U.S. Route 66 in Illinois

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Will Rogers Highway Main Street of America | ||||

Route 66 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by IDOT | ||||

| Length | 301 mi (484 km) | |||

| Existed | November 11, 1926–June 25, 1974[1] | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| West end | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

U.S. Route 66 (US 66, Route 66) was a United States Numbered Highway in Illinois that connected St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois. The historic Route 66, the Mother Road or Main Street of America, took long distance automobile travelers from Chicago to Southern California. The highway had previously been Illinois Route 4 (IL 4) and the road has now been largely replaced with Interstate 55 (I-55). Parts of the road still carry traffic and six separate portions of the roadbed have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

History[]

When US 66—first known as the Main Street of America and later dubbed the Mother Road by novelist John Steinbeck in 1939—was designated on November 11, 1926, the original path used mostly pre-existing roads. That was intentional, to minimize any needed construction and to get the entire path of the route open to traffic as soon as possible. In fact, because Illinois had already paved most of the roads that would comprise US 66, Illinois was the first of the eight states through which the route ran to have its segment of US 66 completed at a time when much of Route 66 was still a gravel-and-dirt road.[2][3]

In Illinois and the Midwest in general, the construction of US 66 was important to the economies of small, rural towns, which saw a burst of activity when the road finally passed through.[4] However, those communities in Illinois were already profiting from a paved highway that preceded Route 66 by a few years. In 1916, the Federal Aid Post Road Act, known as the Shackleford Bill, passed Congress and appropriated $75 million to be distributed to the states over the next five years. Funding was provided on an ongoing basis, over the period of five years, and the law made the federal government an active partner in road building for the first time.[4] Five roads in Illinois were designated to receive federal money under the legislation; they were: the National Old Trails Road (National Road, present-day US 40), Lincoln Highway, Dixie Highway, the road from Chicago to Waukegan, and the road from Chicago to East St. Louis, including portions of IL 4, which was the actual predecessor to US 66 in Illinois.[4]

The earliest known Chicago-to-St. Louis road was a former Native American Indian trail and stagecoach road that was renamed the Pontiac Trail in 1915. Route 66 began in Chicago and, once outside the metropolitan Chicago area, traveled down the Pontiac Trail through many cities and towns on its way southwest, including Joliet, Odell, Bloomington, Lincoln, Springfield, Edwardsville and East St. Louis.[4]

IL 4 coincided with most of the Pontiac Trail and closely paralleled the Chicago and Alton Railroad tracks running from Chicago to East St. Louis. The roadbed for IL 4 was prepared in 1922 by teams of horses dragging equipment behind them. Laborers received 40 cents per hour for performing backbreaking labor on the roadbed.[4] In 1923 in Bloomington-Normal, concrete was poured along the road's path along much the same route US 66 would take on its original route through the area. By 1924, IL 4 was almost entirely paved between Chicago and St. Louis.[4] Construction on the few remaining parts of US 66 in Illinois began in 1926.

By the 1930s, US 66 extended from Chicago through Springfield to St. Louis; much of the original pavement was still in use by the early 1940. The dangers of the original pavement were recognized by the nickname "Bloody 66," which reflected the frequently deadly road accidents along the mostly rural route. When World War II erupted, Route 66—already the heaviest trafficked highway in Illinois—saw an increase in military traffic and importance to defense strategy. The aging road's deterioration was hastened by the increase in military truck traffic. The Defense Highway Act of 1941 provided Illinois with about $400,000 in funding, and by 1942, plans were in place to make much needed road repairs that were also intended in part to make the road safer for traffic.[5]

Route description[]

St. Louis to Hamel[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2011) |

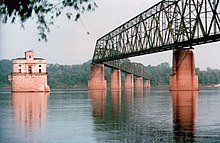

Entering Illinois from St. Louis, Missouri, the highway originally crossed the Mississippi River at the McKinley Bridge. This first alignment passed through Venice and Madison, eventually becoming IL 203 in northeast Granite City. In 1930, the Chain of Rocks Bridge was opened on Bypass US 66, allowing travelers to circumvent St. Louis. This route met the original Route 66 in Mitchell. The Luna Cafe, Bel-Air Drive-In sign, and the Old Greenway Motel can be found along this stretch of road, as well as The Mustang Corral, a Ford Mustang shop, just before IL 157 on the right hand side eastbound. Route 66 joined IL 157 through Hamel via Edwardsville.

Congestion at the McKinley Bridge was reduced in 1951 with the construction of the Veterans' Memorial Bridge. Route 66 joined US 40, traversing East St. Louis and Fairmont City. Shortly after Fairmont City, Route 66 passed Cahokia Mounds, later a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It joined IL 157 on the western end of Collinsville, later navigating to modern day I-55 via IL 159. This stretch of Route 66 met the main route in Hamel.

Poplar Street Bridge was opened in 1967 to facilitate I-55, I-64, and I-70. US 66 and US 40 were both simultaneously rerouted over this newer bridge instead of the Veterans' Memorial Bridge.

Hamel to Springfield[]

Original route[]

U.S. Route 66 originally followed IL 4 north of Hamel. This alignment navigated through Staunton, Sawyerville, Benld, Gillespie and Carlinville to Nilwood. The section of US 66/IL 4 from Nilwood to Girard was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 23, 2002.[6] Route 66 continues along IL 4 north through Virden, Thayer, to Auburn. A section of IL 4 north of Auburn and south of Springfield, which was also part of the original span of US 66, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 6, 1998.[6] This is the last brick alignment in Illinois. Route 66 then passed through Chatham, and entered Springfield. Breaking off of IL 4, the route passed the Illinois State Capitol and the Old State Capitol.

Eastern alternate route[]

An alternate route northward from Hamel was opened in 1930. It followed IL 4 for three miles (4.8 km), then branched off to the east, bypassing Staunton. The road moved northeast through Mount Olive past the Soulsby Service Station. The alignment from Litchfield to Mount Olive was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 29, 2001.[6] This segment is a 9.35-mile (15.05 km) stretch that begins northwest of Mount Olive in southeastern Macoupin County and ends about one mile (1.6 km) north of the intersection of US 66 and IL 16 in Litchfield. This alignment passed through North Litchfield, South Litchfield, Cahokia and Mount Olive townships. The terrain through the area is mostly flat. Unlike other sections of Route 66 in Illinois that are listed on the National Register, the segment from Litchfield to Mount Olive does not include any contributing structures such as bridges or culverts.[7] The Ariston Café in Litchfield is the longest-operating restaurant along the former US 66. The Belvidere Café, Motel, and Gas Station also provided services to travelers. This alternate alignment continued north past Waggoner, Farmersville, Divernon, Glenarm and joined the original path in Springfield near the Old Capitol Building.

The increased military traffic along US 66 during World War II and the consequent extreme demands put on the road bed caused parts of the road to be replaced along this stretch during the 1940s. This stretch of US 66 became a four-lane road with two lanes in each direction; the new lanes became the southbound lanes. For 2.15 miles (3.46 km) south of Litchfield, the southbound lanes still carry two-way traffic.[7] A new alignment of Route 66 headed northeast of Hamel through Livingston. This new section bypassed Mount Olive to the northeast, later running west of the old route through Litchfield before rejoining the original path. Sections of the older alternate route were destroyed during the 1930s when Lake Springfield was created; the fragments of the old route that remain were added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 12, 2009.

Springfield to Gardner[]

From Springfield to Gardner, Historic US 66 is now a parallel frontage road for I-55, except for business loops for Lincoln and Bloomington-Normal. US 66 originally continued north through Springfield past the Illinois State Fairgrounds and the Lazy A Motel. The route rejoined IL 4 and continued alongside Carpenter Park; a small section of this route is listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 9, 2002.[6] Route 66 continued north through Sherman and Broadwell, entering Lincoln. From there, the route veered northeast through the towns of Lawndale, Atlanta, McLean, Funk's Grove, and Shirley. McLean is home to the famous Dixie Travel Plaza, a truck stop that was established as the Dixie Truckers Home in 1928.[8] To the north is Funks Grove, settled by the Funk family in 1824 where pure "maple sirup"[a] is made.

From there, Route 66 entered Bloomington, passing through the Central Business District and the McLean County Square. Further north as Bloomington gave way to Normal, the route passed Illinois State Normal University. From Normal, Route 66 continued northeast through Towanda, where there is now a parkway and bike trail along a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) stretch of the abandoned highway, with exhibits that highlight all eight states through which Route 66 travels. There are also classic "Burma Shave" signs displayed along the trail.[8]

Route 66 traveled through Lexington and Chenoa to Pontiac. Passing by the Illinois State Police Office, the route continued northeast through Cayuga and Odell to Dwight. A restored Standard Oil Gasoline Station still stands in Odell, as does Ambler's Texaco Gas Station in Dwight.

The 18.2-mile (29.3 km) stretch from Cayuga to Chenoa was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 23, 2007.[6] This section of US 66 was commissioned in 1926. The road segment travels from the northeast to the southwest and begins in the southeast corner of Odell Township in Livingston County and ends in the northwest corner of Chenoa Township in McLean County. US 66 passes through Odell, Esmen, Pontiac, Eppards Point, and Pike Townships, on its stretch from Cayuga to Chenoa. The road is paralleled on its east by the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and on its west by I-55.[5] Portions of the northbound and southbound lanes still carry traffic; in spots where one of the sections is still in use the other section is abandoned but still extant.[5]

Along this stretch of highway, there are 14 structures and buildings. Insofar as the National Register and historic preservation are concerned, eight of those are considered contributing structures to the listing and six are considered non-contributing. There are also 12 highway bridges found along the segment and a box culvert; six of the bridges are considered contributing to the National Register listing, as is the box culvert. Six of the bridges have been replaced since the historic period, and all of the bridges are constructed from concrete. The bridges have various lengths and support structure. The box culvert along the segment of road measures 15 feet (4.6 m) by 6 inches (15 cm) wide and was built as part of the road's foundation. This particular box culvert, like many, usually went unnoticed by travelers along the road.[5] The section of pavement between Pontiac and Cayuga was part of a larger section of the roadway that began north of Cayuga in Gardner. This entire section was built in 1943 after large parts of Route 66 became badly deteriorated during the mid-1940s. The portion of the roadway that extended 27 miles (43 km) south of Pontiac to the newly constructed bypass at Bloomington-Normal was constructed during the early 1940s.[5]

Gardner to Welco Corners[]

The route again split as it entered Gardner. These three alignments reunited at Welco Corners, which is located in present-day Bolingbrook.

1926 route through Joliet[]

The original eastern path of US 66, most of which is currently designated as IL 53, served Gardner, Braceville, Godley, and Braidwood before entering Wilmington. The section of Route 66 from Wilmington to Joliet was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 5, 2006,[6] and travels through mostly agricultural land, although the area also includes the former Joliet Arsenal. This segment of Route 66 runs 15.9 miles (25.6 km) through Joliet, Jackson, Wilmington and Florence Townships in Will County. It begins in Wilmington and ends just short of the I-80 interchange in Joliet.[9]

Several structures along this section are included in a National Register listing. Contributing structures to the listing include one bridge, one overpass and four concrete box culverts. The three-span, continuous steel multibeam bridge, in the northbound lanes, dates to 1950 and features concrete balusters and top rails. The box culverts were built as part of the 1926 road's foundation and range in width from five to nine feet (1.5 to 2.7 m). There are also four non-historic bridges constructed during the 1970s and 1980s along this stretch of US 66.[9]

Currently, IL 53 coincides with Route 66 through Joliet. North of Joliet, the early roadbed was four lanes wide by 1936.[10] It passed by the notorious Stateville Penitentiary, then in unincorporated Joliet but now in Crest Hill ever since that suburb was created. After IL 53 splits to the north in Romeoville, the road is signed only as Historic US 66. The later alignments rejoin this original path at Welco Corners, an early crossroads now part of Bolingbrook that by the 1920s had added a truck stop and other motorists' services.

When this path was bypassed by the redirected US 66 in 1940, it became Alternate US 66, following Chicago Street through the central city on the east bank of the Des Plaines River and Broadway on the west bank. Decades later, even this business route split through the central city into northbound lanes on Scott Street and southbound lanes on Ottawa Street, with the split rejoining on Chicago at Columbia Street before crossing the Ruby Street Bridge to the west bank and onto Broadway, going north toward Crest Hill. All three of these north–south downtown streets offer a number of important historical structures for travelers to visit.

From south to north, these include the Beaux Arts style Joliet Union Station by Jarvis Hunt; the historic Church of St. Anthony, the oldest public building still in use in Joliet; the endangered St. Mary Carmelite Church by Patrick Keely; the Joliet Public Library, designed by Daniel Burnham; the restored Rialto Square Theatre, one of the few surviving movie palaces of the more than 400 designed by Rapp & Rapp; the Georgian Revival Louis Joliet Hotel, transformed into apartments but still an unfinished renovation project; the Neoclassical Old Joliet Post Office; the Auditorium Building block by G. Julian Barnes, a classic Joliet limestone building; the Joliet Area Historical Museum, which occupies another Julian Barnes building, the former Ottawa Street Methodist Church; the Italianate style Joliet Chamber of Commerce Clubhouse, now the JJC Renaissance Center, and the old Joliet YMCA across the street, both designed by Burnham Brothers; two Art Deco structures, the Public Service Building on Ottawa and the KSKJ Building on Chicago Street further north; and the magnificent Bedford limestone St. Joseph Church, designed by Burnham protege William J. Brinkmann and the largest church in the city, whose twin spires could be seen for miles around when Route 66 was new.

There are also at least two pop-culture points of interest. One is just north of downtown Joliet, not far from the city center campus of Joliet Junior College. Sherb Noble opened the first Dairy Queen on June 22, 1940, at 501 N. Chicago Street in Joliet. Although the shop closed and the last soft serve ice cream was sold in the early 1950s, the building was designated a local landmark in November 2010.[11] Across the river at the south end of Route 66 Park is the Rich & Creamy ice cream stand on Broadway, easily recognized by the statues of Elwood and Jake Blues, the Blues Brothers, posed on the roof. This classic stand is open for business from mid-spring through late fall, depending on the weather, and is a welcome stop on the tour.

1940 route through Plainfield[]

The new western route was opened in 1940 and began in Gardner on the other (west) side of the Southern Pacific railroad tracks, taking over portions of IL 59 and IL 126.[12][13] Its main purpose was to bypass Joliet. This route also served Braceville, Godley, and Braidwood but then curved north to Channahon, Shorewood, and Plainfield, rejoining the original route at Welco Corners. In Plainfield, this new route overlapped US 30 (Lincoln Highway) for a short distance. After this road was opened, the original route through Joliet was redesignated as Alternate US 66. Between Gardner and Braceville, a magnificent through-arch bridge carried this alignment of Route 66 over railroad tracks; unfortunately it deteriorated beyond repair and was demolished in 2000. Beyond Braidwood, motorists can follow this 1940 alignment on IL 129, I-55, IL 59, IL 126, and I-55 again.

1957 freeway route[]

In 1957, a new freeway, which is today's I-55, was opened as US 66 between Gardner and Welco Corners, bypassing both Braidwood and Plainfield. Most portions of the 1940 western alignment that were not incorporated into the new freeway reverted to their previous state routes, except for the section from Gardner through Braidwood, which became IL 129.[14] This freeway was originally designated only as US 66 and was then also designated as I-55 in 1960,[15] becoming the first complete section of I-55 in Illinois. It served as mainline US 66 for 19 years, from 1957 to 1976, longer than either of the two previous alignments.

Between 2007 and 2008, the section of I-55 between I-80 and Welco Corners, originally built as the redirected path of US 66 in 1957, was rebuilt and widened to three lanes in each direction to accommodate modern traffic loads.[16] However, between I-80 and Gardner, I-55 today remains mostly as it was as US 66 in 1957. This heritage is evident, with fully mature trees in interchange medians, several 1957-era motels and gas stations still in operation, and several original bridges still in use, such as the Smith Bridge[17] over the Des Plaines River and the nearby Blodgett Road overpass.

Welco Corners to Chicago[]

From Welco Corners in Bolingbrook to Indian Head Park, I-55 was built on top of much of old US 66. Here, Route 66 passed through what is now Woodridge, Darien, Willowbrook and Burr Ridge—none of which were in existence in 1926 when the route was created and did not come into existence as suburbs until the late 1950s through late 1960s. The stretch from Darien northeast through what is now Countryside and Hodgkins was then part of a large rural farmland collectively known as Lyonsville, as the eastern end of it was located in Lyons Township in Cook County. This section of mainline I-55 is today signed as Historic US 66, though inconsistently so, making it difficult for travelers to follow along the original 1926 path; however, a section of the original highway that now serves as the two-way north frontage road in Darien, Willowbrook and Burr Ridge retains the old Route 66 feel. The original path is slightly difficult to follow here, due to swings north around the I-55 interchanges between Lemont Road and County Line Road, but not impossible, and taking the north frontage road leads travelers past several sites of historic interest, including Cass Cemetery and the former Martin B. Madden mansion known as Castle Eden (now a Carmelite priory) in Darien as well as the International Harvester experimental fields in Burr Ridge (once known as Harvester, Illinois after the plant located there).

Near the Cass Avenue instersection, Route 66 and I-55 pass by the northern edge of the Argonne National Laboratory campus. A mile or so further east near the IL 83 interchange, Dell Rhea's Chicken Basket in Willowbrook is still a popular stop for motorists on the route, although being cut off from the Interstate did cost it a significant amount of business after I-55 was built and during the 1960s through 1980s. At the Indian Head Park interchange with I-294 (Tri-State Tollway), I-55 separates from US 66 to follow a more southerly route as the Stevenson Expressway while Historic US 66 continues eastward on Joliet Road, passing by the historic Lyonsville Congregational Church at Wolf Road and traversing Countryside, Hodgkins and McCook.

The original path of Route 66 on Joliet Road intersects the overlapping US 12/US 20/US 45 at LaGrange Road in Countryside before touching the edge of Hodgkins near East Avenue. A brief stretch of Route 66 in McCook between East Avenue and 55th Street west of First Avenue has been permanently damaged by a local quarry and is closed, and Historic US 66 detours onto East Avenue north to 55th Street east before intersecting again with Joliet Road. The detour around the quarry is well marked. In McCook, the route passes by the former Snuffy's 24-Hour Grill, now restored and transformed into the Steak N Egger on Route 66.

The route continues northeast on Joliet Road through McCook and Lyons, then jogs north briefly onto Harlem Avenue to Ogden Avenue in Berwyn, where it meets US 34. From Berwyn, Route 66 continues northeast on Ogden Avenue past the Berwyn Route 66 Museum, passing through Cicero before entering Chicago on a diagonal and progressing through the Greater Lawndale area, where it divides North Lawndale from South Lawndale before moving through Douglass Park, the Tri-Taylor Historic District and the Illinois Medical District on the Near West Side.

Turning due east from Ogden Avenue once north of the I-290 (Eisenhower Expressway), Route 66 moves through the Jackson Boulevard Historic District toward the Chicago Loop via Jackson Boulevard. After a construction project during the early- to mid-1950s temporarily designated Jackson Boulevard as one-way east, Jackson Boulevard became one way eastbound permanently in 1955; thus, Route 66 from the West Loop through the downtown area was split, with the westbound lanes relocated to Adams Street.[18]

The eastern endpoint of US 66 was always at US 41. The original 1926 terminus was at Jackson Boulevard and Michigan Avenue, as Michigan Avenue was designated US 41 in 1926.[10] However, when US 41 through most of Chicago was relocated to Lake Shore Drive in 1938, Route 66 was extended an additional two blocks east on Jackson Drive through Grant Park, past Buckingham Fountain, to end at Lake Shore Drive on the shore of Lake Michigan. This last two-block section on Jackson Drive is two way; consequently, when Jackson was designated a one-way street in 1955, westbound Route 66 made a one-block long jog northbound on Michigan Avenue before continuing west on Adams.[18]

The current "End Historic Illinois U.S. Route 66" markers are located on Jackson (eastbound) and the "Start Historic Illinois U.S. Route 66" markers are on Adams (westbound) at Michigan Avenue, in the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District, in recognition of the original eastern terminus of US 66 at Michigan and Jackson. The historic eastern terminus is marked by the southwest corner of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Fountain of the Great Lakes in the Art Institute's South Garden along Michigan Avenue; both the museum and the fountain were already there long before the route's inauguration at that intersection in November 1926 and remain there today.[19]

Major intersections[]

Distances listed are based on entering Illinois via the Veterans Memorial Bridge and following an alignment through Plainfield, using the last known non-freeway route where drivable.

| County | Location | mi[20] | km | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Clair | East St. Louis | 0 | 0.0 | Missouri state line (Veterans Memorial Bridge over the Mississippi River) | |

| west end of US 67 Alt. overlap | |||||

| east end of US 50 overlap | |||||

| | east end of US 67 Alt. overlap; now IL 203 north | ||||

| Fairmont City | west end of IL 111 overlap | ||||

| St. Clair–Madison county line | east end of IL 111 overlap | ||||

| Madison | Collinsville | west end of IL 157 overlap | |||

| | east end of IL 157 overlap | ||||

| Collinsville | west end of IL 159 overlap | ||||

| east end of IL 159 overlap | |||||

| | interchange; east end of US 40 overlap | ||||

| | interchange; now IL 162 | ||||

| | interchange | ||||

| Hamel | interchange | ||||

| | interchange | ||||

| Macoupin | | ||||

| Montgomery | | 51 | 82 | ||

| | |||||

| | |||||

| Sangamon | interchange | ||||

| | |||||

| Springfield | |||||

| 96 | 154 | west end of US 54 overlap | |||

| | east end of US 54 overlap | ||||

| | |||||

| | |||||

| Logan | Lincoln | west end of IL 121 overlap | |||

| east end of IL 121 overlap | |||||

| McLean | | interchange | |||

| | interchange | ||||

| Bloomington | |||||

| | |||||

| | interchange | ||||

| | |||||

| Livingston | | ||||

| | |||||

| | interchange | ||||

| | |||||

| Grundy | | 225 | 362 | now IL 53 north | |

| Will | Braidwood | 229 | 369 | ||

| | interchange | ||||

| Troy | |||||

| Plainfield | west end of US 30 overlap | ||||

| east end of US 30 overlap | |||||

| | 263 | 423 | |||

| Welco Corners | 264 | 425 | |||

| DuPage | Darien | 274 | 441 | interchange | |

| Cook | | 275 | 443 | ||

| McCook | now 1st Avenue | ||||

| Lyons–Stickney line | west end of IL 42A overlap; now IL 43 south | ||||

| Lyons–Berwyn line | 280 | 450 | east end of IL 42A overlap; west end of US 34 overlap; now IL 43 north | ||

| Cicero | interchange | ||||

| Chicago | |||||

| one-block overlap (westbound only) | |||||

| 291 | 468 | ||||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

Structures[]

Filling stations[]

Filling stations were essential to the success of a trans-national road such as Route 66. Stations evolved their own unique design types and filling station architecture varied by period, at one time or another all major design types were represented along US 66 in Illinois. The existence of Route 66, and its alignment which ran parallel to much of the Chicago–St. Louis-running Chicago and Alton Railroad, itself made gasoline distribution simpler.[21] The earliest gas stations were curbside but these were quickly rendered obsolete because of their tendency to back up traffic when a customer used the roadside pumps. The curbside filling station was the first type of business to use the actual term "filling station". Other types of gas stations evolved such as the house or cottage type, the house and canopy, the house and bays, and the oblong box type.[21] Examples of extant filling stations along Route 66 in Illinois can be found in varying states of disrepair, and a few have been fully restored.[21]

Restaurants[]

In the early years of Route 66, many motorists brought their own food along with them and cooked it on the road. Constrained by tight finances and a mistrust of the unknown quality of road food, these earliest travelers were often reluctant to eat out. By the 1930s, this attitude had eased somewhat, and more motorists were eating out along the road. As drivers and automobiles on the road increased, so too did opportunities for fast food. One pioneer in this field was the White Castle chain, founded in 1921; the oldest White Castle restaurant on Route 66 is still in business in Berwyn.[22]

The road food trend was aided by entrepreneurs such as Howard Johnson who provided predictable, simple dishes—comfort food for the weary traveler. Many of the first roadside cafés were part of motor camp complexes, but others, such as Johnson's started explicitly as cafes and evolved further from there.[23] Large companies, such as Johnson's, or the Steak 'n Shake chain which began in Normal and was based on the pioneering idea of curbside service at the car, enjoyed success alongside what were mostly "mom-and pop" eateries dotting the Mother Road.[23][24]

Some locations along Route 66 in Illinois became known for their cuisine. One example is the state capital, Springfield. The city has long had an affiliation with food. The corn dog on a stick was invented in the city under the name "Cozy Dog", although there is some debate to the actual origin of the popular snack.[25][26] The Cozy Dog Drive In has been a Springfield Route 66 staple since 1950.[27] One of the first U.S. drive-thru restaurant windows is still in operation in Springfield on Route 66 at the Maid-Rite Sandwich Shop.[28]

The oldest restaurant still in operation along the entire stretch of US 66, nationwide, is the Ariston Café in Litchfield.[29] The Ariston is an excellent example of the type of mom and pop operation that flourished along Route 66 in Illinois, as is the Palms Grill Café in Atlanta.[23] Two others are the upstate fried-chicken rivals, White Fence Farm in Romeoville and Dell Rhea's Chicken Basket in Willowbrook. The former is a large, rambling, old-style farmhouse, the latter more like a cozy, neon-lit roadhouse where one can hear live blues on weekend nights; the farm offers an antique-filled gallery for visitors, the roadhouse a spate of Route 66 memorabilia, a neon fowl as its emblem, and loads of knick-knacks celebrating chickens. Each has its fans; both offer the traveler the comfort of a relaxed sit-down meal, and both continue to flourish as unique experiences on the route.

Camps, motor courts, and motels[]

Motorists along Route 66 during the 1920s usually carried the essentials with them and often simply set up camp on a rural roadside. Eventually, tourist camps began to spring up along the highway. At first, these campsites and cabins, offered for 25¢ and 50¢ apiece, were unfurnished; the tourist camps offered few amenities. As amentities such as communal toilets began to appear, travelers began to demand them. The camps gave way to motor courts that consisted of a row of cabins, then motor hotels, long buildings with individual rooms side by side and parking in front of them—the name for which was in time shortened to simply "motel".[30]

Bridges[]

Nearly all bridges along old Route 66 in Illinois are constructed from concrete, with very few exceptions. These concrete bridges are simple, lack ornamentation, and all of their major components—abutments, piers, floor beams, decks, stringers, and railings—were constructed from concrete. The only ornamentation is found in the railings, which sometimes contained balusters. Between 1926 and 1940, most of the Route 66 bridges in Illinois were built as two-lane spans. Later incarnations built after 1940 had two lanes in each direction.[31]

One exception to these simple bridges was the now-demolished, magnificent steel bowstring arch bridge at Braceville. There are three notable exceptions that remain. All three are in the greater metropolitan Chicago area: the Jackson Boulevard and Adams Street Bridges over the South Branch of the Chicago River, and the over the Des Plaines River in Joliet. The Jackson, Adams and Ruby Street bridges are the only three remaining movable span bridges on the entire length of Route 66 in eight states, and they are marvels of modern engineering: Chicago-style double-leaf bascule trunnion bridges. The bridge at Adams Street and its neighbor at Jackson Boulevard are the only two single deck bridges in the city that represent the Plan of Chicago's ideal" downtown river bridge.[32] The Jackson and Adams bridges are also among the oldest spans still in use along Route 66 and two of the busiest in Chicago—therefore probably in the state—due to their heavy volume of weekday pedestrian and commuter traffic crossing the bridges to and from nearby Union Station.

Museums and attractions[]

Illinois is home of various museums devoted to the history of US 66, such as the Berwyn Route 66 Museum in Berwyn, the Joliet Area Historical Museum's Route 66 Welcome Center, the Illinois Route 66 Association Hall of Fame and Museum in Pontiac, and the Cruisin' with Lincoln Visitors Center,[33] inside the McLean County Museum of History in Bloomington, Illinois.[34] Vehicles used by late Route 66 travelling artist Bob Waldmire, including a Volkswagen Type 2 minibus that inspired the creation of Pixar animated character Fillmore in the film Cars, are part of the museum collection in Pontiac. Two other museums of interest in Pontiac are the International Walldog Mural and Sign Art Museum[35] and the Pontiac–Oakland Museum.[36] The newest Route 66 museum is the Litchfield Museum and Route 66 Welcome Center, which opened in 2012 across from the Ariston Cafe. This museum houses an extensive history of the city of Litchfield and offers guided tours and special events.[37]

Route 66 in Illinois is also famous for some very quirky jumbo-size attractions, such as the former Bunyon's Paul Bunyan statue, a 19-foot (5.8 m) "Muffler Man" giant originally from a Berwyn hot dog shack that now stands in the quaint downstate community of Atlanta; the similar Gemini Giant in Wilmington; the largest wind farm East of the Mississippi River, Twin Groves Wind Farm, just east of Bloomington, with more than 240 turbines across 22,000 acres (8,900 ha); the Railsplitter Covered Wagon in Lincoln, the world's largest according to Guinness Book of World Records; the Route 66 mural in Pontiac that depicts the world's largest US 66 shield; and the Tall Bunny at Henry's Ra66it Ranch in Staunton.[38]

There are a number of other attractions along Historic US 66 that are in the process of being restored, such as Sprague's Super Service gas station in Normal[39] and The Mill on 66 restaurant in Lincoln.[40] Both sites have received numerous grants and philanthropic donations, but are still in need of project funding to complete their restoration.

The central Illinois section of Route 66 includes some of the territory that Lincoln the lawyer covered on the 8th Judicial Circuit.[41] Here, visitors can see several Abraham Lincoln attractions as part of their Route 66 experience. In Springfield, there is the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum,[42] Lincoln's Tomb,[43] and the Lincoln Home National Historic Site[44] with a brand new exhibit of items from the Steven Spielberg movie Lincoln.[45] In the town of Lincoln, which was named for the 16th president and christened by him in 1853,[46] visitors can see the newly expanded Lincoln Heritage Museum on the campus of Lincoln College.[47] Also, visitors can stop in at the David Davis Mansion in Bloomington to learn the story of how Davis became manager of Lincoln's presidential campaign and later was appointed by him to serve as a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.[48] This section of Route 66 also offers two other interesting side trips: Illinois Amish Country[49] and the Shelbyville State Fish and Wildlife Area.[50]

Significance[]

US 66 has come to stand for the collective, American tourist experience and holds a special place in American popular culture. There is a certain nostalgic appeal to Route 66 that is associated with the thrill of the open road that has contributed to its popularity.[51] Looking at the historic roadway through Illinois from a different perspective, it reveals a unique history that tells the story of movement and road building across the prairie. Study of the highway in Illinois also reveals the evolution of the Interstate Highway System and the growing popularity of automobiles.[51]

Aside from the six sections of the route in Illinois that have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the entire stretch of US 66 through Illinois has been declared a National Scenic Byway and is alternatively known as the Illinois Route 66 Scenic Byway.[6][52] The 436-mile (702 km) stretch of road was declared the Illinois Route 66 Scenic Byway on September 22, 2005 by the U.S. Department of Transportation.[52][53]

See also[]

U.S. Roads portal

U.S. Roads portal Illinois portal

Illinois portalNational Register of Historic Places portal

Notes[]

- ^ That spelling is particular to the area.

References[]

- ^ U.S. Route Numbering Subcommittee (June 25, 1974). "U.S. Route Numbering Subcommittee Agenda" (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 7 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Pre-1930 Segment of Route 66, Chatham to Staunton". Legends of America. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Henson, Darold Leigh. "8. Route 66 Overview Map of Lincoln with 42 Sites, Descriptions, & Photos". Mr. Lincoln, Route 66, and Other Highlights of Lincoln, Illinois.[self-published source]

- ^ a b c d e f Seratt, Dorothy R.L. & Ryburn-Lamont, Terri (August 1997). "Historic and Architectural Resources of Route 66 Through Illinois" (PDF). National Register Information System, National Register of Historic Places (Multiple Property Documentation Form). National Park Service. pp. 3–20. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Newton, David & Seratt, Dorothy R.L. (January 2003). "Route 66, Cayuga to Chenoa" (PDF). HAARGIS Database (National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Newton, David (August 7, 2001) [November 1998]. "Route 66, Litchfield to Mount Olive" (PDF). HAARGIS Database (National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b "Illinois Route 66 Corridor Itinerary" (PDF). Illinois Route 66 Heritage Project. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ a b Thomason, Phillip & Douglass, Teresa (November 9, 2005). "Alternate Route 66, Wilmington to Joliet" (PDF). HAARGIS Database (National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Illinois Secretary of State & Rand McNally (1936). Road Map Illinois (Map). [c. 1:950,000 and c. 1:1,110,000]. Springfield: Illinois Secretary of State. Main map; Chicago and Vicinity inset – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ Owen, Mary (November 21, 2010). "From Queen of Dairies to King of Kings". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ Illinois Secretary of State & Rand McNally (1939). Illinois Road Map (Map) (1939–1940 ed.). c. 1:918,720. Springfield: Illinois Secretary of State – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ Illinois Secretary of State & Rand McNally (1940). Illinois Road Map (Map). c. 1:918,720. Springfield: Illinois Secretary of State – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ Illinois Division of Highways & H.M. Gousha (1957). Illinois Official Highway Map (Map). [1:805,000]. Springfield: Illinois Division of Highways – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ Illinois Division of Highways & H.M. Gousha (1960). Illinois Official Highway Map (Map). [1:790,00]. Springfield: Illinois Division of Highways – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ "Governor Blagojevich Announces Completion of Interstate 55 Widening Project" (Press release). Office of the Governor. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013.

- ^ "Smith Bridge". Bridge Hunter.[self-published source]

- ^ a b Illinois Division of Highways (1955). Illinois Official Highway Map (Map). [1:805,000]. Springfield: Illinois Division of Highways. Chicago and Vicinity inset – via Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ Sanderson, Dale (June 21, 2012). "Historic U.S. Highway Endpoints in Chicago". U.S. Ends.com. Retrieved September 24, 2012.[self-published source]

- ^ Google (August 25, 2012). "Overview Map of US 66 in Illinois" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c Seratt & Ryburn-Lamont (1997), pp. 45–49.

- ^ "Get Your Kicks: Oak Park Area's Route 66 Legacy & Roadside Attractions". Visit Oak Park. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Seratt & Ryburn-Lamont (1997), pp. 53–55.

- ^ Clark, Marian (2000). The Route 66 Cookbook: Comfort Food from the Mother Road. Council Oak Books. p. 14. ISBN 1571781285. Retrieved October 1, 2007 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Interview with Edwin Waldmire" (PDF). Oral History Collections. Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Brookens Library, University of Illinois-Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Storch, Charles (August 16, 2006). "Birthplace (maybe) of the corn dog". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 1, 2007 – via EBSCO.

- ^ Kaszynski, William (2003). Route 66: Images of America's Main Street. McFarland & Company. p. 20. ISBN 0786415533. Retrieved October 1, 2007 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pearson, Rick (February 9, 2007). "A Guide for the National Press". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ Hoekstra, David (July 13, 2006). "Dining With the Locals on Illinois 66". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 1, 2007 – via Route 66 University.

- ^ Seratt & Ryburn-Lamont (1997), pp. 49–52.

- ^ Seratt & Ryburn-Lamont (1997), pp. 57–59.

- ^ "W. Adams St. Bridge - 85th Anniversary" (PDF). ChicagoLoopBridges.com. August 26, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ "Cruisin' with Lincoln on 66". Route 66 Visitors Center in Illinois. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "History of the McLean County Museum of History". Mclean County Museum of History. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "About the Museum". International Walldog Mural & Sign Art Museum. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "About Us". Pontiac–Oakland Museum and Resource Center. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Visit". Litchfield Museum & Route 66 Welcome Center. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Land of Lincoln Jumbo Trail". Land of Lincoln Regional Tourism Development Office. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Sprague's Super Service". Normal, Illinois: National Park Service. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Mill on Route 66 in Lincoln, Illinois". Route 66 Heritage Foundation of Logan County. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln's 8th Judicial Circuit". Looking for Lincoln Heritage Coalition. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum". Illinois Department of Central Management Services. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln Tomb". Lincoln Tomb and War Memorials State Historic Site. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln Home". National Park Service. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln: History to Hollywood". Illinois Department of Central Management Services. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Attraction Information for Logan County, Illinois". ExploreLoganCounty.com. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Lincoln Heritage Museum". Lincoln Heritage Museum. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to the David Davis Mansion State Historic Site". David Davis Mansion State Historic Site. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Attractions: Amish Country". Land of Lincoln Regional Tourism. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Attractions:Lake Shelbyville". Land of Lincoln Regional Tourism. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Seratt & Ryburn-Lamont (1997), pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b "Historic Route 66: Illinois". America's Byways. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^ Ambrose, David (September 29, 2005). "Illinois Historic Route 66 Earns National Scenic Byway Designation". South County News. Gillespie, IL. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

External links[]

Route map:

| ( • help)

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to U.S. Route 66 in Illinois. |

- U.S. Route 66 in Illinois

- Roads on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

- U.S. Highways in Illinois

- National Scenic Byways

- National Register of Historic Places in Cook County, Illinois