Al-Hasakah Governorate

Al-Hasakah Governorate

محافظة الحسكة | |

|---|---|

Map of Syria with Al-Hasakah Governorate highlighted | |

| Coordinates (Hasakah): 36°30′N 40°54′E / 36.5°N 40.9°ECoordinates: 36°30′N 40°54′E / 36.5°N 40.9°E | |

| Country | Syria |

| Capital | Al-Hasakah |

| Districts | 4 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Major General Jaiz Swadet al-Hamoud al-Musa |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23,334 km2 (9,009 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 1,512,000[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | SY-HA |

| Main language(s) | Arabic, Kurdish, Syriac, Armenian |

| Ethnicities | Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians & Yazidis |

Al-Hasakah Governorate (Arabic: محافظة الحسكة, romanized: Muḥāfaẓat al-Ḥasakah, Classical Syriac: ܗܘܦܪܟܝܐ ܕܚܣܟܗ, romanized: Huparkiyo d'Ḥasake, also known as Classical Syriac: ܓܙܪܬܐ, romanized: Gozarto) is one of the fourteen governorates (provinces) of Syria. It is located in the far north-east corner of Syria and distinguished by its fertile lands, plentiful water, natural environment, and more than one hundred archaeological sites. It was formerly known as Al-Jazira Province. Prior to the Syrian Civil War nearly half of Syria's oil was extracted from the region.[2] It is the lower part of Upper Mesopotamia.

Geography[]

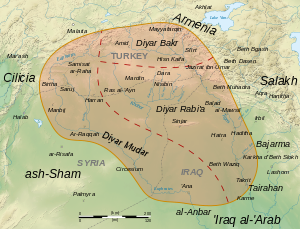

During the Abbasid era, the area that makes this province used to be part of the Diyar Rabi'a administrative unit, corresponding to the southern part of Upper Mesopotamia. Kurdistan did not include the lands of Syrian Jazira.[note 1][3] The Treaty of Sèvres' putative Kurdistan did not include any part of today's Syria.[4]

Political history[]

The French, following the Ottoman policies which encouraged the nomadic tribes to become sedentary, established several villages and towns since the beginning of their rule.[5] Hasakah was founded in 1922, Qamishli in 1926.[6] In the late 1930s a small but vigorous separatist movement emerged in Qamishli. With some support from French Mandate authorities, the movement actively lobbied for autonomy directly under French rule and its separation from Syria on the ground that the majority of the inhabitants were not Arabs. Syrian nationalists saw the movement as a profound threat to their eventual rule. The Syrian nationalists allied with local Arab Shammar tribal leader and Kurdish tribes. They together attacked the Christian movement in many towns and villages. Local Kurdish tribes who were allies of Shammar tribe sacked and burned the Assyrian (Syriac) town of Amuda.[7][8] In 1941, the Assyrian (Syriac) community of al-Malikiyah was subjected to a vicious assault. Even though the assault failed, Assyrians (Syriacs) felt threatened and left in large numbers, and the immigration of Kurds from Turkey to the area converted al-Malikiya, al-Darbasiyah and Amuda to Kurdish-majority cities.

Between 1932 and 1939, a Kurdish-Assyrian autonomy movement emerged in Jazira. The demands of the movement were autonomous status similar to the Sanjak of Alexandretta, the protection of French troops, promotion of Kurdish language in schools and hiring of Kurdish officials. The movement was led by Michel Dome, mayor of Qamishli, Hanna Hebe, general vicar for the Syriac-Catholic Patriarch of Jazira, and the Kurdish notable Hajo Agha. Some Arab tribes supported the autonomists while others sided with the central government. In the legislative elections of 1936, autonomist candidates won all the parliamentary seats in Jazira and Jarabulus, while the nationalist Arab movement known as the National Bloc won the elections in the rest of Syria. After victory, the National Bloc pursued an aggressive policy toward the autonomists. In July 1937, armed conflict broke out between the Syrian police and the supporters of the movement. As a result, the governor and a significant portion of the police force fled the region and the rebels established local autonomous administration in Jazira.[9] In August 1937 a number of Assyrians in Amuda were killed by a pro-Damascus Kurdish chief.[10] In September 1938, Hajo Agha chaired a general conference in Jazira and appealed to France for self-government.[11] The new French High Commissioner, Gabriel Puaux, dissolved parliament and created autonomous administrations for Jabal Druze, Latakia and Jazira in 1939 which lasted until 1943.[12]

Demographics[]

Al-Hasakah Governorate's ethnic groups include Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians and Yazidis. The majority of the Arabs and Kurds in the region are Sunni Muslim. Between 20 and 30% of the people of Al-Hasakeh city are Christians of various churches and denominations (majority Syriac Orthodox).[13]

Until the beginning of the 20th century, al-Hasakah Governorate (then called Jazira province) was a “no man’s land” primarily reserved for the grazing land of nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes.[14] During the late days of the Ottoman Empire, large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia. The largest of these tribal groups was the Reshwan confederation, which was initially based in Adıyaman Province but eventually also settled throughout Anatolia. The Milli confederation, mentioned in 1518 onward, was the most powerful group and dominated the entire northern Syrian steppe in the second half of the 18th century. Danish writer C. Niebuhr who traveled to Jazira in 1764 recorded five nomadic Kurdish tribes (Dukurie, Kikie, Schechchanie, Mullie and Aschetie) and six Arab tribes (Tay, Kaab, Baggara, Geheish, Diabat and Sherabeh).[15] According to Niebuhr, the Kurdish tribes were settled near Mardin in Turkey, and paid the governor of that city for the right to graze their herds in the Syrian Jazira.[16][17] The Kurdish tribes gradually settled in villages and cities and are still present in the modern governorate).[18]

The demographics of northern Syria saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century when the Ottoman Empire (Turks) conducted ethnic cleansing of its Armenian and Assyrian Christian populations and some Kurdish tribes joined in the atrocities committed against them.[19][20][21] Many Assyrians fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[22][23][24] During WWI and subsequent years, thousands of Assyrians fled their homes in Anatolia after massacres. After that, massive waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey due to conflict with Kemalist authorities and settled in Syria, where they were granted citizenship by the French Mandate authorities.[25] The number of Kurds settled in the Jazira province during the 1920s was estimated at 20,000 people.[26] Starting in 1926, the region witnessed another huge immigration wave of Kurds following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[27] Tens of thousands of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syria, and as usual, were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities.[25] This large influx of Kurds moved to Syria's Jazira province. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.[28] The French official reports show the existence of at most 45 Kurdish villages in Jazira prior to 1927. A new wave of refugees arrived in 1929.[29] The mandatory authorities continued to encourage Kurdish immigration into Syria, and by 1939, the villages numbered between 700 and 800.[29] French authorities were not opposed to the streams of Assyrians, Armenians or Kurds who, for various reasons, had left their homes and had found refuge in Syria. The French authorities themselves generally organized the settlement of the refugees. One of the most important of these plans was carried out in Upper Jazira in northeastern Syria where the French built new towns and villages (such as Qamishli) were built with the intention of housing the refugees considered to be “friendly”. This has encouraged the non-Turkish minorities that were under Turkish pressure to leave their ancestral homes and property, they could find refuge and rebuild their lives in relative safety in neighboring Syria.[30] Consequently, the border areas in al-Hasakah Governorate started to have a Kurdish majority, while Arabs remained the majority in river plains and elsewhere.[31]

In 1939, French mandate authorities reported the following population numbers for the different ethnic and religious groups in al-Hasakah governorate.[32]

| District | Arab | Kurd | Assyrian | Armenian | Yezidi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasakah city centre | 7133 | 360 | 5700 | 500 | |

| Tel Tamer | 8767 | ||||

| Ras al-Ayn | 2283 | 1025 | 2263 | ||

| Shaddadi | 2610 | 6 | |||

| Tel Brak | 4509 | 905 | 200 | ||

| Qamishli city centre | 7990 | 5892 | 14,140 | 3500 | 720 |

| Amuda | 11,260 | 1500 | 720 | ||

| Derbasiyeh | 3011 | 7899 | 2382 | 425 | |

| Shager Bazar | 380 | 3810 | 3 | ||

| Ain Diwar | 3608 | 900 | |||

| Derik (later renamed al-Malikiyah) | 44 | 1685 | 1204 | ||

| Mustafiyya | 344 | 959 | 50 | ||

| Derouna Agha | 570 | 5097 | 27 | ||

| Tel Koger (later renamed Al-Yaarubiyah) | 165 | ||||

| Nomadic | 25,000 | ||||

| Totals | 54,039 | 42,500 | 36,942 | 4200 | 1865 |

The population of the governorate reached 155,643 in 1949, including about 60,000 Kurds.[31] These continuous waves swelled the number of Kurds in the area who represented 30% of the Jazira population in a 1939 French authorities census.[32] In 1953, French geographers Fevret and Gibert estimated that out of the total 146,000 inhabitants of Jazira, agriculturalist Kurds made up 60,000 (41%), semi-sedentary and nomad Arabs 50,000 (34%), and a quarter of the population were Christians.[33]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 44,153 | — |

| 1933 | 64,886 | +47.0% |

| 1935 | 94,596 | +45.8% |

| 1937 | 98,144 | +3.8% |

| 1938 | 103,514 | +5.5% |

| 1939 | 106,052 | +2.5% |

| 1940 | 126,508 | +19.3% |

| 1942 | 136,107 | +7.6% |

| 1943 | 146,001 | +7.3% |

| 1946 | 151,137 | +3.5% |

| 1950 | 159,300 | +5.4% |

| 1953 | 232,104 | +45.7% |

| 1960 | 351,661 | +51.5% |

| 1970 | 468,506 | +33.2% |

| 1981 | 669,756 | +43.0% |

| 2004 | 1,275,118 | +90.4% |

| 2011 | 1,512,000 | +18.6% |

Censuses of 1943 and 1953[]

| Religious group | Population (1943) |

Percentage (1943) |

Population (1953) |

Percentage (1953) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | Sunni Muslims | 99,665 | 68.26% | 171,058 | 73.70% |

| Other Muslims | 437 | 0.30% | 503 | 0.22% | |

| Christians | Assyrians (Syriac Christians) | 31,764 | 21.76% | 42,626 | 18.37% |

| Armenians | 9,788 | 6.70% | 12,535 | 5.40% | |

| Other churches | 944 | 0.65% | 1,283 | 0.55% | |

| Total Christians | 42,496 | 29.11% | 56,444 | 24.32% | |

| Jews | 1,938 | 1.33% | 2,350 | 1.01% | |

| Yazidis | 1,475 | 1.01% | 1,749 | 0.75% | |

| TOTAL | Al-Jazira province | 146,001 | 100.0% | 232,104 | 100.0% |

Among the Sunni Muslims, mostly Kurds and Arabs, there were about 1,500 Circassians in 1938.[36]

Current demographics[]

The inhabitants of al-Hasakah governorate are composed of different ethnic and cultural groups, the larger groups being Arabs and Kurds in addition to a significant large number of Assyrians and a smaller number of Armenians.[37] The population of the governorate, according to the country's official census, was 1,275,118, and was estimated to be 1,377,000 in 2007, and 1,512,000 in 2011.

According to the National Association of Arab Youth, there are 1717 villages in Al-Hasakah province: 1161 Arab villages, 453 Kurdish villages, 98 Assyrian villages and 53 with mixed populations from the aforementioned ethnicities.[38]

| Arab villages | 1161 |

| Kurdish villages | 453 |

| Assyrian villages | 98 |

| Mixed Arab-Kurdish villages | 48 |

| Mixed villages | 3 |

| Mixed villages | 2 |

| Total | 1717 |

Today, Arabs comprise the largest demographic group and mostly live in the city of al-Hasaka and its south and east countryside, with smaller presence in the north and west countryside. Kurds are the second largest group, with thousands living in villages and towns in the north, northeast, and northwest countryside. Assyrians live mostly in the north and northeast regions of al-Hasaka, especially in Tell Tamer but also in Qamishli and al-Malikiyah.[39] In 2013 there was en estimated 200,000 Assyrians in Hasakah province [40]

Cities, towns and villages[]

This list includes all cities, towns and villages with more than 5,000 inhabitants. The population figures are given according to the 2004 official census:[41]

| English Name | Population | District |

|---|---|---|

| Al-Hasakah | 188,160 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Qamishli | 184,231 | Qamishli District |

| Ras al-Ayn | 29,347 | Ras al-Ayn District |

| Amuda | 26,821 | Qamishli District |

| Al-Malikiyah | 26,311 | Al-Malikiyah District |

| Al-Qahtaniyah | 16,946 | Qamishli District |

| Al-Shaddadi | 15,806 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Al-Muabbada | 15,759 | Al-Malikiyah District |

| Al-Sabaa wa Arbain | 14,177 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Al-Manajir | 12,156 | Ras al-Ayn District |

| Al-Darbasiyah | 8,551 | Ras al-Ayn District |

| Tell Tamer | 7,285 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Al-Jawadiyah | 6,630 | Al-Malikiyah District |

| Mabrouka | 6,325 | Ras al-Ayn District |

| Al-Yaarubiyah | 6,066 | Al-Malikiyah District |

| Tell Safouk | 5,781 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Tell Hamis | 5,161 | Qamishli District |

| Al-Tweinah | 5,062 | Al-Hasakah District |

| Al-Fadghami | 5,062 | Al-Hasakah District |

Districts and sub-districts[]

The governorate is divided into four districts (manatiq). The districts are further divided into 16 sub-districts (nawahi):

|

Archaeology[]

The Khabur River, which flows through al-Hasakah for 440 kilometres (270 mi), witnessed the birth of some of the earliest civilizations in the world, including those of Akkad, Assyria, Aram, the Hurrians and Amorites. The most prominent archaeological sites are:

- Hamoukar:considered by some archaeologists to be the oldest city in the world

- Tell Halaf: Excavations have revealed successive civilization levels, Neolithic glazed pottery and basalt sculptures.

- Tell Brak: Situated halfway between al-Hasakah city and the frontier town of Qamishli. Excavations in the tell have revealed the Uyun Temple and King Naram-Sin's palace-stronghold.

- Tell el Fakhariya

- : 15 layers of occupation have been identified.

- Tell Leilan: Excavations began in 1975 and have revealed many artefacts and buildings dating back to the 6th millennium BC such as a bazaar, temple, palace, etc.

Notes[]

- ^ Modern Curdistan is of much greater extent than the ancient Assyria, and is composed of two parts, the Upper and Lower. In the former is the province of Ardelaw, the ancient Arropachatis, now nominally a part of Irak Ajami, and belonging to the north-west division called Al Jobal. It contains five others, namely, Betlis, the ancient Carduchia, lying to the south and south-west of the lake Van. East and south-east of Betlis is the principality of Julamerick—south-west of it, is the principality of Amadia—the fourth is Jeezera ul Omar, a city on an island in the Tigris, and corresponding to the ancient city of Bezabde—the fifth and largest is Kara Djiolan, with a capital of the same name. The pashalics of Kirkook and Solimania also comprise part of Upper Curdistan. Lower Curdistan comprises all the level tract to the east of the Tigris, and the minor ranges immediately bounding the plains, and reaching thence to the foot of the great range, which may justly be denominated the Alps of western Asia.

A Dictionary of Scripture Geography (1846), John Miles.[3]

References[]

- ^ http://cbssyr.org/yearbook/2011/Data-Chapter2/TAB-3-2-2011.htm[permanent dead link]

- ^ Al Monitor, Syria's Oil Crisis, 2013, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/ru/originals/2013/02/syria-oil-crisis.html# Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b John R. Miles (1846). A Dictionary of Scripture Geography. Fourth edition. J. Johnson & Son, Manchester. p. 57.

- ^ David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 137. ISBN 9781850434160.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. pp. 146–147. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ Schmidinger, Thomas (2017-03-22). Krieg und Revolution in Syrisch-Kurdistan: Analysen und Stimmen aus Rojava (in German). Mandelbaum Verlag. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-85476-665-0.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 159. ISBN 9780838639429.

- ^ Keith David Watenpaugh (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. p. 270. ISBN 9781400866663.

- ^ Romano, David; Gurses, Mehmet (2014). Conflict, Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 146.

- ^ McDowell, David (2004). A modern history of the Kurds. Tauris. p. 471.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ "Al-Hasakeh Governorate profile" (PDF). www.acaps.org.

- ^ Algun, S., 2011. Sectarianism in the Syrian Jazira: Community, land and violence in the memories of World War I and the French mandate (1915- 1939). Ph.D. Dissertation. Universiteit Utrecht, the Netherlands. Pages 18. Accessed on 8 December 2019.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 419.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 0415072654.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 389.

- ^ Stefan Sperl, Philip G. Kreyenbroek (1992). The Kurds a Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-203-99341-1.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2007). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. ISBN 9781412835923. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown (2004). On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. p. 199. ISBN 9780953824861.

- ^ Lazar, David William, not dated A brief history of the plight of the Christian Assyrians* in modern-day Iraq Archived 2015-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. American Mesopotamian.

- ^ R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 24. ISBN 9781593334130.

- ^ "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162. ISBN 9780838639429.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- ^ Simpson, John Hope (1939). The Refugee Problem: Report of a Survey (First ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 458. ASIN B0006AOLOA.

- ^ Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- ^ McDowell, David (2005). A modern history of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1850434166.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. London: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4.

- ^ Tachjian Vahé, The expulsion of non-Turkish ethnic and religious groups from Turkey to Syria during the 1920s and early 1930s, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, [online], published on: 5 March 2009, accessed 09/12/2019, ISSN 1961-9898

- ^ Jump up to: a b La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique. André Gibert, Maurice Févret, 1953. La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique. In: Revue de géographie de Lyon, vol. 28, n°1, 1953. pp. 1-15; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/geoca.1953.1294 Accessed on 8 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Algun, S., 2011. Sectarianism in the Syrian Jazira: Community, land and violence in the memories of World War I and the French mandate (1915- 1939). Ph.D. Dissertation. Universiteit Utrecht, the Netherlands. Pages 11-12. Accessed on 8 December 2019.

- ^ Fevret, Maurice; Gibert, André (1953). "La Djezireh syrienne et son réveil économique". Revue de géographie de Lyon (in French) (28): 1–15. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ Hourani, Albert Habib (1947). Minorities in the Arab World. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 76.

- ^ Etienne, de Vaumas (1956). "La Djézireh". Annales de Géographie (in French). 65 (347): 64–80. doi:10.3406/geo.1956.14367. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ M. Proux, "Les Tcherkesses", La France méditerranéenne et africaine, IV, 1938

- ^ Syria - Sunnis

- ^ National Association of Arab Youth, 2012. Arab East Centre, London, 2012. Study of the demographic composition of al-Hasakah Governorate (in Arabic). Accessed on 26 December 2014.

- ^ "Arabs, Kurds, and the social ties that overcome political conflicts". Enab Baladi. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Die Welt: Die Christen in Syrien ziehen in die Schlacht". Die Welt (in German). 23 October 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2013-11-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links[]

- ehasakeh The First Complete website for Al-Hasakah news and services

- Al-Hasakah Governorate

- Governorates of Syria

- Assyrian geography

- Upper Mesopotamia