Agomelatine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Melitor, Thymanax, Valdoxan, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 1%[1] |

| Protein binding | 95%[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver (90% CYP1A2 and 10% CYP2C9)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 1–2 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Kidney (80%, mostly as metabolites)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.157.896 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 243.306 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Agomelatine is an atypical antidepressant used to treat major depressive disorder.[5] One review found that it is as effective as other antidepressants with similar discontinuation rates overall but less discontinuations due to side effects.[5][6] Another review also found it was similarly effective to many other antidepressants.[7]

Common side effects include weight gain, fatigue, liver problems, nausea, headaches, and anxiety.[8][9] Due to potential liver problems ongoing blood tests are recommended.[10] Its use is not recommended in people with dementia or over the age of 75.[8] There is tentative evidence that it may have fewer side effects than some other antidepressants.[5] It works by stimulating melatonin receptors and blocking serotonin receptors.[10]

Agomelatine was approved for medical use in Europe in 2009 and Australia in 2010.[10] Its use is not approved in the United States and efforts to get approval were ended in 2011.[10] It was developed by the pharmaceutical company Servier.[10]

Medical uses[]

Major depressive disorder[]

Agomelatine is used for the treatment of major depressive episodes in adults in Europe.[11] Ten placebo controlled trials have been performed to investigate the short term efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder. At the end of treatment, significant efficacy was demonstrated in six of the ten short-term double-blind placebo-controlled studies.[11] Two were considered "failed" trials, as comparators of established efficacy failed to differentiate from placebo. Efficacy was also observed in more severely depressed patients in all positive placebo-controlled studies.[11] The maintenance of antidepressant efficacy was demonstrated in a relapse prevention study.[11] One meta-analysis found agomelatine to be as effective as standard antidepressants.[12]

A meta-analysis found that agomelatine is effective in treating severe depression. Its antidepressant effect is greater for more severe depression. In people with a greater baseline score (>30 on HAMD17 scale), the agomelatine-placebo difference was of 4.53 points.[13] Controlled studies in humans have shown that agomelatine is at least as effective as the SSRI antidepressants paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, and fluoxetine in the treatment of major depression.[14] A 2018 meta-study comparing 21 antidepressants found agomelatine was one of the more tolerable, yet effective antidepressants.[7]

However, the body of research on agomelatine has been substantially affected by publication bias, prompting analyses which take into account both published and unpublished studies.[6][15][16] These have confirmed that agomelatine is approximately as effective as more commonly used antidepressants (e.g. SSRIs), but some qualified this as "marginally clinically relevant",[16] being only slightly above placebo.[15][16] According to a 2013 review, agomelatine did not seem to provide an advantage in efficacy over other antidepressants for the acute-phase treatment of major depression.[17]

Use in special populations[]

It is not recommended in Europe for use in children and adolescents below 18 years of age due to a lack of data on safety and efficacy.[11] However, a study reported in September, 2020, showed greater efficacy vs. placebo for agomelatine 25mg per day in youth age 7-18 years.[18] Only limited data is available on use in elderly people ≥ 75 years old with major depressive episodes.[11]

It is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[8]

Contraindications[]

Agomelatine is contraindicated in patients with kidney or liver impairment.[11] According to information disclosed by Servier in 2012, guidelines for the follow-up of patients treated with Valdoxan have been modified in concert with the European Medicines Agency. As some patients may experience increased levels of liver enzymes in their blood during treatment with Valdoxan, doctors have to run laboratory tests to check that the liver is working properly at the initiation of the treatment and then periodically during treatment, and subsequently decide whether to pursue the treatment or not.[19] No relevant modification in agomelatine pharmacokinetic parameters in patients with severe renal impairment has been observed. However, only limited clinical data on its use in depressed patients with severe or moderate renal impairment with major depressive episodes is available. Therefore, caution should be exercised when prescribing agomelatine to these patients.[11]

Adverse effects[]

Agomelatine does not alter daytime vigilance and memory in healthy volunteers. In depressed patients, treatment with the drug increased slow wave sleep without modification of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep amount or REM latency.[20] Agomelatine also induced an advance of the time of sleep onset and of minimum heart rate. From the first week of treatment, onset of sleep and the quality of sleep were significantly improved without daytime clumsiness as assessed by patients.[1][11]

Agomelatine appears to cause fewer sexual side effects and discontinuation effects than paroxetine.[1]

- Hyperhidrosis (excess sweating that is not proportionate to the ambient temperature)

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Back pain

- Fatigue

- Increased ALAT and ASAT (liver enzymes)

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Somnolence

- Insomnia

- Migraine

- Anxiety

- Paraesthesia (abnormal sensations [e.g. itching, burning, tingling, etc.] due to malfunctioning of the peripheral nerves)

- Blurred vision

- Eczema

- Pruritus (itching)

- Urticaria

- Agitation

- Irritability

- Restlessness

- Aggression

- Nightmares

- Abnormal dreams

- Mania

- Hypomania

- Suicidal ideation

- Suicidal behaviour

- Hallucinations

- Steatohepatitis

- Increased GGT and/or alkaline phosphatase

- Liver failure

- Jaundice

- Erythematous rash

- Face oedema and angioedema

- Weight gain or loss, which tends to be less significant than with SSRIs[23]

Dependence and withdrawal[]

No dosage tapering is needed on treatment discontinuation.[11] Agomelatine has no abuse potential as measured in healthy volunteer studies.[1][11]

Overdose[]

Agomelatine is expected to be relatively safe in overdose.[24]

Interactions[]

Agomelatine is a substrate of CYP1A2, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. Inhibitors of these enzymes, e.g. the SSRI antidepressant fluvoxamine, reduce its clearance and can therefore lead to an increase in agomelatine exposure.[1][21] There is also the potential for agomelatine to interact with alcohol to increase the risk of hepatotoxicity.[1][21]

Pharmacology[]

Pharmacodynamics[]

Agomelatine is a melatonin receptor agonist (MT1 (Ki 0.1 nM) and MT2 (Ki = 0.12 nM)) and serotonin 5-HT2C (Ki = 631 nM) and 5-HT2B receptor (Ki = 660 nM) antagonist.[25][26] Binding studies indicate that it has no effect on monoamine uptake and no affinity for adrenergic, histamine, cholinergic, dopamine, and benzodiazepine receptors, nor other serotonin receptors.[11]

Agomelatine resynchronizes circadian rhythms in animal models of delayed sleep phase syndrome.[27] By antagonizing 5-HT2C, it disinhibits/increases noradrenaline and dopamine release specifically in the frontal cortex. Therefore, it is sometimes classified as a norepinephrine–dopamine disinhibitor. It has no influence on the extracellular levels of serotonin. Agomelatine has shown an antidepressant-like effect in animal models of depression (learned helplessness test, despair test, chronic mild stress) as well as in models with circadian rhythm desynchronisation and in models related to stress and anxiety. In humans, agomelatine has positive phase shifting properties; it induces a phase advance of sleep, body temperature decline and melatonin onset.[11]

Antagonism of 5-HT2B is an antidepressant property agomelatine shares with several atypical antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole, which are themselves used as atypical antidepressants. 5-HT2B antagonists are currently being investigated for their usefulness in reducing cardiotoxicity of drugs as well as being effective in reducing headache. Hence this particular receptor antagonism of agomelatine is useful for its antidepressant effectiveness as well as reducing the drug's adverse effects.[28]

Chemistry[]

Structure[]

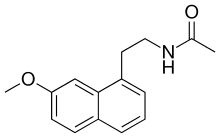

The chemical structure of agomelatine is very similar to that of melatonin. Where melatonin has an indole ring system, agomelatine has a naphthalene bioisostere instead.[29]

Synthesis[]

History[]

Agomelatine was discovered and developed by the European pharmaceutical company Servier Laboratories Ltd. Servier continued to develop the drug and conduct phase III trials in the European Union.

In March 2005, Servier submitted agomelatine to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) under the trade names Valdoxan and Thymanax.[34] On 27 July 2006, the Committee for Medical Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the EMA recommended a refusal of the marketing authorisation. The major concern was that efficacy had not been sufficiently shown, while there were no special concerns about side effects.[34] In September 2007, Servier submitted a new marketing application to the EMA.[35]

In March 2006, Servier announced it had sold the rights to market agomelatine in the United States to Novartis.[36] It was undergoing several phase III clinical trials in the US, and until October 2011 Novartis listed the drug as scheduled for submission to the FDA no earlier than 2012.[37] However, the development for the US market was discontinued in October 2011, when the results from the last of those trials became available.[38]

It received approval from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for marketing in the European Union in February 2009[11] and approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for marketing in Australia in August 2010.[1]

Research[]

Agomelatine has been found more effective than placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[39] Agomelatine was under development by Servier for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder and had reached phase III clinical trials for this indication, but in August 2017, Servier communicated that development for this indication is suspended.[40]

Agomelatine is also studied for its effects on sleep regulation. Studies report various improvements in general quality of sleep metrics, as well as benefits in circadian rhythm disorders.[6][27][41]

A 2019 review suggested no recommendations of agomelatine in support of, or against, its use to treat individuals with seasonal affective disorder.[42]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Valdoxan Product Information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Servier Laboratories Pty Ltd. 2013-09-23. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ "Valdoxan 25 mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Thymanax EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Valdoxan EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Guaiana G, Gupta S, Chiodo D, Davies SJ, Haederle K, Koesters M (December 2013). "Agomelatine versus other antidepressive agents for major depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008851.pub2. PMID 24343836.

- ^ a b c Taylor D, Sparshatt A, Varma S, Olofinjana O (March 2014). "Antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine: meta-analysis of published and unpublished studies". BMJ. 348: g1888. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1888. PMC 3959623. PMID 24647162.

- ^ a b Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ a b c British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 357–358. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "Product Information: Valdoxan, INN-agomelatine" (PDF). www.ema.europa.eu. European Medicines Agency. 13 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Norman, TR; Olver, JS (13 February 2019). "Agomelatine for depression: expanding the horizons?". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 20 (6): 647–656. doi:10.1080/14656566.2019.1574747. PMID 30759026. S2CID 73421269.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicine Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ Taylor D, Sparshatt A, Varma S, Olofinjana O (March 2014). "Antidepressant efficacy of agomelatine: meta-analysis of published and unpublished studies". BMJ. 348: g1888. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1888. PMC 3959623. PMID 24647162.

- ^ Montgomery SA, Kasper S (September 2007). "Severe depression and antidepressants: focus on a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled studies on agomelatine". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 22 (5): 283–91. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280c56b13. PMID 17690597. S2CID 21796064.

- ^ Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N (April 2012). "Efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and appraisal". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (3): 417–28. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001301. PMID 21859514.

- ^ a b Koesters M, Guaiana G, Cipriani A, Becker T, Barbui C (September 2013). "Agomelatine efficacy and acceptability revisited: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomised trials". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 203 (3): 179–87. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.120196. PMID 23999482.

- ^ a b c Howland RH (September 2011). "A benefit-risk assessment of agomelatine in the treatment of major depression". Drug Safety. 34 (9): 709–31. doi:10.2165/11593960-000000000-00000. PMID 21830835. S2CID 21808090.

- ^ Guaiana G, Gupta S, Chiodo D, Davies SJ, Haederle K, Koesters M (December 2013). "Agomelatine versus other antidepressive agents for major depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008851.pub2. PMID 24343836.

- ^ "Agomelatine Effective for Children, Adolescents With Depression". dgnews.docguide.com. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- ^ "Information about Valdoxan for patients". Servier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Quera Salva, Maria-Antonia; Vanier, Bernard; Laredo, Judith; Hartley, Sarah; Chapotot, Florian; Moulin, Catherine; Lofaso, Frédéric; Guilleminault, Christian (2007-05-04). "Major depressive disorder, sleep EEG and agomelatine: an open-label study". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (5): 691–696. doi:10.1017/S1461145707007754. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 17477886.

- ^ a b c d e Australian Medicines Handbook 2013. Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. 2013. ISBN 9780980579093.

- ^ a b c Joint Formulary Committee and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) 65. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0857110848.

- ^ Kennedy SH, Rizvi SJ (June 2010). "Agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: potential for clinical effectiveness". CNS Drugs. 24 (6): 479–99. doi:10.2165/11534420-000000000-00000. PMID 20192279. S2CID 41069663.

- ^ Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ Dridi D, Zouiten A, Mansour HB (June 2013). "Depression: chronophysiology and chronotherapy". Biological Rhythm Research. 45: 77–91. doi:10.1080/09291016.2013.797657. S2CID 84678381.

- ^ Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Dekeyne A, Newman-Tancredi A, Pasteau V, Rivet JM, Cussac D (September 2003). "The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 306 (3): 954–64. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.051797. PMID 12750432. S2CID 18753440.

- ^ a b Le Strat Y, Gorwood P (September 2008). "Agomelatine, an innovative pharmacological response to unmet needs". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 22 (7 Suppl): 4–8. doi:10.1177/0269881108092593. PMID 18753276. S2CID 29745284.

- ^ Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Dekeyne A, Newman-Tancredi A, Pasteau V, Rivet JM, Cussac D (September 2003). "The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 306 (3): 954–64. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.051797. PMID 12750432. S2CID 18753440.

- ^ Tinant B, Declercq JP, Poupaert JH, Yous S, Lesieur D (1994). "N-[2-(7-Methoxy-1-naphthyl)ethyl]acetamide, a potent melatonin analog". Acta Crystallogr. C. 50 (6): 907–910. doi:10.1107/S0108270193012922.

- ^ EP application 447285, Andrieux J, Houssin R, Yous S, Guardiola B, Lesieur D, "Naphthalene derivatives, procedure for their preparation and pharmaceutical compositions containing them.", published 1991-09-18, assigned to Adir

- ^ US granted 5225442, Andrieux J, Houssin R, Yous S, Guardiola B, Lesieur D, "Compounds having a naphthalene structure", issued 6 July 1993, assigned to Adir

- ^ Yous S, Andrieux J, Howell HE, Morgan PJ, Renard P, Pfeiffer B, Lesieur D, Guardiola-Lemaitre B (April 1992). "Novel naphthalenic ligands with high affinity for the melatonin receptor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 35 (8): 1484–6. doi:10.1021/jm00086a018. PMID 1315395.

- ^ Depreux P, Lesieur D, Mansour HA, Morgan P, Howell HE, Renard P, Caignard DH, Pfeiffer B, Delagrange P, Guardiola B (September 1994). "Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of novel naphthalenic and bioisosteric related amidic derivatives as melatonin receptor ligands". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 37 (20): 3231–9. doi:10.1021/jm00046a006. PMID 7932550.

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers on Recommendation for Refusal of Marketing Authorisation" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 18 November 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "CHMP Assessment Report for Valdoxan" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 20 November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ Bentham C (2006-03-29). "Servier and Novartis sign licensing agreement for agomelatine, a novel treatment for depression". Servier UK. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ "Clinical trials for agomelatine". ClinicalTrials.gov. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ Malone E (25 October 2011). "Novartis drops future blockbuster agomelatine". Scrip Intelligence. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011.

- ^ De Berardis D, Conti CM, Marini S, Ferri F, Iasevoli F, Valchera A, Fornaro M, Cavuto M, Srinivasan V, Perna G, Carano A, Piersanti M, Martinotti G, Di Giannantonio M (2013). "Is there a role for agomelatine in the treatment of anxiety disorders?A review of published data". International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 26 (2): 299–304. doi:10.1177/039463201302600203. PMID 23755745. S2CID 40152863.

- ^ "Agomelatine - Servier". Adis Insight.

- ^ "Valdoxan: A New Approach to The Treatment of Depression". Medical News Today. MediLexicon International Ltd. 2005-04-05. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ Nussbaumer-Streit, Barbara; Greenblatt, Amy; Kaminski-Hartenthaler, Angela; Van Noord, Megan G.; Forneris, Catherine A.; Morgan, Laura C.; Gaynes, Bradley N.; Wipplinger, Jörg; Lux, Linda J.; Winkler, Dietmar; Gartlehner, Gerald (17 June 2019). "Melatonin and agomelatine for preventing seasonal affective disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD011271. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011271.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6578031. PMID 31206585.

External links[]

- "Agomelatine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Genf interaction table- https://www.hug.ch/sites/interhug/files/structures/pharmacologie_et_toxicologie_cliniques/carte_cytochromes_2016_final.pdf

- 5-HT2C antagonists

- Acetamides

- Antidepressants

- Laboratoires Servier

- Melatonin receptor agonists

- Naphthol ethers

- Phenethylamines