire. Flammarion. ISBN 2080813625.

- Musca, Giosuè (1964). L'emirato di Bari, 847-871. Bari: Dedalo Litostampa.

- Previte-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, Julie Anne (April 2007). "Freedom and Bondage among Muslims in Southern Italy during the Thirteenth Century". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 27 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1080/13602000701308889.

- Santagati, Luigi (2012). Storia dei Bizantini di Sicilia. Lussografica.

External links[]

- Arabs in Italy

- Ethnic groups in Sicily

- Medieval Sicily

- Cultural history of Italy

- Byzantine art

- Arabic art

- Islam in Italy

- Arabic architecture

- Norman architecture in Italy

- History of religion in Italy