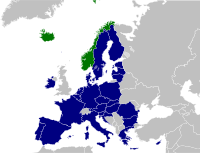

Work–life balance in the European Union

Work–life balance in the European Union is the relation between personal life and paid work in the European Union.[1] The term Work–life balance was

| This article is part of a series on |

Politics of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

commonly introduced in the European Union in the 1990s. Although it is a politicized term both at the academic and the non-academic level, the subject is still considered controversial.[2]

The increasing need of balancing personal and working life is related to the structural changes in society. While the traditional family composition in the first half of the 20th century was characterized by the role of the man as breadwinner and the women as housekeeper,[3] the social changes of the second half of the 20th century required ad hoc policies. Following the improvement of women's education and their involvement in the labour market there has been the necessity of finding a new form of work–life balance.[4]

The matter of balancing work and personal life has a growing importance also due to the inconvenience stemming from an imbalanced work–life which, among others, is the cause of depression, alcohol abuse, low life quality and decreasing personal satisfaction.[5]

Indicators[]

The growing importance of work-life balance brought institutional and non-institutional actor to examine the factors indicating the different levels of work-life balance. Among the indicators found there are;[7]

i) Employment rate of women and men aged 20–49 with children under compulsory school age;

ii) Possibility to work at home;

iii) Commuting time meaning the duration time between the workplace and home;

iv) Care leave entitlement of women and men for care responsibilities for children and / or adults;

v) Entitlement to parental leave and carers leave;

vi) Child care used by employed parents.

Other indicators related to work-life balance are: long working hours, evening work, night work, weekend work and employees' flexible schedules;[8]

A comprehensive list of indices and systems of indicators of job quality can be found at the right of this section.

Overview[]

Since the Treaty of Rome, the free movement of workers is one of the four fundamental economic freedoms of the European Union.[9] The free movement of workers, art 45-48 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, is a highly politicized matter in the EU Internal Market. While through the years the -economic- regional integration in the European Market has removed obstacles to economic growth of EU member States’, the free movement of workers has led also to massive labour mobility. Persons are free to move and search for a job in EU Member States where there is a higher level of work–life balance and a greater welfare system.[10]

Developed countries and in particular EU Member States’ have recognized the relation between a good level of work–life balance and economic growth.

Work–life balance and gender equality in the EU[]

Gender equality and increasing participation of women in the EU Labour Market are key factors for economic growth of the EU and its Member States. In this sense, women's participation in the EU Labour Market improves their economic status producing thus general economic growth.[11]

| Table 1 | |||

| AGE | From 20 to 64 years | ||

| UNIT | Percentage of total population | ||

| TIME | 2020 | ||

| INDIC_EM | Total employment (resident population concept - LFS) | ||

| GEO/SEX | Total | Males | Females |

| European Union - 27 countries (from 2020) | 72,5 | 78,0 | 66,9 |

| Euro area - 19 countries (from 2015) | 71,8 | 76,9 | 66,8 |

| Belgium | 70,0 | 74,1 | 65,9 |

| Bulgaria | 73,4 | 77,8 | 68,9 |

| Czechia | 79,7 | 87,2 | 71,9 |

| Denmark | 77,8 | 81,3 | 74,3 |

| Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) | 80,0 | 83,1 | 76,9 |

| Estonia | 78,8 | 81,8 | 75,8 |

| Ireland | 73,4 | 79,5 | 67,4 |

| Greece | 61,1 | 70,7 | 51,8 |

| Spain | 65,7 | 71,4 | 60,0 |

| France | 72,1 | 75,0 | 69,3 |

| Croatia | 66,9 | 72,5 | 61,3 |

| Italy | 62,6 | 72,6 | 52,7 |

| Cyprus | 74,9 | 81,1 | 69,1 |

| Latvia | 77,0 | 79,0 | 75,2 |

| Lithuania | 76,7 | 77,5 | 75,8 |

| Luxembourg | 72,1 | 75,6 | 68,5 |

| Hungary | 75,0 | 83,1 | 67,0 |

| Malta | 77,4 | 85,7 | 68,0 |

| Netherlands | 80,0 | 84,4 | 75,5 |

| Austria | 75,5 | 79,5 | 71,5 |

| Poland | 73,6 | 81,4 | 65,7 |

| Portugal | 74,7 | 77,8 | 71,9 |

| Romania | 70,8 | 80,3 | 61,0 |

| Slovenia | 75,6 | 78,6 | 72,4 |

| Slovakia | 72,5 | 78,7 | 66,1 |

| Finland | 76,5 | 77,9 | 75,0 |

| Sweden | 80,8 | 83,2 | 78,3 |

| Source dataset: Eurostat 2020[12] | |||

The Lisbon Strategy[]

In March 2000, in Lisbon,[13] EU's heads of state and heads of government reunited in a summit of The European Council, set out an action plan for the sustainable development of EU's economy. In particular, the aim of the action plan, namely the Lisbon Strategy (also known as Lisbon Agenda), was to make by 2010 the EU “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth, with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion”.

By 2010 most targets were non reached by EU Member States and the action plan has been labelled as a failure.

The Lisbon Strategy is knows to be an intergovernmental and non legally binding strategy. Among the reasons of its failure there is the Open Method of Coordination.[14]

The Report from the High Level Group chaired by Wim Kok November 2004 [15] states "At Lisbon and at subsequent Spring European Councils a series of ambitious targets were established to support the development of a world-beating European economy. But halfway to 2010 the overall picture is very mixed and much needs to be done in order to prevent Lisbon from becoming a synonym for missed objectives and failed promises [...] Clearly there are no grounds for complacency. Too many targets will be seriously missed. Europe has lost ground to both the US and Asia and its societies are under strain".

Following the failure of the Lisbon Strategy, a similar strategy, namely the "Europe 2020 Strategy" has been put in place.[16]

Background[]

At the beginning of 2000s, EU's economy presented some weakness in terms of integration of key industries such as energy, pharmaceuticals, telecoms and defense. Investments in Research and Development were about 2.1% of EU's GDP, meaning almost one third less than the US. The EU Member States were losing comparative advantage due to the nature of their industries, considered to be sunset industries, focused on sectors such as steel and textile instead of focusing on new technologies. The idea of the Lisbon Strategy was to better adapt EU's economy to the Wintelism system - global value chain and to modernize the economy.

Content and objective[]

The Lisbon Strategy consisted in three pillars: i) the economic pillar, ii)the social pillar and iii) the environmental pillar.

Under the economic pillar the EU would progressively engage to invest 3% of its GDP in research and Development by 2010. The EU's economy would thus move to a competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy and anticipate major changes caused by the digital sector and in particular by the advent of the internet.

Under the social pillar, EU's social model would be modernized. Investments would focus on education and training and have active policies for employment. In this sense, the EU would move towards a knowledge-based society. The labour market would be more flexible and with a more qualified labour force allowing workers to move towards new technology sectors. In this sense, EU workers would move from sunset industries to sunrise industries (e.g. ICT, biotechnology etc.). Under the social pillar, lifelong learning would be promoted and the labour force would be trained to better adapt to the new technologies. In order to promote this process, the EU attempted to put in place the Danish system of flexicurity.

Under the environmental pillar, integrated in 2001 by the European Council in Gothenburg and composed of non legally binding provisions the EU called for sustainable development.

The Danish model of flexicurity[]

The main idea of the Danish model of flexicurity system[17] is promoting people's training by giving high unemployment benefits. In this regard, high and long lasting unemployment benefits (e.g. lasting more than six months) would allow people to keep the same living standards. In this model, labour mobility is encouraged and workers can move from sunset industry areas to sunrise industry areas. In order to facilitate labour mobility, and in particular labour mobility of women and men with children, the Danish flexicurity system provides a greater number of kindergartens and facilities for parents.

Given the heterogeneity of EU Member States economies and tax systems, the Danish Model of Flexicurity has mostly not been applied by EU Member States.

Work–life balance in EU legislation[]

Parental Leave Directive[]

Source

The Council Directive 2010/18/EU[18] of March 2010 is repealing the Directive 96/34/EC[19] and implements the revised Framework Agreement on parental leave concluded by the European social partners on 18 June 2009. The Directive provides the right of take-off leave for parents following the birth (or the adoption) of their child. This right is given to those having a child of maximum eight years of age. The Directive provides a parental leave of at least four months and in order to equally distribute the parental responsibilities, at least one month will be non-transferable (Directive 2010/18/EU, Annex, Content, Clause 2). However, the Directive does not include provisions on the mandatory payment of parental leave. Clause five of the annex, sets rules concerning employment rights and non-discrimination rights by ensuring that workers returning from parental leave shall return to the same job or when not possible, to a similar position in terms of level and conditions. The Directive applies to all employees, including those having fixed-term contracts, open-ended contracts or part-time contracts. The Directive mentions also the need to find more favorable special leave for adoptive parents and for those having children with disabilities. However, it does not set fixed and binding provisions in this area.

Part-time Work Directive 1997[]

The Directive 97/81/EC[20] (OJ, 1998, L 14) regards the Framework Agreement on part-time working concluded by the Union of Industrial and Employers’ Confederations of Europe (i.e. UNICE), the European Centre of Employers and Enterprises with Public Participation (i.e. CEEP) and the European Trade Union Confederation (i.e. ETUC). This Directive is among the three EU Directives regulating atypical working arrangements (the other two are: i) Directive 1999/70/EC on fixed-term work and ii) Directive 2008/104/EC on temporary agency work). Its main objective is to prevent unjustified discrimination of part-time workers and improve working terms and conditions of those working on a part-time basis.[21]

Work–life balance for parents and carers directive[]

The Directive (EU) 2019/1158[22] of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on work-life balance for parents and carers is repealing Council Directive 2010/18/EU. It was formally adopted on 20 June 2019 and it will be applicable (and thus officially repealing the Council Directive 2010/18/EU) from 2 August 2022.

The directive's objective[]

The main aim of the Directive is to smooth and balance the work of employees who are parents or carers. By doing so, it aims at granting gender equality in treatment and opportunities in the EU labour market. As a consequence, the Directive seeks to boost women's involvement in the EU labour market and realize a more balanced caring liabilities between men and women. Given the low level of take-up leaves of fathers, the Directive sets rules for paid parental and paternity leave with the aim of stimulating equal share of caring responsibilities between men and women. These policies have the ultimate aim of addressing stereotypes related to men's and women's roles in society (EU Directive 2019/1158, recital 11 of the preamble).

In the recital one of the preamble, the objective is introduced with reference to article 153 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter TFEU) which grants equal treatment at work and equal opportunities for men and women in the EU labour market. Furthermore, in the recital two of the preamble, the Directive clearly mentions article 3 of the Treaty of The European Union (hereinafter TEU) and article 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, stressing the importance of promoting gender equality. In the recital five of the preamble, the Directive refers to article 18 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (hereinafter UNCRC) highlighting “the principle that both parents have common responsibilities for the upbringing and development of the child” (UNCRC, article 18). In addition, in the recital nine of the preamble, there is a reference to principles 2 and 9 of the European Pillar of Social Rights respectively promoting equal opportunities and work–life balance for parents and carers.

The directive's content[]

The Directive seeks to achieve gender equality for employees of the EU labour market. To that end, it lays down rights concerning: i) paternity leave, parental leave and carers’ leave; ii) flexible working arrangements for workers who are parents or carers (EU Directive 2019/1158 art. 1).

Before the adoption of the Directive (EU) 2019/1158, in EU law there were no provisions providing fathers’ rights to take paternity leave. The Directive provides for fathers’ (or equivalent second parents) the right to require paternity leave of ten working days on the birth of a child (article 4). This right is granted regardless of the worker's merits or family status and it is on the Member States to establish whether the paternity leave may be taken only after the birth of the child or partially in the period prior the child's birth. The Directive establishes that paternity leave shall be paid at the national sick pay level (EU Directive 2019/1158 recital 30). In this regard, the Directive encourages fathers’ to take up paternity leave and the “early creation of a bond between fathers and children” (Directive 2019/1158 recital 19).

With regard to parental leave, article 5 of the EU Directive 2019/1158 sets rules aiming at sharing parental responsibilities. To this end, it is designed on Directive 2010/18/EU but attempts to promote and grant fortified already foreseen rights and to introduce new ones. In fact, it differentiate from the repealed 2010/18/EU Directive on the fact that not only provides the right for each worker to take four months paid parental leave, but it also sets to two months the non-transferable leave between parents. In addition, the new designed EU Directive 2019/1158 ensures more flexibility for parents by giving the rights to work on a part-time basis or by alternating periods of work and periods of leave until the child reaches the age of eight.

In EU labour law, before the adoption of the EU Directive 2019/1158, there were no provisions granting carers’ leave. This right is now given by article 6 of the Directive and aims at providing workers with caring responsibilities “greater opportunities to remain in the workforce” (EU Directive 2019/1158, preamble, recital 27). In this regard, it provides that workers with caring responsibilities have the right to leave (for caring reasons) five working days per year.

The Directive 2019/1158 provides also rights related to flexible working arrangements for workers who are parents or carers. the Directive implies that both working parents and carers will be allowed to design their working schedule, reduce working hours and, if needed, work remotely for complying with family needs (Directive (EU) 2019/1158 article 3). With these provisions, parents and carers shall be encouraged to stay in the labour market (Directive (EU) 2019/1158, preamble, recital 34). Member States by transposing the Directive into their national legislation, are expected to grant that parents and carers with children's of at least eight years, have the right of requesting working flexibility (Directive (EU) 2019/1158 article 9). Any refusal or postponement of the employer must be justified. At the end of the agreed flexible period, the worker is entitled to return to the original working pattern.

EU Directives set the results to be achieved but Member States are allowed to provide more favorable options to workers.

See also[]

- Annual leave

- Council of the European Union

- Economic and Monetary Union

- Economy of the European Union

- Employment

- EU Law

- European Commission

- European Internal Market

- European labour Law

- European Parliament

- European Single Market

- Four-day workweek

- Freedom of movement for workers in the European Union

- Gender balance

- List of holidays by country

- List of minimum annual leave by country

- Paid time off

- Public holidays in the European Union

- Six-hour day

- Work-life balance in Germany

- Work-life balance in the United States

- Work–life interface

References[]

- ^ Advancing work–life balance with EU Funds. A model for integrated gender-responsive interventions. © European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020 at p.7

- ^ Fleetwood, Steve (March 2007). "Re-thinking work–life balance: editor's introduction". The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 18 (3): 351–359. doi:10.1080/09585190601165486. ISSN 0958-5192. S2CID 154029625.

- ^ "Cornax Merel (2019) The potential contribution of the EU directive on work-life balance for parents and carers".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Cunningham, M. (2008). "Changing attitudes toward the male breadwinner, female homemaker family model: influences of women's employment and education over the lifecourse". Social Forces. 87 (1): 299–323. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0097. S2CID 144490888.

- ^ Greenhaus, Jeffrey (2003). "The relation between work–family balance and quality of life". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 63 (3): 510–531. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8.

- ^ "Indicators of Job Quality in the European Union, European Parliament" (PDF). 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "European Commission, 2017" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "European Commission, 2017" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jaspers et al. ‘European Labour Law’. Intersentia Publishing nv (2019): 499. © The editors and contributors severally 2019

- ^ Jaspers et al. ‘European Labour Law’. Intersentia Publishing nv (2019): 499-503. © The editors and contributors severally 2019

- ^ "Advancing work–life balance with EU Funds. A model for integrated gender-responsive interventions". European Institute for gender equality, 2020

- ^ "Eurostat 2020".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "European Council, 2000".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ ""The Open Method of Coordination", European Parliament, 2014" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Kok Report, 2004 "Facing the challenge - The Lisbon strategy for growth and employment"".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Europe 2020 Strategy" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment, 2020".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Council Directive 2010/18/EU of 8 March 2010 implementing the revised Framework Agreement on parental leave concluded by BUSINESSEUROPE, UEAPME, CEEP and ETUC and repealing Directive 96/34/EC (Text with EEA relevance)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Council Directive 96/34/EC of 3 June 1996 on the framework agreement on parental leave concluded by UNICE, CEEP and the ETUC".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Council Directive 97/81/EC of 15 December 1997 concerning the Framework Agreement on part-time work concluded by UNICE, CEEP and the ETUC - Annex : Framework agreement on part-time work".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Directive 97/81/EC, annex, clause 5". 20 January 1998.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Directive (EU) 2019/1158 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on work-life balance for parents and carers and repealing Council Directive 2010/18/EU".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- Work–life balance in Europe

- Politics of the European Union

- European Union labour law

- European Union