Albanians in Greece

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 443,550–600,000[1][2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Athens · Attica · Thessaloniki · Peloponnese · Boeotia · Epirus · Thessaly | |

| Languages | |

| Albanian, Greek | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunnism, Bektashism), Christianity (Orthodoxy, Catholicism), Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians, Albanians in Turkey and Albanians in North Macedonia |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

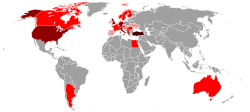

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

|

Christianity (Catholicism · Italo-Albanian Church · Albanian Greek-Catholic Church · Orthodoxy) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka · Istrian) · ) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Cham · Lab) |

|

History of Albania (Origin of the Albanians) |

Albanians in Greece (Albanian: Shqiptarët në Greqi; Greek: Αλβανοί στην Ελλάδα) are divided into distinct communities as a result of different waves of migration. Albanians first migrated into Greece during the late 13th century. The descendants of populations of Albanian origin who settled in Greece during the Middle Ages are the Arvanites, who have been fully assimilated into the Greek nation and self-identify as Greeks. Today, they still maintain their distinct subdialect of Tosk Albanian, known as Arvanitika.

The Cham Albanians are a group that lived Greece until 1945 and formerly inhabited coastal parts of Epirus, in northwestern Greece. They were expelled from Epirus during World War II after large parts of their population collaborated with the Axis occupation forces.[5] Greek Orthodox Albanian-speaking communities have been assimilated into the Greek nation.[6]

The Souliotes were a distinct subgroup of Cham Albanians who lived in the Souli region, and were known for the role in the Greek War of Independence.

Alongside these two groups, a large wave of economic migrants from Albania entered Greece after the fall of Communism (1991) and forms the largest expatriate community in the country. They form the largest migrant group in Greece. A portion of these immigrants avoid declaring as Albanian in order to avoid prejudices and exclusion. These Albanian newcomers may resort to self-assimilation tactics such as changing their Albanian name to Greek ones and, if they are Muslim their religion from Islam to Orthodoxy:[7] Some Albanians with a Muslim background may change their names in order to avoid problems in predominately Orthodox Christian Greece. Through this, they hope to attain easier access to visas and naturalisation.[8] After migration to Greece, most are baptized and integrated.

While Greece does not record ethnicity on censuses, Albanians form the largest ethnic minority and top immigrant population in the country.[9]

Native Albanian communities[]

Cham Albanians[]

Groups of Albanians are first recorded in Epirus during the late Middle Ages. Some of their descendants form the Cham Albanians, which formerly inhabited the coastal regions of Epirus, largely corresponding to Thesprotia. The Chams are primarily distinguished from other Albanian groups by their distinct dialect of Tosk Albanian, the Cham dialect, which is among the most conservative of the Albanian dialects.[citation needed] During the rule of the Ottoman Empire in Epirus, many Chams converted to Islam, while a minority remained Greek Orthodox.

When Epirus joined Greece in 1913, following the Balkan Wars, Muslim Chams lost the privileged status they enjoyed during Ottoman rule and were subject to discrimination from time to time. During World War II, large parts of the Muslim Chams collaborated with the Axis occupation forces, committing atrocities against the local population.[5] In 1944, when the Axis withdrew, many Muslim Chams fled to Albania or were forcibly expelled by the EDES resistance group. This event is known as the expulsion of Cham Albanians.

Communities of Albanian descent[]

Southern Greece[]

The Arvanites are by a community composed of the Southern Albanian dialectological group of Arvanitika speakers, known as Arvanites. They are a population group in Greece who traditionally speak Arvanitika, a form of Tosk Albanian. They settled in Greece during the late Middle Ages and were the dominant population element of some regions in the south of Greece until the 19th century.[10] Arvanites today self-identify as Greeks and have largely assimilated into mainstream Greek culture, they retain their dialect Arvanitika and cultural similarities with Albanians, but refuse any national connection with them and do not consider themselves an ethnic minority.[11][12] Arvanitika is endangered due to language shift towards Greek and large-scale internal migration to the cities in recent decades. The Arvanites are not considered an ethnic minority within Greece.

Northwestern Greece[]

The small Arvanite-speaking communities in Epirus and the Florina regional unit are considered part of the Greek nation as well.[13]

A small community is located in the Ioannina regional unit, where they form a majority in two villages of the Konitsa district.[14] This community includes the village of Plikati.[15] Although they are sometimes called Arvanites, their dialects are part of Tosk Albanian rather than Arvanitika. This population speaks the Lab branch of the Albanian language. The city of Ioannina in the past had a substantial minority of Albanian-speakers, where a dialect intermediate between Cham and Lab was spoken.[16] During Ottoman era the Albanian minority in the kaza of Ioannina did not consist of native families but was limited to a number of Ottoman public servants.[17]

Another small group of Albanian-speakers, speakers of a Northern Tosk Albanian dialect is to be found in the villages Drosopigi, Flampouro, Lechovo in Florina regional unit.[18]

Western Thrace[]

Another small group is to be found in northeastern Greece, in Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace along the border with Turkey, as a result of migration during the early 20th century. They speak the Northern Tosk subbranch of Tosk Albanian and are descendants of the Orthodox Albanian population of Eastern Thrace who were forced to migrate during the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s.[19][20] They are known in Greece as Arvanites, a name applied to all groups of Albanian origin in Greece, but which primarily refers to the southern dialectological group of Arbëreshë. The Albanian speakers of Western Thrace and Macedonia use the common Albanian self-appellation Shqiptar.[20]

Albanian immigrants[]

After the fall of the communist government in Albania in 1990, a large number of economic immigrants from Albania arrived in Greece, mostly illegally, and seeking employment. Recent economic migrants from Albania are estimated to account for 60–65% of the total number of immigrants in the country. According to the 2001 census, there are 443,550 holders of Albanian citizenship in Greece.[21] Some other estimates put their number closer to 600,000 when including temporary migrants, seasonal workers and undocumented individuals.[22] In this total, 189,000 Greeks of Albania, who hold Albanian nationality and are 'co-ethnics' or Vorioipirotes (from Northern Epirus), have also immigrated to Greece.[23] Since the Greek economic crisis started in 2011, the total number of Albanians in Greece has fluctuated.[24]

Albanians have a long history of Hellenisation, assimilation and integration in Greece. Despite social and political problems experienced by the wave of immigration in the 1980s and 1990s, Albanians have integrated better in Greece than other non-Greeks.[25] A portion of Albanian newcomers change their Albanian name to Greek ones and their religion, if they are not Christian, from Islam to Orthodoxy.[26] Even before emigration, some Albanians from the south of Albania adopt a Greek identity including name changes, adherence to the Orthodox faith, and other assimilation tactics in order to avoid prejudices against migrants in Greece. In this way, they hope to get valid visas and eventual naturalization in Greece.[27]

Notable people[]

See also[]

- Minorities in Greece

- Albanians in Kosovo

- Albanians in Serbia

- Albanians in Montenegro

References[]

- ^ Vathi, Zana. Migrating and settling in a mobile world: Albanian migrants and their children in Europe. Springer Nature, 2015.

- ^ Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. By Philip L. Martin, Susan Forbes Martin, Patrick Weil

- ^ Iosifides, Theodoros, Mari Lavrentiadou, Electra Petracou, and Antonios Kontis. "Forms of social capital and the incorporation of Albanian immigrants in Greece." Journal of ethnic and migration studies 33, no. 8 (2007): 1343-1361.

- ^ Lazaridis, Gabriella, and Iordanis Psimmenos. "Migrant flows from Albania to Greece: economic, social and spatial exclusion." In Eldorado or Fortress? Migration in Southern Europe, pp. 170-185. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2000.

- ^ a b Hermann Frank Meyer. Blutiges Edelweiß: Die 1. Gebirgs-division im zweiten Weltkrieg Bloodstained Edelweiss. The 1st Mountain-Division in WWII Ch. Links Verlag, 2008. ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1, p. 702

- ^ Hart, Laurie Kain (1999). "Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece". American Ethnologist. 26: 196. doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.1.196.

- ^ Armand Feka (2013-07-16). "Griechenlands verborgene Albaner". Wiener Zeitung. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

Er lächelt und antwortet in einwandfreiem Griechisch: ‚Ich bin eigentlich auch ein Albaner.‘

- ^ Lars Brügger; Karl Kaser; Robert Pichler; Stephanie Schwander-Sievers (2002). Umstrittene Identitäten. Grenzüberschreitungen zuhause und in der Fremde. Die weite Welt und das Dorf. Albanische Emigration am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts = Zur Kunde Südosteuropas: Albanologische Studien. Vienna: Böhlau-Verlag. p. Bd. 3. ISBN 3-205-99413-2.

- ^ Lazaridis, Gabriella, and Iordanis Psimmenos. "Migrant flows from Albania to Greece: economic, social and spatial exclusion." In Eldorado or Fortress? Migration in Southern Europe, pp. 170-185. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2000.

- ^ Trudgill (2000: 255).

- ^ Botsi (2003: 90); Lawrence (2007: 22; 156)

- ^ Greek Helsinki Monitor - The Arvanites Archived 2016-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laurie Kain Hart. Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece. Archived 2014-11-12 at the Wayback Machine American Ethnologist, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Feb., 1999), pp. 196-220. (article consists of 25 pages). Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association "There are also long standing... unquestioned identification with the Greek nation."

- ^ Euromosaic project (2006). "L'arvanite/albanais en Grèce" (in French). Brussels: European Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Korhonen, Jani; Makartsev, Maxim; Petrusevka, Milica; Spasov, Ljudmil (2016). "Ethnic and linguistic minorities in the border region of Albania, Greece, and Macedonia: An overview of legal and societal status" (PDF). Slavica Helsingiensia. 49: 28.

In several Albanian villages in Epirus (e.g., Plikati in the Ioannina district), the people of Albanian origin are sometimes called Arvanites, although there is an essential difference between them and the Arvanites of central and southern Greece. The Arvanitika-speaking villages form language island(s), as they are not connected geographically to the main Albanian-speaking area, whereas the villages in Epirus border Albanian-speaking territory and thus share more linguistic traits of the type that emerged later in the more extensive Tosk-inhabited territory.

- ^ Xhufi, Pëllumb (February 2006). "Çamët ortodoks". Studime Historike (in Albanian). Albanian Academy of Sciences. 38 (2).

- ^ Vakalopoulos, Kōnstantinos Apostolou (2003). Historia tēs Ēpeirou: apo tis arches tēs Othōmanokratias hōs tis meres mas [History of Epirus: From Ottoman Rule to Present (in Greek). Hērodotos. p. 547. ISBN 9607290976.

Στον καζά των Ιωαννίνων που συγκροτούνταν από 225 χωριά, δεν ζούσε καμιά αλβανική οικογένεια εκτός από κάποιους Αλβανούς υπαλλήλους .

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G.; Gordon Jr., Raymond G.; Grimes, Barbara F. (2005) (in English), Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15 ed.), Dallas, Texas, United States of America: Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) International, p. 789, ISBN 1-55671-159-X, http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=als, retrieved on 2009-03-31

- ^ Greek Helsinki Monitor (1995): "Report: The Arvanites".

- ^ a b Euromosaic (1996): "L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce". Report published by the Institut de Sociolingüística Catalana.

- ^ Mediterranean Migration Observatory - Tables Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Martin, Philip L.; Martin, Susan Forbes; Weil, Patrick (28 March 2018). Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739113417 – via Google Books.

- ^ Κonsta, Anna-Maria; Lazaridis, Gabriella (2010). "Civic Stratification, 'Plastic' Citizenship and 'Plastic Subjectivities' in Greek Immigration Policy". Journal of International Migration and Integration / Revue de l'integration et de la migration internationale. 11 (4): 365. doi:10.1007/s12134-010-0150-8. S2CID 143473178.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Labrianidis, Lois, and Antigone Lyberaki. "Back and forth and in between: returning Albanian migrants from Greece and Italy." Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l'integration et de la migration internationale 5, no. 1 (2004): 77-106.

- ^ Armand Feka (2013-07-16). "Griechenlands verborgene Albaner". Wiener Zeitung. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

Er lächelt und antwortet in einwandfreiem Griechisch: ‚Ich bin eigentlich auch ein Albaner.'

- ^ Lars Brügger; Karl Kaser; Robert Pichler; Stephanie Schwander-Sievers (2002). Umstrittene Identitäten. Grenzüberschreitungen zuhause und in der Fremde. Die weite Welt und das Dorf. Albanische Emigration am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts = Zur Kunde Südosteuropas: Albanologische Studien. Vienna: Böhlau-Verlag. p. Bd. 3. ISBN 3-205-99413-2.

Bibliography[]

- Sansaridou-Hendrickx, Thekla (2017). "The Albanians in the Chronicle(s) of Ioannina: An Anthropological Approach". Acta Patristica et Byzantina. 21 (2): 287–306. doi:10.1080/10226486.2010.11879131. S2CID 163742869.

- Greek people of Albanian descent

- Albanian emigrants to Greece