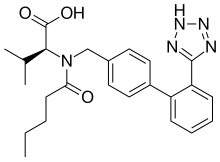

Valsartan

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Diovan, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697015 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Angiotensin II receptor antagonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25% |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Elimination half-life | 6 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney 30%, biliary 70% |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.113.097 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H29N5O3 |

| Molar mass | 435.528 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Valsartan, sold under the trade name Diovan among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, and diabetic kidney disease.[3] It is a reasonable initial treatment for high blood pressure.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3] Versions are available as the combination valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, valsartan/amlodipine, valsartan/amlodipine/hydrochlorothiazide, or valsartan/sacubitril.[3][4]

Common side effects include feeling tired, dizziness, high blood potassium, diarrhea, and joint pain.[3] Other serious side effects may include kidney problems, low blood pressure, and angioedema.[3] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby and use when breastfeeding is not recommended.[5] It is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist and works by blocking the effects of angiotensin II.[3]

Valsartan was patented in 1990, and came into medical use in 1996.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[7] In 2018, it was the 96th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 7 million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical uses[]

Valsartan is used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, and to reduce death for people with left ventricular dysfunction after having a heart attack.[10][11]

High blood pressure[]

It is a reasonable initial treatment for high blood pressure as are ACE inhibitors, calcium-channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.[3]

Heart failure[]

There is contradictory evidence with regard to treating people with heart failure with a combination of an angiotensin receptor blocker like valsartan and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, with two major clinical trials showing a reduction in death, and two others showing no benefits, and more adverse effects including heart attacks, hypotension, and renal dysfunction.[10]

Diabetic kidney disease[]

In people with type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure or albumin in the urine, valsartan is used to slow the worsening and the development of end-stage kidney disease.[12]

Contraindications[]

The packaging for valsartan includes a warning stating the drug should not be used with the renin inhibitor aliskiren in people with diabetes mellitus. It also states the drug should not be used in people with kidney disease.[11]

Valsartan falls in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category D and includes a black box warning for fetal toxicity.[11][5] Discontinuation of these agents is recommended immediately after detection of pregnancy and an alternative medication should be started.[11] The U.S. labeling makes no recommendation regarding continuation or discontinuation of valsartan for breast-feeding mothers.[11] The Canadian labeling does not recommend use by nursing women.[13]

Side effects[]

Rates of side effects depends on the reason the medication is used.

Heart failure[]

Rates of adverse effects are based on a comparison versus placebo in people with heart failure.[11] Most common side effects include dizziness (17% vs 9% ), low blood pressure (7% vs 2%), and diarrhea (5% vs 4%).[11] Less common side effects include joint pain, fatigue, and back pain (all 3% vs 2%).[11]

Hypertension[]

Clinical trials for valsartan treatment for hypertension versus placebo demonstrate side effects like viral infection (3% vs 2%), fatigue (2% vs 1%) and abdominal pain (2% vs 1%). Minor side effects that occurred at >1% but were similar to rates from the placebo group include:[11]

- headache

- dizziness

- upper respiratory infection

- cough

- diarrhea

- rhinitis/sinusitis

- nausea

- pharyngitis

- edema

- arthralgia

Kidney failure[]

People treated with ARBs including valsartan or diuretics are susceptible to conditions of developing low renal blood flow such as abnormal narrowing of blood vessel in kidney, hypertension, renal artery stenosis, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, severe congestive heart failure, or volume depletion whose renal function is in part dependent on the activity of the renin-angiotensin system like efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction done by angiotensin II are at high risk of deterioration of renal function comprising acute kidney failure, oliguria, worsening azotemia or heightened serum creatinine.[11] When blood flow to the kidneys is reduced, the kidney activates a series of response that triggers angiotensin release to constrict blood vessels and facilitate blood flow in the kidney.[14] So long as the nephron function degradation is being progressive or reaches clinically significant level, withhold or discontinue valsartan is warranted.[11][15][16][17]

Interactions[]

The U.S. prescribing information lists the following drug interactions for valsartan:

- Other inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system may increase the risks of low blood pressure, kidney problems, and hyperkalemia.

- Potassium sparing diuretics, potassium supplements, salt substitutes containing potassium may increase the risk of hyperkalemia.

- NSAIDs may increase the risk of kidney problems and may interfere with blood pressure-lowering effects.

- Valsartan may increase the concentration of lithium.[11]

- Valsartan and other angiotensin-related blood pressure medications may interact with the antibiotics co-trimoxazole or ciprofloxacin to increase risk of sudden death due to cardiac arrest.[18]

Food interaction[]

With the tablet, food decreases the valsartan tablet taker's exposure to valsartan by about 40% and peak plasma concentration (Cmax) by about 50%, evidenced by AUC change.[11]

Pharmacology[]

Mechanism of action[]

Valsartan blocks the actions of angiotensin II, which include constricting blood vessels and activating aldosterone, to reduce blood pressure.[19] The drug binds to angiotensin type I receptors (AT1), working as an antagonist. This mechanism of action is different than that of the ACE inhibitor drugs, which block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. As valsartan acts at the receptor, it can provide more complete angiotensin II antagonism since angiotensin II is generated by other enzymes as well as ACE. Also, valsartan does not affect the metabolism of bradykinin like ACE inhibitors do.[19]

Pharmacodynamics[]

Pharmacokinetics[]

AUC and Cmax values of valsartan are observed to be approximately linearly dose-dependent over therapeutic dosing range. Owing to its relatively short elimination half life attribution, valsartan concentration in plasma doesn't accumulate in response to repeated dosing.[11]

Society and culture[]

Economics[]

In 2010, valsartan (trade name Diovan) achieved annual sales of $2.052 billion in the United States and $6.053 billion worldwide.[20] The patents for valsartan and valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide expired in September 2012.[21][22]

Combinations[]

Valsartan is combined with amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) (or both) into single-pill formulations for treating hypertension with multiple drugs.[3][23][24][25] Valsartan is also available as the combination valsartan/sacubitril.[4][26][27] It is used to treat heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.[27][28]

Recalls[]

On 6 July 2018, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recalled certain batches of valsartan and valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide film-coated tablets distributed in 22 countries in Europe, plus Canada.[29] Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical Co. (ZHP) in Linhai, China manufactured the bulk ingredient contaminated by N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a carcinogen.[30] The active pharmaceutical ingredient was subsequently imported by a number of generic drugmakers, including Novartis, and marketed in Europe and Asia under their subsidiary Sandoz labeling, and in the UK by Dexcel Pharma Ltd and Accord Healthcare.[29]

In Canada, the recall involves five companies and a class action suit has been initiated by a private law firm.[31][32] Authorities believe the degree of contamination is negligible, and advise those taking the drug to consult a doctor and not to cease taking the medication abruptly. On 12 July 2018, The National Agency of Drug and Food Control (NA-DFC or Badan POM Indonesia) announced voluntary recalls for two products containing valsartan produced by Actavis Indonesia and Dipa Pharmalab Intersains.[33] On 13 July 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced voluntary recalls of certain supplies of valsartan and valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide in the U.S. distributed by Solco Healthcare LLC, Major Pharmaceuticals, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.[34][30] Hong Kong's Department of Health initiated a similar recall.[35] On 2 August 2018, the FDA published two lengthy, updated lists, classifying hundreds of specific U.S. products containing valsartan into those included versus excluded from the recall.[36][37] A week later, the FDA cited two more drugmakers, Zhejiang Tianyu Pharmaceuticals of China and Hetero Labs Limited of India, as additional sources of the contaminated valsartan ingredient.[38][37]

In September 2018, the FDA announced that retesting of all valsartan supplies had found a second carcinogenic impurity, N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), in the recalled products made by ZHP in China and marketed in the U.S. under the Torrent Pharmaceuticals (India) brand.[39]

According to a 2018 Reuters analysis of national medicines agencies' records, more than 50 companies around the world have recalled valsartan mono-preparations or combination products manufactured from the tainted valsartan ingredient. The contamination has likely been present since 2012 when the manufacturing process was changed and approved by EDQM and FDA authorities. Based on inspections in late 2018, both agencies have suspended the Chinese and Indian manufacturers' certificates of suitability for the supply of valsartan in the EU and the U.S.[40]

In 2019, many more preparations of valsartan and its combinations were recalled due to the presence of the contaminant NDMA.[41][42][43]

In August 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provided guidance to marketing authorization holders on how to avoid the presence of nitrosamine impurities in human medicines and asked them to review all chemical and biological human medicines for the possible presence of nitrosamines and to test the products at risk.[44]

Shortages[]

Since July 2018, numerous recalls of losartan, valsartan and irbesartan drug products have caused marked shortages of these life saving medications in North America and Europe, particularly for valsartan. In March 2019, the FDA approved an additional generic version of Diovan™ to address the issue.[45] According to the agency, the shortage of valsartan was resolved in 03/04/2020,[46] but the availability of the generic form remained unstable into July 2020. Pharmacies in Europe were notified that the supply of the drug, particularly for higher dosage forms, would remain unstable well into December 2020.[47]

Research[]

In people with impaired glucose tolerance, valsartan may decrease the incidence of developing diabetes mellitus type 2. However, the absolute risk reduction is small (less than 1 percent per year) and diet, exercise or other drugs, may be more protective. In the same study, no reduction in the rate of cardiovascular events (including death) was shown.[48]

In one study of people without diabetes, valsartan reduced the risk of developing diabetes mellitus over amlodipine, mainly for those with hypertension.[49]

A prospective study demonstrated a reduction in the incidence and progression of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.[50]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Valsartan Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Valsartan 160 mg capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 19 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Valsartan Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sacubitril and Valsartan Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Valsartan Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 470. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 179. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Valsartan - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Randa H (2011). "Chapter 26. Renin and Angiotensin". In Brunton LL, Chabner B, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Diovan- valsartan tablet". DailyMed. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. (January 2015). "Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 38 (1): 140–9. doi:10.2337/dc14-2441. PMID 25538310.

- ^ "Diovan Product Monograph". Health Canada Drug Product Database. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Kumar A, Fausto A (2010). "11". Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ^ Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. (November 2011). "AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation". Circulation. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 124 (22): 2458–73. doi:10.1161/cir.0b013e318235eb4d. PMID 22052934.

- ^ "KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease" (PDF). 3 (1). KDIGO. January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Zar T, Graeber C, Perazella MA (7 June 2007). "Recognition, treatment, and prevention of propylene glycol toxicity". Seminars in Dialysis. Wiley. 20 (3): 217–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-139x.2007.00280.x. PMID 17555487. S2CID 41089058.

- ^ Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, Antoniou T, Hollands S, Mamdani MM, et al. (October 2014). "Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study". BMJ. 349: g6196. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6196. PMC 4214638. PMID 25359996.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Katzung BG, Trevor AJ (2015). "Chapter 11". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (13 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0071825054.

- ^ "Novartis Annual Report 2010" (PDF).

- ^ Philip Moeller (29 April 2011). "Blockbuster Drugs That Will Go Generic Soon". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ Eva Von Schaper (5 August 2011). "Novartis's Jimenez Has Blockbuster Plans For Diovan After Patent Expires". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Exforge- amlodipine besylate and valsartan tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Diovan HCT- valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Exforge HCT- amlodipine valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Entresto- sacubitril and valsartan tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 1 September 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fala L (September 2015). "Entresto (Sacubitril/Valsartan): First-in-Class Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor FDA Approved for Patients with Heart Failure". Ah & Db. 8 (6): 330–334. PMC 4636283. PMID 26557227.

- ^ Khalil P, Kabbach G, Said S, Mukherjee D (2018). "Entresto, a New Panacea for Heart Failure?". Cardiovascular & Hematological Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (1): 5–11. doi:10.2174/1871525716666180313121954. PMID 29532764.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christensen J. "Common heart drug recalled in 22 countries for possible cancer link". CNN. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edney A, Berfield S, Yu E (12 September 2019). "Carcinogens Have Infiltrated the Generic Drug Supply in the U.S." Bloomberg News. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Several drugs containing valsartan being recalled due to contamination with a potential carcinogen". Health Canada. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "Valsartan Class Action". valsartanclassaction.com. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "Penjelasan BPOM RI Tentang Penarikan Obat Antihipertensi Yang Mengandung Zat Aktif Valsartan". National Agency of Drug and Food Control of Republic of Indonesia (Badan POM) (in Indonesian). Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ Christensen J. "FDA joins 22 countries' recall of common heart drug". CNN. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "Hong Kong health department issues recall for five heart drugs containing valsartan that was made in China". South China Morning Post. 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "FDA updates on valsartan recalls". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker (ARB) Recalls (Valsartan, Losartan, and Irbesartan)". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 August 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Patrice Wendling (13 August 2018). "More Drug Makers Tagged as Valsartan Recall Grows". WebMD. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "FDA provides update on its ongoing investigation into valsartan products; and reports on the finding of an additional impurity identified in one firm's already recalled products". Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 13 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Harney A, Hirschler B (22 August 2018). "Toxin at heart of drug recall shows holes in medical safety net". Reuters. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Abdin, Ahmad Yaman; Yeboah, Prince; Jacob, Claus (January 2020). "Chemical Impurities: An Epistemological Riddle with Serious Side Effects". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (3): 1030. doi:10.3390/ijerph17031030. PMC 7038150. PMID 32041209.

- ^ Radcliffe S (19 June 2019). "Blood Pressure Medications Recall". Healthline. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "ARB Recalls: Valsartan, Losartan and Irbesartan". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Nitrosamine impurities". European Medicines Agency. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2020. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Clanton, N. (March 13, 2019). FDA approves generic blood pressure drug to alleviate shortages caused by numerous recalls The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Current and Resolved Drug Shortages and Discontinuations Reported to FDA accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Lieferengpass Valsartan-CT 160mg . Gelbe Liste (in German). Pharmindex. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Haffner SM, Bethel MA, Holzhauer B, Hua TA, et al. (April 2010). "Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (16): 1477–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001121. hdl:2381/21817. PMID 20228403.

- ^ Kjeldsen SE, McInnes GT, Mancia G, Hua TA, Julius S, Weber MA, et al. (2008). "Progressive effects of valsartan compared with amlodipine in prevention of diabetes according to categories of diabetogenic risk in hypertensive patients: the VALUE trial". Blood Pressure. 17 (3): 170–7. doi:10.1080/08037050802169644. PMID 18608200. S2CID 3426921.

- ^ Li NC, Lee A, Whitmer RA, Kivipelto M, Lawler E, Kazis LE, et al. (January 2010). "Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis". BMJ. 340: b5465. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5465. PMC 2806632. PMID 20068258.

External links[]

- "Valsartan". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Amlodipine mixture with valsartan". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Amlodipine besylate mixture with hydrochlorothiazide and valsartan". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Hydrochlorothiazide mixture with valsartan". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Sacubitril mixture with valsartan". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Angiotensin II receptor antagonists

- Biphenyls

- Carboxamides

- Carboxylic acids

- Novartis brands

- Tetrazoles