Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Geoffrey DeGraff 28 December 1949[1] Long Island, New York |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Nationality | American |

| School | Theravāda |

| Lineage | Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand |

| Education | Oberlin College |

| Order | Dhammayuttika Nikaya |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Ajahn Fuang Jotiko |

| Ordination | 7 November 1976, aged 26 (44 years ago)[1] |

| Post | Abbot of Metta Forest Monastery (since 1993) |

| Website | dhammatalks |

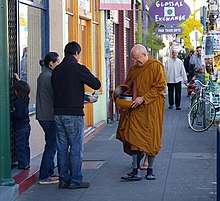

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (also known as Ajahn Geoff; born 28 December 1949) is an American Buddhist monk. Belonging to the Thai Forest Tradition, for 10 years he studied under the forest master Ajahn Fuang Jotiko (himself a student of Ajahn Lee). Since 1993 he has served as abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery in San Diego County, California — the first monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition in the US — which he cofounded with Ajahn Suwat Suvaco.[2]

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu is perhaps best known for his translations of the Dhammapada and the Sutta Pitaka — almost 1000 suttas in all — providing free of charge the majority of the sutta translations initially for the reference website Access to Insight[3] and since it was frozen to new input in 2013, on his website,[4] as well as translations from the dhamma talks of the Thai forest ajahns. He has also authored several dhamma-related works of his own, and has compiled study-guides of his Pali translations.[5]

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladharās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biography[]

| Part of a series on |

| Western Buddhism |

|---|

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2016) |

Early life[]

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu was born Geoffrey DeGraff in 1949 and was introduced to the Buddha's teaching on the Four Noble Truths as a high schooler, during a plane ride from the Philippines.[5] Tricycle writes: "he grew up 'a very serious, independent little kid", spending his early childhood on a potato farm on Long Island, New York, and later living in the suburbs of Washington, D.C.[6]

Time at Oberlin[]

At Oberlin College in the early 1970s, "he eschewed campus political activism because 'I didn't feel comfortable following a crowd.' For him, the defining issue of the day wasn't Vietnam, but a friend's attempted suicide."[6] Ṭhānissaro took a religious studies class when he found out there was meditation involved. Ṭhānissaro writes: "I saw it as a skill I could master, whereas Christianity only had prayer, which was pretty hit-or-miss."[6]

First trip to Thailand[]

After graduating in 1971 with a degree in European Intellectual History from Oberlin College, he traveled on a university fellowship to Thailand.[7] After a two-year search Ṭhānissaro found a forest teacher — Ajahn Fuang Jotiko, a Kammatthana monk who studied under Ajahn Lee Dhammadaro.

After a brief stay with the teacher was cut short by malaria, he returned to the U.S. to weigh the merits of academia and monasticism.[citation needed]

Return to Thailand[]

Ṭhānissaro states that when he returned to Thailand he originally planned on becoming a monk tentatively for five years. When he said that he wanted to be ordained, Ajahn Fuang made him promise to either "succeed in the meditation or die in Thailand. There was to be no equivocating."[2] Ṭhānissaro felt certain upon hearing this.

Time with Ajahn Fuang[]

By Ṭhānissaro's third year ordained as a monk, he became Ajahn Fuang's attendant. Ajahn Fuang's case of psoriasis deteriorated. It reached a point where Thānissaro had to be at his side constantly.

Ṭhānissaro writes: "When I talked with Ajahn Fuang about going back to the West, about taking the tradition to America, he was very explicit. 'This will probably be your life's work,' he said. He felt, as many teachers have, that the forest tradition would die out in Thailand but would then take root in the West."[2]

Posting at Wat Metta[]

Before Ajahn Fuang's death in 1986, he expressed his wish for Ajahn Geoff to become abbot of Wat Dhammasathit. Ṭhānissaro says that in spite of Ajahn Fuang's wish there were a lot of people maneuvering to become abbot.[citation needed] After Ajahn Fuang died, Wat Dhammasathit had already come far from the outlying forest hermitage that Taan Geoff had once arrived at. Ṭhānissaro said: "Ajahn Fuang said to keep moving; this is not a tradition that works well in big groups." Taan Geoff declined the offer of abbot of Wat Dhammasathit, which came with strings attached, and no authority since he was a Westerner in a monastery founded by and for Thai monks.

Instead of taking that position, he travelled to San Diego County in 1991, upon request of Ajahn Suwat Suvaco, where he helped start Metta Forest Monastery.[5] He became abbot of the monastery in 1993.[8] In 1995, Ajahn Geoff became the first American-born, non-Thai bhikkhu to be given the title, authority, and responsibility of Preceptor (Upajjhaya) in the Dhammayut Order. He also serves as Treasurer of that order in the United States.

Teachings[]

Classical Buddhist modernism[]

Views on commentarial meditation practice[]

Ṭhānissaro rejects the practice of kasina outlined in the Visuddhimagga, and warns against forms of "deep jhana" practiced by contemporary meditation teachers who draw from the commentaries. Ṭhānissaro calls these meditations "wrong concentration", and says that they have no basis in the Pali Canon, which he argues should be considered ultimately authoritative.[9][10]

Forest as teacher and Buddhist counterculture[]

Ṭhānissaro talks about the importance of the forest to give rise to the qualities of mind necessary to succeed in Buddhist practice.[11] Barbara Roether writes:

Like Thoreau, Thanissaro Bhikkhu has founded a kind of Walden as the Abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery near San Diego, the first Thai forest tradition monastery in this country. Just as the utopian movement in America was sparked by the advent of the industrial revolution, the forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism was developed in Thailand around the turn of the century by Ajahn Mun Bhuridatto in reaction to the increasing urbanization of the Buddhist monastic communities there. Forest monks abandoned the heavy social demands of the city and devoted themselves to meditation instead.[2]

Unbinding with reference to nibbana[]

Ṭhānissaro and others use the term unbinding when discussing nibbana.[12][13]

On the self[]

He has said that our sense of self is an activity, and a strategy for avoiding suffering and maximizing happiness.[14]

Achieving true happiness[]

He has said "You let go of the grosser forms of happiness, the grosser strategies for happiness, and get used to more and more refined ones. And they finally take you to the point where there's no course left but to let go of strategies. All strategies..... This is the way to true happiness." [15]

Publications[]

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu's publications include:[16]

- Translations of Ajahn Lee's meditation manuals from the Thai

- With Each and Every Breath, a basic meditation guide

- Handful of Leaves, a five-volume anthology of sutta translations

- The Buddhist Monastic Code, a two-volume reference handbook on the topic of monastic discipline

- Wings to Awakening, a study of the factors taught by Gautama Buddha as being essential for awakening

- The Mind Like Fire Unbound, an examination of Upādāna (clinging) and Nibbana (Nirvana) in terms of contemporary philosophies of fire

- The Paradox of Becoming, an extensive analysis on the topic of becoming as a causal factor of dukkha (suffering)

- The Shape of Suffering, a study of patittasamuppāda (dependent co-arising) and its relationship to the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path

- Skill in Questions, a study of how the Buddha's fourfold strategy in answering questions provides a framework for understanding the strategic purpose of his teachings

- Noble Strategy, The Karma of Questions, Purity of Heart, Head & Heart Together, and Beyond All Directions, collections of essays on Buddhist practice

- Meditations (1-10), collections of transcribed Dhamma talks

- Dhammapada: A Translation, a collection of verses by the Buddha

- And as co-author, a college-level textbook, Buddhist Religions: A Historical Introduction

Aside from Buddhist Religions, all of the books and articles and talks mentioned above are available for free distribution on Bhikkhu's website dhammatalks.org.

Some teaching locations[]

- Metta Forest Monastery

- Portland Friends of Dhamma

- Barre Center for Buddhist Studies

- The Cambridge Insight Meditation Center

- Insight Meditation Center

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b พระภาวนาวิธานปรีชา วิ. (เจฟฟรีย์ ฐานิสฺสโร).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Roether 1995.

- ^ "Access to Insight: Translators". Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ^ https://www.dhammatalks.org/suttas/ati.html

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Orloff, Rich (2004), "Being a Monk: A Conversation with Thanissaro Bhikkhu", Oberlin Alumni Magazine, 99 (4)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Survival Tactics for the Mind: Thanissaro Bhikkhu speaks about tradition, sexism, and following the Buddha's rules". Tricycle. Winter 1998.

- ^ "About; Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Phra Ajaan Geoff)". Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ "Contributing Authors and Translators: Biographical Notes". Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- ^ Quli 2008.

- ^ "Jhanas, Concentration, and Wisdom". DhammaTalks.net. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "The Customs of the Noble Ones". Access to Insight. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ https://www.dhammatalks.org/suttas/DN/DN16.html

- ^ http://www.vipassana.co.uk/canon/khuddaka/udana/ud8-3.php

- ^ https://www.dhammatalks.org/books/Meditations2/Section0040.html

- ^ https://www.dhammatalks.org/books/Meditations2/Section0040.html at end

- ^ Bullitt, John (2007), "Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff)", Access to Insight, retrieved August 31, 2010

Bibliography[]

- Quli, Natalie (2008), "Multiple Buddhist Modernisms: Jhana in Convert Theravada" (PDF), Pacific World: 225–249

- Roether, Barbara (Fall 1995), Exile Spirit: A profile of Thanissaro Bhikkhu and the Metta Forest Monastery, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

- Survival Tactics for the Mind: Thanissaro Bhikkhu speaks about tradition, sexism, and following the Buddha's rules, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Winter 1998, archived from the original on 2015-09-09

- Shankman, Richard (2008), The Experience of Samadhi: An In-depth Exploration of Buddhist Meditation (PDF), Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1-59030-521-8

- Thanissaro (2010), The Customs of the Noble Ones, Access To Insight

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu |

- 1949 births

- American expatriates in the Philippines

- Buddhist translators

- Converts to Buddhism

- Living people

- Oberlin College alumni

- Theravada Buddhism writers

- Theravada Buddhist monks

- American Theravada Buddhists

- American Buddhist monks

- Translators from Pali