Wawel Dragon

| Smok Wawelski | |

|---|---|

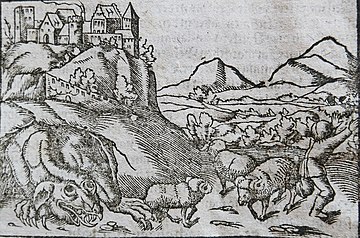

The Wawel Dragon, in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographie Universalis (1544) |

The Wawel Dragon (Polish: Smok Wawelski), also known as the Dragon of Wawel Hill, is a famous dragon in Polish folklore. His lair was in a cave at the foot of Wawel Hill on the bank of the Vistula River. Wawel Hill is in Kraków, which was then the capital of Poland. It was defeated during the rule of Krakus, by his sons according to the earliest account; in a later work, the dragon-slaying is credited to a cobbler named Skuba, or Szewczyk Dratewka.

History[]

The oldest known telling of the story comes from the 13th-century work attributed to Bishop of Kraków and historian of Poland, Wincenty Kadłubek.[1][2]

The inspiration for the name of Skuba was probably a church of St. Jacob (pol. Kuba), which was situated near the Wawel Castle. In one of the hagiographic stories about St. Jacob, he defeats a fire-breathing dragon.[citation needed]

Polish Chronicle (13 c.)[]

According to Wincenty Kadłubek's Polish Chronicle, the Wawel dragon appeared during the reign of King Krakus (lat. Gracchus). The dragon required weekly offerings of cattle, or else humans would have been devoured instead. In the hope of killing the dragon, Krakus called on his two sons, Lech and Krakus II. They could not, however, defeat the creature by hand, so they came up with a trick. They fed him a calf skin stuffed with smoldering sulfur, causing his fiery death. Hungry for power, Krakus then killed his younger brother, Lech, and told others that the dragon killed him. When Krakus became king however, his secret was soon revealed, and he got expelled from the country.[3]

Late Middle Ages[]

Jan Długosz in his 15th-century chronicle wrote that the one who defeated the dragon was King Krakus, who ordered his men to stuff the flesh of a calf skin with flammable substances (sulfur, tinder, wax, pitch, and tar) and set them on fire.[1] The dragon ate the burning meal and died breathing fire just before death.

Another version by Marcin Bielski from the 16th century gave credit to the shoemaker Skuba for defeating the dragon.[4] The story still takes place in Kraków during the reign of King Krakus, the city's legendary founder, and a calf's skin filled with sulfur was used as bait to the dragon. The dragon was unable to swallow this, and drank water until it died. Afterwards, Skuba was rewarded handsomely. Bielski adds, "One can still see his cave under the castle. It is called the Dragon's Cave (Smocza Jama)"[5]

Popular retellings[]

Some of this section's listed sources may not be reliable. (January 2018) |

The most popular, fairytale version of the Wawel Dragon tale takes place in Kraków during the reign of King Krakus, the city's legendary founder. Each day the evil dragon would beat a path of destruction across the countryside, killing the civilians, pillaging their homes, and devouring their livestock. In many versions of the story, the dragon especially enjoyed eating young maidens. Great warriors from near and far fought for the prize and failed.[6] A cobbler's apprentice (named Skuba[7]) accepted the challenge. He stuffed a lamb[7][6] with sulphur and set it outside the dragon's cave. The dragon ate it and became so thirsty, it turned to the Vistula River[6] and drank until it burst. The cobbler married the King's daughter as promised, and founded the city of Kraków.[7][6]

Attempts to explain the legend[]

Legends of the Wawel dragon have similarities with the biblical story about Daniel and the Babylonian dragon.[8] Similar stories are told about Alexander the Great but it is believed that the Kraków story has its own pre-Christian origins.

In addition to attempts to explain the legend of the Wawel Dragon simply as a symbol of evil,[8] there might be some echoes of historical events. According to some historians, the dragon is a symbol of the presence of the Avars on Wawel Hill in the second half of the sixth century, and the victims devoured by the beast symbolise the tribute pulled by them.[9] There are also attempts to interpret the story as a reference to human sacrifices and part of an older, unknown myth.[10]

Wawel Cathedral and Kraków's Wawel Castle stand on Wawel Hill. In front of the entrance to the cathedral, there are bones of Pleistocene creatures hanging on a chain, which were found and carried to the cathedral in medieval times as the remains of a dragon. It is believed that the world will come to its end when the bones will fall on the ground.

The Wawel Cathedral features a statue of the Wawel dragon and a plaque commemorating his defeat by Krakus, a Polish prince who, according to the plaque, founded the city and built his palace over the slain dragon's lair. The dragon's cave below the castle is now a popular tourist stop.

Modern times[]

- A metal sculpture of the Wawel Dragon, designed in 1969 by Bronisław Chromy, was placed in front of the dragon's den in 1972.[11] The dragon has seven heads, but frequently people think that it has one head and six forelegs. To the amusement of onlookers, it noisily breathes fire every few minutes, thanks to a natural gas nozzle installed in the sculpture's mouth.

- The street leading along the banks of the river leading towards the castle is ulica Smocza, which translates as "Dragon Street".

Dragon in culture[]

- Wawel Dragons (Gold, Silver, Bronze Grand Prix Dragons and Dragon of Dragons Special Prize) are awards, usually presented at Kraków Film Festival in Poland

- The Dragon (as "The Beast of Kraków") appeared in the eighth issue of a comic book series Nextwave from Marvel Comics (written by Warren Ellis and drawn by Stuart Immonen).

- The Dragon appears in a series of shorts produced and published by Polish company Allegro. The shorts re-visit classic Polish legends and folk tales in modernised form: in the first short, titled Smok, the dragon is presented as a flying machine used by a mysterious outlaw to capture Kraków girls.

- Wawel Dragon is also one of main characters in Stanisław Pagaczewski's series of books about a scientist Baltazar Gąbka, as well as short animations based on them.

- An archosaur discovered in Lisowice in 2011 was named Smok wawelski after the dragon.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sikorski, Czesław (1997), "Wood Pitch as Combat Chemical in the Light of the Jan Długosz's Annals and Some of the Old Polish Military Treatises", Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Wood Tar and Pitch: 235

- ^ Wincenty Kadłubek, "Kronika Polska", Ossolineum, Wrocław, 2008, ISBN 83-04-04613-X

- ^ https://pbc.gda.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=43988&from=FBC

- ^ Kitowska-Łysiak, Małgorzata; Wolicka, Elżbieta (1999), Miejsce rzeczywiste, miejsce wyobrażone: studia nad kategorią miejsca w przestrzeni kultury, Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego [Scientific Society of the Catholic University of Lublin], p. 231, ISBN 9788387703745,

Gdy w w. XVI projektodawcą sposobu uśmiercenia potwora kreowano krakowskiego szewca Skubę (Bielski) [When, in the 16th century, the architect of the means for killing the monster became the Krakow shoemaker Skuba (Bielski), the implausible tale was made to seem true.]

- ^ Rożek, Michał (1988). Cracow: A Treasury of Polish Culture and Art. Interpress Publ. p. 27. ISBN 9788322322451. (translation of the paragraph from Bielski)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gall, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (2009). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: Europe. Gale. p. 385. ISBN 9781414464305.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McCullough, Joseph A. (2013). Dragonslayers: From Beowulf to St. George. Osprey Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781472801029.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jerzy Strzelczyk: Mity, podania i wierzenia dawnych Słowian. Poznań: Rebis, 2007. ISBN 978-83-7301-973-7.

- ^ Jerzy Strzelczyk: Od Prasłowian do Polaków. Kraków: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1987, s. 75-76. ISBN 83-03-02015-3.

- ^ Maciej Miezian. Smok wawelski. Historia prawdziwa i wbrew pozorom całkiem poważna. „Nasza Historia. Dziennik Polski”. 12, s. 10-13, listopad 2014. ISSN 2391-5633

- ^ Marcin Bielowicz (2011-01-03). "Smok Wawelski :. infoArchitekta.pl" (in Polish). . infoArchitekta.pl . Retrieved 2018-05-14.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wawel Dragon. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Smok Wawelski. |

- European dragons

- Wawel

- Polish legends

- Culture in Kraków

- Polish folklore