Pyongyang Metro

This article needs to be updated. (January 2021) |

| |||

Type D (Puhung Station) | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Native name | 평양 지하철도 P'yŏngyang Chihach'ŏlto | ||

| Locale | |||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 2[1] | ||

| Line number | Chollima Line Hyoksin Line | ||

| Number of stations | 16 (Chollima Line : 8, Hyoksin Line : 8)[1] | ||

| Daily ridership | 400,000 (Weekdays) 700,000 (Holidays) (July 2019)[1] | ||

| Headquarters | Pyongyang Metro, City Metro Unit, Railway Section, Transport and Communication Commission, Pyongyang, Democratic People's Republic of Korea | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | September 1973[2] | ||

| Operator(s) | Pyongyang Metro Administration Bureau[1][2] | ||

| Character | Underground railway | ||

| Number of vehicles | 220 (Type D : 216,[3] Type 1 : 4[4]) | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 22.5 km (14.0 mi)[1][2] | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| Top speed | 70 km/h (43 mph) (Type D) | ||

| |||

| Pyongyang Metro | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

|---|---|

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Pyeongyang Jihacheoldo |

| McCune–Reischauer | P'yŏngyang Chihach'ŏldo |

The Pyongyang Metro (Korean: 평양 지하철도; MR: P'yŏngyang Chihach'ŏlto) is the rapid transit system in the North Korean capital Pyongyang. It consists of two lines: the Chollima Line, which runs north from Puhŭng Station on the banks of the Taedong River to Pulgŭnbyŏl Station, and the Hyŏksin Line, which runs from Kwangbok Station in the southwest to Ragwŏn Station in the northeast. The two lines intersect at Chŏnu Station.

Daily ridership is estimated to be between 300,000 and 700,000.[5][6] Structural engineering of the Metro was completed by North Korea, with rolling stock and related electronic equipment imported from China.[7][8][9] This was later replaced with rolling stock acquired from Germany.[10]

The Pyongyang Metro has a museum devoted to its construction and history.

Construction[]

Construction of the metro network started in 1965, and stations were opened between 1969 and 1972 by president Kim Il-sung.[11] Most of the 16 public stations were built in the 1970s, except for the two most grandiose stations—Puhŭng and Yŏnggwang, which were constructed in 1987. According to NK News sources, construction accidents in the 1970s may have killed dozens of workers.[12]

China had provided technical aid for the metro's construction, sending experts to install equipment made in China, including electrical equipment made in Xiangtan, Hunan[13] and the escalator with vertical height of 64 m made in Shanghai.[14][15]

Pyongyang Metro is among the deepest metros in the world, with the track at over 110 metres (360 ft) deep underground; the metro does not have any above-ground track segments or stations. Due to the depth of the metro and the lack of outside segments, its stations can double as bomb shelters, with blast doors in place at hallways.[16][17] It takes three and a half minutes from the ground to the platform by escalator. The metro is so deep that the temperature of the platform maintains a constant 18 °C (64 °F) all year.[18] The Saint Petersburg Metro also claims to be the deepest, based on the average depth of all its stations. The Arsenalna station on Kyiv Metro's Sviatoshynsko-Brovarska Line is currently the deepest station in the world at 105.5 metres (346 ft).[19] The Porta Alpina railway station, located above the Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland, was supposed to be 800 m (2,600 ft) underground, but the project was indefinitely shelved in 2012.[20]

The system was initially electrified at 825 Volts, but lowered down to 750 Volts to support operation of the Class GI sets.[21]

In 2012, Korean Central Television released renders of a new station bearing the name Mangyongdae displayed at the Pyongyang Architectural Festival.[22]

In 2018, commercial satellite imagery revealed possible extensions to the metro system, with activity showing three possible new underground facilities being constructed to the west of Kwangbok Station. NK News sources speculated an absence of announcements from state media was due to funding issues, as well as due to the 1970s tunneling accidents.[12]

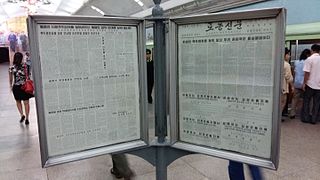

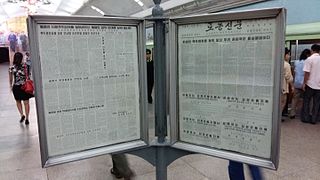

In 2019, Kaeson station and Tongil Station were modernised,[23] adding TVs that show the next service and brighter lighting. This was followed by Jonu station and Chonsung station in 2020.[24] The TVs can also display a digital version of the Rodong Sinmun.

At the 8th Congress of the Workers' Party of Korea, it was announced to push forward on the updating and renovation of the Pyongyang Metro, along with the production of new-type subway trains.[25]

Operation[]

The Pyongyang Metro was designed to operate every few minutes. During rush hour, the trains can operate at a minimum interval of two minutes. The trains have the ability to play music and other recordings.[26] In actual service, they run at every 3 minutes in rush hour and every 5 minutes throughout the day.[27]

The Pyongyang Metro is the cheapest in the world to ride, at only five North Korean won (worth half of a US cent) per ticket.[28] Instead of paper tickets, the Metro previously used an aluminium token, with the emblem of the Metro minted on it and the Korean "지". It has used a paper ticket system, with "지" printed with blue ink on it.[27] Tickets are bought at station booths. Nowadays, the network uses contactless cards that feature the logo of the network and a train set on the front, with the terms and conditions on the other side. Gates display the number of trips remaining on the card, with a trip being a tap on entry and exit.[27] Smoking and eating inside the Metro system is prohibited and is punishable by a large fine.

Network[]

The Pyongyang Metro network consists of two lines:

- Chollima Line, named after a winged horse from ancient Korean mythology. It spans about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi). Construction started in 1968, and the line opened on September 6, 1973. The Mangyongdae Line forms part of the Chollima Line. The total route contains the Puhung, Yonggwang, Ponghwa, Sŭngni, Tongil, Kaeson, Jonu, and Pulgunbyol stations.

- Hyŏksin Line, which literally means renewal, spans about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi). Regular service started on October 9, 1975. The route contains the Kwangbok, Konguk, Hwanggumbol, Konsol, Hyoksin, Jonsung, Samhung, and Rakwon stations. The closed Kwangmyong station is located between the Samhung and Rakwon stations.

The two lines have a linking track, located somewhere near Jonsung station.[29]

Unlike most railway systems, the majority of the stations' names do not refer to their respective locations; instead, stations take their names from themes and characteristics reflecting . A notable exception, Kaesŏn Station ("Triumph station"), is located at the Arch of Triumph.

The network runs entirely underground. The design of the network was based on metro networks in other communist countries, in particular the Moscow Metro.[30] Both networks share many characteristics, such as the great depth of the lines (over 100 metres (330 ft)) and the large distances between stations. Another common feature is the Socialist realist art on display in the stations - such as murals and statues.[31] Staff of the Metro have a military-style uniform that is specific to these workers. Each Metro station has a free toilet for use by patrons. Stations also play state radio-broadcasts and have a display of the Rodong Sinmun newspaper.

In times of war, the metro stations can serve as bomb shelters.[32] For this purpose the stations are fitted with large steel doors.[33] Some sources claim that large military installations are connected to the stations,[34] and also that there exist secret lines solely for government use.[5][35]

One station, Kwangmyŏng, has been closed since 1995 due to the mausoleum of Kim Il-sung being located at that station. Trains do not stop at that station.

The map of the Hyŏksin line shows two additional stations after Kwangbok: (영웅) and (칠골), both of them reportedly under development. The map of the Chollima Line, on the other hand, shows four additional stations, two at each end of the line— (련못), (서포), (청춘) and (만경대)—also planned or under development. However, the most recent maps omit these stations.[27]

In addition to the main system for passenger use, there is reportedly an extra system for government use, similar to Moscow's Metro-2. The secret Pyongyang system supposedly connects important government locations.[36] There is also reportedly a massive underground plaza for mobilization, as well as an underground road connecting two metro stations.[37]

Rolling stock[]

When operations on the Metro started in the 1970s, newly built DK4 passenger cars were used, made for North Korea by the Chinese firm Changchun Railway Vehicles. A prototype train of DK4 cars was constructed in 1971 and the first 15 cars were sent to Pyongyang on July 30, 1973. 112 cars had been provided to North Korea by September 1978,[15] but eventually 345 cars were acquired.[38]

In 1974, Kim Jong-il rode a Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works built metro set named 'Autonomy', but is no longer in service and said to be stored in the Pyongyang Metro museum.[39]

Some of the Chinese-made rolling stock was later sold back to China for use on the Beijing Subway, where it was used in three-car sets on line 13. It has since been replaced by newer DKZ5 and DKZ6 trainsets, and it is not known if the DK4 units were returned to Pyongyang. Other sets have been observed operating near the Sinuiju area.[21]

Since 1997, the Pyongyang Metro has used former German rolling stock from the Berlin U-Bahn.[40] The North Korean government supposedly bought more than twice the number of trainsets required for daily use, prompting speculation that the Metro might contain hidden lines and/or stations that are not open to the public.[36] There are likely three different types of rolling stock in operation:

- Underground Electric Vehicle Type 1, 4 cars built 2015.[41]

- D ("Dora"), former West Berlin stock, 126 cars built between 1957 and 1965.[42]

- DK4, built by CNR Changchun Railway Vehicles. Although only photographed in service up to 2007, one four-car train unit remained in the metro's fleet as a vintage train for special occasions.

The trainsets were given a new red and cream livery in Pyongyang.[40] All advertising was removed and replaced by portraits of leaders, Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. In 2000, a BBC reporter saw "old East German trains complete with their original German graffiti".[10] According to Koryo Tours, they are actually from West Germany.[40] After about 2006, Type D cars were mainly used. The Class GI rolling stock was withdrawn from Metro service in 2001, and those cars are now operating on the railway network around Pyongyang and northern regions as commuter trains.[43][44] One Type D metro car appears to have been converted into a departmental vehicle, with a subsequently installed second driver's cab at the car's back next to the inter carriage door. The metro car is painted in yellow with red warning trims.[45]

In 2015, Kim Jong-un rode a newly manufactured four car train set which was reported to have been developed and built at Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works in North Korea,[46] although the cars appeared to be significantly renovated D-class cars. This set is named 'Underground Electric Vehicle No. 1'. It features a VVVF control and initially fitted with an asynchronous motor but later replaced with a permanent magnet synchronous motor developed by the Kim Chaek University of Technology. It usually runs on the Chollima Line but has also ran on the Hyoksin Line.[41]

Some class D sets have a next stop indicator installed, replacing the portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il.[45]

The shunting locomotives used on the Pyongyang Metro are the GKD5B diesel electric model manufactured by China's CNR Dalian, imported in early 1996.[47]

As a gift to the 8th Congress of the Workers' Party of Korea, it is reported that the Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works are working to complete new metro cars, promoted by the 80 day campaign.[48] However, in the Korean Central News Agency article summarising the eighty day campaign, there was no mention of any new vehicles being produced.[49] Previously, it was reported that a 4 door set was to be manufactured to mainly run on the Hyoksin line, to be named Underground Electric Vehicle No. 2.[41]

| Image | Type | Maximium Speed | Traction | Built | Manufacturer | Country of Origin | No. of Cars | Number Range | Disposition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DK4 | 90 Km/h | Resistor Control | 1971-1978 | CNR Changchun Railway Vehicles | China | Unknown

(112 or 345) |

001 to 1xx | Set beginning with 001is likely retained as a special vehicle[50] | Derivative of the Beijing Subway's DK3 Series.

|

| 4-axle trailer car | Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works | North Korea | 2xx | 4 axle trailer cars built to lengthen DK4 sets to 3 or 4 cars.[51] | ||||||

| [1] | G "Gisela" | 70 km/h | Resistor Control | 1978-1983 | LEW Hennigsdorf | GDR | 120 | 5xx | Retired in 2001 | Ex-BVG trains from the Berlin U-Bahn bought second-hand in 1996-1997

|

|

D "Dora" | 70 km/h | Resistor Control | 1957 to 1965

Bought in 1999 |

O&K, DWM, AEG, Siemens | FRG | 108

(27 4-car sets) |

7xx, 8xx and 9xx | In service | Ex-BVG trains from the Berlin U-Bahn bought second-hand in 1999 |

|

Underground Electric Vehicle No. 1 | Unknown | IGBT-VVVF Inverter and PMSM motors | 2015 | Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works (with Chinese-built components) | DPRK | 4

(1 Set) |

1xx (101 to 104) | In service | |

| [2] | Jaju-ho | Unknown | Unknown

(possibly Resistor Control) |

Unknown (before 1974) | Kim Chong-t'ae Electric Locomotive Works | DPRK | Unknown

(at least 2 cars) |

N/A | Unknown | Prototype train. Supposedly stored in the Pyongyang Metro Museum.

Name means self reliance. |

| [3] | GKD5B | 45 km/h[52] | 12V135Z Diesel engine | 1996-1997 | CNR Dalian | China | 2 | In service | Diesel-electric shunting locomotives

Used to haul metro trains under overhead section from tunnel portal to depot. |

Tourism[]

In general, tourism in North Korea is allowed only in guided groups with no diversion allowed from pre-planned itineraries. Foreign tourists used to be allowed to travel only between Puhŭng Station and Yŏnggwang Station.[53] However, foreign students were allowed to freely use the entire metro system.[54] Since 2010, tourists have been allowed to ride the metro at six stations,[55] and in 2014, all of the metro stations were opened to foreigners. University students traveling with the have also reported visiting every station.[56]

As of 2014, it is possible for tourists on special Public Transport Tours to take metro rides through both lines, including visits to all stations.[57] In April 2014, the first tourist group visited stations on both metro lines, and it is expected that such extended visits to both metro lines will remain possible for future tourist groups.[58]

The previously limited tourist access gave rise to a conspiracy theory that the metro was purely for show. It was claimed that it only consisted of two stops and that the passengers were actors.[59][60][61]

Museum[]

Pyongyang Metro has its own museum. A large portion of the collection is related to President Kim Il-sung providing "on-the-spot guidance" to the workers constructing the system. Among the exhibits are a special funicular-like vehicle which the president used to descend to a station under construction (it rode down the inclined tunnels that would eventually be used by the escalators), and a railbus in which he rode around the system.[62][63] The museum also has a map of the planned lines; it shows the Chollima and Hyoksin line terminating at a common station near Chilgol, the third line that would cross the Taedong River, eventually terminating near Rakrang and the locations of the depots, one far past the western terminus of the Hyoksin line and the depot in Sopo for the Chollima line.[64]

Gallery[]

Mural at Puhŭng Station entrance

Staff in a military-style uniform

A public newspaper display on a platform

A statue of Kim Il-sung at Kaesŏn Station

Socialist realist mural at Ponghwa Station

9 September 2015 newspaper at Puhŭng Station

Escalators at Puhŭng Station

Chandelier at Yŏnggwang Station

Mural at Puhŭng Station

Pyongyang Metro map at Kaesŏn Station

Pyongyang Metro ticket

New train was introduced in 2016

Network Map[]

See also[]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e 平壌地下鉄 - 西船junctionどっと混む (in Japanese)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c 평양 지하철도 - 나무위키 (in Korean)

- ^ 平壌地下鉄 D型 - 西船junctionどっと混む (in Japanese)

- ^ 平壌地下鉄 1型 - 西船junctionどっと混む (in Japanese)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harris, Mark Edward; Cumings, Bruce (2007). Inside North Korea. Chronicle Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8118-5751-2.

- ^ "CNN Special Investigations Unit: Notes from North Korea". CNN. 11 May 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ 关于朝鲜地铁最早是中国修建的说法是真的吗? (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "China Releases Details on Aid to N.Korea". Choson Ilbo. 28 April 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ 中国第一笔援助是对朝鲜提供 平壤地铁系我援建 (in Chinese). 中国网. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lister, Richard (8 October 2000). "Life in Pyongyang". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- ^ 철도동호회 - 조선국 평양지하철도. Daum 카페 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Carroll, Chad (25 April 2018). "North Korea extending Pyongyang metro system, sources say". NK News. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019.

- ^ 湘潭电机股份有限公司地铁产品. Xiangtan Electric Manufacturing Company Limited (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ 罗菁 (31 October 2014). 申城38年援建国外198个成套项目 平壤地铁电梯为沪产 (in Chinese). 东方网. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 李永林主编. 《吉林省志·卷三十三·对外经贸志》 (in Chinese). pp. 444–445. ISBN 7206022952.

- ^ Davies, Elliott (16 April 2016). "I was part of the first group of outsiders allowed to ride the entire North Korean subway system — here's what I saw". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ 平壤的表情:你不知道的朝鲜 (in Chinese). Netease. 31 July 2007. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ 任力波 (17 February 2005). 平壤地铁 站台内常年保持18摄氏度恒温 (in Chinese). Xinhua. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Официальный сайт киевского метрополитена. Kyiv Metro.

- ^ "World's Longest Tunnel Drilled Under Swiss Alps". DNews. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 平壌地下鉄-車両紹介. 2427junction.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Pyongyang — Underground — New stations". transphoto.org. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Video ‘’Revolutionary History in the Pyongyang Subway [CC‘’ showing modernised stations]

- ^ "Underground Pyongyang Is Getting Young". KCNA Watch. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Great programme for struggle leading Korean-style socialist construction to fresh victory: On report made by Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un at Eighth Congress of WPK". The Pyongyang Times. KCNA. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ One minute riding the Pyongyang metro to the tune of Rossini's "il barbiere di siviglia". YouTube. 25 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d 平壌地下鉄. 2427junction.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Hooi, Ng Si (6 September 2008). "A world of its own". The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "平壌地下鉄 革新線". 2427junction.com. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Korea: North-South nuclear issues : hearing before the Subcommittee on Asian and Pacific Affairs of the Committee on Foreign Relations, House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, second session, July 25, 1990. U.S. G.P.O. 1991. p. 85.

- ^ Ishikawa, Shō (1988). The country aglow with Juche: North Korea as seen by a journalist. Foreign languages Pub. House. p. 65.

- ^ Robinson, Martin; Bartlett, Ray; Whyte Rob (2007). Korea. Lonely Planet. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-74104-558-1.

- ^ Springer, Chris (2003). Pyongyang: the hidden history of the North Korean capital. Entente Bt. p. 125. ISBN 978-963-00-8104-7.

- ^ Min, Park Hyun (20 August 2007). "Pyongyang Subway Submerged in Water". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- ^ "Kim Jong-il 'Has Secret Underground Escape Route'". The Chosun Ilbo. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Pyongyang Metro: Statistics". pyongyang-metro.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Mammoth Underground Square and Road in Pyongyang". Digital Chosunilbo (English Edition) : Daily News in English About Korea. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "The Pyongyang Metro: Trains". pyongyang-metro.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ 鉄道省革命事績館 [Korean State Railway Museum]. 2427junction.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Pyongyang Metro | North Korea Travel Guide". Koryo Tours. 29 January 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c 平壌地下鉄-地下電動車1号(100形). 2427junction.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "North Korea, Metro — Vehicle Statistics". transphoto.org. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Metro News". pyongyangmetro.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Photo: Anju — S-bahn; Pyongyang — Underground — Cars". transphoto.org. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 平壌地下鉄-D型. 2427junction.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ North Korea Leadership Watch (19 November 2015). "Kim Jong Un Rides the PY Subway". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ 李炳华. 大连机车车辆厂为朝鲜地铁工程提供GKD5型调车内燃机车. 内燃机车 (in Chinese) (1997年第01期). Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ 지하전동차생산이 마감단계에서 추진되고있다 [Underground electric vehicle production is being promoted at the closing stage.]. dprktoday.com (in Korean). 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "KCNA reports on successful conclusion of 80-day campaign". The Pyongyang Times. KCNA. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Pyongyang's Transport of Delight". Archived from the original on 20 March 2003.

- ^ "ピョンヤン市内をゆく(3)~地下鉄に乗るっ!~ | 長いブログ (旧:ぶらり北朝鮮)". gamp.ameblo.jp. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "GKD5B Diesel-electric Locomotive (Exported to North Korea)".

- ^ Burdick, Eddie (2010). Three Days in the Hermit Kingdom: An American Visits North Korea. McFarland. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7864-4898-2.

- ^ Abt, Felix (2014). A Capitalist in North Korea: My Seven Years in the Hermit Kingdom. Tuttle Publishing. p. 226. ISBN 9780804844390.

- ^ "North Korea". testroete.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Pyongyang metro - 6 stops visited in April 2014. YouTube. 25 April 2014.

- ^ Pyongyang Travel. "Public Transport Tours - Information Page". pyongyang-travel.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ "Tourists granted rare access to nearly all stations on Pyongyang metro network". nknews.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Kate Whitehead (13 September 2013). "Touring North Korea: What's real, what's fake?". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ Hamish Macdonald (2 May 2014). "Tourists granted rare access to nearly all stations on Pyongyang metro network". NK News. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Maeve Shearlaw (13 May 2014). "Mythbusters: uncovering the truth about North Korea". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ The forbidden railway: Vienna - Pyongyang 윈 - 모스크바 - 두만강 - 평양. vienna-pyongyang.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxjNF8ebN1g Archived 31 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Pyongyang Metro Museum photo collection showing the exhibits

- ^ "Pyongyang — Metro museum". transphoto.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Pyongyang Metro, Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1980

- Пхеньянский метрополитен. Путеводитель. — КНДР: Издательство «Корея», 1988.

Further reading[]

- "Kim Jong-il 'Has Secret Underground Escape Route'". The Chosun Ilbo. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Gu Gwang-ho (June 2011). "Inspection At The Metro Station Entrance - "No Shabby Cloths, No Large Luggage!"". Rimjingang. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Pyongyang Metro (category) |

- TOURS BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATIONS - DPR Korea Tour (in English)

- TRAFFIC FANS TOUR - DPR Korea Tour (in English)

- 평양지하철 비공식 홈페이지 (in Korean)

- 평양 지하철도 - 나무위키 (in Korean)

- 平壌地下鉄 - 西船junctionどっと混む (in Japanese)

- Pyongyang Metro - UrbanRail.Net (Wayback Machine) (in English)

- Pyongyang Metro - Steve Gong • Photo | Video (in English)

- Pyongyang Real Distance Metro Map (in English)

- Photos of all Metro stations (in English)

- Video of all Metro stations (in English)

- Pyongyang Metro

- Transport in Pyongyang

- Rapid transit in North Korea

- Underground rapid transit in North Korea

- Standard gauge railways in North Korea

- 1973 establishments in North Korea

- Railway lines opened in 1973