Biedermeier

The Biedermeier period was an era in Central Europe between 1815 and 1848 during which the middle class grew in number and the arts appealed to common sensibilities. It began with the Congress of Vienna at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and ended with the onset of the Revolutions of 1848. Although the term itself derives from a literary reference from the period, it is used mostly to denote the artistic styles that flourished in the fields of literature, music, the visual arts and interior design. It has influenced later styles, especially those originating in Vienna.[1]

Background[]

The Biedermeier period does not refer to the era as a whole, but to a particular mood and set of trends that grew out of the unique underpinnings of the time in Central Europe. There were two driving forces for the development of the period. One was the growing urbanization and industrialization leading to a new urban middle class, which created a new kind of audience for the arts. The other was the political stability prevalent under Klemens von Metternich following the end of the Napoleonic Wars[2] and the Congress of Vienna. The effect was for artists and society in general to concentrate on the domestic and (at least in public) the non-political. Writers, painters, and musicians began to stay in safer territory, and the emphasis on home life for the growing middle class meant a blossoming of furniture design and interior decorating.[3]

Literature[]

The term "Biedermeier" appeared first in literary circles in the form of a pseudonym, Gottlieb Biedermaier, used by the country doctor Adolf Kussmaul and lawyer Ludwig Eichrodt in poems that the duo had published in the Munich satirical weekly Fliegende Blätter in 1850.[4]

The verses parodied the people of the era, namely , a primary teacher and sort of amateurish poet, as depoliticized and petit-bourgeois.[5] The name was constructed from the titles of two poems—"Biedermanns Abendgemütlichkeit" (Biedermann's Evening Comfort) and "Bummelmaiers Klage" (Bummelmaier's Complaint)—which Joseph Victor von Scheffel had published in 1848 in the same magazine.[citation needed] As a label for the epoch, the term has been used since around 1900.

Due to the strict control of publication and official censorship, Biedermeier writers primarily concerned themselves with non-political subjects, like historical fiction and country life. Political discussion was usually confined to the home, in the presence of close friends.

Typical Biedermeier poets are Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich Halm, Eduard Mörike, and Wilhelm Müller, the last two of whom have well-known musical settings by Hugo Wolf and Franz Schubert respectively. Adalbert Stifter was a novelist and short story writer whose work also reflected the concerns of the Biedermeier movement, particularly with his novel, Der Nachsommer. As historian Carl Emil Schorske put it, "To illustrate and propagate his concept of Bildung, compounded of Benedictine world piety, German humanism, and Biedermeier conventionality, Stifter gave to the world his novel Der Nachsommer".[6]

Jeremias Gotthelf wrote The Black Spider (1842), an allegorical work that uses Gothic themes. It is Gotthelf's best known work. At first little noticed, the story is now considered by many critics to be among the masterworks of Biedermeier era and sensibility. Thomas Mann wrote of it in his The Genesis of Doctor Faustus that Gotthelf "often touched the Homeric" and that he admired The Black Spider "like no other piece of world literature."[7]

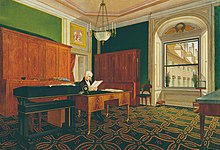

Furniture design and interior decorating[]

Biedermeier was an influential German style of furniture design that evolved from 1815–1848. The period extended into Scandinavia, as disruptions due to numerous states that made up the German nation were not unified by rule from Berlin until 1871.[clarification needed] These post-Biedermeier struggles, influenced by historicism, created their own styles. Throughout the period, emphasis was kept upon clean lines and minimal ornamentation consistent with basis of Biedermeier in utilitarian principles. As the period progressed, however, the style moved from the early rebellion against Romantic-era fussiness to increasingly ornate commissions by a rising middle class, eager to show their newfound wealth. The idea of clean lines and utilitarian postures would resurface in the 20th century, continuing into the present day. Middle to late-Biedermeier furniture design represented a heralding towards historicism and revival eras long sought for. Social forces originating in France would change the artisan-patron system that achieved this period of design, first in the German states, and then into Scandinavia. The middle class growth originated in the Industrial Revolution in Britain and many Biedermeier designs owe their simplicity to Georgian lines of the 19th century, as the proliferation of design publications reached the loose German states and Austria-Hungary.

The Biedermeier style was a simplified interpretation of the influential French Empire style of Napoleon I, which introduced the romance of ancient Roman Empire styles, adapting these to modern early 19th century households. Biedermeier furniture used locally available materials such as cherry, ash, and oak woods rather than the expensive timbers such as fully imported mahogany. Whilst this timber was available near trading ports such as Antwerp, Hamburg, and Stockholm, it was taxed heavily whenever it passed through another principality. This made mahogany very expensive to use and much local cherry and pearwood was stained to imitate the more expensive timbers. Stylistically, the furniture was simple and elegant. Its construction utilised the ideal of truth through material, something that later influenced the Bauhaus and Art Deco periods.

Many unique designs were created in Vienna, primarily because a young apprentice was examined on his use of material, construction, originality of design, and quality of cabinet work, before being admitted to the league of approved master cabinetmakers. Furniture from the earlier period (1815–1830) was the most severe and neoclassical in inspiration. It also supplied the most fantastic forms which the second half of the period (1830–1848) lacked, being influenced by the many style publications from Britain. Biedermeier furniture was the first style in the world that emanated from the growing middle class. It preceded Victoriana and influenced mainly German-speaking countries. In Sweden, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, whom Napoleon appointed as ambassador to Sweden to sideline his ambitions, abandoned his support for Napoleon in a shrewd political move. Later, after being adopted by the King of Sweden (who was childless), he became Sweden's new king as Karl XIV Johan. The Swedish Karl Johan style, similar to Biedermeier, retained its elegant and blatantly Napoleonic style throughout the 19th century.

Biedermeier furniture and lifestyle was a focus on exhibitions at the Vienna applied arts museum in 1896. The many visitors to this exhibition were so influenced by this fantasy style and its elegance that a new resurgence or revival period became popular amongst European cabinetmakers. This revival period lasted up until the Art Deco style was taken up. Biedermeier also influenced the various Bauhaus styles through their truth in material philosophy.

The original Biedermeier period changed with the political unrests of 1845–1848 (its end date). With the revolutions in European historicism, furniture of the later years of the period took on a distinct Wilhelminian or Victorian style.

The term Biedermeier is also used to refer to a style of clocks made in Vienna in the early 19th century. The clean and simple lines included a light and airy aesthetic, especially in Viennese regulators of the and Dachluhr styles.

Globe-shaped work table; 1815-1820; maple veneer, bird's eye maple, fruitwoods, gilded and ebonized wood, mirror, brass; from Vienna; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal, Canada)

Footstool; 1820-1840; carpentry embroidery upholestry; height: 29 cm, width: 46.3 cm; National Museum of Warsaw (Warsaw, Poland)

Console; 1825-1830; carpentry wood carving veneering; height: 86.6 cm, width: 104.2 cm; National Museum of Warsaw

Chess table; 1825-1835; carpentry veneering inlay; height: 77 cm; National Museum of Warsaw

Architecture[]

Biedermeier architecture was marked by simplicity and elegance, exemplified by the paintings of Jakob Alt and Carl Spitzweg. Through the unity of simplicity and functionality, the Biedermeier neoclassical architecture created tendencies of crucial influence for the Jugendstil,[8] Bauhaus, and 20th century architecture.

The Geymüllerschlössel in Vienna was constructed in 1808, it houses today the Biedermeier collection of the Museum of Applied Arts.

The Polish architectural style Świdermajer was named as a play on Biedermeier.

Visual arts[]

Austrian paintings during this era were characterized by the commitment to portray a sentimental and pious view of the world in a realistic way. Biedermeier themes reinforced feelings of security, Gemütlichkeit, traditional pieties, and simplicity, eschewing political and social commentary during the epoch.[9] Thus, the techniques, while classic in nature were of the utmost importance to reach a realistic rendering. Regarding the theme, the technique was seen not only as a narrative medium to tell the past in anecdotal vignettes, but also to represent the present. This formed an aesthetic unity most evidenced in the portraits (e.g., Portrait of the Arthaber Family, 1837, by Friedrich von Amerling), landscapes (e.g. see Waldmüller or Gauermann landscapes) and contemporary-reporting genre scenes (e.g., Controversy of the Coachmen, 1828, by Michael Neder).

Key painters of the Biedermeier movement were Carl Spitzweg (1808–1885), Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1795–1865), Henrik Weber (1818–1866), Josip Tominc (1780–1866), Friedrich von Amerling (1803–1887), Friedrich Gauermann (1807–1862), Johann Baptist Reiter (1813–1890), Peter Fendi (1796–1842), (1807–1882), Josef Danhauser (1805–1845), and Edmund Wodick (1806–1886) among others.[10]

The biggest collection of Viennese Biedermeier paintings in the world is currently hosted by the Belvedere Palace Museum in Vienna.[10]

In Denmark, the Biedermeier period corresponded with the Danish Golden Age, a time of creative production in the country which encompasses the paintings of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg and his students, including Wilhelm Bendz, Christen Købke, Martinus Rørbye, Constantin Hansen, and Wilhelm Marstrand as well as the neoclassical sculpture inspired by the example set by Bertel Thorvaldsen. The period also saw the development of Danish architecture in the Neoclassical style. Copenhagen, in particular, acquired a new look, with buildings designed by Christian Frederik Hansen and Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll.[citation needed]

Music[]

Biedermeier in music was most evident in the numerous publications for in-home music making. Published arrangements of operatic excerpts, German Lieder, and some symphonic works that could be performed at the piano without professional musical training, illustrated the broadened reach of music in this period. Composers from this period include Beethoven, Schubert, Rossini, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schumann and Liszt.

Czech lands[]

The Biedermeier period coincided with the Czech National Revival movement in the Czech-speaking areas. The most famous writers of the period were Božena Němcová, Karel Hynek Mácha, František Ladislav Čelakovský, Václav Kliment Klicpera, and Josef Kajetán Tyl. Key painters of the Czech Biedermeier were Josef Navrátil, Antonín Machek, and Antonín Mánes. Landscapes, still lifes, courtyards, family scenes, and portraits were very popular. Václav Tomášek composed lyric piano pieces and songs to the patriotic lyrics of Czech authors. Biedermeier was also reflected in the applied arts: glass and porcelain, fashion, jewellery, and furniture.

Current usage[]

Terms like Bionade-Biedermeier[11] or Generation Biedermeier have been coined to describe parallels between the historical Biedermeier and the German present. The underlying allusion is being used as well in related wordings like Bionade-Bourgeoisie. The 2010 Shell Jugendstudie used the term Generation Biedermeier for the mainstream of the younger generation in 2010. Security and private happiness then was more important than political engagement.[12]

References[]

- ^ Smith, Roberta (December 2006). "Crisp, Clean and Modern, Before Its Time". The New York Times.

- ^ Christopher John Murray, Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850, Volume 1 p. 89, Taylor & Francis, 2004.

- ^ "Biedermeier – Elegant, Simple Interior Design". Biedermeier.us. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Barea, Ilsa (1992). "III Biedermeier, pp 111-188". Vienna: legend and reality. London: Pimlico. p. 112. ISBN 0-7126-5579-4.

- ^ Ludwig Eichrodt 1827-1892 Renate Begemann Verlag der Badischen Landesbibliothek, 1992, p.115

- ^ Schorske, Carl E. (1981). Fin-De-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 283. ISBN 0-521-28516-X.

- ^ "The Black Spider". One World Classics. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Vienna: City of Modernity, 1890-1914 By Tag Gronberg. Page 124

- ^ Biedermeier-era paintings in the Belvedere, Vienna Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Biedermeier | Belvedere". Belvedere.at. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Henning Sußebach (7 November 2007). "Bionade-Biedermeier". Zeit Online. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Von Thomas Fischermann (31 August 2012). "Gibt es einen German Dream?". Zeit Online. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

Further reading[]

- Ilsa Barea (1966, republished 1992), Vienna: legend and reality, London: Pimlico. Chapter 111, Biedermeier, pp. 111-188.

- Jane K. Brown, in The Cambridge Companion to the Lied, James Parsons (ed.), 2004, Cambridge.

- Martin Swales & Erika Swales, Adalbert Stifter: A Critical Study, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

External links[]

Media related to Biedermeier at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Biedermeier at Wikimedia Commons

- Biedermeier

- Neoclassical architecture in Germany

- Neoclassical architecture in Austria

- Neoclassical architecture

- Architectural styles

- German art

- Austrian art

- Architecture of Germany

- Architecture of Austria

- German literature

- Austrian literature

- Design

- Decorative arts

- History of furniture

- German Confederation