Qila Rai Pithora

| Lal Kot | |

|---|---|

Lal Kot - The fort built by Anangpal Tomar | |

| Location | Mehrauli, Delhi, India |

| Coordinates | 28°31′N 77°11′E / 28.52°N 77.18°E |

| Built | c. 1052 – c.1060 CE |

| Original use | Fortress of Tomara dynasty |

| Architect | Anangpal Tomar |

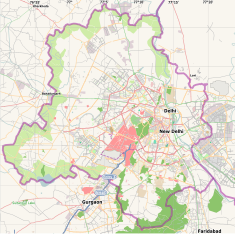

Location in Delhi, India, Asia | |

Lal Kot (lit. "Red Fort") or Qila Rai Pithora (lit. "Rai Pithora's Fort") is a fortified complex in present-day Delhi, which includes the Qutb Minar complex. It was constructed in the reign of Tomar king Anangpal Tomar between c. 1052 - c.1060 CE. It is termed as the "First city of Delhi". Remains of the fort walls are scattered across South Delhi, visible in present Saket, Mehrauli around Qutb complex, Sanjay Van, Kishangarh and Vasant Kunj areas.[1]

Association with Anangpal Tomar II - Lal Kot[]

The Lal Kot (as the Qila Rai Pithora was originally called) is believed to be constructed in the reign of Tomar king Anangpal II. He brought the iron pillar from Saunkh location (Mathura) and got it fixed in Delhi in the year 1052 as evident from the inscriptions on it. By assuming the iron pillar as center, numerous palaces and temples were built and finally the fort Lal Kot was built around them. The construction of the Lal Kot finished in the year 1060. The circumference of the fort was more than 2 miles and the walls of the fort were 60 feet long and 30 feet thick.[2]

“Anangpal II was instrumental in populating Indraprastha and giving it its present name, Delhi. The region was in ruins when he ascended the throne in the 11th century, it was he who built Lal Kot fort (Qila Rai Pithora) and Anangtal Baoli. The Tomar rule over the region is attested by multiple inscriptions and coins, and their ancestry can be traced to the Pandavas (of the Mahabharata)" said BR Mani, former joint director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).[3]

Lal Kot was Delhi’s original ‘red fort’. What we call Red Fort or Lal Qila today was originally called Qila-e-Mubarak built by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan.[4]

A short inscription on the Qutb Minar reads "Pirathi Nirapa", which some writers read as vernacular for "King Prithvi". Some coins, called "Dehliwalas" in the early sources of the Delhi Sultanate, were issued by a series of kings which include the Tomara rulers and a king called "Prithipala".[5] This King Prithvi or Prithipala is believed to be the 3rd last Tomar king of Delhi - Prithvipal Tomar. Due to his name being similar to the famous King Prithviraj Chauhan of that time, he has been completely overlapped in the history.[6]

Hasan Nizami, a Persian author who wrote Tajul-Ma'asir, the first official history of the Delhi Sultanate praised the Lal Kot as follows - "After settling the case of Ajmer, the conqueror (Shahabuddin Ghori) came to Delhi, which was among the major cities of Hindus. When he came to Delhi, he saw a fortress (Lal Kot) which was so marvellous that there was no other fort of height and firmness equal to it in the whole world."[7]

Association with Prithviraj Chauhan - Qila Rai Pithora[]

The term "Qila Rai Pithora" (Persian for "fort of king Prithviraj") was first used by the 16th-century Mughal court historian Abu'l-Fazl in his Ain-i-Akbari. The term is used to denote a fortified complex (including the Qutb Minar complex), where the early rulers of the Delhi Sultanate based themselves.[8]

The texts contemporary or near-contemporary to Prithviraj place him in Ajmer: these texts include Sanskrit-language works such as Prithviraja Vijaya and Kharatara-gachchha-pattavali, as well as the Persian-language chronicles such as Taj al-Masir and Tabaqat-i Nasiri.[9] Later texts such as Prithviraj Raso and Ain-i-Akbari associate him with Delhi in order to present him as an important political figure, because when these texts were written, Delhi had become an important political centre, while Ajmer's political importance had declined.[10]

Although there is no doubt that some of the structures at the site were built before the Delhi Sultanate period, there is no evidence connecting the site to Prithviraj or any other Chahamana ruler. There are no existing records of Prithviraj being crowned in Delhi or even visiting Delhi.[11] As late as in the early 21st century, modern scholars have used the term "Qila Rai Pithora" to denote Delhi's old citadel while referring to the older Persian-language chronicles, although these chronicles themselves do not use the term, instead calling the site simply "Dehli".[12]

Prithviraj's uncle Vigraharaja IV appears to have brought Delhi under Chahamana suzerainty, and Prithviraj may have been an overlord of the contemporary ruler of Delhi. However, there is no concrete evidence that Prithviraj himself lived in Delhi or even visited that city.[13] A short inscription on the Qutb Minar reads Pirathi Nirapa, which some writers read as vernacular for "King Prithvi", but this inscription is undated and its reading is uncertain, thus rendering it flimsy evidence.[14] Some coins, called "Dehliwalas" in the early sources of the Dehli Sultanate, were issued by a series of kings which include the Tomara rulers and a king called "Prithipala". Even if "Prithipala" is assumed to be a name of Prithviraj (although some scholars believe him to be a distinct Tomara king), it is possible that Prithviraja's coins were called "Delhiwalas" not because they were minted in Delhi, but because they were used in Delhi after the city became a major Ghurid garrison.[15]

Other Theories[]

Alexander Cunningham's classified the site into older ("Lal Kot") and newer ("Qila Rai Pithora") parts attributed to the Tomaras and the Chahamanas respectively, but later archaeological excavations have cast doubt on this classification.[11]

Carr Stephen (1876) considered "Lal Kot" only a palace, and used the name "Qila Rai Pithora" to describe the pre-Sultanate fortification at the site. B. R. Mani (1997) referred to the site as "Lal Kot", using the term "Qila Rai Pithora" to describe a fortification wall possibly built by the Chahamanas.[11]

Catherine B. Asher (2000) describes Qila Rai Pithora as Lal Kot enlarged with rubble walls and ramparts. She theorizes that Qila Rai Pithora served as a city, while Lal Kot remained the citadel. Qila Rai Pithora, which was twice as large as the older citadel, had more massive and higher walls, and the combined fort extended to six and a half km.[16]

Asher states that after the Ghurid conquest of the Chahamana kingdom in 1192 CE, the Ghurid governor Qutb al-Din Aibak occupied Qila Rai Pithora, and renamed it to "Dilhi" (modern Delhi), reviving the site's older name.[17] However, Cynthia Talbot (2015) notes that the term "Qila Rai Pithora" first appears in the 16th-century text Ain-i-Akbari, and the older texts use the term "Dehli" to describe the site.[12] Aibak and his successors did not extend or change the fort structure.[17]

See also[]

- Anangpal Tomar II

- Prithviraj Chauhan

- History of Delhi

References[]

- ^ ":: Eight Cities of Delhi ::". www.delhitourism.gov.in. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Tomars of Delhi by Harihar Niwas Dwivedi. Gwalior: Vidyamandir Publications. 1983. pp. 238–239.

- ^ "Explained: The legacy of Tomar king Anangpal II and his connection with Delhi". The Indian Express. 22 March 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "The cities of Delhi: From the legend of Indraprastha to Qila Rai Pithora". Hindustan Times. 22 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

- ^ Tomars of Delhi by Harihar Niwas Dwivedi. Gwalior: Vidyamandir Publications. 1983. p. 264.

- ^ Tomars of Delhi by Harihar Niwas Dwivedi. Gwalior: Vidyamandir Publications. 1983. pp. 295–296.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781107118560.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 73.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 96.

- ^ a b Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 95.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 90.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 97.

- ^ Catherine B. Asher 2000, p. 252.

- ^ a b Catherine B. Asher 2000, p. 253.

Bibliography[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qila Rai Pithora. |

- Catherine B. Asher (2000). "Delhi Walled: Changing Boundaries: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective". In James D. Tracy (ed.). City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

- Forts in Delhi

- Buildings and structures completed in the 12th century

- 12th-century establishments in India

- Archaeological monuments in Delhi

- Archaeological sites in Delhi

- Mehrauli