Novgorod Land

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prehistory • Antiquity • Early Slavs

879–1240: Ancient Rus'

1240–1480: Feudal Rus'

1480–1917: Tsarist Russia

1917–1923: Russian Revolution

1923–1991: Soviet Era

since 1991: Modern Russia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Timeline 860–1721 • 1721–1796 • 1796–18551855–1892 • 1892–1917 • 1917–1927 1927–1953 • 1953–1964 • 1964–1982 1982–1991 • 1991–present |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

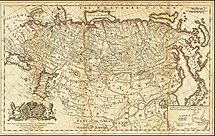

Novgorodian Land (Russian: Новгородская земля) or Novgorodchina was one of the largest historical territorial–state formations in Russia, covering its northwest and north. Novgorod Land, centered in Veliky Novgorod, was the cradle of Old Russian statehood under the rule of the Rurikovich dynasty and one of the most important princely thrones of the era of Kievan Rus'. During the collapse of Kievan Rus' and in subsequent centuries, Novgorod Land developed as an autonomous Russian state with republican forms of government under the suzerainty of the great princes of Vladimir (later – Moscow).[1][2] During the period of greatest development, it reached the North to the White Sea, and in the east it spread beyond the Ural Mountains. It had extensive trade relations within the framework of the Hanseatic League. In the 15th century, in the course of the grand–princely policy of "gathering Russian lands", Veliky Novgorod, with the surrounding lands, was completely annexed to the centralized Russian state. Novgorod Land existed as an administrative unit until 1708.

Administrative division[]

Administratively, by the end of the Middle Ages it was divided into pyatins, which, in turn, from the second half of the 16th century were divided into halves. The five–fold division was superimposed on the earlier one – on volosts, uyezds (prisuds), pogosts and stans, and, according to the annals, the foundations of this administrative division were laid in the 10th century by Princess Olga, who established places of pogosts and the size of the tribute in Novgorod Land. The Tale of Bygone Years defines it as "a great and abundant land".

Judging by the "Tale of Bygone Years" and archaeological data, by the time Rurik arrived in 862, Novgorod was already a large settlement (probably as a chain of settlements from the sources of Volkhov and Rurik Gorodishche[3][4] up to Kholopiy Town,[5] opposite of Krechevitsy), as well as Ladoga,[6] Izborsk and possibly Beloozero. The Scandinavians probably called this territory Gardariki.

After the entry of Novgorod Land into the Russian state, the territorial division was preserved, and the territories from the end of the 15th century were called pyatins, before the Novgorod Land was divided into lands, and in the 12th century into ryads – bearing the same name with pyatins – Votskaya land, Obonezhsky and Bezhetsky ryad, Shelon, Dereva. In each pyatina there were several prisuds (uyezds), in each prisud (uyezd) – several pogosts and volosts.

Some territories of relatively late Novgorod colonization were not included in the five–fold division and formed a number of volosts that were in a special position: Zavolochye or Dvinskaya land – along the Northern Dvina from Onega to Mezen. This volost was called so because it was located behind the portage – the watershed separating the Onega and Northern Dvina basins from the Volga basin and was located behind the Obonezhskaya and Bezhetskaya pyatins, where the portages to the Onega river (Poonezhie) began. Perm – in the basin of the Vychegda River and the upper Kama. Pechora – beyond the Dvina land and Perm to the north–east on both banks of the Pechora River to the Ural Range. Ugra – on the eastern side of the Ural Range.[7] Tre or Tersky Coast[8] – on the White Sea coast.

Pskov originally belonged to the Novgorod land, however its importance and autonomy grew in the late 13th and 14th centuries culminating in the recognition of the political independence of Pskov by the Treaty of Bolotovo in 1348.

The concept of "Novgorod Land" sometimes includes the area of Novgorod colonization in the Northern Dvina, in Karelia[9] and the Arctic.

Population[]

The settlement of the territory of Novgorod Land began in the Valdai Upland since the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, along the border of the Valdai (Ostashkovsky) glaciation, and in the north–west of Priilmenye, in the area of the future territorial center, since the Neolithic.

Archaeologically[10] and through the study of toponymy,[11] the presence of migratory so–called Nostratic communities is supposed here, replaced by Indo–European groups (future Balts and Slavs) who came from the south–west and ancestors of the Baltic–Finnish peoples who came from the east.[12] This multi–ethnicity is confirmed by ethnogenetics, genogeography. At the time of Herodotus, about 25 centuries ago, the lands from the Baltic to the Urals[12] were completely or partially mastered by the Androphages, Neuros, Melanchleins, Budins, Physsageti, Iirki, Northern Scythians in the Volga–Kama region, which are often localized[12] depending on the Issedones.

Under Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE, these lands were controlled[12] by the Wends, Stavs, Aors, Alans, Borussians, Tsarist Sarmatians and even more than a dozen large and small peoples. The historian Jordanes listed Eastern European peoples conquered by Ermanaric in 4th century in Getica. The list includes Vas, Merdens and Merens which are associated with Veps, Mordva and Merya/Mari respectively.[13][14][15]

In the initial part of the "Tale of Bygone Years" in the Lavrentievsky Chronicle of 1377 there is an opinion of a medieval chronicler about an older settlement of peoples:[16]

...in Afetovo, on the other hand, Rus', Chyud, and all tongues: Merya, Muroma, Ves', Mordva, Zavolochskaya Chyud, Perm, Pechera, Yam, Utra, Lithuania, Zimgol, Kors, Lytgol, Lyub, Lyakhve and Prussy and Chyuyud near the Varyazhsky sea...

It is traditionally believed that in the 6th century Krivichi tribes came here, and in the 8th century, in the process of Slavic settlement of the East European Plain, the tribe of Ilmen Slovenes came. Finnic tribes lived in the same territory, having left a memory of themselves in the names of numerous rivers and lakes. The interpretation of pre–Slavic toponymy as exclusively Finno–Ugric is questioned by some researchers.[17]

The time of Slavic settlement dates, as a rule, according to the type of kurgan groups and individual mounds located in this territory. Pskov long mounds are traditionally associated with Krivichi, and mounds in the shape of a hill with Slovenes. There is also the so–called Kurgan hypothesis, based on which various assumptions about the ways of settling this territory are possible.

Archaeological research in Staraya Ladoga[6][18] and Rurik Gorodishche[3] shows the presence of Scandinavians, traditionally referred to in the Old Russian (medieval) literary sources as Varangians, among the inhabitants of these first large settlements.

Demography[]

In addition to the Slavic population, a significant part of the Novgorod Land was inhabited[7] by various Finnic peoples.[19][20] Vodskaya pyatina along with the Slavs was inhabited by Votians and Izhora, who have long been closely associated with Novgorod. The Yem', who lived in southern Finland, was usually at enmity with the Novgorodians and more inclined to the side of the Swedes, while the neighboring Karelians usually kept to Novgorod.[7] Novgorod were often fighting Chud who inhabited Livonia and Estonia. Zavolochye was inhabited by Finnic tribes, which was often called Zavolotskaya Chud; later Novgorod colonists settled in this region.[7] Tersky coast was inhabited by the Lapps. Further, Permians and Zyryans lived in the northeast.

The center of the Slavic settlements was the vicinity of Lake Ilmen and the Volkhov River, and the Ilmen Slovenes lived here.[7]

History[]

Oldest period (before 882)[]

Novgorod Land was one of the centers of formation of the Old Russian state. It was in the Novgorod Land that the Rurikovich dynasty began to reign, and a state formation arose, which in historiography was named Novgorod Russia, Upper Russia, Povolkhov Russia, from which it is customary to begin the history of Russian statehood.

As part of Kievan Rus (882–1136)[]

At the end of the 9th – beginning of the 10th centuries (in chronicles dating to 882), the center of the Rurikovich state moved from Novgorod to Kiev. In the 10th century, Ladoga was attacked by the Norwegian jarl Eric. In 980, Novgorod Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich (the Baptist), at the head of the Varangian squad, overthrew the Kiev Prince Yaropolk. In the 990s, Novgorod refused to convert to Christianity, and stood up for its faith with the supreme priest Bogumil Solovey and tysyatsky Ugonyay. Novgorod was baptized by force with "fire and sword": many Novgorodians were killed, and the whole city burned down. In 1015–1019, Prince of Novgorod Yaroslav Vladimirovich the Wise overthrew the Kiev Prince Svyatopolk the Accursed. The Novgorodians supported Yaroslav during the war, and after his victory in the war, Yaroslav rewarded them and granted the "Yaroslav's Law" and the "Charter" to Novgorod. These documents became the prototype of and were referenced in the charters on which the princes invited by Novgorodians took the oath. Also under Yaroslav, Detinets and the first Saint Sophia Cathedral were built.[21][22]

In 1032, in a campaign on the Iron Gate, the Novgorodians were headed by the governor Uleb.[23] In 1020 and 1067, Novgorod Land was attacked by the Polotsk Izyaslavichs.

In the 11th century, the governor – the son of the Kiev prince – still had great powers. In the same period, the institute of posadniks appeared, who ruled in Novgorod at a time when its prince was not there (like Ostromir) or the prince was a minor, as in 1088, when Vsevolod Yaroslavich sent his grandson Mstislav (son of Vladimir Monomakh) to reign in Novgorod. In 1095, the Novgorodians, dissatisfied with the absence of their prince Davyd Svyatoslavich, returned Mstislav, and seven years later they opposed the attempt of the Kiev prince to replace Mstislav with his son. The key republican authorities (veche, prince, posadnik) emerged in Novgorod in the 11th century.[21][22]

In the second decade of the 12th century, Vladimir Monomakh strengthened the central authority in Novgorod Land. In 1117, without taking into account the opinion of the Novgorod community, Mstislav was recalled to the south by his father, and Prince Vsevolod Mstislavich was seated on the throne of Novgorod. Some boyars opposed this decision of the prince, in connection with which they were called to Kiev and thrown into prison.

After the death of Mstislav the Great in 1132 and the deepening tendencies of political fragmentation, the prince of Novgorod lost the support of the central government. In 1134, Vsevolod was expelled from the city. Returning to Novgorod, he was forced to conclude a "row" with the Novgorodians, limiting his authority. On January 26, 1135, the army of Novgorod, led by Vsevolod and Izyaslav Mstislavich, lost the Battle of Zhdanaya Mountain to the army of Suzdal Prince Yuri Dolgorukiy. On May 28, 1136, in connection with the dissatisfaction of Novgorod with the actions of Prince Vsevolod, he was taken into custody, and then expelled from Novgorod.

Republican period (1136–1478)[]

Vladimir–Suzdal influence[]

In 1136, after the expulsion of Vsevolod Mstislavich, republican rule was established on Novgorod Land. Svyatoslav Olgovich, the younger brother of Vsevolod of Chernigov, the main ally of the Mstislavichs and rival of the then Kiev prince, Yaropolk from the House of Monomakh, became the first prince independently called upon by the Novgorodians. As a rule, a representative of one of the two warring princely groups was invited to Novgorod either immediately after his allies occupied key positions in Southern Russia, or before that. Sometimes the Novgorodians helped their allies to take these positions, as, for example, in 1212.

The greatest threat to Novgorod independence was posed by the princes of Vladimir (who achieved the strengthening of personal power in their principality after the defeat of the old Rostov–Suzdal boyars in 1174–1175), since they had an effective lever of influence on Novgorod. They captured Torzhok several times and blocked the supply of food from their "lower" lands.

The Novgorodians also made campaigns in North–Eastern Russia, in particular, under the leadership of Vsevolod Mstislavich, they fought at Zhdanaya Mountain on January 26, 1135, and in 1149, together with Svyatopolk Mstislavich, ravaged the surroundings of Yaroslavl and left because of the spring flood, also as part of the struggle against Yuri Dolgoruky.

In 1170, immediately after the capture of Kiev by the troops of Andrei Bogolyubsky and his allies, the Suzdalites undertook a campaign against Novgorod, in which Roman Mstislavich, the son of the prince expelled from Kiev, was located. The Novgorodians managed to win the defensive battle and defend their independence with the enemy suffering heavy losses.

From 1181 to 1209, with intervals of 1184–1187 and 1196–1197, the Vladimir–Suzdal dynasty was in power in Novgorod, from 1197 its rule was continuous.[24]

Victories of Mstislav Udatny[]

In the early spring of 1209, the Toropets prince Mstislav Mstislavich Udatny took Torzhok, capturing not only the local posadnik and several merchants, but also a group of noblemen of the Novgorod prince Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich, the youngest son of Vladimir prince Vsevolod the Big Nest. After that, he sent a letter to Novgorod with the offer of help:

"I bow to Saint Sophia, and the tomb of my father, and all Novgorodians; I have come to you having heard about the violence from the prince, and I pity my patrimony."

Having learned about the capture of Torzhok, Vsevolod the Big Nest sent his eldest son Constantine against him. However, apparently Mstislav had the support within the city as Novgorodians arrested their current prince Svyatoslav (brother of Constantine) and expressed support for the new chosen one, confirming the right to "liberty in the princes." In this way, the safety of Mstislav was guaranteed, after which Constantine was forced to stop in Tver and his father who avoided military conflicts in his old age recognized Mstislav as the legitimate ruler of Novgorod.

When he came to Novgorod Mstislav did not have influential patrons or great wealth but he had proved himself as a capable military commander. The Novgorod Chronicle speaks of him in an extremely positive way: fair in court and punishment, a successful commander, attentive to the concerns of people, and noble and selfless.

In Novgorod, Mstislav showed decisiveness and initiative in internal affairs: he replaced the posadniks and the archbishop, launched active construction in the city and the posad, undertook the reconstruction of defensive structures on the southern approaches to his land: the fortress walls of Velikiye Luki were reconstructed and the town was placed under control of Mstislav's brother Vladimir who resided in Pskov.

After that, Pskov became responsible for the southern (Polotsk, Lithuania) and western (Estonia, Latgale) borders of Novgorod Land and also controlled the border regions of Southern Estonia (Ugandi, Waiga and partly Sakala) and Northern Latgale (Talava, Ochela). The lands of Northern Estonia (Vironia), Vody, Izhora and Karelia remained under the influence of Novgorod.

Thus, the administrative–political, defensive, and commercial significance of Pskov began to grow in the process of transforming the Baltic states from a backward pagan province into an important region foe the Western European trade, church, and military expansion. This led to the nomination of a separate prince for Pskov during the reign of Mstislav in Novgorod.[24] He also led a new wave of Russian resistance to the crusaders in the Baltic states.

Mstislav's father Mstislav the Brave, who reigned in Novgorod for less than a year and was buried in Saint Sophia Cathedral (1180), was remembered for his victorious campaign against the Chud at the head of 20,000 troops in 1179. Therefore, Mstislav Udatny began his military campaigns with a similar operation.

At the end of 1209, he made a brief raid into Estonian Vironia, returning with rich booty, and in 1210 made a large campaign against the Chud, capturing the Bear's Head. He took from the Estonians not only a tribute, but also a promise to be baptized into Orthodoxy. He first used Christianity as an additional measure to strengthen his power, which previously had been done only by the Catholics. However, the Orthodox priests were not as mobile as the Catholic ones, and the prince's initiative was not continued: instead priests from Riga came to the Estonians and thus the Bear's Head (Odenpe) later became one of the lands of the Riga bishopric.

Dissatisfied with the passivity of the church Mstislav achieved the removal from service of Archbishop Mitrofan in January 1211 and proposed to nominate Dobrynya Yadreikovich, a monk of the Khutynsky monastery and a member of an influential boyar clan. He became an archbishop under the name of Anthony and was an ardent supporter of preaching and missionary work on the Russian frontiers.[24]

By 1210 the Germans started the conquest of Estonians and signed a peace treaty with Polotsk promising to pay the "Livonian" tribute. The relations between Albert and Pskov - and by extension Novgorod - were strengthened by the marriage of the daughter of Pskov Prince Vladimir Mstislavich (Mstislav's brother) and Theodoricus, the younger brother of Bishop Albert. According to some historians the collaboration between Albert and Vladimir was tantamount to dividing Estonia between them.[25]

At the same time, recognizing the rights of Riga to the lands along the Daugava (possibly also Kukenois and Gerzike) improved the position of Novgorod and Pskov at the expense of Prince of Polotsk Vladimir who lost the support of his compatriots.[24]

Between Moscow, Lithuania and Livonian Order[]

In 1216, when the brother of Vladimir Prince Yaroslav organized an economic blockade of Novgorod, Novgorodians, with the help of Smolensk princes, intervened in the power struggle between the Suzdal princes, as a result of which the Vladimir prince was overthrown. However, at the beginning of the 13th century, German Catholic orders (the Order of the Swordsmen and the Teutonic Order) completed the subordination of the Baltic tribes, who had previously paid tribute to Novgorod and Polotsk, and reached the borders of the Russian lands themselves which set the stage for the conflict between Novgorod and the crusader orders in the first half of 13th century. Pskov and Novgorod for a successful fight against them began to need an ally, ready to provide military assistance if necessary. But help did not always come on time, both because of the remoteness of Vladimir from the northwestern borders of Russia, and because of disagreements between the Novgorod nobility and the princes of Vladimir. The more dangerous position of Pskov gave rise to disagreements between Pskov and Novgorod. The Pskovites demanded from Novgorodians and Vladimirites either decisive successes in the Baltic campaigns, or peace with the Order. Pskov often received princes expelled by the Novgorodians.

During the Mongol invasion of Russia the southern parts of Novgorod land were devastated; Volok Lamsky, Vologda, Bezhetsk, Torzhok were all captured by the invaders. Several versions have been proposed by historians to explain the Mongols' refusal to march on Novgorod after the capture of Torzhok on March 5: the upcoming spring thaw, lack of fodder and high losses in the struggle against the Ryazan and Vladimir principalities.[26][27] On July 15, 1240, Alexander Yaroslavich defeated the Swedes on the Neva and on April 5, 1242 he won the Battle on the Ice of the lake Peipus against the Livonian Order. In 1257–1259 he established his influence in Novgorod threatening it with a Mongol pogrom. In 1268, the Livonian order was again defeated in the fierce Battle of Rakovor.

In the beginning of the 14th century, princes of Tver and Moscow princes vied for the influence over Novgorod. The Golden Horde supported Moscow in this struggle trying to prevent a noticeable advantage of one Russian prince over another and the Novgorod nobility sympathized with the Moscow princes as Moscow was farther than Tver and was thought to pose less danger. Thus the attempt of Mikhail of Tver to subjugate Novgorod by force was thwarted. The independence of Pskov was recognised by Novgorod in 1348 by the Treaty of Bolotovo. According to some primary sources, the Novgorodians participated in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, however some historians question these accounts.[28]

In 1326, in Novgorod, Bishop Moses, Posadnik Olfromey and Tysyatsky Ostafy signed a treaty with the ambassador of the King of Sweden and Norway Magnus IV which defined the spheres of influence in Lappland. Rather than setting a fixed border the treaty stipulated which part of the aboriginal Sami people would pay tribute to Norway and which to Novgorod.[29]

Novgorod traded with Baltic cities for the most part of its history with the first known treaty with Gotland and German cities dating to the late 12th century. After the Baltic cities formed the Hansa a conflict between Novgorod and Hansa ensued. Novgorodians complained about the terms of the fur and salt trade and both sides arrested merchants and confiscated the goods belonging to the other side. The treaty of 1392, known as Niebur's Peace, resolved most of the issues and became the basis for the relationship between Novgorod and Hansa, in spite of several conflicts occurring in the 15th century.[30][31] The trade with Livonian cities was disrupted by the wars between Novgorod and the Livonian Order. The latter forbade selling horses to Novgorod in 1439 and 1440 and between 1443 and 1450 the Hansa kontor was closed. The importance of trade with the Hansa diminished during the 15th century while the trade with Narva, Stockholm and Vyborg was growing.[31]

The stone walls of the Kremlin and numerous new churches were constructed in 14th century which is considered the golden age of Novgorod architecture. While chronicle-writing existed in Novgorod from the times of Kievan Rus, new genres of literature such as travelogues, novels and hagiographies appeared in 14-15th centuries. Novgorod started minting its own novgorodka coins in 1420[32] and in 1440 a Judicial Charter was issued which codified legal practices.

After 1330s Grand Duchies of Moscow and Lithuania started to dominate the Russian lands and subsequently Novgorodians invited princes from both grand duchies. In 1449 Moscow concluded an Eternal Peace agreement with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania delimiting zones of influence in Russia. In the next few years Vasily the Blind defeated his rival Dmitry Shemyaka and prevailed in the Muscovite Civil War. Dmitry Shemyaka died (possibly by poisoning) in Novgorod in 1453. Vasily the Blind attacked Novgorod in 1456 and after the Novgorodians' defeat in the battle of Staraya Russa they were forced to conclude the Treaty of Yazhelbitsy with Moscow, according to which the powers of the Moscow prince in Novgorod affairs were significantly expanded.

Novgorod signed a treaty with Casimir IV of Poland-Lithuania and invited him to rule as a prince. The treaty safeguarded the Orthodox church in Novgorod: the posadnik was to be Orthodox and the king was not allowed to build Catholic churches in the Novgorod Land. In spite of this, Ivan III launched his first campaign against Novgorod in 1471 alleging that they converted to Catholicism. After the Novgorodian army was defeated in the Battle of Shelon and the city was besieged, the peace treaty of Korostyn was signed according to which Novgorod acknowledged it as a patrimony of Ivan III, subjected its foreign policy to Moscow, accepted the Grand Prince as the ultimate judicial authority and lost some peripheral lands to the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The Novgorod Land was annexed completely in 1478 and the veche bell was removed to Moscow.[33]

As part of a centralized Russian state (from 1478)[]

Having conquered Novgorod in 1478, Moscow inherited its former political relations with its neighbors. The legacy of the independence period was the preservation of diplomatic practice, in which the northwestern neighbors of Novgorod – Sweden and Livonia – maintained diplomatic relations with Moscow through the Novgorod governors of the Grand Duke.

In territorial terms, Novgorod Land in the era of the Tsardom of Russia (16th–17th centuries) was divided into 5 fifths (pyatinas): Vodskaya, Shelonskaya, Obonezhskaya, Derevskaya and Bezhetskaya. The smallest units of the administrative division at that time were pogosts.

The lands confiscated from the previous owners were either declared state lands or given to Muscovite military servicemen as manors. The burden on peasants living on state lands significantly decreased compared to the republican period as the in-kind rents were replaced by money ones. On the other hand the rents paid by peasants living on servicemen's manors changed little and sometimes even increased. Two censuses were carried out in the Novgorod land in the end of 15th century after the incorporation of Novgorod Land into Muscovy which are the earliest surviving records of the population of Russia. The population increased by 14% between the two censuses.[34]

On March 21, 1499, the son of Tsar Ivan III Vasily was declared Grand Prince of Novgorod and Pskov. In April 1502 he was proclaimed the Grand Duke of Moscow and Vladimir and the autocrat of All Russia and thus became the co–ruler of Ivan III. After the death of Ivan III on October 27, 1505 he became the sole monarch of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Reign of Ivan the Terrible[]

In 1565, after Tsar Ivan the Terrible divided the Russian State into oprichnina and zemshchina, the city became part of the latter.[35][36] Huge damage to Novgorod was caused by the oprichnina pogrom, which was perpetrated in the winter of 1569/1570 by an army personally led by Ivan the Terrible. The reason for the pogrom was the denunciation and suspicions of treason (as modern historians suggest, the Novgorod conspiracy was invented by the favorites of Ivan the Terrible, Vasily Gryazny and Malyuta Skuratov). All cities on the road from Moscow to Novgorod were looted and Malyuta Skuratov personally strangled Metropolitan Philip in the Tver. The number of victims in Novgorod is estimated between 3,000 and 27,000, out of the total population of 35 thousand people. The pogrom lasted for six weeks and thousands of people were tortured and drowned in Volkhov. The city was plundered and the property of churches, monasteries and merchants was confiscated.

The population of Novgorod land at the turn of 16th century was estimated to be from 500 to 800 thousand and it was largely stable or slightly increased in the first half of the century. According to Turchin and Nefedov, Novgorod Land experienced overpopulation during this period leading to inferior soils brought into cultivation, increasing use of fertilisers, epidemics and declining per capita consumption. As a result of a severe epidemic hitting Novgorod in 1552, massacres by Ivan the Terrible, repeated crop failures and the increasing tax burden, the population decreased five times by the end of the century.[37][38]

Time of Troubles. Swedish occupation[]

In 1609 the government of Vasily Shuisky concluded the Vyborg Treaty with Sweden, according to which Korela was transferred to the Swedish crown in exchange for military assistance.

Ivan Odoevsky was appointed governor of Novgorod in 1610. In the Tsar Vasily Shuisky was overthrown and Moscow swore allegiance to Prince Vladislav. In Moscow, a new government was formed, which began to swear royal and other cities of the Russian state. Ivan Saltykov was sent to Novgorod to be sworn in and to guard against the Swedes who had appeared in the north and from thieves' gangs at that time. The Novgorodians, and probably led by Odoevsky, who was constantly in good relations with the Metropolitan Isidor of Novgorod, who had a great influence on the Novgorodians, and, apparently, who had respect and love among the Novgorodians, agreed not earlier to let Saltykov in and swear allegiance to the prince until they will receive from Moscow a list of approved crucifix letters; but they received an oath only after they took a promise from Saltykov that he would not bring the Poles with him to the city.

Soon in Moscow and throughout Russia a strong movement arose against the Poles; at the head of the militia, which set out to expel the Poles from Russia, became Prokopy Lyapunov, together with some other persons, formed the provisional government, which, having entered into government of the country, began sending out and the governor in the cities.

In the summer of 1611, Swedish general Jacob De la Gardie with his army approached Novgorod. He entered into negotiations with the Novgorod authorities. He asked the governor whether they are enemies to the Swedes or friends and whether they want to comply with the Vyborg treaty concluded with Sweden under Tsar Vasily Shuisky. The governors could only answer that it depends on the future king and that they have no right to answer this question.

The Lyapunov government sent the governor Vasily Buturlin to Novgorod. Buturlin, arriving in Novgorod, began to behave differently: immediately began negotiations with De la Gardie, offering the Russian crown to one of the sons of King Charles IX. Negotiations began that dragged on, but meanwhile, Buturlin and Odoevsky got into a feud: Buturlin did not allow cautious Odoevsky to take measures to protect the city. Buturlin allowed De la Gardie to cross the Volkhov and approach the suburban Kolmovsky monastery under the pretext of negotiations, and even allowed Novgorod merchants to supply the Swedes with supplies.

The Swedes realized that it seemed to them a very convenient opportunity to seize Novgorod, and on July 8 they had an attack that was only repealed because the Novgorodians had time to burn the posads surrounding Novgorod. However, the Novgorodians did not last long in the siege: on the night of July 16, the Swedes managed to break into Novgorod. The resistance was weak, since all the military men were under the command of Buturlin, who retired from the city after a short battle and having robbing Novgorod merchants. Odoevsky and Metropolitan Isidore locked themselves in the Kremlin but with no military supplies or men at their disposal they had to enter into negotiations with De la Gardie. An agreement was concluded under which Novgorodians recognized the Swedish king as their patron, and De la Gardie was admitted to the Kremlin.

By the middle of 1612 the Swedes occupied all of Novgorod Land, except for Pskov and Gdov. After an unsuccessful attempt to take Pskov the Swedes ceased hostilities.

Prince Pozharsky did not have enough troops to fight simultaneously with the Poles and Swedes, so he began negotiations with the latter. In May 1612 Stepan Tatishchev, the ambassador of the Zemstvo government, was sent from Yaroslavl to Novgorod with letters to Metropolitan Isidor of Novgorod, Prince Ivan Odoyevsky, and Jacob De la Gardie, Commander of the Swedish Forces. The government asked Metropolitan Isidor and Boyar Odoevsky how they were doing with the Swedes? The government wrote to De la Gardie that if the king of Sweden gives his brother to the state and christens him in the Orthodox Christian faith, then they are glad to be on the same council with the Novgorodians. Odoevsky and De la Gardie replied that they would soon send their ambassadors to Yaroslavl. Returning to Yaroslavl, Tatishchev announced that there was nothing to be expected from the Swedes. Negotiations with the Swedes about Karl–Philippe's candidate for Moscow's kings became a reason for Pozharsky and Minin to convene the Zemsky Cathedral.[39] In July, the promised ambassadors arrived in Yaroslavl: hegumen of the Vyazhitsky monastery Gennady, Prince Fyodor Obolensky, and out of all the pyatins, from the noblemen and from the townspeople – by person. On July 26, Novgorodians appeared before Pozharsky and stated that "the prince is now on the road and will soon be in Novgorod". The ambassadors' speech ended with the sentence "to be with us in love and unity under the hand of one sovereign."

Then from Yaroslavl to Novgorod a new embassy of Perfiliy Sekerin was sent. He was instructed, with the assistance of Novgorod Metropolitan Isidor, to conclude an agreement with the Swedes "so that the peasantry would be quiet and at peace." It is possible that in connection with this, the question of the election of the king of the Swedish royal, recognized by Novgorod, was raised in Yaroslavl. However, the royal election in Yaroslavl did not take place.

In October 1612, Moscow was liberated and it became necessary to choose a new sovereign. From Moscow to many cities of Russia, including Novgorod, letters were sent on behalf of the liberators of Moscow – Pozharsky and Trubetskoy. In the beginning of 1613 Zemsky Sobor was held in Moscow, at which a new Tsar, Mikhail Romanov, was elected.

On May 25, 1613, an uprising began against the Swedish garrison in Tikhvin. The rebellious posad people recaptured the fortifications of the Tikhvin Monastery from the Swedes and withstood the siege in them until mid–September, forcing the De la Gardie troops to retreat. With a successful Tikhvin uprising, the struggle for the liberation of Northwest Russia and Novgorod begins, culminating in the signing of the Stolbovsky Peace Treaty in 1617.

The Swedes left Novgorod only in 1617. Only a few hundred inhabitants remained in a completely ruined city. The borders of Novgorod Land were significantly reduced due to the loss of lands bordering Sweden on the Treaty of Stolbovo of 1617.

17th-18th centuries[]

Novgorod recovered from the destruction during the Time of Troubles and remained an important city in the rest of 17th century. The trade with Sweden continued to be carried out by Novgorod merchants and a Swedish trading post was opened in the city in 1627. Novgorod was one of the major centres of crafts of the Russia, with more than 200 distinct professions and a wide range of goods produced in the city. The walls and ramparts were restored and many new buildings were constructed in Novgorod, including the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign, the stone bridge over Volkhov, trade rows and Voivode's court.[40] Elsewhere, the Resurrection Cathedral was built in Staraya Russa.

The Novgorod Land became one of the Old Believers' strongholds after the Schism.[41]

The importance of Novgorod decreased after the coast of Baltic Sea was reconquered by Peter I from Sweden and the new capital was founded there. In 1708, the Novgorod land became part of the Ingermanland (from 1710 – Saint Petersburg Governorate) and Arkhangelogorod Governorates, and in 1726 the Novgorod Governorate was created, in which there were 5 provinces: Novgorod, Pskov, Tver, Belozerskaya and Velikolutskaya.

References[]

- ^ Anton Gorsky. Russian Lands in the 13th–14th Centuries: the Path of Political Development – Saint Petersburg: Nauka, 2016 – Pages 63–67

- ^ Alexander Filyushkin. Titles of Russian Sovereigns – Moscow; Saint Petersburg: Alliance Archeo, 2006 – Pages 39–40

- ^ a b Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Rurikovo Settlement

- ^ Evgeny Nosov. Typology of the Volga Region Cities. "Novgorod and Novgorod Land. History and Archeology". Materials of the Scientific Conference

- ^ Evgeny Nosov, Alexey Plohov. Kholopiy Gorodok. Antiquities of the Volga Region – Pages 129–152

- ^ a b Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Staraya Ladoga Articles about Novgorod

- ^ a b c d e Novgorod the Great // Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: in 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional) – Saint Petersburg, 1890–1907

- ^ Vasily Klyuchevsky. "The Course of Russian History": Essays in 9 Volumes. Volume 1. Lecture 23 See Vasily Klyuchevsky

- ^ Saksa Alexander Ivanovich, the Dissertation

- ^ Maya Zimina. Neolithic Basin of the Msta River. Moscow: Nauka, 1981. 205 Pages, 22 Illustrations

- ^ Ruth Ageeva. Hydronymy of the Russian North–West as a Source of Cultural and Historical Information. URSS Editorial, 2004

- ^ a b c d Vladimir Petrukhin, Dmitry Raevsky. Essays on the History of the Peoples of Russia in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Tutorial. Series: Studia Historica. 2nd Edition, Revised and Supplemented. Moscow: Znak, 2004 – 416 Pages George Vernadsky. Ancient Russia. Tver – Moscow: Lean; Agraf, 1996. (2000) – 447 Pages

- ^ Helfen, Otto (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780520015968.

- ^ Green, D. H. (2000). Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780521794237.

- ^ "List of the Peoples of Germanaric" – Gothic Way from Ladoga to Kuban

- ^ Laurentian Chronicle. (Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles. Volume One). Leningrad, 1926–1928

- ^ Valery Vasiliev. Ancient European Hydronymy in Priilmenye // Bulletin of Novgorod State University. 2002. No. 21

- ^ Tatyana Jackson. Aldeiguborg: Archeology and Toponymy

- ^ Alexander Saks. Novgorod, Karelia and Izhora Land in the Middle Ages // The Past of Novgorod and Novgorod Land. Velikiy Novgorod. 2005

- ^ Alexander Saks. The Medieval Korela. Formation of Ethnic and Cultural Community

- ^ a b Igor Yakovlevich Froyanov (1992). Rebellious Novgorod. Essays on the History of Statehood, Social and Political Struggle of the Late 9th – Early 13th Centuries. Publishing House of Saint Petersburg University.

- ^ a b Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov (1994). Russian Republic. Charley. ISBN 5-86859-020-1.

- ^ Alexey Gippius. Scandinavian Footprint in the History of the Novgorod Nobility // Slavica Helsingiensia 27, 2006 – Pages 93–108

- ^ a b c d Khrustalyov Denis Grigorievich (2018). "Novgorod and its Power in the Baltic States in the 12th – First Quarter of the 13th Century". Northern Crusaders. Russia in the Struggle for Spheres of Influence in the Eastern Baltic of the 12th–13th Centuries (3rd ed.). Saint Petersburg: Eurasia. Scientific Editor Trofimov. pp. 68–138. ISBN 978-5-91852-183-0.

- ^ Selart, Anti (2015). Livonia, Rus’ and the Baltic Crusades in the Thirteenth Century. Brill. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9789004284753.

- ^ Каргалов В. В. (2008). Русь и кочевники. Вече. p. 66. ISBN 978-5-9533-2921-7.

- ^ Vladimir Yanin (2013). Очерки истории средневекового Новгорода (in Russian). Изд-во «Русскій Міръ»; ИПЦ «Жизнь и мысль». pp. 117–130. ISBN 978-5-8455-0176-9.

- ^ Каргалов В. В. (1984). Конец ордынского ига (in Russian). Наука. p. 45.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric (1997). "The making of a Russo-Swedish frontier, 1295-1326". The Northern Crusades. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780140266535.

- ^ Igor Lagunin. Izborsk and the Hansa. Niebur's Peace. 1391

- ^ a b Рыбина Е. А. (2009). "Новгород и Ганза в XIV—XV вв.". Новгород и Ганза. Рукописные памятники Древней Руси.

- ^ Зварич В.В., ed. (1980). "Новгородская денга, новгородка". Нумизматический словарь. Львов: Высшая школа.

- ^ В. Л. Янин (2013). "Падение Новгорода". Очерки истории средневекового Новгорода (in Russian). Изд-во «Русскій Міръ»; ИПЦ «Жизнь и мысль». pp. 322, 323, 327. ISBN 978-5-8455-0176-9.

- ^ Шапиро, Александр Львович. Аграрная история Северо-Запада России: Вторая половина XV-начало XVI в (in Russian). 1971: Наука. pp. 48–50, 173, 373.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) (cited via Turchin, Peter; Nefedov, Sergey (2009). Secular cycles. Princeton University Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-691-13696-7.) - ^ Vasily Storozhev. Zemshchina // Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: in 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional) – Saint Petersburg, 1890–1907

- ^ Zemshchina // Great Russian Encyclopedia: in 35 Volumes / Editor–in–Chief Yuri Osipov – Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia, 2004–2017

- ^ Горская, Наталья Александровна (1994). Историческая демография России эпохи феодализма: итоги и проблемы изучения (in Russian). Москва: Наука. pp. 94–97. ISBN 9785020097506.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Nefedov, Sergey (2009). Secular cycles. Princeton University Press. pp. 244–245, 251–252. ISBN 978-0-691-13696-7.)

- ^ "Hidden Facts from the History of the Romanov Dynasty". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in Russian). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Kovalenko, Guennadi (2010). Великий Новгород. Взгляд из Европы XV-XIX centuries (in Russian). Европейский Дом. pp. 48, 72, 73. ISBN 9785801502373.

Sources[]

- Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles. Onomastics on Novgorod in Signs / Vladimir Burov. The Ancient Settlement of Varvarina Gora. Settlement of 1st–5th and 11th–14th Centuries in the South of Novgorod Land. Publisher: Nauka, 2003 – 488 Pages

- Victor Bernadsky. Novgorod and Novgorod Land in the 15th Century. Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union, 1961 – 399 Pages

- Valery Vasiliev (2005). Archaic Toponymy of Novgorod Land (Old Slavic Deanthroponyms) ((Series "Monographs"; Issue 4) ed.). Velikiy Novgorod: Novgorod State University Named after Yaroslav the Wise. p. 468. ISBN 5-98769-006-4. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25.

- Alice Gordienko. The Cult of Holy Healers in Novgorod in the 11–12th Centuries // Ancient Russia. Questions of Medieval Studies. 2010. N1 (39). Pages 16–25

- Igor Froyanov. Ancient Russia of the 9th–13th Centuries. Popular Movements. Princely and Veche Power. Moscow: Russian Publishing Center, 2012

- Konstantin Nevolin. About Pyatinas and Pogosts of Novgorod in the 16th Century, with the Application of the Map. Saint Petersburg: Printing House of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1853

- Professor Vasily Klyuchevsky. "A Brief Guide on Russian History. Novgorod Land"

External links[]

- Novgorod Land in the 12th–Early 13th Centuries // Site of Natalia Gavrilova

- Russian Principalities in the 1st Half of the 14th Century. Map from the Portal "New Herodotus"

- Historical regions in Russia

- Novgorod Republic