Saint-Domingue

This article uses bare URLs, which may be threatened by link rot. (August 2021) |

Colony of Saint-Domingue | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1625–1804 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Colony of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Cap-Français (1711–1770) Port-au-Prince (1770–1804) | ||||||||

| Common languages | French, Haitian Creole | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (until 1792) Republic (1792–1804) | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1625–1643 | Louis XIII | ||||||||

• 1643–1715 | Louis XIV | ||||||||

• 1715–1774 | Louis XV | ||||||||

• 1774–1792 | Louis XVI | ||||||||

| Governor General | |||||||||

• 1691–1700 | Jean Du Casse (first) | ||||||||

• 1803–1804 | Jean Jacques Dessalines (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• First French settlement | 1625 | ||||||||

• Recognized | 1697 | ||||||||

| 1 January 1804 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 21,550 km2 (8,320 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Currency | Saint-Domingue livre | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Haiti | ||||||||

| History of Haiti |

|---|

| Pre-Columbian Haiti (before 1492) |

| Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1492–1625) |

| Saint-Domingue (1625–1804) |

| First Empire of Haiti (1804–1806) |

| North Haiti (1806–1820) |

| South Haiti (1806–1820) |

| Republic of Haiti (1820–1849) |

| Second Empire of Haiti (1849–1859) |

| Republic of Haiti (1859–1957) |

| Duvalier dynasty (1957–1986) |

| Anti-Duvalier protest movement |

| Republic of Haiti (1986–present) |

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

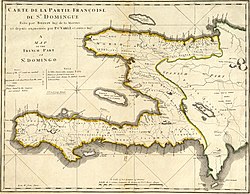

Saint-Domingue (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃.dɔ.mɛ̃ɡ]) was a French colony from 1659 to 1804 on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola; the island that now hosts two countries, the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The name was also used, at times, for the island of Hispaniola as a whole, all of it, nominally, being at times a French colony. The Spanish form of the name, Santo Domingo, also was used at times for the island as a whole. The border between the French-speaking Haiti and the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic was not established until after the Dominican Republic's declaration of independence in 1844.

The French had established themselves on the western portion of the islands of Hispaniola and Tortuga by 1659. In the Treaty of Ryswick of 1697, Spain formally recognized French control of Tortuga Island and the western third of the island of Hispaniola.[1][2]

In 1791, enslaved Africans and some free people of color of Saint-Domingue took part in the Vodou ceremony, Bois Caïman, and planned the rebellion against French authority.[3] The rebels became reconciled to French rule following the abolition of slavery in the colony in 1793, although this alienated the island's dominant slave-owning class. France controlled the entirety of Hispaniola from 1795 to 1802, when a renewed rebellion began. The last French troops withdrew from the western portion of the island in late 1803, and the colony later declared its independence as Haiti, its indigenous name, the following year.

Overview[]

Spain controlled the entire island of Hispaniola from the 1490s until the 17th century, when French pirates began establishing bases on the western side of the island. The official name was La Española, meaning "The Spanish (Island)". It was also called Santo Domingo, after Saint Dominic.[4]

The western part of Hispaniola was neglected by the Spanish authorities, and French buccaneers began to settle first on the island of Tortuga, then on the northwest of Hispaniola. Spain later ceded the entire western coast of the island to France, retaining the rest of the island, including the Guava Valley, today known as the .[4]

The French called their portion of Hispaniola Saint-Domingue, the French equivalent of Santo Domingo. The Spanish colony on Hispaniola remained separate, and eventually became the Dominican Republic, the capital of which is still named Santo Domingo.[4]

Establishment[]

When Christopher Columbus took possession of the island in 1492, he named it Insula Hispana, meaning "the Spanish island" in Latin[5] As Spain conquered new regions on the mainland of the Americas (Spanish Main), its interest in Hispaniola waned, and the colony's population grew slowly. By the early 17th century, the island and its smaller neighbors, notably Tortuga, had become regular stopping points for Caribbean pirates. In 1606, the king of Spain ordered all inhabitants of Hispaniola to move close to Santo Domingo, to avoid interaction with pirates. Rather than secure the island, however, this resulted in French, English and Dutch pirates establishing bases on the now-abandoned north and west coasts of the island.

French buccaneers established a settlement on the island of Tortuga in 1625 before going to Grande Terre (mainland). At first they survived by pirating ships, eating wild cattle and hogs, and selling hides to traders of all nations. Although the Spanish destroyed the buccaneers' settlements several times, on each occasion they returned due to an abundance of natural resources: hardwood trees, wild hogs and cattle, and fresh water. The settlement on Tortuga was officially established in 1659 under the commission of King Louis XIV.

In 1665, French colonization of the islands Hispaniola and Tortuga entailed slavery-based plantation agricultural activity such as growing coffee and cattle farming. It was officially recognized by King Louis XIV. Spain tacitly recognized the French presence in the western third of the island in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick; the Spanish deliberately omitted direct reference to the island from the treaty, but they were never able to reclaim this territory from the French.[6]

The economy of Saint-Domingue became focused on slave-based agricultural plantations. Saint-Domingue's Black population quickly increased. They followed the example of neighboring Caribbean colonies in coercive treatment of the enslaved population. More cattle and slave agricultural holdings, coffee plantations and spice plantations were implemented, as well as fishing, cultivation of cocoa, coconuts, and snuff. Saint-Domingue quickly came to overshadow the previous colony in both wealth and population. Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles," Saint-Domingue became the richest and most prosperous French colony in the West Indies, cementing its status as an important port in the Americas for goods and products flowing to and from France and Europe. Thus, the income and the taxes from slave-based sugar production became a major source of the French budget.

Among the first buccaneers was (1613 – 1676), who played a big part in the settlement of Saint-Domingue. He encouraged the planting of tobacco, which turned a population of buccaneers and freebooters, who had not acquiesced to royal authority until 1660, into a sedentary population. D'Ogeron also attracted many colonists from Martinique and Guadeloupe, including Jean Roy, Jean Hebert and his family, and Guillaume Barre and his family, who were driven out by the land pressure which was generated by the extension of the sugar plantations in those colonies. But in 1670, shortly after Cap-Français (later Cap-Haïtien) had been established, the crisis of tobacco intervened and a great number of places were abandoned. The rows of freebooting grew bigger; plundering raids, like those of Vera Cruz in 1683 or of Campêche in 1686, became increasingly numerous, and Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, elder son of Jean Baptist Colbert and at the time Minister of the Navy, brought back some order by taking a great number of measures, including the creation of plantations of indigo and of cane sugar. The first sugar windmill was built in 1685.

On 22 July 1795, Spain ceded to France the remaining Spanish part of the island of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), in the second Treaty of Basel, ending the War of the Pyrenees. The people of the eastern part of Saint-Domingue (French Santo Domingo)[7][8][9] were opposed to the arrangements and hostile toward the French. The islanders revolted against their new masters and a state of anarchy ensued, leading to more French troops being brought in.

An early death among Europeans was very common due to diseases and conflicts; the French soldiers that Napoleon sent in 1802 to quell the revolt in Saint-Domingue were attacked by yellow fever during the Haitian Revolution, and more than half of the French army died of disease.[10]

Profitable colony[]

Prior to the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the economy of Saint-Domingue gradually expanded, with sugar and, later, coffee becoming important export crops. After the war, which disrupted maritime commerce, the colony underwent rapid expansion. In 1767, it exported 72 million pounds of raw sugar and 51 million pounds of refined sugar, one million pounds of indigo, and two million pounds of cotton.[11] Saint-Domingue became known as the "Pearl of the Antilles" – one of the richest colonies in the world in the 18th-century French empire. It was the greatest jewel in imperial France's mercantile crown. By the 1780s, Saint-Domingue produced about 40 percent of all the sugar and 60 percent of all the coffee consumed in Europe. By 1789, Saint Domingue was made up of about 8,000 plantations ..., producing one-half of all the sugar and coffee that was consumed in Europe and the Americas.[12] This single colony, roughly the size of Hawaiʻi or Belgium, produced more sugar and coffee than all of the British West Indies colonies combined, generating enormous revenue for the French government and enhancing its power.

Between 1681 and 1791 the labor for these plantations was provided by an estimated 790,000 or 860,000 African slaves,[13] accounting in 1783–1791 for a third of the entire Atlantic slave trade.[14] In addition, some Native Americans were enslaved in Louisiana and sent to Saint-Domingue, particularly in the wake of the Natchez revolt.[15] Between 1764 and 1771, the average annual importation of African slaves varied between 10,000 and 15,000; by 1786 it was about 28,000, and from 1787 onward, the colony received more than 30,000 slaves a year.[16] The slave population around 1789 totalled to 406,000 (according to Jacques Pierre Brissot) or 465,000, ruled over by a white population that numbered 28,000 or 31,000.[17][18][19] However, the inability to maintain slave numbers without constant resupply from Africa meant that at all times, a majority of slaves in the colony were African-born, as the brutal conditions of slavery and tropical diseases such as yellow fever prevented the population from experiencing growth through natural increase.[20] African culture thus remained strong among slaves to the end of French rule. The folk religion of Vodou commingled Catholic liturgy and ritual with the beliefs and practices of the Vodun religion of Guinea, Congo and Dahomey.[21] Slave traders scoured the Atlantic coast of Africa, and the slaves who arrived came from hundreds of different tribes, their languages often mutually incomprehensible. While French colonists were hesitant to consider Vodou an authentic religion, perceiving of it instead as superstition, they also promulgated laws against Vodou practices, effectively forcing it underground.[3]

To regularize slavery, in 1685 Louis XIV had enacted the code noir, which accorded certain human rights to slaves and responsibilities to the master, who was obliged to feed, clothe and provide for the general well-being of his slaves. The code noir sanctioned corporal punishment but had provisions intended to regulate the administration of punishments. In any event, such protections were often ignored by white colonists. A passage from Henri Christophe's personal secretary, who lived more than half his life as a slave, describes the punishments the slaves of Saint-Domingue received for disobedience by the French colonists:

Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars? Have they not forced them to consume faeces? And, having flayed them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and poniard?[22]

Thousands of slaves found freedom by fleeing into the mountains, forming communities of maroons and raiding isolated plantations. The most famous was Mackandal, a one-armed slave, originally from the Guinea region of Africa, who escaped in 1751. A Vodou Houngan (priest), he united many of the different maroon bands. For the next six years, he staged successful raids while evading capture by the French. He and his followers reputedly killed more than 6,000 people. He preached a radical vision of destroying white colonization in Saint-Domingue. In 1758, after a failed plot to poison the drinking water of the planters, he was captured and burned alive at the public square in Cap-Français.

Until the mid-18th century, there were efforts made by the French Crown to found a stable French-European population in the colony, a difficult task because there were few European women there. From the 17th century to the mid-18th century, the Crown attempted to remedy this by sending women from France to Saint-Domingue and Martinique to marry the settlers.[23] However, these women where rumoured to be former prostitutes from La Salpêtrière and the settlers complained about the system in 1713, stating that the women sent were not suitable, a complaint that was repeated in 1743.[23] The system was consequently abandoned, and with it the plans for colonisation. In the later half of the 18th century, it was common and accepted that a Frenchman during his stay of a few years would enjoy the sexual services of a black local, and would live with her.[23]

Saint-Domingue had the largest and wealthiest free population of color in the Caribbean; they were known as the gens de couleur. The royal census of 1789 counted roughly 65,000 mestizo.[24] While many free population of color were former slaves, most members of this class were mulattoes, of mixed French/European and African ancestry. Typically, they were the descendants of the enslaved women and French colonists. As in New Orleans, a system of plaçage developed, in which white men had a kind of common-law marriage with slave or free mistresses, and provided for them with a dowry, sometimes freedom, and often education or apprenticeships for their mixed-race children. Some such descendants of planters inherited considerable property. As their numbers grew, they were made subject to discriminatory colonial legislation. Statutes forbade gens de couleur from taking up certain professions, marrying whites, wearing European clothing, carrying swords or firearms in public, or attending social functions where whites were present.[25]

The regulations did not restrict their purchase of land, and many accumulated substantial holdings and became slaveowners. By 1789, they owned one-third of the plantation property and one-quarter of the slaves of Saint-Domingue.[25] Central to the rise of the gens de couleur planter class was the growing importance of coffee, which thrived on the marginal hillside plots to which they were often relegated. The largest concentration of gens de couleur was in the southern peninsula. This was the last region of the colony to be settled, owing to its distance from Atlantic shipping lanes and its formidable terrain, with the highest mountain range in the Caribbean. In the parish of Jérémie, the free population of color formed the majority of the population. Many lived in Port-au-Prince as well, which became an economic center in the South of the island.

End of colonial rule[]

In 1758 white homeowners on Hispaniola began to restrict rights and create laws to exclude mulattoes and Blacks, establishing a rigid class system. There were ten Black people for every white one.

In France, the majority of the Estates General, an advisory body to the King, constituted itself as the National Assembly, made radical changes in French laws, and on 26 August 1789, published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, declaring all men free and equal. The French Revolution shaped the course of the conflict in Saint-Domingue and was at first widely welcomed on the island. At first, wealthy whites saw it as an opportunity to gain independence from France. The elite planters intended to take control of the island and create trade regulations to further their own wealth and power.[26]

Between 1791 and 1804, the leaders François Dominique Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the revolution against the slave system established on the island. The crops harvested by enslaved people in Saint-Domingue and other Caribbean colonies of the French colonial empire were at that time the third-largest source of income to France. Louverture and Dessalines were inspired by the houngans (sorcerers or priests of Haitian Vodou) Dutty Boukman and François Mackandal.

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax from September 1792 to 1795 was the de facto ruler of Saint-Domingue. He was a French Girondist and abolitionist during the French Revolution who controlled 7,000 French troops in Saint-Domingue during part of the Haitian Revolution.[27] His official title was Civil Commissioner. Within a year of his appointment, his powers were considerably expanded by the Committee of Public Safety. Sonthonax believed that Saint-Domingue's whites, most of whom were of Spanish descent, were royalist or separatist conservatives attached to independence or Spain as a way to preserve the slave plantations. He attacked the military power of the white settlers, and by doing so, he alienated the colonists from the French government. Many gens de couleur, mixed-race residents of the colony, asserted that they could form the military backbone of Saint-Domingue if they were given rights, but Sonthonax rejected this view as outdated in the wake of the August 1791 slave uprising. He believed that Saint-Domingue would need ex-slave soldiers among the ranks of the colonial army if it was to survive. Although he did not originally intend to free the enslaved, by October 1793 he ended slavery in order to maintain his own power.[28]

In 1799, the Black military leader Toussaint L'Ouverture brought under French rule a law which abolished slavery and embarked on a program of modernization. He had become master of the whole island.[29]

In November 1799, during the continuing war in Saint-Domingue, Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France. He passed a new constitution declaring that the colonies would be subject to special laws.[30] Although the colonies suspected this meant the re-introduction of slavery, Napoleon began by confirming Toussaint's position and promising to maintain the abolition.[31] He forbade Toussaint to control the formerly Spanish settlement on the east side of Hispaniola, as that would have given the leader a more powerful defensive position.[32] In January 1801, Toussaint and invaded the Spanish settlements, taking possession from the Governor, Don Garcia, with few difficulties.

Toussaint promulgated the Constitution of 1801 on 7 July, officially establishing his authority as governor general "for life" over the entire island of Hispaniola and confirming most of his existing policies. Article 3 of the constitution states: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French."[33]

During this time, Bonaparte met with refugee planters; they urged the restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue, saying it was integral to the colony's profits. He sent an expedition of more than 20,000 men to Saint-Domingue in 1802 to restore French authority.[34]

The French Civil Code of Napoleon affirmed the political and legal equality of all adult men; it established a merit-based society in which individuals advanced in education and employment because of talent rather than birth or social standing. The Civil Code confirmed many of the moderate revolutionary policies of the National Assembly but retracted measures passed by the more radical Convention. The situation of the enslaved and people of mixed race was not improved.

The Haitian Revolution culminated in the elimination of slavery in Saint-Domingue and the founding of the Haitian republic in the whole of Hispaniola. France was weakened by a British naval blockade, and by the unwillingness of Napoleon to send massive reinforcements. Having sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in April 1803, Napoleon began to lose interest in his failing ventures in the Western Hemisphere.

A minority of state officials and civil servants were exempt from manual labor, including some freed colored Haitians. Many slaves had to work hard to survive, and they became increasingly motivated by their hunger. Consisting mostly of slaves, the population was uneducated and largely unskilled. They had lived under authoritarian control as rural laborers. White residents felt the sting most sharply. While Toussaint, a former privileged slave of a tolerant white master, had felt a certain magnanimity toward whites, Dessalines, a former field slave, despised them. A firm hand was used in resistance to slavery.

Napoleon's troops, under the command of his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc, planned to seize control of the island by diplomatic means. They proclaimed peaceful intentions, and kept secret his orders to deport all Black officers.[35][36] Meanwhile, Toussaint was preparing for defense and insuring discipline. This may have contributed to a rebellion against forced labor led by his nephew and top general, Moïse, in October 1801. It was violently repressed, with the result that when the French ships arrived, not all of Saint-Domingue was automatically on Toussaint's side.[37]

For a few months, the island was quiet under Napoleonic rule. But when it became apparent that the French intended to re-establish slavery, because they had done so on Guadeloupe, Dessalines and Pétion switched sides again, in October 1802, and fought against the French.

In late January 1802, while Leclerc sought permission to land at Cap-Français and Christophe held him off, the Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté, effectively quashing the diplomatic option.[38] In November Leclerc died of yellow fever, like much of his army.[39]

His successor, the Vicomte de Rochambeau, fought a brutal campaign. His atrocities helped rally many former French loyalists to the rebel cause. Like other Black slaves captured by the French army, Mackandal was burned alive at the stake. The people of Saint-Domingue, mostly Black, were hostile toward abuse by the French. The slave population had severe food shortages and brutal forced rural labor. The islanders revolted against their new masters and a state of anarchy ensued, bringing more French troops. The people began a series of attacks on the owners of sugar and coffee plantations. French soldiers from Napoleon were sent in 1802 to quell the revolt in Saint-Domingue. They suffered from seasonal epidemics of Yellow fever and more than half of the French army died of disease.[10] The British naval blockade to France persisted.

Dessalines led the rebellion until its completion, when the French forces were finally defeated in 1803.[39] Whites were slaughtered and massacred wholesale under the rule of Dessalines. The brutality toward whites shocked foreign governments.

The last battle of the Haitian Revolution, the Battle of Vertières, occurred on 18 November 1803, near Cap-Haïtien. When the French withdrew, they had only 7,000 troops left to ship to France.

Haiti did not try to support or aid other slave rebellions because they feared that the great powers would take renewed action against them, as happened a few years later with Spain.[original research?] After the defeat of the French army, wealthy white owners saw the opportunity to preserve their political power and plantations. They attacked the town halls that had representatives of the defeated French authority. Elite planters took control of the former Spanish side of the island, asking Spain for a Spanish government and protection by the Spanish army. Later these planters created trade regulations that would further preserve their own wealth and power.[citation needed]

Between 1791 and 1810, more than 25,000 people — planters, poorer whites ("petite blancs"), and free people of color, as well as enslaved people brought with them — fled Saint-Domingue primarily for the United States in 1793, Jamaica in 1798, and Cuba in 1803.[40] Many of them found their way to Louisiana, with the largest wave of refugees, more than 10,000 people — nearly equally divided among whites, free people of color, and enslaved Blacks — arriving in New Orleans between May 1809 and January 1810 after being expelled from Cuba,[41] nearly doubling the population of the city.[42] These refugees had a significant impact on the culture of Louisiana, including developing its sugar industry and cultural institutions.[43]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, American and British authors often referred to Saint-Domingue period as "Santo Domingo" or "San Domingo."[8]:2 This led to confusion with the earlier Spanish colony, and later the contemporary Spanish colony established at Santo Domingo during the colonial period; in particular, in political debates on slavery previous to the American Civil War, "San Domingo" was used to express fears of Southern whites of a slave rebellion breaking out in their own region. Today, the former Spanish possession contemporary with the early period of the French colony corresponds mostly with the Dominican Republic, whose capital is Santo Domingo. The name of Saint-Domingue was changed to Hayti (Haïti) when Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared the independence of all Hispaniola from the French in 1804.[44] Like the name Haiti itself, Saint-Domingue may refer to all of Hispaniola, or the western part in the French colonial period, while the Spanish version Hispaniola or Santo Domingo is often used to refer to the Spanish colonial period or the Dominican nation.

See also[]

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of Haiti

- List of colonial governors of Saint-Domingue

- Spanish Colony of Santo Domingo

Notes[]

- ^ "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Henson, Janine. "Dominican Republic 2014". CardioStart International. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McAlister, Elizabeth (2012). "From Slave Revolt to a Blood Pact with Satan: The Evangelical Rewriting of Haitian History". Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. 41 (2): 187–215. doi:10.1177/0008429812441310. S2CID 145382199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Dominican Republic – The first colony". Country Studies. Library of Congress; Federal Research Division. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ Columbus, Christopher (14 March 1493). "Epistola de Insulis Nuper Repertis" [Letter [to Lord Raphael Sanchez] About Recently Found Isles] (in Latin).

Quam protinus Hispanam dixi

- ^ Rodríguez Demorizi, Emilio (July–September 1954). "Acerca del Tratado de Ryswick" [About the Treaty of Ryswick]. Clío: Órgano de la Academia Dominicana de la Historia (in Spanish). 22 (100): 127–132.

- ^ Von Grafenstein, Johanna (2005). Latin America and the Atlantic World (in English and Spanish). Cologne, Germany: Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. p. 352. ISBN 3-412-26705-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chartrand, René (1996). Napoleon's Overseas Army (3rd ed.). Hong Kong: Reed International Books Ltd. ISBN 085045-900-1.

- ^ White, Ashli (2010). Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8018-9415-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bollet, A.J. (2004). Plagues and Poxes: The Impact of Human History on Epidemic Disease. New York, New York: Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 1-888799-79-X.

- ^ James, C. L. R. (1963) [1938]. The Black Jacobins (2nd ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 45, 55. OCLC 362702.

- ^ Herrmann, Molly M. (2005). The French Colonial Question and the Disintegration of While Supremacy in the Colony of Saint Domingue, 1789–1792 (PDF) (MA). p. 5.

- ^ Coupeau, Steeve (2008). The History of Haiti. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 18–19, 23. ISBN 978-0-313-34089-5.

- ^ Geggus, David Patrick (2009). "The Colony of Saint-Domingue on the Eve of Revolution". In Geggus, David Patrick; Fiering, Norman (eds.). The World of the Haitian Revolution. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-253-22017-2.

- ^ Gayarré, Charles (1854). History of Louisiana: The French Domination. 1. New York, New York: Redfield. p. 448–449.

- ^ Herrmann 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Frostin, Charles (1962). "L'intervention britannique à Saint-Domingue en 1793" [British intervention in Saint-Domingue in 1793]. Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer (in French). 49 (176–177): 299. doi:10.3406/outre.1962.1358.

- ^ Houdaille, Jacques (1973). "Quelques données sur la population de Saint-Domingue au XVIIIe siècle" [Some Data on the population of Saint-Domingue in the 18th Century]. Population (in French). 28 (4–5): 859–872. doi:10.2307/1531260. JSTOR 1531260.

- ^ Arsenault, Natalie; Rose, Christopher (2006). "Africa Enslaved: A Curriculum Unit on Comparative Slave Systems for Grades 9-12" (PDF). University of Texas at Austin. p. 57. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Slavery in the Colonial Era". Africana Online. Archived from the original on 17 June 2006.

- ^ Vodou is a Dahomean word meaning 'god' or 'spirit'.

- ^ Heinl, Robert Debs; Heinl, Nancy Gordon; Heinl, Michael (2005) [1996]. Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1995 (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-3177-0. OCLC 255618073.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Burnard, Trevor; Garrigus, John (2016). The Plantation Machine: Atlantic Capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8122-9301-2.

- ^ Frostin 1962, pp. 293–365.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hunt, Lynn; Censer, Jack, eds. (2001). "Slavery and the Haitian Revolution". Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. George Mason University and American Social History Project. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Weil, Thomas E.; Knippers Black, Jan; Blustein, Howard I.; Johnston, Kathryn T.; McMorris, David S.; Munson, Frederick P. (1985). Haiti: A Country Study. Foreign Area Handbook Series. Washington, D.C.: The American University.

- ^ Stein, Robert (1985). Leger Felicite Sonthonax: The Lost Sentinel of the Republic. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-3218-1.

- ^ Rogozinski, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File Inc. pp. 167–168. ISBN 0-8160-3811-2.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Bell 2007, p. 180.

- ^ Bell 2007, p. 184.

- ^ Bell 2007, p. 186.

- ^ Ogé, Jean-Louis (2002). Toussaint Louverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti [Toussaint Loverture and the Independence of Haiti] (in French). Brossard, Québec: Les Éditions pour Tous. p. 140. ISBN 2-922086-26-7.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 217–22.

- ^ James 1963, pp. 292–294.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 206–209, 226–229, 250.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 232–234.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Slave Rebellion of 1791". Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ Lachance, Paul F. (1988). "The 1809 Immigration of Saint-Domingue Refugees to New Orleans: Reception, Integration and Impact". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 29 (2): 110. JSTOR 4232650.

- ^ Lachance 1988, pp. 110-111.

- ^ Lachance 1988, p. 112.

- ^ Brasseaux, Carl A.; Conrad, Glenn R., eds. (2016). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees 1792-1809. Lafayette, Louisiana: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. ISBN 9781935754602.

- ^ A Brief History of Dessalines from 1825 Missionary Journal Archived 28 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

References[]

- Bell, Madison Smartt (2007). Toussaint Louverture: A Biography. New York, New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 9780375423376.

- Butel, Paul (2002). Histoire des Antilles françaises: XVIIe-XXe siècle [For History]. Collection "Pour l'histoire" (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-01540-6. OCLC 301674023.

- Garrigus, John (2002). Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in Saint-Domingue. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. ISBN 0-230-10837-7. OCLC 690382111.

Further reading[]

- Savary des Brûlons, Jacques (1748). "Saint Domingue". Dictionnaire universel de commerce (in French). Paris: Estienne et fils. hdl:2027/ucm.5317968141.

- Koekkoek, René (2020). The Citizenship Experiment Contesting the Limits of Civic Equality and Participation in the Age of Revolutions (PDF). Studies in the History of Political Thought. Lieden, Netherlands: Brill.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint-Domingue (Haiti). |

External links[]

- The Louverture Project: Saint-Domingue – Saint-Domingue page on Haitian history Wiki.

- The Louverture Project: Slavery in Saint-Domingue

- Saint-Domingue

- French colonization of the Americas

- Former French colonies

- Colonial government in the West Indies

- History of Haiti by period

- History of Hispaniola

- Former colonies in North America

- Former countries in the Caribbean

- States and territories established in 1659

- States and territories disestablished in 1804

- Abolitionism in France

- 17th century in Haiti

- 18th century in Haiti

- 1800s in Haiti

- 1620s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1625 establishments in North America

- 1804 disestablishments in North America

- 1625 establishments in the French colonial empire

- 1804 disestablishments in the French colonial empire