Periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of (the) elements, is a tabular display of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of chemistry. It is a graphic formulation of the periodic law, which states that the properties of the chemical elements exhibit a periodic dependence on their atomic numbers.

The table is divided into four roughly rectangular areas called blocks. The rows of the table are called periods, and the columns are called groups. Elements from the same column group of the periodic table show similar chemical characteristics. Trends run through the periodic table, with nonmetallic character (keeping their own electrons) increasing from left to right across a period, and from down to up across a group, and metallic character (surrendering electrons to other atoms) increasing in the opposite direction. The underlying reason for these trends is electron configurations of atoms.

The first periodic table to become generally accepted was that of the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869: he formulated the periodic law as a dependence of chemical properties on atomic mass. Because not all elements were then known, there were gaps in his periodic table, and Mendeleev successfully used the periodic law to predict properties of some of the missing elements. The periodic law was recognized as a fundamental discovery in the late 19th century, and it was explained with the discovery of the atomic number and pioneering work in quantum mechanics of the early 20th century that illuminated the internal structure of the atom. With Glenn T. Seaborg's 1945 discovery that the actinides were in fact f-block rather than d-block elements, a recognisably modern form of the table was reached. The periodic table and law are now a central and indispensable part of modern chemistry.

The periodic table continues to evolve with the progress of science. In nature, only elements up to atomic number 94 exist; to go further, it was necessary to synthesise new elements in the laboratory. Today, all the first 118 elements are known, completing the first seven rows of the table, but chemical characterisation is still needed for the heaviest elements to confirm that their properties match their positions. It is not yet known how far the table will stretch beyond and whether the patterns of the known part of the table will continue into this unknown region. Some scientific discussion also continues regarding whether some elements are correctly positioned in today's table. Many alternative representations of the periodic law exist, and there is some discussion as to whether or not there is an optimal form of the periodic table.

| Part of a series on the |

| Periodic table |

|---|

|

Elements |

|

Overview

The smallest constituents of all normal matter are known as atoms. Atoms are extremely small, being about one ten-billionth of a meter across; thus their internal structure is governed by quantum mechanics.[1] Atoms consist of a small positively charged nucleus, made of positively charged protons and uncharged neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons; the charges cancel out, so atoms are neutral.[2] Electrons participate in chemical reactions, but the nucleus does not.[2] When atoms participate in chemical reactions, they may gain or lose electrons to form positively- or negatively-charged ions; or they may share electrons with each other instead.[3]

Atoms can be subdivided into different types based on the number of protons (and thus also electrons) they have.[2] This is called the atomic number, often symbolised Z[4] as German for number is Zahl. Each distinct atomic number therefore corresponds to a class of atom: these classes are called the chemical elements.[5] The chemical elements are what the periodic table classifies and organises. Hydrogen is the element with atomic number 1; helium, atomic number 2; lithium, atomic number 3; and so on. Each of these names can be further abbreviated by a one- or two-letter chemical symbol; those for hydrogen, helium, and lithium are respectively H, He, and Li.[6] Neutrons do not affect the atom's chemical identity, but do affect its weight. Atoms with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons are called isotopes of the same chemical element.[6] Naturally occurring elements usually occur as mixes of different isotopes; since each isotope usually occurs with a characteristic abundance, naturally occurring elements have well-defined atomic weights, defined as the average mass of a naturally occurring atom of that element.[7]

Today, 118 elements are known, the first 94 of which occur in nature. Of the 94 natural elements, eighty are stable; three more (bismuth, thorium, and uranium) undergo radioactive decay, but so slowly that large quantities survive from the formation of the Earth; and eleven more decay quickly enough that their continued trace occurrence rests on being constantly regenerated as intermediate products of the decay of thorium and uranium. All 24 known artificial elements are radioactive.[6]

The periodic table is a graphic description of the periodic law,[8] which states that the properties and atomic structures of the chemical elements are a periodic function of their atomic number.[9] Elements are placed in the periodic table by their electron configurations,[10] which exhibit periodic recurrences that explain the trends of properties across the periodic table.[11]

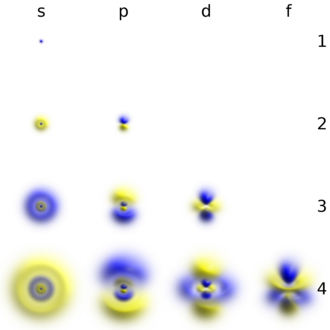

An electron can be thought of as inhabiting an atomic orbital, which characterises the probability it can be found in any particular region of the atom. Their energies are quantised, which is to say that they can only take discrete values. Furthermore, electrons obey the Pauli exclusion principle: different electrons must always be in different states. This allows classification of the possible states an electron can take in various energy levels known as shells, divided into individual subshells, which each contain a certain kind of orbital. Each orbital can contain up to two electrons: they are distinguished by a quantity known as spin, which can be up or down.[12][a] Electrons arrange themselves in the atom in such a way that the total energy they have is minimised, so they occupy the lowest-energy orbitals available unless energy has been supplied.[14] Only the outermost electrons (so-called valence electrons) have enough energy to break free of the nucleus and participate in chemical reactions with other atoms. The others are called core electrons.[15]

| ℓ → n ↓ |

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital | s | p | d | f | g | h | i | Capacity of shell |

| 1 | 1s | 2 | ||||||

| 2 | 2s | 2p | 8 | |||||

| 3 | 3s | 3p | 3d | 18 | ||||

| 4 | 4s | 4p | 4d | 4f | 32 | |||

| 5 | 5s | 5p | 5d | 5f | 5g | 50 | ||

| 6 | 6s | 6p | 6d | 6f | 6g | 6h | 72 | |

| 7 | 7s | 7p | 7d | 7f | 7g | 7h | 7i | 98 |

| Capacity of subshell | 2 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 18 | 22 | 26 |

Elements are known with up to the first seven shells occupied. The first shell contains only one orbital, a spherical s orbital. As it is in the first shell, this is called the 1s orbital. This can hold up to two electrons. The second shell similarly contains a 2s orbital, but it also contains three dumbbell-shaped p orbitals, and can thus fill up to eight electrons (2×1 + 2×3 = 8). The third shell contains one 3s orbital, three 3p orbitals, and five 3d orbitals, and thus has a capacity of 2×1 + 2×3 + 2×5 = 18. The fourth shell contains one 4s orbital, three 4p orbitals, five 4d orbitals, and seven 4f orbitals, thus leading to a capacity of 2×1 + 2×3 + 2×5 + 2×7 = 32.[16] Higher shells contain more types of orbitals that continue the pattern, but such types of orbitals are not filled in the known elements.[17] The subshell types are characterised by the quantum numbers. Four numbers describe an electron in an atom completely: the principal quantum number n (the shell), the azimuthal quantum number ℓ (the orbital type), the magnetic quantum number mℓ (which of the orbitals of a certain type it is in), and the spin quantum number s.[11]

The sequence in which the orbitals are filled is given by the Aufbau principle, also known as the Madelung or Klechkovsky rule. The shells overlap in energies, creating a sequence as follows:[18]

- 1s ≪ 2s < 2p ≪ 3s < 3p ≪ 4s < 3d < 4p ≪ 5s < 4d < 5p ≪ 6s < 4f < 5d < 6p ≪ 7s < 5f < 6d < 7p ≪ ...

Here the sign ≪ means "much less than" as opposed to < meaning just "less than".[18] Phrased differently, electrons enter orbitals in order of increasing n + ℓ, and if two orbitals are available with the same value of n + ℓ, the one with lower n is occupied first.[17][19]

The overlaps get quite close at the point where the d-orbitals enter the picture,[20] and the order can shift with atomic charge.[21][b]

Starting from the simplest atom, this lets us build up the periodic table one at a time in order of atomic number, by considering the cases of single atoms. In hydrogen, there is only one electron, which must go in the lowest-energy orbital 1s. This configuration is thus written 1s1. Helium adds a second electron, which also goes into 1s and fills the first shell completely.[11]

The third element, lithium, has no more space in the first shell. Its third electron must thus enter the 2s subshell; this its only valence electron, as the 1s orbital is now too close to the nucleus to participate chemically. The 2s subshell is completed by the next element beryllium. The following elements then proceed to fill up the p-orbitals. Boron puts its new electron in a 2p orbital; carbon fills a second 2p orbital; and with nitrogen all three 2p orbitals become singly occupied. This is consistent with Hund's rule, which states that atoms will prefer to singly occupy each orbital of the same type before filling them with the second electron. Oxygen, fluorine, and neon then complete the already singly filled 2p orbitals; the last of these fills the second shell completely.[11]

Starting from element 11, sodium, there is no more space in the second shell, which from here on is a core shell just like the first. Thus the eleventh electron enters the 3s orbital instead. In the table to the right, the configurations have been abbreviated: the 1s2 2s2 2p6 core is abbreviated [Ne], as it is identical to the electron configuration of neon. Magnesium finishes this 3s orbital, and from then on the six elements aluminium, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine, and argon fill the three 3p orbitals. This creates an analogous series in which the outer shell structures of sodium through argon are exactly analogous to those of lithium through neon, and is the basis for chemical periodicity that the periodic table illustrates:[11] at regular but changing intervals of atomic numbers, the properties of the chemical elements approximately repeat.[8]

| Z | Symbol | Element | Electron configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | hydrogen | 1s1 |

| 2 | He | helium | 1s2 |

| 3 | Li | lithium | 1s2 2s1 |

| 4 | Be | beryllium | 1s2 2s2 |

| 5 | B | boron | 1s2 2s2 2p1 |

| 6 | C | carbon | 1s2 2s2 2p2 |

| 7 | N | nitrogen | 1s2 2s2 2p3 |

| 8 | O | oxygen | 1s2 2s2 2p4 |

| 9 | F | fluorine | 1s2 2s2 2p5 |

| 10 | Ne | neon | 1s2 2s2 2p6 |

| 11 | Na | sodium | [Ne] 3s1 |

| 12 | Mg | magnesium | [Ne] 3s2 |

| 13 | Al | aluminium | [Ne] 3s2 3p1 |

| 14 | Si | silicon | [Ne] 3s2 3p2 |

| 15 | P | phosphorus | [Ne] 3s2 3p3 |

| 16 | S | sulfur | [Ne] 3s2 3p4 |

| 17 | Cl | chlorine | [Ne] 3s2 3p5 |

| 18 | Ar | argon | [Ne] 3s2 3p6 |

| 19 | K | potassium | [Ar] 4s1 |

| 20 | Ca | calcium | [Ar] 4s2 |

| 21 | Sc | scandium | [Ar] 3d1 4s2 |

| 22 | Ti | titanium | [Ar] 3d2 4s2 |

| 23 | V | vanadium | [Ar] 3d3 4s2 |

| 24 | Cr | chromium | [Ar] 3d5 4s1 |

| 25 | Mn | manganese | [Ar] 3d5 4s2 |

| 26 | Fe | iron | [Ar] 3d6 4s2 |

| 27 | Co | cobalt | [Ar] 3d7 4s2 |

| 28 | Ni | nickel | [Ar] 3d8 4s2 |

| 29 | Cu | copper | [Ar] 3d10 4s1 |

| 30 | Zn | zinc | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 |

| 31 | Ga | gallium | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p1 |

| 32 | Ge | germanium | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p2 |

| 33 | As | arsenic | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p3 |

| 34 | Se | selenium | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p4 |

| 35 | Br | bromine | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p5 |

| 36 | Kr | krypton | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p6 |

The first eighteen elements can thus be arranged as the start of a periodic table. Elements in the same column have the same number of outer electrons and analogous outer electron configurations: these columns are called groups. The single exception is helium, which has two outer electrons like beryllium and magnesium, but is placed with neon and argon to emphasise that its outer shell is full. There are eight columns in this periodic table fragment, corresponding to at most eight outer electrons.[3] A row begins when a new shell begins filling; these rows are called the periods.[16] Finally, the colouring illustrates the blocks: the elements in the s-block (coloured red) are filling s-orbitals, while those in the p-block (coloured yellow) are filling p-orbitals.[16]

| 1 H |

2 He |

2×1 = 2 elements 1s | ||||||

| 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 2s 2p |

| 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 3s 3p |

Starting the next row, for potassium and calcium the 4s orbital is the lowest in energy, and therefore they fill it. Potassium adds one electron to the 4s shell ([Ar] 4s1), and calcium then completes it ([Ar] 4s2). However, starting from scandium the 3d orbital becomes the next highest in energy. The 4s and 3d orbitals are of approximately the same energy and they compete for filling the electrons, and so the occupation is not quite consistently filling the 3d orbitals one at a time. The precise energy ordering of 3d and 4s changes along the row, and also changes depending on how many electrons are removed from the atom. For example, due to the repulsion between the 3d electrons and the 4s ones, at chromium the 4s energy level becomes slightly higher than 3d, it becomes more profitable to have a [Ar] 3d5 4s1 configuration than an [Ar] 3d4 4s2 one. A similar anomaly occurs at copper.[11] These are violations of the Madelung rule. Such anomalies however do not have any chemical significance,[21] as the various configurations are so close in energy to each other[20] that the presence of a nearby atom can shift the balance.[11] The periodic table therefore ignores these and considers only idealised configurations.[10]

At zinc, the 3d orbitals are completely filled with a total of ten electrons. Next come the 4p orbitals completing the row, which are filled progressively by gallium through krypton, in a manner totally analogous to the previous p-block elements.[11] From gallium onwards, the 3d orbitals form part of the electronic core, and no longer participate in chemistry. The s- and p-block elements, which fill their outer shells, are called main-group elements; the d-block elements (coloured blue below), which fill an inner shell, are called transition elements (or transition metals, since they are all metals).[22]

As 5s fills before 4d, which fills before 5p, the fifth row has exactly the same structure as the fourth.[16]

| 1 H |

2 He |

2×1 = 2 elements 1s | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 2s 2p | ||||||||||

| 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 3s 3p | ||||||||||

| 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

2×(1+3+5) = 18 elements 4s 3d 4p |

| 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

2×(1+3+5) = 18 elements 5s 4d 5p |

The sixth row of the table likewise starts with two s-block elements: caesium and barium. After this, the first f-block elements (coloured green below) begin to appear, starting with lanthanum. These are sometimes termed inner transition elements.[22] As there are now not only 4f but also 5d and 6s subshells at similar energies, competition occurs once again with many irregular configurations;[20] this has resulted in some dispute about where exactly the f-block is supposed to begin, but most who study the matter agree that it starts at lanthanum in accordance with the Aufbau principle.[23] Even though lanthanum does not itself fill the 4f orbital due to repulsion between electrons,[21] its 4f orbitals are low enough in energy to participate in chemistry.[24] At ytterbium, the seven 4f orbitals are completely filled with fourteen electrons; thereafter, a series of ten transition elements (lutetium through mercury) follows,[25][26][27] and finally six main-group elements (thallium through radon) complete the period.[28]

The seventh row is likewise analogous to the sixth row: 7s fills, then 5f, then 6d, and finally 7p.[16] For a very long time, the seventh row was incomplete as most of its elements do not occur in nature. The missing elements beyond uranium started to be synthesised in the laboratory in 1940, when neptunium was made.[29] The row was completed with the discovery of tennessine in 2010[30] (the last element oganesson had already been made in 2002),[31] and the last elements in this seventh row were validated and given names in 2016.[32]

| 1 H |

2 He |

2×1 = 2 elements 1s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 2s 2p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar |

2×(1+3) = 8 elements 3s 3p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

2×(1+3+5) = 18 elements 4s 3d 4p | ||||||||||||||

| 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

2×(1+3+5) = 18 elements 5s 4d 5p | ||||||||||||||

| 55 Cs |

56 Ba |

57 La |

58 Ce |

59 Pr |

60 Nd |

61 Pm |

62 Sm |

63 Eu |

64 Gd |

65 Tb |

66 Dy |

67 Ho |

68 Er |

69 Tm |

70 Yb |

71 Lu |

72 Hf |

73 Ta |

74 W |

75 Re |

76 Os |

77 Ir |

78 Pt |

79 Au |

80 Hg |

81 Tl |

82 Pb |

83 Bi |

84 Po |

85 At |

86 Rn |

2×(1+3+5+7) = 32 elements 6s 4f 5d 6p |

| 87 Fr |

88 Ra |

89 Ac |

90 Th |

91 Pa |

92 U |

93 Np |

94 Pu |

95 Am |

96 Cm |

97 Bk |

98 Cf |

99 Es |

100 Fm |

101 Md |

102 No |

103 Lr |

104 Rf |

105 Db |

106 Sg |

107 Bh |

108 Hs |

109 Mt |

110 Ds |

111 Rg |

112 Cn |

113 Nh |

114 Fl |

115 Mc |

116 Lv |

117 Ts |

118 Og |

2×(1+3+5+7) = 32 elements 7s 5f 6d 7p |

This completes the modern periodic table, with all seven rows completely filled to capacity.[32]

The following table shows the electron configuration of a neutral gas-phase atom of each element. Different configurations can be favoured in different chemical environments.[21] The main-group elements have entirely regular electron configurations; the transition and inner transition elements show a number of irregularities due to the aforementioned competition between subshells close in energy level. For the last ten elements, experimental data is lacking[33] and therefore calculated configurations have been shown instead.[34] Completely filled subshells have been greyed out.

| hide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group: | 1 | 2 | | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||||

| 1s: | 1 H 1 |

2 He 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [He] 2s: 2p: |

3 Li 1 - |

4 Be 2 - |

5 B 2 1 |

6 C 2 2 |

7 N 2 3 |

8 O 2 4 |

9 F 2 5 |

10 Ne 2 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Ne] 3s: 3p: |

11 Na 1 - |

12 Mg 2 - |

13 Al 2 1 |

14 Si 2 2 |

15 P 2 3 |

16 S 2 4 |

17 Cl 2 5 |

18 Ar 2 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Ar] 4s: 3d: 4p: |

19 K 1 - - |

20 Ca 2 - - |

21 Sc 2 1 - |

22 Ti 2 2 - |

23 V 2 3 - |

24 Cr 1 5 - |

25 Mn 2 5 - |

26 Fe 2 6 - |

27 Co 2 7 - |

28 Ni 2 8 - |

29 Cu 1 10 - |

30 Zn 2 10 - |

31 Ga 2 10 1 |

32 Ge 2 10 2 |

33 As 2 10 3 |

34 Se 2 10 4 |

35 Br 2 10 5 |

36 Kr 2 10 6 | ||||||||||||||

| [Kr] 5s: 4d: 5p: |

37 Rb 1 - - |

38 Sr 2 - - |

39 Y 2 1 - |

40 Zr 2 2 - |

41 Nb 1 4 - |

42 Mo 1 5 - |

43 Tc 2 5 - |

44 Ru 1 7 - |

45 Rh 1 8 - |

46 Pd - 10 - |

47 Ag 1 10 - |

48 Cd 2 10 - |

49 In 2 10 1 |

50 Sn 2 10 2 |

51 Sb 2 10 3 |

52 Te 2 10 4 |

53 I 2 10 5 |

54 Xe 2 10 6 | ||||||||||||||

| [Xe] 6s: 4f: 5d: 6p: |

55 Cs 1 - - - |

56 Ba 2 - - - |

57 La 2 - 1 - |

58 Ce 2 1 1 - |

59 Pr 2 3 - - |

60 Nd 2 4 - - |

61 Pm 2 5 - - |

62 Sm 2 6 - - |

63 Eu 2 7 - - |

64 Gd 2 7 1 - |

65 Tb 2 9 - - |

66 Dy 2 10 - - |

67 Ho 2 11 - - |

68 Er 2 12 - - |

69 Tm 2 13 - - |

70 Yb 2 14 - - |

71 Lu 2 14 1 - |

72 Hf 2 14 2 - |

73 Ta 2 14 3 - |

74 W 2 14 4 - |

75 Re 2 14 5 - |

76 Os 2 14 6 - |

77 Ir 2 14 7 - |

78 Pt 1 14 9 - |

79 Au 1 14 10 - |

80 Hg 2 14 10 - |

81 Tl 2 14 10 1 |

82 Pb 2 14 10 2 |

83 Bi 2 14 10 3 |

84 Po 2 14 10 4 |

85 At 2 14 10 5 |

86 Rn 2 14 10 6 |

| [Rn] 7s: 5f: 6d: 7p: |

87 Fr 1 - - - |

88 Ra 2 - - - |

89 Ac 2 - 1 - |

90 Th 2 - 2 - |

91 Pa 2 2 1 - |

92 U 2 3 1 - |

93 Np 2 4 1 - |

94 Pu 2 6 - - |

95 Am 2 7 - - |

96 Cm 2 7 1 - |

97 Bk 2 9 - - |

98 Cf 2 10 - - |

99 Es 2 11 - - |

100 Fm 2 12 - - |

101 Md 2 13 - - |

102 No 2 14 - - |

103 Lr 2 14 - 1 |

104 Rf 2 14 2 - |

105 Db 2 14 3 - |

106 Sg 2 14 4 - |

107 Bh 2 14 5 - |

108 Hs 2 14 6 - |

109 Mt 2 14 7 - |

110 Ds 2 14 8 - |

111 Rg 2 14 9 - |

112 Cn 2 14 10 - |

113 Nh 2 14 10 1 |

114 Fl 2 14 10 2 |

115 Mc 2 14 10 3 |

116 Lv 2 14 10 4 |

117 Ts 2 14 10 5 |

118 Og 2 14 10 6 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

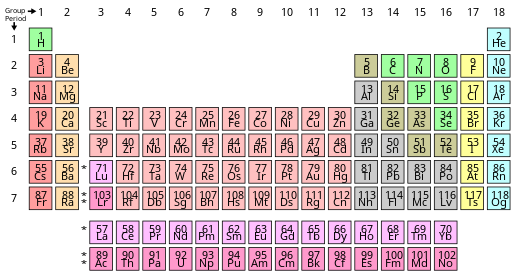

Presentation forms

For reasons of space, the periodic table is commonly presented with the f-block elements cut out and placed as a footnote below the main body of the table, as below.[3][16][35]

| Group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen & alkali metals |

Alkaline earth metals | Pnictogens | Chalcogens | Halogens | Noble gases | ||||||||||||||

| Period 1 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

- Ca: 40.078 — Formal short value, rounded (no uncertainty)[37]

- Po: [209] — mass number of the most stable isotope

Both forms represent the same periodic table.[6] The form with the f-block included in the main body is sometimes called the 32-column[6] or long form;[38] the form with the f-block cut out is sometimes called the 18-column[6] or medium-long form.[38] The 32-column form has the advantage of showing all elements in their correct sequence, but it has the disadvantage of requiring more space.[39]

All periodic tables show the elements' symbols; many also provide supplementary information about the elements, either via colour-coding or as data in the cells. The above table shows the names and atomic numbers of the elements, and also their blocks, natural occurrences and standard atomic weights. For the short-lived elements without standard atomic weights, the mass number of the most stable known isotope is used instead. Other tables may include properties such as state of matter, melting and boiling points, densities, as well as provide different classifications of the elements.[c]

Under an international naming convention, the groups are numbered numerically from 1 to 18 from the leftmost column (the alkali metals) to the rightmost column (the noble gases).[40] Previously, they were known by Roman numerals. In America, the Roman numerals were followed by either an "A" if the group was in the s- or p-block, or a "B" if the group was in the d-block. The Roman numerals used correspond to the last digit of today's naming convention (e.g. the group 4 elements were group IVB, and the group 14 elements were group IVA). In Europe, the lettering was similar, except that "A" was used if the group was before group 10, and "B" was used for groups including and after group 10. In addition, groups 8, 9 and 10 used to be treated as one triple-sized group, known collectively in both notations as group VIII. In 1988, the new IUPAC naming system was put into use, and the old group names were deprecated.[35]

| IUPAC group | 1a | 2 | n/a | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mendeleev (I–VIII) | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | b | |||

| CAS (US, A-B-A) | IA | IIA | IIIB | IVB | VB | VIB | VIIB | VIIIB | IB | IIB | IIIA | IVA | VA | VIA | VIIA | VIIIA | |||

| old IUPAC (Europe, A-B) | IA | IIA | IIIA | IVA | VA | VIA | VIIA | VIII | IB | IIB | IIIB | IVB | VB | VIB | VIIB | 0 | |||

| Trivial name | H and Alkali metalsr | Alkaline earth metalsr | Coinage metals | Triels | Tetrels | Pnictogensr | Chalcogensr | Halogensr | Noble gasesr | ||||||||||

| Name by elementr | Lithium group | Beryllium group | Scandium group | Titanium group | Vanadium group | Chromium group | Manganese group | Iron group | Cobalt group | Nickel group | Copper group | Zinc group | Boron group | Carbon group | Nitrogen group | Oxygen group | Fluorine group | Helium or Neon group | |

| Period 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||

| Period 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||

| Period 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||

| Period 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |

| Period 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | |

| Period 6 | Cs | Ba | La–Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn |

| Period 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac–No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og |

n/a Do not have a group number

b Group 18, the noble gases, were not discovered at the time of Mendeleev's original table. Later (1902), Mendeleev accepted the evidence for their existence, and they could be placed in a new "group 0", consistently and without breaking the periodic table principle.

r Group name as recommended by IUPAC.

Periodic trends

As chemical reactions involve the valence electrons,[3] elements with similar outer electron configurations may be expected to react similarly and form compounds with similar proportions of elements in them.[41] Such elements are placed in the same group, and thus there tend to be clear similarities and trends in chemical behaviour as one proceeds down a group.[42] As analogous configurations return at regular intervals, the properties of the elements thus exhibit periodic recurrences, hence the name of the periodic table and the periodic law. These periodic recurrences were noticed well before the underlying theory that explains them was developed.[43][44]

For example, the valence of an element can be defined either as the number of hydrogen atoms that can combine with it to form a simple binary hydride, or as twice the number of oxygen atoms that can combine with it to form a simple binary oxide (that is, not a peroxide or a superoxide). The valences of the main-group elements are directly related to the group number: the hydrides in the main groups 1–2 and 13–17 follow the formulae MH, MH2, MH3, MH4, MH3, MH2, and finally MH. The highest oxides instead increase in valence, following the formulae M2O, MO, M2O3, MO2, M2O5, MO3, M2O7.[d] The electron configuration suggests a ready explanation from the number of electrons available for bonding,[41] although a full explanation requires considering the energy that would be released in forming compounds with different valences rather than simply considering electron configurations alone.[45] Today the notion of valence has been extended by that of the oxidation state, which is the formal charge left on an element when all other elements in a compound have been removed as their ions.[41]

As elements in the same group share the same valence configurations, they usually exhibit similar chemical behaviour. For example, the alkali metals in the first group all have one valence electron, and form a very homogeneous class of elements: they are all soft and reactive metals. However, there are many factors involved, and groups can often be rather hetereogeneous. For instance, the stable elements of group 14 comprise a nonmetal (carbon), two semiconductors (silicon and germanium), and two metals (tin and lead). They are nonetheless united by having four valence electrons.[46]

Atomic radius

Atomic radii (the size of atoms) generally decrease going left to right along the main-group elements, because the nuclear charge increases but the outer electrons are still in the same shell. However, going down a column, the radii generally increase, because the outermost electrons are in higher shells that are thus further away from the nucleus.[3][47]

In the transition elements, an inner shell is filling, but the size of the atom is still determined by the outer electrons. The increasing nuclear charge across the series and the increased number of inner electrons for shielding somewhat compensate each other, so the decrease in radius is smaller.[47] The 4p and 5d atoms, coming immediately after new types of transition series are first introduced, are smaller than would have been expected.[48]

Ionisation energy

The first ionisation energy of an atom is the energy required to remove an electron from it. This varies with the atomic radius: ionisation energy increases left to right and up to down, because electrons that are closer to the nucleus are held more tightly and are more difficult to remove. Ionisation energy thus is minimised at the first element of each period – hydrogen and the alkali metals – and then generally rises until it reaches the noble gas at the right edge of the period.[3] There are some exceptions to this trend, such as oxygen, where the electron being removed is paired and thus interelectronic repulsion makes it easier to remove than expected.[49]

In the transition series, the outer electrons are preferentially lost even though the inner orbitals are filling. For example, in the 3d series, the 4s electrons are lost first even though the 3d orbitals are being filled. The shielding effect of adding an extra 3d electron approximately compensates the rise in nuclear charge, and therefore the ionisation energies stay mostly constant, though there is a small increase especially at the end of each transition series.[50]

As metal atoms tend to lose electrons in chemical reactions, ionisation energy is generally correlated with chemical reactivity, although there are other factors involved as well.[50]

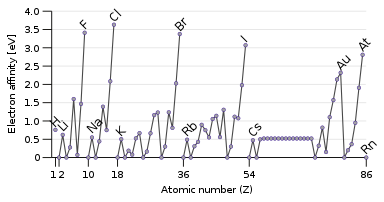

Electron affinity

The opposite property to ionisation energy is the electron affinity, which is the energy released when adding an electron to the atom.[51] A passing electron will be more readily attracted to an atom if it feels the pull of the nucleus more strongly, and especially if there is an available partially filled outer orbital that can accommodate it. Therefore, electron affinity tends to increase down to up and left to right. The exception is the last column, the noble gases, which have a full shell and have no room for another electron. This gives the halogens in the next-to-last column the highest electron affinities.[3]

Some atoms, like the noble gases, have no electron affinity: they cannot form stable gas-phase anions.[52] The noble gases, having high ionisation energies and no electron affinity, have little inclination towards gaining or losing electrons and are generally unreactive.[3]

Some exceptions to the trends occur: oxygen and fluorine have lower electron affinities than their heavier homologues sulfur and chlorine, because they are small atoms and hence the newly added electron would experience significant repulsion from the already present ones. For the nonmetallic elements, electron affinity likewise somewhat correlates with reactivity, but not perfectly since other factors are involved. For example, fluorine has a lower electron affinity than chlorine, but is more reactive.[51]

Electronegativity

Another important property of elements is their electronegativity. Atoms form covalent bonds to each other by sharing electrons in pairs, creating an overlap of valence orbitals. The degree to which each atom attracts the shared electron pair depends on the atom's electronegativity[53] – the tendency of an atom towards gaining or losing electrons.[3] The more electronegative atom will tend to attract the electron pair more, and the less electronegative (or more electropositive) one will attract it less. Electronegativity is likewise dependent on how strongly the nucleus can attract the electron pair, and so it exhibits a similar variation to the other properties already discussed: electronegativity tends to fall going up to down, and rise going left to right. The alkali and alkaline earth metals are among the most electropositive elements, while the chalcogens, halogens, and noble gases are among the most electronegative ones.[53]

Electronegativity is generally measured on the Pauling scale, on which the most electronegative atom (fluorine) is given electronegativity 4.0, and the least electronegative atom (caesium) is given electronegativity 0.79.[3] Electronegativity of an element also somewhat depends on the identity and number of the atoms it is bonded to, as well as how many electrons it has already lost: an atom becomes more electronegative when it has lost more electrons. These effects leave the general trend intact.[53]

Metallicity

A simple substance is a substance formed from atoms of one chemical element. The simple substances of the more electronegative atoms tend to share electrons, forming either discrete covalent molecules (like hydrogen or oxygen) or giant covalent structures (like carbon or silicon). The noble gases simply stay as single atoms. The more electropositive atoms, however, tend to instead lose electrons, creating a "sea" of electrons engulfing cations.[3] The outer orbitals of one atom overlap to share electrons with all its neighbours, creating a giant structure of molecular orbitals extending all over the structure.[54] This negatively charged "sea" pulls on all the ions and keeps them together in a metallic bond. Elements forming such bonds are often called metals.[3] Some elements can form multiple simple substances with different structures: these are called allotropes. For example, diamond and graphite are two allotropes of carbon.[46]

Due to the aforementioned trends, metals are generally found towards the left side of the periodic table, and nonmetals towards the right side. Metallicity tends to be correlated with electropositivity and the willingness to lose electrons, which increases right to left and up to down; therefore, the dividing line between metals and nonmetals is roughly diagonal. Most elements are metals, because the transition series appear to the left of this diagonal. Elements near the borderline tend to have properties that are intermediate between those of metals and nonmetals, and may have some properties characteristic of both. They are often termed semi-metals or metalloids.[3] For example, arsenic has multiple allotropes, but only one conducts electricity like a metal.

The following table considers the most stable allotropes at standard conditions. The elements coloured yellow form simple substances that are well-characterised by metallic bonding. Elements coloured light blue form giant covalent structures, whereas those coloured dark blue form small covalently bonded molecules that are held together by weaker van der Waals forces. The noble gases are coloured in violet: their molecules are single atoms and no covalent bonding occurs. Greyed-out cells are for elements which have not been prepared in sufficient quantities for their most stable allotropes to have been characterised in this way.[e]

| hide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| Group → | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn |

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og |

Metallic Giant covalent Molecular covalent Single atoms Unknown Background color shows bonding of simple substances in the periodic table

Iron, a metal

Sulfur, a nonmetal

Arsenic, an element often called a semi-metal or metalloid

Generally, metals are shiny and dense.[3] They usually have high melting and boiling points due to the strength of the metallic bond, and are malleable and ductile (easily stretched and shaped) because the atoms can move relative to each other without breaking the metallic bond.[56] They conduct electricity because their electrons are free to move in all three dimensions. Similarly, they conduct heat, which is transferred by the electrons as extra kinetic energy: they move faster. These properties persist in the liquid state, as although the crystal structure is destroyed on melting, the atoms still touch and the metallic bond persists, though it is weakened.[56] Metals tend to be reactive towards nonmetals.[3]

Nonmetals exhibit different properties. Those forming giant covalent crystals exhibit high melting and boiling points, as it takes a lot of energy to overcome the strong covalent bonds. Those forming discrete molecules are held together mostly by the intermolecular forces, which are more easily overcame; thus they tend to have lower melting and boiling points,[57] and many are liquids or gases at room temperature.[3] Nonmetals are often dull-looking and reactive with metals (except for the noble gases).[3] They are brittle when solid as their atoms are held tightly in place. They are less dense and conduct electricity poorly,[3] because there are no mobile electrons; the orbitals that overlap to allow delocalisation are too high in energy to reach.[58] However, especially near the borderline, this energy gap is small and electrons can readily cross it when thermally excited. Hence, many elements near the borderline are semiconductors, such as silicon[58] and germanium.[59]

As such, it is common to designate a class of metalloids straddling the boundary between metals and nonmetals, as elements in that region are intermediate in both physical and chemical properties.[3] However, no consensus exists in the literature for precisely which elements should be so designated. When such a category is used, boron, silicon, germanium, arsenic, antimony, and tellurium are usually included; but most sources include other elements as well, without agreement on which extra elements should be added, and some others subtract from this list instead.[f] For example, the periodic table used by the American Chemical Society includes polonium as a metalloid,[60] but that used by the Royal Society of Chemistry does not,[61] and that included in the Encyclopædia Britannica does not refer to metalloids or semi-metals at all.[62]

Further manifestations of periodicity

There are some other relationships throughout the periodic table between elements that are not in the same group, such as the diagonal relationships between elements that are diagonally adjacent (e.g. lithium and magnesium).[63] Some similarities can also be found between the main groups and the transition metal groups, or between the early actinides and early transition metals, when the elements have the same number of valence electrons. Thus uranium somewhat resembles chromium and tungsten in group 6,[63] as all three have six valence electrons.[64]

The first row of every block tends to show rather distinct properties from the other rows, because the first orbital of each type (1s, 2p, 3d, 4f, 5g, etc.) is significantly smaller than would be expected.[65] The degree of the anomaly is highest for the s-block, is moderate for the p-block, and is less pronounced for the d- and f-blocks.[63] There is also an even-odd difference between the periods (except in the s-block) that is sometimes known as secondary periodicity: elements in even periods have smaller atomic radii and prefer to lose fewer electrons, while elements in odd periods (except the first) differ in the opposite direction. Thus, many properties in the p-block show a zigzag rather than a smooth trend along the group. For example, phosphorus and antimony in odd periods of group 15 readily reach the +5 oxidation state, whereas nitrogen, arsenic, and bismuth in even periods prefer to stay at +3.[63][66]

When atomic nuclei become highly charged, special relativity becomes needed to gauge the effect of the nucleus on the electron cloud. These relativistic effects result in heavy elements increasingly having differing properties compared to their lighter homologues in the periodic table. For example, relativistic effects explain why gold is golden and mercury is a liquid.[67][68] These effects are expected to become very strong in the late seventh period, potentially leading to a collapse of periodicity.[69] Electron configurations and chemical properties are only clearly known till element 108 (hassium), so the chemical characterisation of the heaviest elements remains a topic of current research.[70]

Many other physical properties of the elements exhibit periodic variation in accordance with the periodic law, such as melting points, boiling points, heats of fusion, heats of vaporisation, atomisation energy, and so on. Similar periodic variations appear for the compounds of the elements, which can be observed by comparing hydrides, oxides, sulfides, halides, and so on.[53] Chemical properties are more difficult to describe quantitatively, but likewise exhibit their own periodicities. Examples include how oxidation states tend to vary in steps of 2 in the main-group elements, but in steps of 1 for the transition elements; the variation in the acidic and basic properties of the elements and their compounds; the stabilities of compounds; and methods of isolating the elements.[41] Periodicity is and has been used very widely to predict the properties of unknown new elements and new compounds, and is central to modern chemistry.[71]

Classification of elements

| Alkali metals Alkaline earth metals Lanthanides Actinides Transition metals | Other metals Metalloids Other nonmetals Halogens Noble gases |

Many terms have been used in the literature to describe sets of elements that behave similarly. The group names alkali metal, alkaline earth metal, pnictogen, chalcogen, halogen, and noble gas are acknowledged by IUPAC; the other groups can be referred to by their number, or by their first element (e.g., group 6 is the chromium group).[72] Some divide the p-block elements from groups 13 to 16 by metallicity,[62][60] although there is neither a IUPAC definition nor a precise consensus on exactly which elements should be considered metals, nonmetals, or semi-metals (sometimes called metalloids).[62][60][72] Neither is there a consensus on what the metals succeeding the transition metals ought to be called, with post-transition metal and poor metal being among the possibilities having been used.[g] Some advanced monographs exclude the elements of group 12 from the transition metals on the grounds of their sometimes quite different chemical properties, but this is not a universal practice.[73]

The lanthanides are considered to be the elements La–Lu, which are all very similar to each other: historically they included only Ce–Lu, but lanthanum became included by common usage. The rare earth elements (or rare earth metals) add scandium and yttrium to the lanthanides.[72] Analogously, the actinides are considered to be the elements Ac–Lr (historically Th–Lr),[72] although variation of properties in this set is much greater than within the lanthanides.[21] IUPAC recommends the names lanthanoids and actinoids to avoid ambiguity, as the -ide suffix typically denotes a negative ion; however lanthanides and actinides remain common.[72]

Many more categorisations exist and are used according to certain disciplines. In astrophysics, a metal is defined as any element with atomic number greater than 2, i.e. anything except hydrogen and helium.[74] Physics has its own definitions for metals and semi-metals that do not coincide with the chemical idea of metallicity.[75] A few terms are widely used, but without any very formal definition, such as "heavy metal", which has been given such a wide range of definitions that it has been criticised as "effectively meaningless".[76]

The scope of terms varies significantly between authors. For example, according to IUPAC, the noble gases extend to include the whole group, including the very radioactive superheavy element oganesson.[77] However, among those who specialise in the superheavy elements, this is not often done: in this case "noble gas" is typically taken to imply the unreactive behaviour of the lighter elements of the group. Since calculations generally predict that oganesson should not be particularly inert due to relativistic effects, its status as a noble gas is often questioned in this context.[78] Furthermore, national variations are sometimes encountered: in Japan, alkaline earth metals often do not include beryllium and magnesium as their behaviour is different from the heavier group 2 metals.[79]

History

In 1817, German physicist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner began to formulate one of the earliest attempts to classify the elements.[80] In 1829, he found that he could form some of the elements into groups of three, with the members of each group having related properties. He termed these groups triads.[81][82] Chlorine, bromine, and iodine formed a triad; as did calcium, strontium, and barium; lithium, sodium, and potassium; and sulfur, selenium, and tellurium. Today, all these triads form part of modern-day groups.[83] Various chemists continued his work and were able to identify more and more relationships between small groups of elements. However, they could not build one scheme that encompassed them all.[84]

The breakthrough came from the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Although other chemists had found some other versions of the periodic system at about the same time, Mendeleev was the most dedicated to developing and defending his system, and it was his system that most impacted the scientific community.[85] On 17 February 1869, Mendeleev began arranging the elements and comparing them by their atomic weights. He began with a few elements, and over the course of the day his system grew till it encompassed most of the known elements. After finding a consistent arrangement, his printed table appeared the next month in the journal of the Russian Chemical Society.[86] In some cases, there appeared to be an element missing from the system, and he boldly predicted that that meant that the element had yet to be discovered. In 1871, Mendeleev published a long article, including an updated form of his table, that made his predictions for unknown elements explicit. Mendeleev predicted the properties of three of these unknown elements in detail: as they would be missing heavier homologues of boron, aluminium, and silicon, he named them eka-boron, eka-aluminium, and eka-silicon ("eka" being Sanskrit for "one").[86][87]:45

In 1875, the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran, working without knowledge of Mendeleev's prediction, discovered a new element in a sample of the mineral sphalerite, and named it gallium. He isolated the element and began determining its properties. Mendeleev, reading de Boisbaudran's publication, sent a letter claiming that gallium was his predicted eka-aluminium. Although Lecoq de Boisbaudran was initially sceptical, and suspected that Mendeleev was trying to take credit for his discovery, he later admitted that Mendeleev was correct.[88] In 1879, the Swedish chemist Lars Fredrik Nilson discovered a new element, which he named scandium: it turned out to be eka-boron. Eka-silicon was found in 1886 by German chemist Clemens Winkler, who named it germanium. The properties of gallium, scandium, and germanium matched what Mendeleev had predicted.[89] In 1889, Mendeleev noted at the Faraday Lecture to the Royal Institution in London that he had not expected to live long enough "to mention their discovery to the Chemical Society of Great Britain as a confirmation of the exactitude and generality of the periodic law".[90] Even the discovery of the noble gases at the close of the 19th century, which Mendeleev had not predicted, fitted neatly into Mendeleev's scheme as an eighth main group.[91]

After the internal structure of the atom was probed, amateur Dutch physicist Antonius van den Broek proposed in 1913 that the nuclear charge determined the placement of elements in the periodic table.[92] The New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford coined the word "atomic number" for this nuclear charge.[93] The same year, English physicist Henry Moseley using X-ray spectroscopy confirmed van den Broek's proposal experimentally. Moseley determined the value of the nuclear charge of each element from aluminium to gold and showed that Mendeleev's ordering actually places the elements in sequential order by nuclear charge.[94] Nuclear charge is identical to proton count and determines the value of the atomic number (Z) of each element. Using atomic number gives a definitive, integer-based sequence for the elements. Moseley's research immediately resolved discrepancies between atomic weight and chemical properties; these were cases such as tellurium and iodine, where atomic number increases but atomic weight decreases.[92] Although Moseley was soon killed in World War I, the Swedish physicist Manne Siegbahn continued his work up to uranium, and established that it was the element with the highest atomic number then known (92).[95] Based on Moseley and Siegbahn's research, it was also known which atomic numbers corresponded to missing elements yet to be found.[92]

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr applied Max Planck's idea of quantisation to the atom. He concluded that the energy levels of electrons were quantised: only a discrete set of stable energy states were allowed. Bohr then attempted to understand periodicity through electron configurations, surmising that the outer electrons should be responsible for the chemical properties of the elements, and that moving to the next element involved adding one more electron. In 1913, he produced the first electronic periodic table.[96] Wolfgang Pauli later extended the scheme with the four quantum numbers, and formulated his exclusion principle which stated that no two electrons could have the same four quantum numbers. This explained the lengths of the periods in the periodic table (2, 8, 18, and 32), which corresponded to the number of electrons that each shell could occupy.[97] In 1925, Friedrich Hund arrived at configurations close to the modern ones.[98] The Aufbau principle that describes the electron configurations of the elements was first empirically observed by Erwin Madelung in 1926 and published in 1936.[17]

By then, the pool of missing elements from hydrogen to uranium had shrunk to four: elements 43, 61, 85, and 87 remained missing. Element 43 eventually became the first element to be synthesised artificially via nuclear reactions rather than discovered in nature. It was discovered in 1937 by Italian chemists Emilio Segrè and Carlo Perrier, who named their discovery technetium, after the Greek word for "artificial".[99] Elements 61 (promethium) and 85 (astatine) were likewise produced artificially; element 87 (francium) became the last element to be discovered in nature, by French chemist Marguerite Perey.[100] The elements beyond uranium were likewise discovered artificially, starting with Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson's 1940 discovery of neptunium.[29] Glenn T. Seaborg and his team continued discovering transuranium elements, starting with plutonium, and discovered that contrary to previous thinking, the elements from actinium onwards were f-block congeners of the lanthanides rather than d-block transition metals. He thus called them the actinides.[101]

A significant controversy arose with elements 102 through 106 in the 1960s and 1970s, as competition arose between a team of American scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and a team of Soviet scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR). Each team claimed discovery, and in some cases each proposed their own name for the element, creating an element naming controversy that lasted decades.[102] IUPAC at first adopted a hands-off approach, preferring to wait and see if a consensus would be forthcoming. Unfortunately, it was also the height of the Cold War, and it became clear after some time that this would not happen. As such, IUPAC and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) created a (TWG, fermium being element 100) in 1985 to set out criteria for discovery.[103] After some further controversy, these elements received their final names in 1997.[104]

The TWG's criteria were used to arbitrate later element discovery claims from research institutes in Germany, Russia, and Japan.[105] Currently, consideration of discovery claims is performed by a IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party. After priority was assigned, the elements were officially added to the periodic table, and the discoverers were invited to propose their names.[6] By 2016, this had occurred for all elements up to 118, therefore completing the periodic table's first seven rows.[6][106]

In celebration of the periodic table's 150th anniversary, the United Nations declared the year 2019 as the International Year of the Periodic Table, celebrating "one of the most significant achievements in science".[107] Today, the periodic table is among the most recognisable icons of chemistry.[108] IUPAC is involved today with many processes relating to the periodic table: the addition and naming of new elements, recommending group numbers and collective names, determining which elements belong to group 3, and the updating of atomic weights.[6]

Current questions

Although the modern periodic table is standard today, some variation can be found in period 1 and group 3. Discussion is ongoing about the placements of the relevant elements. The controversy has to do with conflicting understandings of whether chemical or electronic properties should primarily decide periodic table placement, and conflicting views of how the evidence should be used.[108] A similar potential problem has been raised by theoretical investigations of the superheavy elements, whose chemistries may not fit their present position on the periodic table.[109]

Period 1

Usually, hydrogen is placed in group 1, and helium in group 18: this is the placement found on the IUPAC periodic table.[6] However, some variation can be found on both these matters.[110]

Like the group 1 metals, hydrogen has one electron in its outermost shell[111] and typically loses its only electron in chemical reactions.[112] It has some metal-like chemical properties, being able to displace some metals from their salts.[112] But hydrogen forms a diatomic nonmetallic gas at standard conditions, unlike the alkali metals which are reactive solid metals. This and hydrogen's formation of hydrides, in which it gains an electron, brings it close to the properties of the halogens which do the same. Moreover, the lightest two halogens (fluorine and chlorine) are gaseous like hydrogen at standard conditions.[112] Hydrogen thus has properties corresponding to both those of the alkali metals and the halogens, but matches neither group perfectly, and is thus difficult to place by its chemistry.[112] Therefore, while the electronic placement of hydrogen in group 1 predominates, some rarer arrangements show either hydrogen in group 17,[113] duplicate hydrogen in both groups 1 and 17,[114][115] or float it separately from all groups.[115][116][110]

Helium is an unreactive noble gas at standard conditions, and has a full outer shell: these properties are like the noble gases in group 18, but not at all like the reactive alkaline earth metals of group 2. Therefore, helium is nearly universally placed in group 18[6] which its properties best match.[110] However, helium only has two outer electrons in its outer shell, whereas the other noble gases have eight; and it is an s-block element, whereas all other noble gases are p-block elements. In these ways helium better matches the alkaline earth metals.[111][110] Therefore, helium outside all groups may rarely be encountered.[116][110] A few chemists have advocated that the electronic placement in group 2 be adopted for helium.[117][118][119][120][121] Such chemical arguments rest on the first-row anomaly trend, as helium as the first s2 element before the alkaline earth metals stands out as anomalous in a way that helium as the first noble gas does not.[117]

Group 3

Published periodic tables show variation regarding the heavier members of group 3, which begins with scandium and yttrium.[117] They are most commonly lanthanum and actinium, but there are many physical and chemical arguments that they should instead be lutetium and lawrencium.[122] A compromise can also sometimes be found, in which the spaces below yttrium are left blank. This leaves it ambiguous if the group only contains scandium and yttrium,[123] or if it also extends to include all thirty lanthanides and actinides.[38]

Based on the electron configurations that were known at the time, lanthanum was initially placed as the first of the 5d elements as it added a d-electron to the preceding element. This made it the third member of group 3, with cerium to lutetium then following as the f-block, which then split the d-block in two.[122] But in 1937, it was found that the 4f subshell completed filling at ytterbium rather than at lutetium as had previously been thought.[117] As such, the Soviet physicists Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz pointed out in 1948 that the new configurations suggested that the first 5d element was lutetium and not lanthanum.[117][124] This avoids the d-block split by letting the f-block precede the d-block in accordance with the Aufbau principle.[38] Several physicists and chemists in the following decades supported this reassignment based on other physical and chemical properties of the elements involved,[63][117] although this evidence has in turn been criticised as having been selectively chosen.[117] Most authors did not make the change.[117]

In 1988, a IUPAC report was published that touched on the matter. While it wrote that electron configurations were in favour of the new assignment of group 3 with lutetium and lawrencium, it instead decided on a compromise where the lower spots in group 3 were instead left blank, because the traditional form with lanthanum and actinium remained popular.[35] This makes the f-block appear with 15 elements despite quantum mechanics dictating that it should have 14, and leaves it unclear if group 3 contains only scandium and yttrium, or if it contains all lanthanides and actinides in addition.[125] This did not stop the debate. Most sources focusing on the question supported the reassignment,[23] but some authors argued instead in favour of the traditional form with lanthanum as the first 5d element,[117][108] sometimes giving rise to furious debate.[126][127] A minority of textbooks accepted the reassignment, but most either showed the older form or the IUPAC compromise.[128]

In 2015 IUPAC began an ongoing project to decide whether lanthanum or lutetium should go in group 3. It considered the question to be "of considerable importance" for chemists, physicists, and students, noting that the variation in published periodic tables on this point typically puzzled students and instructors.[128] A provisional report appeared from it in 2021, which was in favour of lutetium as the first 5d element. The reasons given were to display all elements in order of increasing atomic number, avoid the d-block split, and to have the blocks follow the widths quantum mechanics demands of them (2, 6, 10, and 14).[125] Currently, IUPAC's website on the periodic table still shows the 1988 compromise, but mentions and links to the project in progress.[6]

Superheavy elements

Although all elements up to oganesson have been discovered, of the elements above hassium (element 108), only copernicium (element 112), nihonium (element 113), and flerovium (element 114) have been chemically investigated. These investigations so far have not produced conclusive results.[129] Some of the elements past hassium may behave differently from what would be predicted by extrapolation, due to relativistic effects. For example, extrapolation would suggest that copernicium and flerovium behave as metals, like their respective lighter congeners mercury and lead. However, they have been predicted to possibly exhibit some noble-gas-like properties, even though neither is placed in group 18 with the other noble gases.[129][70] The current experimental evidence still leaves open the question of whether or not this is the case.[129][130] At the same time, oganesson (element 118) is expected to be a solid semiconductor at standard conditions, despite being in group 18.[131]

Some scientists have argued that should these superheavy elements truly have different properties than their position on the periodic table suggests, the periodic table should be altered to place them with more chemically similar elements. On the other hand, others have argued that the periodic table should reflect atomic structure rather than chemical properties, and oppose such a change.[109]

Future extension beyond the seventh period

The most recently named elements completed the seventh row of the periodic table.[6] Future elements would have to begin an eighth row. These elements may be referred to either by their atomic numbers (e.g. "element 119"), or by the IUPAC systematic element names which directly relate to the atomic numbers.[6] All attempts to synthesise such elements have failed so far. Attempts to produce the first two eighth-row elements are either ongoing or planned at laboratories in Russia and Japan.[133][134]

Currently, discussion continues if this future eighth period should follow the pattern set by the earlier periods or not, as calculations predict that by this point relativistic effects should result in significant deviations from the Madelung rule. Various different models have been suggested. All agree that the eighth period should begin like the previous ones with two 8s elements, and that there should then follow a new series of g-block elements filling up the 5g orbitals, but the precise configurations calculated for these 5g elements varies widely between sources. Beyond this 5g series, calculations do not agree on what should follow.[135][136][132][137][138]

It is expected that nuclear stability will prove the decisive factor constraining the number of possible elements, and that it will depend on the balance between the electric repulsion between protons and the strong force binding nucleons together.[139] As nucleons are arranged in shells, just like electrons, a closed shell can significantly increase stability: the known superheavy nuclei exist because of such a shell closure. They are probably close to a predicted island of stability, where superheavy nuclides should have significantly longer half-lives: predictions range from minutes or days, to millions or billions of years.[140][141] However, as the number of protons increases beyond about 126, this stabilising effect should vanish. It is not clear if further-out shell closures would allow heavier elements to exist.[142][143][144][62] At high mass numbers, quark matter may become stable, in which the nucleus is composed of freely flowing up and down quarks instead of binding them into protons and neutrons, creating a continent of stability instead of an island.[145][146]

Even if eighth-row elements can exist, producing them is likely to be difficult, and become increasingly so as atomic number rises.[147] Although the 8s elements are expected to be reachable with present means, the 5g elements are expected to require new technology,[148] if they can be produced at all.[149] Experimentally characterising these elements chemically would also pose a great challenge.[133]

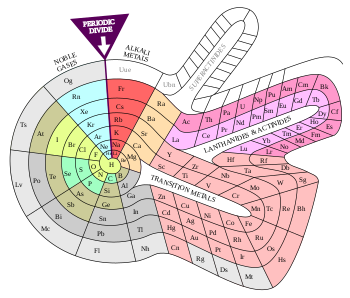

Alternative periodic tables

The periodic law may be represented in multiple ways, of which the standard periodic table is only one.[150] Within 100 years of the appearance of Mendeleev's table in 1869, Edward G. Mazurs had collected an estimated 700 different published versions of the periodic table.[64][151] Many forms retain the rectangular structure, including Charles Janet's left-step periodic table, and the modernised form of Mendeleev's original 8-column layout that is still common in Russia. Other periodic table formats have been shaped much more exotically, such as spirals (Theodor Benfey's pictured to the right), circles, triangles, and even elephants.[152]

Alternative periodic tables are often developed to highlight or emphasize chemical or physical properties of the elements that are not as apparent in traditional periodic tables, with different ones skewed more towards emphasizing chemistry or physics at either end.[153] The standard form, which remains by far the most common, is somewhere in the middle.[153]

The many different forms of periodic table have prompted the questions of whether there is an optimal or definitive form of periodic table, and if so what it might be. There is no current consensus answer, though several forms have been suggested in that capacity.[123][153][154]

| f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | f8 | f9 | f10 | f11 | f12 | f13 | f14 | d1 | d2 | d3 | d4 | d5 | d6 | d7 | d8 | d9 | d10 | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | p5 | p6 | s1 | s2 | |

| 1s | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2s | Li | Be | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2p 3s | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | Na | Mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3p 4s | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | K | Ca | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3d 4p 5s | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | Rb | Sr | ||||||||||||||

| 4d 5p 6s | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | Cs | Ba | ||||||||||||||

| 4f 5d 6p 7s | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | Fr | Ra |

| 5f 6d 7p 8s | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | 119 | 120 |

| f-block | d-block | p-block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ Strictly speaking, one cannot draw an orbital such that the electron is guaranteed to be inside it, but it can be drawn to guarantee a 90% probability of this for example.[13]

- ^ Once two to four electrons are removed, the d and f orbitals usually become lower in energy than the s ones:[21]

- 1s ≪ 2s < 2p ≪ 3s < 3p ≪ 3d < 4s < 4p ≪ 4d < 5s < 5p ≪ 4f < 5d < 6s < 6p ≪ 5f < 6d < 7s < 7p ≪ ...

- ^ See for example the periodic table poster sold by Sigma-Aldrich.

- ^ There are many lower oxides as well: for example, phosphorus in group 15 forms two oxides, P2O3 and P2O5.[41]

- ^ Descriptions of the structures formed by the elements can be found throughout Greenwood and Earnshaw. There are two borderline cases. Arsenic's most stable form conducts electricity like a metal, but the bonding is significantly more localised to the nearest neighbours than it is for the similar structures of antimony and bismuth.[55] Carbon as graphite shows metallic conduction parallel to its planes, but is a semiconductor perpendicular to them.

- ^ See lists of metalloids.

- ^ See post-transition metal.

References

- ^ Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1964). "2. The Relation of Wave and Particle Viewpoints". The Feynman Lectures on Physics. 3. Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02115-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1964). "2. Basic Physics". The Feynman Lectures on Physics. 1. Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02115-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Gonick, First; Criddle, Craig (2005). The Cartoon Guide to Chemistry. Collins. pp. 17–65. ISBN 0-06-093677-0.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Atomic number". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00499

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Chemical element". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01022

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Periodic Table of Elements". iupac.org. IUPAC. 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights (2019). "Standard Atomic Weights". www.ciaaw.org. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scerri, p. 17

- ^ "periodic law". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jensen, William B. (2009). "Misapplying the Periodic Law" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 86 (10): 1186. Bibcode:2009JChEd..86.1186J. doi:10.1021/ed086p1186. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1964). "19. The Hydrogen Atom and The Periodic Table". The Feynman Lectures on Physics. 3. Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02115-3.

- ^ Petrucci et al., p. 323

- ^ Petrucci et al., p. 306

- ^ Petrucci et al., p. 322

- ^ Ball, David W.; Key, Jessie A. (2011). Introductory Chemistry – 1st Canadian Edition. BCcampus. ISBN 978-1-77420-003-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Petrucci et al., p. 331

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Goudsmit, S. A.; Richards, Paul I. (1964). "The Order of Electron Shells in Ionized Atoms" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 51 (4): 664–671 (with correction on p 906). Bibcode:1964PNAS...51..664G. doi:10.1073/pnas.51.4.664. PMC 300183. PMID 16591167.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ostrovsky, V. N. (May 2001). "What and How Physics Contributes to Understanding the Periodic Law". Foundations of Chemistry. 3: 145–181. doi:10.1023/A:1011476405933.

- ^ Wong, D. Pan (1979). "Theoretical justification of Madelung's rule". J. Chem. Educ. 56 (11): 714–718. Bibcode:1979JChEd..56..714W. doi:10.1021/ed056p714.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Petrucci et al., p. 328

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jørgensen, Christian (1973). "The Loose Connection between Electron Configuration and the Chemical Behavior of the Heavy Elements (Transuranics)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 12 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1002/anie.197300121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petrucci et al., pp. 326–7

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jensen, William B. (2015). "The positions of lanthanum (actinium) and lutetium (lawrencium) in the periodic table: an update". Foundations of Chemistry. 17: 23–31. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9216-1. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Hamilton, David C. (1965). "Position of Lanthanum in the Periodic Table". American Journal of Physics. 33 (8): 637–640. doi:10.1119/1.1972042.

- ^ Jensen, W. B. (2015). "Some Comments on the Position of Lawrencium in the Periodic Table" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Wang, Fan; Le-Min, Li (2002). "镧系元素 4f 轨道在成键中的作用的理论研究" [Theoretical Study on the Role of Lanthanide 4f Orbitals in Bonding]. Acta Chimica Sinica (in Chinese). 62 (8): 1379–84.

- ^ Xu, Wei; Ji, Wen-Xin; Qiu, Yi-Xiang; Schwarz, W. H. Eugen; Wang, Shu-Guang (2013). "On structure and bonding of lanthanoid trifluorides LnF3 (Ln = La to Lu)". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2013 (15): 7839–47. Bibcode:2013PCCP...15.7839X. doi:10.1039/C3CP50717C. PMID 23598823.

- ^ Chi, Chaoxian; Pan, Sudip; Jin, Jiaye; Meng, Luyan; Luo, Mingbiao; Zhao, Lili; Zhou, Mingfei; Frenking, Gernot (2019). "Octacarbonyl Ion Complexes of Actinides [An(CO)8]+/− (An=Th, U) and the Role of f Orbitals in Metal–Ligand Bonding". Chem. Eur. J. 25 (50): 11772–11784. doi:10.1002/chem.201902625.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scerri, p. 354–5

- ^ Oganessian, Yu.Ts.; Abdullin, F.Sh.; Bailey, P.D.; Benker, D.E.; Bennett, M.E.; Dmitriev, S.N.; et al. (2010). "Synthesis of a new element with atomic number Z = 117". Physical Review Letters. 104 (14): 142502. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104n2502O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.142502. PMID 20481935. S2CID 3263480.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. T.; et al. (2002). "Results from the first 249

Cf+48

Ca experiment" (PDF). JINR Communication. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2009. - ^ Jump up to: a b Staff (30 November 2016). "IUPAC Announces the Names of the Elements 113, 115, 117, and 118". IUPAC. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (August 2019). "Periodic Table of the Elements". www.nist.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Fricke, B. (1975). Dunitz, J. D. (ed.). "Superheavy elements a prediction of their chemical and physical properties". Structure and Bonding. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 21: 89–144. doi:10.1007/BFb0116496.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fluck, E. (1988). "New Notations in the Periodic Table" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 60 (3): 431–436. doi:10.1351/pac198860030431. S2CID 96704008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Meija, Juris; et al. (2016). "Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 88 (3): 265–91. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

- ^ Meija, Juris; et al. (2016). "Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 88 (3). Table 2, 3 combined; uncertainty removed. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Thyssen, P.; Binnemans, K. (2011). Gschneidner Jr., K. A.; Bünzli, J-C.G; Vecharsky, Bünzli (eds.). Accommodation of the Rare Earths in the Periodic Table: A Historical Analysis. Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. 41. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 1–94. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53590-0.00001-7. ISBN 978-0-444-53590-0.

- ^ Scerri, p. 375

- ^ Connelly, N. G.; Damhus, T.; Hartshorn, R. M.; Hutton, A. T. (2005). Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations 2005 (PDF). RSC Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-85404-438-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 27–9

- ^ Messler, R. W. (2010). The essence of materials for engineers. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7637-7833-0.

- ^ Myers, R. (2003). The basics of chemistry. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 61–67. ISBN 978-0-313-31664-7.

- ^ Chang, R. (2002). Chemistry (7 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 289–310, 340–42. ISBN 978-0-07-112072-2.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 113

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scerri, pp. 14–15

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Jim (2012). "Atomic and Ionic Radius". Chemguide. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 29

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 24–5