Toba Batak people

A Batak Toba man from Samosir with a hoe over his shoulders, pre-1939. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,672,443 (2013)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

North Sumatra (Toba Samosir Regency, Samosir Regency, Humbang Hasundutan Regency) 3,000,000[citation needed] | |

| Languages | |

| Toba Batak language, Indonesian language | |

| Religion | |

| Protestant Christian (predominantly),[2][3] Catholicism, Islam, Parmalim,[4] Animism (Sipelebegu)[5][6] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Angkola people, Karo people, Mandailing people, Pakpak people, Simalungun people |

Toba people (also referred to as Batak Toba people or often simply "Batak") are the most numerous of the Batak people of North Sumatra, Indonesia, and often considered the classical 'Batak', most likely to willingly self-identify as Batak. The Toba people are found in Toba Samosir Regency, Humbang Hasundutan Regency, Samosir Regency, North Tapanuli Regency, part of Dairi Regency, Central Tapanuli Regency, Sibolga and its surrounding regions.[7] The Batak Toba people speak in the Toba Batak language and are centered on Lake Toba and Samosir Island within the lake. Batak Toba people frequently build in traditional Batak architecture styles which are common on Samosir. Cultural demonstrations, performances and festivities such as Sigale Gale are often held for tourists.

Paleontological research done in Humbang region of the west side of Toba Lake suggests that human activity had existed 6,500 years ago, much earlier than the 800 years existence of King of Batak; and therefore the name "King of Toba" was coined for the early settlers of that region. This discovery also led to the theory of the possibility that the King of Toba could have originated from south India, Indochina (Thailand, Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia and Formosa), South China and so on, even as far as the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.[8]

History[]

Batak kingdoms[]

During the time when the Batak kingdom was based in Bakara, the Sisingamangaraja dynasty of the Batak kingdom divided their kingdom into four regions by the name of Raja Maropat, which are:-[9]

- Raja Maropat Silindung

- Raja Maropat Samosir

- Raja Maropat Humbang

- Raja Maropat Toba

Dutch colonization[]

During the Dutch colonization, the Dutch formed in 1910. The Tapanuli Residency is divided into four regions that is called afdeling (in Dutch language means, section); and today it is known as regency or city, namely:-

- Afdeling Padang Sidempuan, which later became South Tapanuli Regency, Mandailing Natal Regency, Padang Lawas Regency, North Padang Lawas Regency and Padang Sidempuan.

- Afdeling Nias, which later became Nias Regency and South Nias Regency.

- Afdeling Sibolga and Ommnenlanden, today it is Central Tapanuli Regency and Sibolga.

- Afdeling Bataklanden, which later became North Tapanuli Regency, Humbang Hasundutan Regency, Toba Samosir Regency, Samosir Regency, Dairi Regency and Pakpak Bharat Regency.

Japanese occupation[]

During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, the administration of the had little changes.

Post independence of Indonesia[]

After the independence, the government of Indonesia retain Tapanuli as Residency. became the first Tapanuli Resident.

Although there were changes made to the name, but the division of the region was still the same. For example, the name of Afdeling Bataklanden was changed to Luhak Tanah Batak and the first luhak (federated region) appointed was Cornelius Sihombing; who was once also a Demang (chief) Silindung. The title Onderafdeling (in Dutch language means, subdivision) is also changed to urung, and demangs that surpervises onderafdeling are promoted as kepala (head) urung. Onderdistrik (subdistrict) then became urung kecil, and is supervised by kepala urung kecil; which was previously known as assistant demang.

Just as it was in the past, the government of the were divided into four districts, namely:-

Transfer of sovereignty in early 1950[]

During the transfer of sovereignty in early 1950s, the Tapanuli Residency that was unified into North Sumatra province were divided into four new regencies, namely:-

- North Tapanuli Regency (previously known as )

- Central Tapanuli Regency (previously known as )

- South Tapanuli Regency (previously known as )

- Nias Regency

Present[]

In December 2008, the was unified under North Sumatra province. At the moment, Toba is under the Toba Samosir Regency's region with Balige as its capital.

Culture[]

The Toba people practices a distinct culture. It is not a must for Toba people to live in Toba region, although their origin is from Toba. Just as it is with other ethnicities, the Toba people have also migrated to other places to look for better life. For example, majority of the Silindung natives are the Hutabarat, Panggabean, Simorangkir, Hutagalung, Hutapea and Lumbantobing clans. Instead all those six clans are actually descendants of Guru Mangaloksa, one of Raja Hasibuan's sons from Toba region. So it is with the Nasution clan where most of them live in Padangsidimpuan, surely share a common ancestor with their relative, the Siahaan clan in Balige. It is certain that the Toba people as a distinct culture can be found beyond the boundaries of their geographical origins. The region of Toba, known as "the king of Batak" is precisely Sianjur village situated on the slopes of Mount Pusuk Buhit, about 45 minutes drive from Pangururan, the capital of Samosir Regency today.

The Toba clan[]

Surname or family name is part of a Toba person's name, which identifies the family they belong.

The Batak people always have a surname or family name. The surname or family name is obtained from the father's lineage (paternal) which would then be passed on to the offspring continuously.

Pardede, Napitupulu, Panggabean, Siahaan, Sihombing, Siregar, Sitorus, Pandjaitan, Marbun, Lumban Tobing, Aritonang, Pangaribuan, Hutapea,ambarita and Simatupang are popular surnames.

Traditional house[]

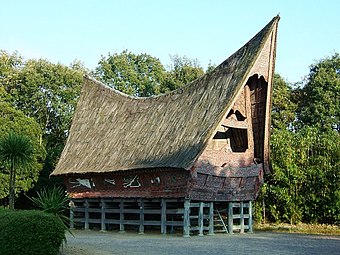

A traditional Toba house.

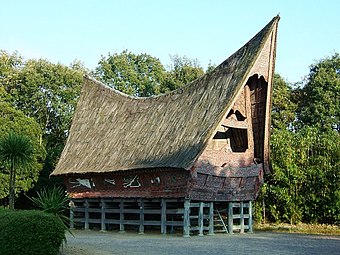

House of a Toba Batak chief.

Giorognom-giorognom (carving at the top of a Toba house) and signa (figurehead on either side of a Toba house)

The traditional house of the Toba people is called Rumah Bolon. It is a rectangular building that can house up to five or six families. One can enter a Rumah Bolon through a staircase in the middle of the house with odd numbers of steps (odd number of staircase means offspring of slave, even number of staircase means offspring of king). When a person enters the house, one must bow in order to avoid one's head from knocking the transverse beam at the entrance of the traditional house. The interpretation of this is that the guests must respect the owner of the house.

Boat[]

Traditional boat of Toba Batak people is called solu, it is a dugout canoe, with boards added on the side bound with iron tacks. They are propelled by sitting rowers, who sit in pairs on cross seats.[10]

Views of Toba people in Indonesian culture[]

The Batak Toba are known throughout Indonesia as capable musicians, and are perceived as confident, outspoken and willing to question authority, expressing differences in order to resolve them through discussion. This outlook on life is contrasted to Javanese people, Indonesia's largest ethnic group, who are more culturally conciliatory and less willing to air differences publicly.[11]

References[]

- ^ Yulianti H, Olivia (2014). "The Study Of 'Batak Toba' Tribe Tradition Wedding Ceremony" (PDF). Politeknik Negeri Sriwijaya. p. 1. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Rahmad Agus Koto (12 December 2013). "Orang Batak Toba yang Saya Kenal". Kompasiana. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ T.O. Ihromi, ed. (1999). Pokok-pokok antropologi budaya. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 169. ISBN 97-946-1252-9.

- ^ Bungaran Antonius Simanjuntak (1994). Konflik Status dan Kekuasaan Orang Batak Toba: Bagian Sejarah batak. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. p. 149. ISBN 60-243-3148-7.

- ^ Jacob Cornelis Vergouwen (2004). Masyarakat dan hukum adat Batak Toba. PT LKiS Pelangi Aksara. p. 75. ISBN 97-933-8142-6.

- ^ Budi Hatees (15 January 2014). Moline (ed.). "Ekspedisi Meraba Sipirok (EMAS) III ke Cagar Alam Dolok Sipirok Hopong, Perkampungan yang Terisolir". Apa Kabar Sidimpuan. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ Jacob Cornelis Vergouwen (2004). Masyarakat Dan Hukum Adat Batak Toba. PT LKiS Pelangi Aksara. ISBN 9-7933-8142-6.

- ^ Farida Denura, ed. (29 October 2016). "Di Humbang, Bukti Sejarah Raja Toba Ada Sejak 5000 Tahun Lalu". Netral News. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ^ Julia Suzanne Byl (2006). Antiphonal Histories: Performing Toba Batak Past and Present. University of Michigan.

- ^ Giglioli (1893). p. 116.

- ^ http://ebooks.iaccp.org/ongoing_themes/chapters/chandra/chandra.php?file=chandra&output=screen

External links[]

- "A Brief Description of The Applying of Dalihan Na Tolu in Batak Toba Society," available on the website of the Repositori Institusi Universitas Sumatera Utara http://repository.usu.ac.id/handle/123456789/16945

Further reading[]

- Bertha T. Pardede; Apul Simbolon; S. M. Pardede (1981), Bahasa Tutur Perhataan Dalam Upacara Adat Batak Toba, Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, OCLC 19860686

- Giglioli, Henry Hillyer (1893). Notes on the Ethnographical Collections Formed by Dr. Elio Modigliani During His Recent Explorations in Central Sumatra and Engano in Intern. Gesellschaft für Ethnographie; Rijksmuseum van Oudheden te Leiden (1893). Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie volume VI. Getty Research Institute. Leiden : P.W.M. Trap.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toba Batak people. |

- Ethnic groups in Indonesia

- Ethnic groups in Sumatra

- History of Sumatra

- Ethnography

- Batak

- Batak ethnic groups