Toltec Empire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

Toltec Empire Altepetl Tollan[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 674 (disputed)[2]–1122 (disputed) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Emblem

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | disputed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tollan-Xicocotitlan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Nahuatl, Itza’, Mixtec, Zapotec, Totonac, Otomi, Pame, Purépecha, others | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Toltec religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tlatoani | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classic/Post Classic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Toltecs arrive at Mam-he-mi, and rename it Tollan | 674 (disputed)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl goes into exile and leaves for Tlapallan | 947 (disputed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Abandonment of Tollan-Xicocotitlan | 1122 (disputed) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Quachtli[citation needed] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the Aztecs, the Toltec Empire,[3] Toltec Kingdom[4] or Altepetl Tollan[1] was a political entity in modern Mexico. It existed through the classic and post-classic periods of Mesoamerican chronology, but gained most of its power in the post-classic. During this time its sphere of influence reached as far away as the Yucatan Peninsula.

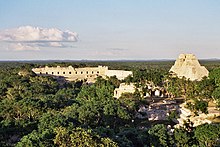

The capital city of this empire was Tollan-Xicocotitlan,[5] while other important cities included Tulancingo[6] and Huapalcalco. More distant cities like Chupícuaro, Chichen Itza, and Coba seem to have been under Toltec control or influence at some point.[citation needed]

History[]

Classic[]

Before Tula[]

Oral traditions about the origin of Toltecs were collected by historians like [7] and Carlos María de Bustamante[8] in the early 19th century. According to said accounts, there was a city named Tlachicatzin in a country ruled by the city of Huehuetlapallan, whose inhabitants called the people of Tlachicatzin "Toltecah", for their fame as dexterous artisans.[7] In 583, led by two notables named Chalcaltzin and Tlacamihtzin, the Toltecah rebelled against their overlords in Huehuetlapallan[8] and after thirteen years of resistance they ended up fleeing Tlachicatzin.[7] Some of the Toltecah later founded a new settlement called Tlapallanconco in 604,[8] but others continued their migration.[9]

These narrations about the origin of the Toltecs have been disputed by archaeologists and historians like Manuel Gamio,[10] [10] and Laurette Séjourné;[11] who had identified the Toltec city of Tollan with Teotihuacan, although this hypothesis has been criticized by many scholars, most notably historian Miguel León-Portilla.[12]

Arrival at Tula and first rulers[]

According to the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, in 674 a large group of Nahuatl-speaking Toltecs arrived at a place called Mam-he-mi (also spelled Manenhi, which in Otomi means Where many people live[12]) which they renamed as Tollan.[2] There they organized a new polity, which at first was ruled as a theocracy, but later was reformed into a monarchy around the year 700[2] (Some authors such as John Bierhorst have translated the Anales de Cuauhtitlan as stating that the Toltecs arrived in Tula in 726 and created their monarchy in 752).[13] Other settlers marched further west, into the territories of the present-day Mexican states of Zacatecas and Nayarit, where they established new cities and polities like Hueyxallan in 610 and Xalisco in 618.[9]

The dynastic history of the Toltecs was recorded by several pre-Columbian and Colonial sources, although there are contradictions in most of them. Some sources say that a man named Huemac,[14] was the leader of the Toltecs when they arrive into Man-he-mi, while others begin the list of Toltec rulers, or tlatoani, with Chalchiutlanetzin,[15] with Mixcoamatzatzin,[14] or even with Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl.[16]

Historians like Alfredo Chavero investigated the numerous proposed lists of Toltec rulers presented in the works of authors like Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl and Juan de Torquemada, and in anonymous sources like the Codex Chimalpopoca. According to Chavero, his research led him to conclude that most of the traditional recounts of the Toltec royalty are not reliable because they were recorded in a style similar to the medieval Chansons de geste,[2] something that became evident once he realised that most of the reigns of the Toltec monarchs lasted 52 years, which is exactly the duration of the 52 year-long cycle of the Mesoamerican calendars,[2] known in nahuatl as Xiuhmolpilli. Therefore, Chavero concluded, that most of the traditional Toltec royal accounts and exploits must be legendary in nature.[2]

According to one of those legends, during the reign of Tecpancaltzin Iztaccaltzin, a Toltec man named Papantzin invented a type of fermented syrup made from the maguey plant. He sent his daughter Xochitl with a bowl of the fermented syrup, today known as pulque, as a gift for the Tlatoani of the Toltecs (in some versions Papantzin would go along with Xochitl). Tecpancaltzin fell in love with the messenger, who kept coming with more bowls of pulque from time to time. After some more visits, the tlatoani granted lands and nobility status to Papantzin, and eventually married Xochitl, who would give birth to a boy named Meconetzin (Child of the Maguey in nahuatl), who became prince of Tollan.[17]

Between 900 and 950,[18] Tollan underwent a major urban redevelopment as the original urban center, today known as Tula Chico (Little Tula), was largely abandoned in favor of a new district, where most of the main religious and political buildings, like the Palacio Quemado (Burnt Palace), were eventually located. This new district is today known as Tula Grande (Great Tula).[19] Also by this time, Tollan had become a magnet for migrants from the surrounding areas, giving the city a large and ethnically diverse population, with the Nonoalca and Chichimeca Toltecs being the most important groups in the city.[16]

Reign of Quetzalcoatl[]

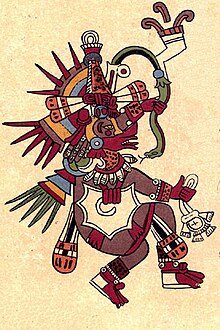

According to the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, the city of Tollan-Xicocotitlan was ruled by the priest-king Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl from 923 to 947.[14] This ruler was born in the year 895[20][4] at Michatlauhco, a place which according to Mexican archaeologist could be located near the present-day town of Tepoztlán, in the Mexican state of Morelos.[21]

Quetzalcoatl was regarded as a wise and benevolent ruler, who made Tollan a "prosperous city in which their inhabitants -the Toltecs- were endowed with great qualities".[22] At the same time he was regarded as a holy and pious man, who engaged regularly in acts of penance.[22] Cē Ācatl Topiltzin preached against the practice of human sacrifices, arguing that the supreme deity whose name he took for himself wasn't pleased with the practice of ritual killings.[23]

According to Bernardino de Sahagún,[24] one day, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl was visited by an elderly man (said to be Tezcatlipoca in disguise[22]) who offered him a "medicine" that would make him younger. This medicine was just a bowl of pulque, and after tasting it, the king invited his sister, the priestess Quetzalpetlatl, to drink with him, with both getting drunk soon after.[25] Because of their drunkenness, both siblings forgot their sacred duties and acted disgracefully,[22] damaging their reputations. After this humiliation, Quetzalcoatl left Tollan in 947, and traveled to the east, to the mythical land of Tlapallan, which according to tradition was located on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.[20] There, Quetzalcoatl took a canoe and immolated himself.[22]

Internal conflicts and settlement in Yucatan[]

Some authors, like Mexican historian Vicente Riva Palacio, argue that Quetzalcoatl died earlier, in 931; and that said event would trigger political instability in Tollan, eventually leading to an important migration of Toltecs to other parts of Mesoamerica around 981, especially to the Yucatan Peninsula, where they would mainly settle at the city of Uxmal.[26] Regardless of the exact date of Quetzalcoatl's death, traditional accounts indicate that at the end of the 10th century, a religious war broke between members of the cult of Tezcatlipoca and supporters of Quetzalcoatl.[4][27] The adherents of Quetzalcoatl didn't favour large-scale human sacrifices, which were largely suppressed by Ce Acatl Topiltzin during his reign, while the adherents of Tezcatlipoca regarded them as an essential part of their religion.[4] Also, the supporters of Quetzalcoatl and his reforms were mostly of Nonoalca background while the supporters of the cult of Tezcatlipoca were mostly of Chichimeca background.[27]

According to Diego Durán, the conflict was brief, but eventually a second war between the two groups broke out.[4] This war lasted from 1046 to 1110, and ended with the defeat of the followers of Quetzalcoatl.[4] Because of the violence, many of those who supported Ce Acatl Topiltzin fled Tollan, with a sizeable portion of these exiles heading towards the Maya cultural area. According to Mexican archaeologist , the cult of Quetzalcoatl (known as Kukulkan in Yucatan) was introduced in the region by the Itza around 987 AD.[28] The Itza were a group of mixed Putún Maya and Toltec descent, which had welcomed immigrants from Tollan time moving into the Yucatán Peninsula, and had adopted the religious teachings of the Toltecs.[28]

As they traveled southwards, some followers of Ce Acatl Topiltzin seem to have followed his example and adopted the name "Quetzalcoatl" and its Maya equivalents, "Kukulkan" and "Q'uq'umatz", for themselves.[29][30] According to Mexican historian Miguel León-Portilla, these new "Quetzalcoatl" leaders often led their own followers into military actions against the Mayan peoples.[29] The exploits of these personages had become source of misunderstandings and confusion for researchers over centuries, as they are often confused with Ce Acatl Topiltzin himself.[30]

Post-Classic[]

Collapse of Tula and Toltec diaspora[]

The ethno-religious conflicts between the Nonoalca and the Chichimeca, along with the great famine that affected Tollan between 1070 and 1077,[4] led to a series of important migrations from Tollan to other parts of Mesoamerica in the late 11th century and early 12th century.[27] One of these groups of Toltec exiles eventually took over the city of Cholula, in the present-day Mexican state of Puebla, around 1200[31]

According to Durán, in 1115, tribes from the north (probably Chichimecas, Otomi[4] or Huastecs[27]) attacked the domains of Tollan. After a series of brutal battles at the villages of and , in which both sides took and sacrificed numerous prisoners, the Toltecs were defeated in 1116.[4] After this defeat, Huemac, the priest-king of Tollan, abandoned the city along with other Toltecs[23] and headed south, to the city of Xaltocan, in the Valley of Mexico.[4] Soon, the king would be abandoned by his closest followers, who chose a man called as their leader;[4] while the majority of the Toltecs would split in smaller groups and begin their diaspora across Mesoamerica.[27][23]

In 1122, shortly after being betrayed by his followers, Huemac hanged himself in Chapultepec,[23][4] and by 1150,[18] Tula was virtually abandoned. Some Toltecs would remain around the ruins of their former capital, where they would be under the rule of Culhuacán, a nearby city-state.[27] After the fall and abandonment of Tollan in the 12th century, the former Toltec dominions would be ruled by numerous smaller city-states, which are known as altepetl in nahuatl, most of which would be ruled by descendants (both real and self-proclaimed) of the Toltec nobility.[27] Toltec heritage became the standard of the nobility in most of Mesoamerica. Because of this, many rulers of later kingdoms and empires would claim Toltec lineage as a way to legitimize their power,[29] including the Aztec emperors, the Mixtec kings in Oaxaca, and the K'iche' and Kakchiquel rulers in Guatemala.[32]

Rulers[]

List of rulers[]

Pre-Columbian and Colonial documents describe the Toltec rulers, but most of those accounts are legendary in nature, and therefore not historically reliable.[2] Some lists include figures such as Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl and queen Xochitl as rulers, but most of them omit them.

According to Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, these would be the Toltec rulers:[15]

| Name | Reign | Lifespan | Family |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chalchiuhtlanetzin | 510-562 | ||

| Ixtlilcuechahauac | 562-614 | ||

| Huetzin | 614-666 | ||

| Totepeuh | 666-718 | ||

| Nacaxoc | 718-770 | ||

| Tlacomihua | 770-826 | ||

| Xihuiquenitzin | 826-830 | ||

| Tecpancaltzin Iztaccaltzin | 830-875 | ?-911 |

|

| Meconetzin | 875-927 | ||

| Mitl | 927-979 | ||

| Xiuhtlaltzin | 979-983 | ||

| Tecpancaltzin | 983–1031 | ||

| Topiltzin | 1031–1063 |

According to Francisco Javier Clavijero,[15] these would be the rulers of Tollan:

| Name | Reign |

|---|---|

| Chalchiuhtlanetzin | 667-719 |

| Ixtlilcuechahauac | 719-771 |

| Huetzin | 771-823 |

| Totepeuh | 823-875 |

| Nacaxoc | 875-927 |

| Mitl | 927-979 |

| Xiuhtlaltzin | 979-983 |

| Interregnum | 983-1031 |

| Topiltzin | 1031–1063 |

According to the Anales de Cuauhtitlan,[14] the Toltec sovereigns would be:

| Name | Reign |

|---|---|

| Mixcoamatzatzin | ca.700-ca.765 [2] |

| Huetzin | ca.896 |

| Totepeuh | ca.887 |

| Ilhuitimal | 887–923 |

| Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl | 923–947 |

| Matlacxochitl | 947–983 |

| Nauhyotzin | 983–997 |

| Matlaccoatzin | 997-1025 |

| Tlilcoatzin | 1025-1046 |

| Huemac | 1047–1122 |

- All dates are AD

Government[]

Governors of the various Toltec regions were taken from the ranks of the nobles.[citation needed] They took part in the councils convened on the death of each king to determine the fitness of candidates hoping to be named heir. This was a usual Mesoamerican pattern in the historical era of the Toltec, one adopted by the Aztec and later cultures.[citation needed] These same aristocrats would also have been instrumental in the collection of tribute from the vassal or allied cities and regions. Such tribute was a hallmark of the Toltec Empire, providing increased economic stability. The tribute received from other groups was distributed as part of the wealth of the Toltec upper classes or provided to those in need in the lower ranks of society. Some tribute, however, was set aside as a resource to be utilized in the vast Toltec trade enterprises.[citation needed]

Society[]

Commoners[]

Because agriculture was basic to the Toltec economy, the farmers, although far removed in status from the aristocracy, were in the majority and were secure in their rights and privileges. Tula, the Toltec capital, held a diverse population throughout the Toltec era. Commoners in the capital would have come from other cultures and from allied or vassal states.[citation needed]

Upper classes[]

Artists and craftsmen were especially valued and were a special force within the Toltec government, as were the merchants. Toltec priests and warriors made up the other castes in Toltec society. Generally the aristocratic ranks of the Mesoamerican cultures held the commanding positions, but within the priestly and warrior groups certain commoners, especially those who demonstrated courage, wisdom, intellect and the ability to lead, might advance to certain levels of power. Restrictions were enforced within the Toltec government to ensure that commoners did not advance beyond a certain point, but worthy candidates for less powerful offices were drawn from all ranks..[citation needed]

Slavery[]

The status of slaves in the Toltec world is not documented. It is known, however, that the Huastec and others were carried weeping into Tula, possibly as victims for sacrificial ceremonies or as doomed chattel.[33]

Art[]

There are many types of Toltec art, mainly sculptures, paintings, figurines, and precious items made of jade, gold, turquoise, and other valuable materials.[citation needed]

Architecture[]

At its height Tula may have had a population as high as 85,000 (60,000 in the city and another 25,000 in the area).[citation needed] It was much smaller than classic cities such as Teotihuacan and Tikal, or later cities such as Tenochtitlan and Cholula, although at the time it may have been the largest city in Mesoamerica.[citation needed]

Most inhabitants of Tula lived in large apartment complexes. Others lived in palaces and group homes. People from different areas and of different classes lived separately, in distinct neighborhoods. Although Chichen Itza is far from Tula, Toltec influence is obvious on buildings such as the pyramid of Kukulkan and the market.[citation needed]

Most of Tula was set up in a grid plan. The buildings were made of stone with an adobe finish. The Atlantes of Tula are representations of the god Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli in warrior attire which were used as columns to hold up the roof of the great room in the god's temple.[34] This use of statues as columns is a distinctive feature in Toltec architecture. Outside of Chichen Itza the Toltecs had little influence on the architecture in Yucatan.[citation needed]

Sculpture[]

Some of the most famous Toltec sculptures are the Atlanteans of Tula. These monoliths measure just over 4.5 meters high. They are carved in stone basalt, and are representations of the Toltec god Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli in warrior attire. They are clothed in butterfly breastplates. Their weapons are atlatls, darts, knives of flint, and curved weapon that are characteristic of the warrior representations in the Toltec culture.[34]

The monumental Atlanteans are at the top of the Temple Tlahuizcalpantecutli also called "Morning Star" from which all the main plaza is seen, these sculptures are characterized by their large size (an example of the skill the Toltecs had for working with stone).

The Toltecs also made many smaller ceramic and stone figurines.[citation needed]

Chac Mools[]

Chac mools are reclining figures with their heads facing 90 degrees from the front, leaning on their elbows and holding a bowl or a disk on their chest.[35]

Chac mools were first made in the Tula area in the 9th century, as Toltec power and influence grew chac mools began to be made in other areas such as Michoacán and Yucatan. Despite the decline in Toltec culture Chac mools continued to spread as far away as Costa Rica in approximately 1000 CE.[36]

Valuables[]

The toltecs made many pieces of jewelry such as earplugs and nose rings. Much of these fine masks were made of gold, turquoise and most of all jade.[citation needed]

International relations[]

Totonacapan[]

Totonacapan was the name of a kingdom in Veracruz. In the late 9th or early 10th century, (probably during the reign of Ce Acatl Topiltzin) the Toltecs invaded Totonacapan. They conquered most of the Totonac area including El Tajin. Many of the Totonacs fled as refugees to Cempoala. Records of this are obscure but from what is known Cempoala was never conquered.[citation needed]

The Toltecs founded colonies in Veracruz.[33]

Maya region[]

Chichen Itza[]

One of the most controversial topics involving the Toltecs is what their relationship with Chichen Itza was. The similarities between the two cities has raised several hypotheses about the nature of the links between the two, although none of them have the full support of the specialists in the field. In the 19th century, French archaeologist Désiré Charnay was the first person who pointed out that the main plazas of Tula and Chichen Itza were similar, a fact that led him to postulate that the city could have been conquered by Toltecs led by Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, who Charnay referred as Kukulkan.[37] This hypothesis was defended in the 20th century by Herbert Joseph Spinden, an art historian who became obsessed with the idea and often used pseudo-historical sources to back his claim about a conquest of the Itza Maya by Quetzalcoatl.[38]

The conquest hypothesis of Charnay and Spinden has been largely abandoned in modern archaeology as more evidence suggests that instead of a conquest of Chichen Itza by the Toltecs, the Itza people had already embraced Toltec teachings before moving to Yucatan;[28] also, according to Mexican historian Miguel León-Portilla, many of the references to leaders with the name "Quetzalcoatl", "Kukulkan" or "Q'uq'umatz" in the Maya sources may not even refer to Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl himself, but to some of his followers and their disciples who also took the name of the Feathered Serpent deity for themselves.[29][30]

Rest of Yucatan[]

Chichen Itza would eventually become the largest city in Yucatan with a population of at least 50,000 people.[39] Almost as many people as lived in Coba during the classic period.[40]

In the mid 8th century,[41] the Classic Maya civilization began to collapse. Around 925, about the same the time in which the Toltecs began to migrate to the Maya area, most of the major Maya cities in the Yucatán Peninsula had already been abandoned due to food shortages and peasant revolts[42] Some Maya cities in the Yucatan peninsula at the time were:

- Uxmal

- Jaina (a small city on an island in marshland on the coast of the gulf of Mexico)

- Xtampak

- Izamal

- Dzibilchaltun

- Edzna

- Calakmul

- Sayil

- Kabah

- Muyil

- Zama

- Mayapan

- Ek' Balam (capitol of the Kingdom of Talol[43])

La Quemada[]

Toltec control and influence expanded much further north than that of the Mexica. One of the northernmost cities believed to be Toltec is La Quemada. La Quemada was first built around 300 CE. Between 350 and 700, it had extensive trade with Teotihuacan[citation needed]. La Quemada was abandoned after the fall of Tula in 1222.[citation needed] It was burned down, hence the name La Quemada (Quemada being Spanish for burned).

Chupícuaro[]

The Chupícuaro culture was important due to the influence it had in the area. It is possible it spread to southern United States around 500 BCE. There are theories that the first Guanajuato inhabitants belonged to this culture.[44]

The city of Chupícuaro was inhabited between 800 BCE and 1200 CE. Chupícuaro developed in a vast territory in, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Guerrero, Mexico State, Hidalgo, Colima, Nayarit, Querétaro and Zacatecas.

Chupícuaro was influenced by the Toltecs between c. 900 and c. 1200.[citation needed]

Warfare[]

The Toltecs elevated warfare into a religious and state-controlled status in the region, which reached its peak with the Mexica military power in the centuries following the fall of Tula. Militarism was a vital aspect of the Toltec Empire, one that carried distinction and honor and endowed an entire class of warriors. The Atlanteans of Tula are adorned with symbols of Quetzalcoatl distinguishing them as servants of the nation. The Toltec warriors adopted Huitzilopochtli, the Nahua god of war, as a patron after Ce Acatl Topiltzin left Tula.[citation needed]

The Toltec were skilled in battle, ferocious and highly trained. A standing army, garrisons, forts and reserve units comprised a formidable weapon against inhabitants of regions coveted by the Toltec and against enemies. Because of their skill and their bravery in battle, the Toltec were able to instill enough awe and respect among their neighbors that cities such as Tula could be built without heavy defenses incorporated into their design. Coyote, Jaguar, and eagle were some of the higher ranks of the Toltec military.[45]

The upper ranks of the Toltec army wore cotton armor, heavily padded to deflect enemy, arrows and spears, with breastplates, in the form of coyotes, jaguars or eagles if the warrior belonged to the order of one of these animal totems. A round shield was carried into battle, and the swords were fastened with belts. A short kilt protected the lower half of the torso, and the legs and ankles were covered with sandals and straps. Quetzal plumes decorated warriors' helmets, and skins, plumage and other materials probably were used as emblems of the particular god or order that they served. The fact that the warriors depicted wore nose ornaments indicates that they were of noble rank. Some of the warriors wore beards.[46]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ce-Acatl: Revista de la cultura Anáhuac (1991)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Chavero, A. (Ed.) (1892) Obras Históricas

- ^ Palerm, A. (1997) Introducción a la teoría etnológica. Universidad Iberoamericana [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Durán, D. Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de Tierra Firme [2]

- ^ Cobean, R.H., Jimenez, G.E. & Mastache, A.G. (2016) Tula. Fondo de Cultura Economica [3]

- ^ Tulancingo de Bravo. Enciclopedia de los Municipios y Delegaciones de México. [4]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Veytia, M. (1836) Historia antigua de Méjico. Vol. 1

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bustamante, C.M. (1835) Mañanas de la Alameda de México: Publícalas para facilitar á las señoritas el estudio de la historia de su país. Vol. 1. [5]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Agraz G.A.G. (1958) Jalisco y sus hombres: compendio de geografía, historia y biografía jaliscienses [6]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Florescano, E. (1963) Tula-Teotihuacán, Quetzalcóatl y la Toltecayótl. Historia Mexicana. vol. 13 (2)

- ^ Séjourné, L. (1994) Teotihuacan, capital de los Toltecas. Siglo XXI

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leon-Portilla, M. (2008) Tula Xicocotitlan: Historia y Arqueologia

- ^ John Bierhorst's History and Mythology of the Aztecs: The Codex Chimalpopoca, pgs 25-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Adams, R.E.W.(2005) Prehistoric Mesoamerica. University of Oklahoma Press [7]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bernal, I., Ekholm, G.F. & Wauchope, R. (1971) Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volumes 10 and 11: Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica [8]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Tula y los Toltecas

- ^ Remolina, L.M.T. (2004) Leyendas de la provincia mexicana: Zona Altiplano [9]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fash, W.L., & Lyons, M.E. (2005) The Ancient American World. Oxford University Press [10]

- ^ Kristan-Graham, C. (2007) Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Dumbarton Oaks [11]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Apendice-Explicacion del Codice Geroglifico de Mr. Aubin de Historia de las Indias de la Nueva España y Islas de Tierra Firme. Diego Duran & Alfredo Chavero Vol II 1880 p 70

- ^ Dubernard, C.J. ¿Quetzalcoatl en Amatlán (Morelos)?

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Olivier, G. (2012) Los dioses ebrios del México antiguo. De la transgresión a la inmortalidad. Arqueología Mexicana

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d León-Portilla, M. (2003) En torno a la historia de Mesoamérica. UNAM [12]

- ^ Sahagún, B. (ca. 1540) Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España [13]

- ^ Navarrete, L.F. & Olivier, G. (2000)El héroe entre el mito y la historia [14]

- ^ Riva, P.V. (1884) México a través de los siglos: Historia antigua y de la conquista [15]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Knight, A. (2002) Mexico: Volume 1, From the Beginning to the Spanish Conquest. Cambridge University Press [16]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Piña-Chan. R (2016) Chichén Itzá: La ciudad de los brujos del agua. Fondo de Cultura Economica [17]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d León-Portilla, M. (2002) América Latina en la época colonial. Grupo Planeta [18]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rodriguez, A.M. (2008) Los toltecas influyeron en la cultura maya: León-Portilla. La Jornada [19]

- ^ Evans, S.T. (2001) Archaeology of ancient Mexico and Central America, an Encyclopedia. Garland Publishing, Inc

- ^ León-Portilla, M. (2016) Toltecáyotl: Aspectos de la cultura náhuatl. Fondo de Cultura Economica [20]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-25. Retrieved 2014-07-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martínez del Río, Pablo y Acosta, Jorge R. (1957) Tula: guía oficial. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. 54 páginas

- ^ "MillerTaube93-03,p60"

- ^ Solano 26 February 2012.

- ^ Charnay, D. (1885) La Civilisation Tolteque. Revue d'Ethnographie. vol. 4

- ^ Spinden, H.J. (1913)A Study of Maya Art, Its Subject Matter and Historical Development. Courier Corporation [21]

- ^ HiddenCancun.com. "Chichen Itza - Mayan Ruins - Yucatan". Hiddencancun.com. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Coba's Maya Ruins - Yucatan, Mexico - Have Camera Will Travel". Havecamerawilltravel.com. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Demarest, A.A. & Rice, D.S. (2005) The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation. University Press of Colorado

- ^ Bley, B. (2011) The Ancient Maya and Their City of Tulum: Uncovering the Mysteries of an Ancient Civilization and Their City of Grandeur [22]

- ^ Braswell, G.E. (2014) The Ancient Maya of Mexico: Reinterpreting the Past of the Northern Maya Lowlands [23]

- ^ "Historia prehispánica" [Prehispanic History]. León-Gto. Retrieved October 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-25. Retrieved 2014-07-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ [24]

- Toltec history

- Mesoamerican cultures

- Pre-Columbian cultures of Mexico

- Former empires in the Americas

- Former monarchies of North America

- Former confederations

- Mesoamerica

- States and territories established in the 490s

- 496 establishments

- 1122 disestablishments

- 12th-century disestablishments in North America

- States and territories disestablished in the 1120s

- Former countries in North America