Culture of Greece

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Greece |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Sport |

|

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultures and states such as the Frankish states, the Ottoman Empire, the Venetian Republic and Bavarian and Danish monarchies have also left their influence on modern Greek culture, but historians credit the Greek War of Independence with revitalising Greece and giving birth to a single entity of its multi-faceted culture.

Greece is widely considered to be the cradle of Western culture[1] and democracy. Modern democracies owe a debt to Greek beliefs in government by the people, trial by jury, and equality under the law. The ancient Greeks pioneered in many fields that rely on systematic thought, including biology, geometry, history,[2] philosophy, and physics. They introduced such important literary forms as epic and lyric poetry, history, tragedy, and comedy. In their pursuit of order and proportion, the Greeks created an ideal of beauty that strongly influenced Western art.[3]

Arts[]

Architecture[]

Ancient Greece[]

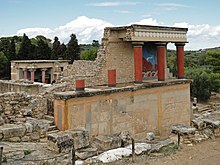

The first great ancient Greek civilisation was the Minoan one, a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, flourishing from c. 3000 BC to c. 1450 BC and, after a late period of decline, finally ending around 1100 BC, during the early Greek Dark Ages. They built city houses and royal palaces. At Knossos, the palace of king Minos, composed of two and three levels, had over 500 rooms and mant terraces with porticos and stairs. The interior of this palace included monumental reception halls, vast apartment for the queen and bridesmaids, baths with complete sewage and drain systems, food deposits, shops, theatres, sport arenas, and other things. The walls are made of polished marble or masonry covered with highly-decorated frescos. Besides the place, on the island of Santorini, an entire Minoan city was discovered in 1967, called Akrotiri.[4] Later, the Mycenaean civilization erected palatial structures at Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos.

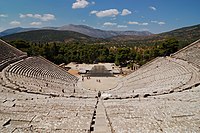

After the Greek Dark Ages, architecture became what we know today. Without a doubt, ancient Greek Classical architecture, together with Roman, is one of the most influential styles of all time. Five of the Wonders of the World were Greek: the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. However, Ancient Greek architecture is best known from its temples, many of which are found throughout the region, and the Parthenon is a prime example of this, mostly as ruins but many substantially intact. Later, they will serve as inspiration for Neoclassical architects during the late 18th and the 19th century. The most well-known temples are the Parthenon and the Erechtheion, both on the Acropolis of Athens. Another type of important Ancient Greek buildings were the theatres. Both temples and theatres used a complex mix of optical illusions and balanced ratios.

Classical Ancient Greek temples usually consist of a base with stairs at each edges (known as crepidoma), a cella (or naos) with a cult statue in it, columns, an entablature, and two pediments, one on the front side and another in the back. By the 4th century BC, Greek architects and stonemasons had developed a system of rules for all buildings known as the orders: the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian. They are most easily recognised by their columns (especially by the capitals). The Doric column is stout and basic, the Ionic one is slimmer and has four scolls (called volutes) at the corners of the capital, and the Corinthian column is just like the Ionic one, but the capital is completely different, being decorated with acanthus leafs and four scrolls.[5]

Byzantine Greece[]

Byzantine architects have built city walls, palaces, hippodromes, bridges, aqueducts, but most importantly, churches. They left us many types of churches, including the basilica (the most wide-spread type, and the one that reached the greatest development). From basilica derive other two types, the circular one and the octagonal one. Another monumental type of church is the one in shape of an Orthodox cross, and with five domes. In Mainland Greece, the most wide-spread type of church was the cruciform one, with one or more domes. Also, a big number of churches of these shapes exist in Moscow, Novgorod or Kiev, as well as in Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia and Albania. Through modifications and adaptations of local inspiration, the Byzantine style will be used as the main source of inspiration for architectural styles in Eastern Orthodox countries.[6] For example, in Romania, the Brâncovenesc style is highly based on Byzantine architecture, but also has individual Romanian characteristics.

Just like how the Parthenon is the most famous monument of the Ancient Greek religion, Hagia Sophia remained an iconic church of Christianity. The temples of both religions differ substantially in terms of their exterior and interior aspect. In Antiquity, the exterior was the most important part of the temple, because in the interior, where the cult statue of the deity to whom the temple was built was kept, only the priest had access. The ceremonies here held outside, and what the worshipers view was the facade of the temple, consisting of columns, with an entablature and two pediments. Meanwhile, Christian liturgies were held in the interior of the churches, the exterior usually having little to no ornamentation.[7]

Byzantine architecture often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds.[8] The building material used by Byzantine architects was no longer marble, which was very appreciated by the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows.[9]

Modern Greece[]

After the independence of Greece and during the nineteenth century, the Neoclassical architecture was heavily used for both public and private building.[10] The 19th-century architecture of Athens and other cities of the Greek Kingdom is mostly influenced by the Neoclassical architecture, with architects like Theophil Hansen, Ernst Ziller, Panagis Kalkos, Lysandros Kaftanzoglou, Anastasios Metaxas and Stamatios Kleanthis. Regarding the churches, Greece also experienced the Neo-Byzantine revival.

In 1933 the Athens Charter, a manifesto of the modernist movement, was signed and was published later by Le Corbusier. Architects of this movement were among others: the Bauhaus-architect Ioannis Despotopoulos, Dimitris Pikionis, Patroklos Karantinos and Takis Zenetos. After World War II and the Greek civil war, the massive construction of condominiums in the major Greek city centres, was a major contributory factor for the Greek economy and the post-war recovery. The first skyscrapers were also constructed during the 1960s and 1970s, such as the OTE Tower and the Athens Tower Complex.

Cinema[]

Cinema first appeared in Greece in 1896 but the first actual cine-theatre was opened in 1907. In 1914 the Asty Films Company was founded and the production of long films begun. Golfo (Γκόλφω), a well known traditional love story, is the first Greek long movie, although there were several minor productions such as newscasts before this. In 1931, Orestis Laskos directed Daphnis and Chloe (Δάφνις και Χλόη), contained the first nude scene in the history of European cinema; it was also the first Greek movie which was played abroad. In 1944 Katina Paxinou was honoured with the Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for For Whom the Bell Tolls.

The 1950s and early 1960s are considered by many as the Golden age of Greek cinema. Directors and actors of this era were recognized as important historical figures in Greece and some gained international acclaim: Mihalis Kakogiannis, Alekos Sakellarios, Melina Mercouri, Nikos Tsiforos, Iakovos Kambanelis, Katina Paxinou, Nikos Koundouros, Ellie Lambeti, Irene Papas, etc. More than sixty films per year were made, with the majority having film noir elements. Notable films were The Counterfeit Coin (Η κάλπικη λίρα, 1955, directed by Giorgos Tzavellas), Bitter Bread (Πικρό Ψωμί, 1951, directed by Grigoris Grigoriou), The Ogre of Athens (O Drakos, 1956, directed by Nikos Koundouros), Stella (1955, directed by Cacoyannis and written by Kampanellis). Cacoyannis also directed Zorba the Greek with Anthony Quinn which received Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Film nominations. Finos Film also contributed to this period with movies such as Λατέρνα, Φτώχεια και Φιλότιμο, The Auntie from Chicago (Η Θεία από το Σικάγο), Maiden's Cheek (Το ξύλο βγήκε από τον Παράδεισο), and many more. During the 1970s and 1980s Theo Angelopoulos directed a series of notable and appreciated movies. His film Eternity and a Day won the Palme d'Or and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival.

There were also internationally renowned filmmakers in the Greek diaspora such as the Greek-American Elia Kazan.

Music and dances[]

Greece has a diverse and highly influential musical tradition, with ancient music influencing the Roman Empire, and Byzantine liturgical chants and secular music influencing and the Renaissance. Modern Greek music combines these elements, to carry Greeks' interpretation of a wide range of musical forms.

Ancient Greece[]

The history of music in Greece begins with the music of ancient Greece, largely structured on the Lyre and other supporting string instruments of the era. Beyond the well-known structural legacies of the Pythagorean scale, and the related mathematical developments it upheld to define western classical music, relatively little is understood about the precise character of music during this period; we do know, however, that it left, as so often, a strong mark on the culture of Rome. What has been gleaned about the social role and character of ancient Greek music comes largely from pottery and other forms of Greek art.

Ancient Greeks believed that dancing was invented by the gods and therefore associated it with religious ceremony. They believed that the gods offered this gift to select mortals only, who in turn taught dancing to their fellow-men.

Periodic evidence in ancient texts indicates that dance was held in high regard, in particular for its educational qualities. Dance, along with writing, music, and physical exercise, was fundamental to the commenced in a circle and ended with the dancers facing one another. When not dancing in a circle the dancers held their hands high or waved them to the left and right. They held cymbals (very like the zilia of today) or a kerchief in their hands, and their movements were emphasized by their long sleeves. As they danced, they sang, either set songs or extemporized ones, sometimes in unison, sometimes in refrain, repeating the verse sung by the lead dancer. The onlookers joined in, clapping the rhythm or singing. Professional singers, often the musicians themselves, composed lyrics to suit the occasion.

Byzantine Greece[]

The Byzantine music is also of major significance to the history and development of European music, as liturgical chants became the foundation and stepping stone for music of the Renaissance (see: Renaissance Music). It is also certain that Byzantine music included an extensive tradition of instrumental court music and dance; any other picture would be both incongruous with the historically and archaeologically documented opulence of the Eastern Roman Empire. There survive a few but explicit accounts of secular music. A characteristic example is the accounts of pneumatic organs, whose construction was further advanced in the eastern empire prior to their development in the west following the Renaissance.

Byzantine instruments included the guitar, single, double or multiple flute, sistrum, timpani (drum), psaltirio, Sirigs, lyre, cymbals, keras and kanonaki.

Popular dances of this period included the Syrtos, Geranos, Mantilia, Saximos, Pyrichios, and Kordakas . Some of these dances have their origins in the ancient period and are still enacted in some form today.

Modern Greece[]

A range of domestically and internationally known composers and performers across the musical spectrum have found success in modern Greece, while traditional Greek music is noted as a mixture of influences from indigenous culture with those of west and east. A few Ottoman as well as medieval Italian elements can be heard in the traditional songs, dhimotiká, as well as in the modern bluesy rembétika music. A well-known Greek musical instrument is the bouzouki. "Bouzouki" is a descriptive Turkish name, but the instrument itself is probably of Greek origin (from the ancient Greek lute known as pandoura, a kind of guitar, clearly visible in ancient statues, especially female figurines of the "Tanagraies" playing cord instruments).

Famous Greek musicians and composers of modern era include the central figure of 20th-century European modernism Iannis Xenakis, a composer, architect and theorist. Maria Callas, Nikos Skalkottas, Mikis Theodorakis, Dimitris Mitropoulos, Manos Hadjidakis and Vangelis also lead twentieth-century Greek contributions, alongside Demis Roussos, Nana Mouskouri, Yanni, Georges Moustaki, Eleni Karaindrou and others.

The birth of the first School of modern Greek classical music (Heptanesean or Ionian School, Greek:Επτανησιακή Σχολή) came through the Ionian Islands (notable composers include Spyridon Samaras, Nikolaos Mantzaros and Pavlos Carrer), while Manolis Kalomiris is considered the founder of the Greek National School.

Greece is one of the few places in Europe where the day-to-day role of folk dance is sustained. Rather than functioning as a museum piece preserved only for performances and special events, it is a vivid expression of everyday life. Occasions for dance are usually weddings, family celebrations, and paneyeria (Patron Saints' name days). Dance has its place in ceremonial customs that are still preserved in Greek villages, such as dancing the bride during a wedding and dancing the trousseau of the bride during the wedding preparations. The carnival and Easter offer more opportunities for family gatherings and dancing. Greek taverns providing live entertainment often include folk dances in their program.

Regional characteristics have developed over the years because of variances in climatic conditions, land morphology and people's social lives. Kalamatianos and Syrtos are considered Pan-Hellenic dances and are danced all over the world in diaspora communities. Others have also crossed boundaries and are known beyond the regions where they originated; these include the Pentozali from Crete, Hasapiko from Constantinople, Zonaradikos from Thrace, Serra from Pontos and Balos from the Aegean islands.

The avant-garde choreographer, director and dancer Dimitris Papaioannou was responsible for the critically successful opening ceremony of the 2004 Olympic Games, with a conception that reflected the classical influences on modern and experimental Greek dance forms.

Painting[]

Ancient Greece[]

There were several interconnected traditions of painting in ancient Greece. Due to their technical differences, they underwent somewhat differentiated developments. Not all painting techniques are equally well represented in the archaeological record. The most respected form of art, according to authors like Pliny or Pausanias, were individual, mobile paintings on wooden boards, technically described as panel paintings. Also, the tradition of wall painting in Greece goes back at least to the Minoan and Mycenaean Bronze Age, with the lavish fresco decoration of sites like Knossos, Tiryns and Mycenae.

Much of the figural or architectural sculpture of ancient Greece was painted colourfully. This aspect of Greek stonework is described as polychrome (from Greek πολυχρωμία, πολύ = many and χρώμα = colour). Due to intensive weathering, polychromy on sculpture and architecture has substantially or totally faded in most cases.

Byzantine Greece[]

Byzantine art is the term created for the Eastern Roman Empire from about the 5th century AD until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The most salient feature of this new aesthetic was its "abstract," or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The Byzantine painting concentrated mainly on icons and hagiographies.

Post-Byzantine and Modern Greece[]

The term Cretan School describes an important school of icon painting, also known as Post-Byzantine art, which flourished while Crete was under Venetian rule during the late Middle Ages, reaching its climax after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the central force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. The Cretan artists developed a particular style of painting under the influence of both Eastern and Western artistic traditions and movements. The most famous product of the school, El Greco, was the most successful of the many artists who tried to build a career in Western Europe.

The Heptanese School of painting succeeded the Cretan school as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence, and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The school was based in the Ionian islands, which were not part of Ottoman Greece, from the middle of the 17th century until the middle of the 19th century.

Modern Greek painting, after the independence and the creation of the modern Greek state, began to be developed around the time of Romanticism and the Greek artists absorbed many elements from their European colleagues, resulting in the culmination of the distinctive style of Greek Romantic art. Notable painters of the era include Nikolaos Gyzis, Georgios Jakobides, Nikiphoros Lytras, Konstantinos Volanakis and Theodoros Vryzakis.

Sculpture[]

Ancient Greece[]

Ancient Greek monumental sculpture was composed almost entirely of marble or bronze; with cast bronze becoming the favoured medium for major works by the early 5th century. Both marble and bronze are fortunately easy to form and very durable. Chryselephantine sculptures, used for temple cult images and luxury works, used gold, most often in leaf form and ivory for all or parts (faces and hands) of the figure, and probably gems and other materials, but were much less common, and only fragments have survived. By the early 19th century, the systematic excavation of ancient Greek sites had brought forth a plethora of sculptures with traces of notably multicolored surfaces. It was not until published findings by German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann in the late 20th and early 21st century that the painting of ancient Greek sculptures became an established fact. Using high-intensity lamps, ultraviolet light, specially designed cameras, plaster casts, and certain powdered minerals, Brinkmann proved that the entire Parthenon, including the actual structure as well as the statues, had been painted.

Byzantine Greece[]

The Byzantines inherited the early Christian distrust of monumental sculpture in religious art, and produced only reliefs, of which very few survivals are anything like life-size, in sharp contrast to the medieval art of the West, where monumental sculpture revived from Carolingian art onwards. Small ivories were also mostly in relief.

The so-called "minor arts" were very important in Byzantine art and luxury items, including ivories carved in relief as formal presentation Consular diptychs or caskets such as the Veroli casket, hardstone carvings, enamels, jewelry, metalwork, and figured silks were produced in large quantities throughout the Byzantine era. Many of these were religious in nature, although a large number of objects with secular or non-representational decoration were produced: for example, ivories representing themes from classical mythology. Byzantine ceramics were relatively crude, as pottery was never used at the tables of the rich, who ate off silver.

Modern Greece[]

After the establishment of the Greek Kingdom and the western influence of Neoclassicism, sculpture was re-discovered by the Greek artists. Main themes included ancient Greek antiquity, the War of Independence and important figures of Greek history.

Notable sculptors of the new state were Leonidas Drosis (his major work was the extensive neo-classical architectural ornament at the Academy of Athens, Lazaros Sochos, , , Ioannis Kossos, Yannoulis Chalepas, Georgios Bonanos and .

Theatre[]

Ancient Greece[]

Theatre was born in Greece. The city-state of Classical Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and military power during this period, was its centre, where it was institutionalised as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy (late 6th century BC), comedy (486 BC), and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres to emerge there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common cultural identity.

The word τραγῳδία (tragoidia), from which the word "tragedy" is derived, is a compound of two Greek words: τράγος (tragos) or "goat" and ᾠδή (ode) meaning "song", from ἀείδειν (aeidein), "to sing".[11] This etymology indicates a link with the practices of the ancient Dionysian cults. It is impossible, however, to know with certainty how these fertility rituals became the basis for tragedy and comedy.[12]

Middle Ages[]

During the Byzantine period, the theatrical art was heavily declined. According to Marios Ploritis, the only form survived was the folk theatre (Mimos and Pantomimos), despite the hostility of the official state.[13] Later, during the Ottoman period, the main theatrical folk art was the Karagiozis. The renaissance which led to the modern Greek theatre, took place in the Venetian Crete. Significant dramatists include Vitsentzos Kornaros and Georgios Chortatzis.

Modern Greece[]

The modern Greek theatre was born after the Greek independence, in the early 19th century, and initially was influenced by the Heptanesean theatre and melodrama, such as the Italian opera. The Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo di Corfù was the first theatre and opera house of modern Greece and the place where the first Greek opera, Spyridon Xyndas' The Parliamentary Candidate (based on an exclusively Greek libretto) was performed. During the late 19th and early 20th century, the Athenian theatre scene was dominated by revues, musical comedies, operettas and nocturnes and notable playwrights included Spyridon Samaras, , Theophrastos Sakellaridis and others.

The National Theatre of Greece was founded in 1880. Notable playwrights of the modern Greek theatre include Alexandros Rizos Rangavis, Gregorios Xenopoulos, Nikos Kazantzakis, Angelos Terzakis, Pantelis Horn, Alekos Sakellarios and Iakovos Kambanelis, while notable actors include Cybele Andrianou, Marika Kotopouli, Aimilios Veakis, Orestis Makris, Katina Paxinou, Manos Katrakis and Dimitris Horn. Significant directors include Dimitris Rontiris, Alexis Minotis and Karolos Koun.

Cuisine[]

Greek cuisine has a long tradition and its flavors change with the season and its geography.[14] Greek cookery, historically a forerunner of Western cuisine, spread its culinary influence – via ancient Rome – throughout Europe and beyond.

Ancient Greek cuisine was characterized by its frugality and was founded on the "Mediterranean triad": wheat, olive oil, and wine, with meat being rarely eaten and fish being more common.[15] It was Archestratos in 320 B.C. who wrote the first cookbook in history. Greece has a culinary tradition of some 4,000 years.[16]

The Byzantine cuisine was similar to the classical cuisine including however new ingredients that were not available before, like caviar, nutmeg and lemons, basil, with fish continuing to be an integral part of the diet. Culinary advice was influenced by the theory of humors, first put forth by the ancient Greek doctor Claudius Aelius Galenus.[17]

The modern Greek cuisine has also influences from the Ottoman and Italian cuisine due to the Ottoman and Venetian dominance through the centuries.

Wine production[]

Greece is one of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world. The earliest evidence of Greek wine has been dated to 6,500 years ago[18][19] where wine was produced on a household or communal basis. In ancient times, as trade in wine became extensive, it was transported from end to end of the Mediterranean; Greek wine had especially high prestige in Italy under the Roman Empire. In the medieval period, wines exported from Crete, Monemvasia and other Greek ports fetched high prices in northern Europe.

Education[]

Education in Greece is compulsory for all children 6–15 years old; namely, it includes Primary (Dimotiko) and Lower Secondary (Gymnasio) Education. The school life of the students, however, can start from the age of 2.5 years (pre-school education) in institutions (private and public) called "Vrefonipiakoi Paidikoi Stathmi" (creches). In some Vrefonipiakoi Stathmoi there are also Nipiaka Tmimata (nursery classes) which operate along with the Nipiagogeia (kindergartens).

Post-compulsory Secondary Education, according to the reforms of 1997 and 2006, consists of two main school types: Genika Lykeia (General Upper Secondary Schools) and the Epaggelmatika Lykeia (Vocational Upper Secondary Schools), as well as the Epaggelmatikes Sxoles (Vocational Schools). Musical, Ecclesiastical and Physical Education Gymnasia and Lykeia are also in operation.

Post-compulsory Secondary Education also includes the Vocational Training Institutes (IEK), which provide formal but unclassified level of education. These Institutes are not classified as an educational level, because they accept both Gymnasio (lower secondary school) and Lykeio (upper secondary school) graduates according to the relevant specializations they provide. Public higher education is divided into Universities and Technological Education Institutes (TEI). Students are admitted to these Institutes according to their performance at national level examinations taking place at the third grade of Lykeio. Additionally, students are admitted to the Hellenic Open University upon the completion of the 22 year of age by drawing lots.

Nea Dimokratia (New Democracy), the Greek conservative right political party, has claimed that it will change the law so that private universities gain recognition. Without official recognition, students who have an EES degree are unable to work in the public sector. PASOK took some action after EU intervention, namely the creation of a special government agency that certifies the vocational status of certain EES degree holders. However, their academic status still remains a problem. The issue of full recognition is still an issue of debate among Greek politicians.

The (iED) is a Greek Non-governmental organization formed for the promotion of innovation and for enhancing the spirit of entrepreneurship intending to link with other European initiatives.

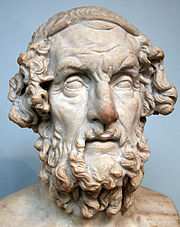

Greek people[]

The origins of Western literature and of the main branches of Western learning may be traced to the era of Greek greatness that began before 700 BC with the epics of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Hesiod, the first didactic poet, put into epic verse his descriptions of pastoral life, including practical advice on farming, and allegorical myths. The poets Alcaeus of Mytilene, Sappho, Anacreon, and Bacchylides wrote of love, war, and death in lyrics of great feeling and beauty. Pindar celebrated the Panhellenic athletic festivals in vivid odes. The fables of the slave Aesop have been famous for more than 2,500 years. Three of the world's greatest dramatists were Aeschylus, author of the Oresteia trilogy; Sophocles, author of the Theban plays; and Euripides, author of Medea, The Trojan Women, and The Bacchae. Aristophanes, the greatest author of comedies, satirized the mores of his day in a series of brilliant plays. Three great historians were Herodotus, regarded as the father of history, known for The Persian Wars; Thucydides, who generally avoided myth and legend and applied greater standards of historical accuracy in his History of the Peloponnesian War; and Xenophon, best known for his account of the Greek retreat from Persia, the Anabasis. Outstanding literary figures of the Hellenistic period were Menander, the chief representative of a newer type of comedy; the poets Callimachus, Theocritus, and Apollonius Rhodius, author of the Argonautica; and Polybius, who wrote a detailed history of the Mediterranean world. Noteworthy in the Roman period were Strabo, a writer on geography; Plutarch, the father of biography, whose Parallel Lives of famous Greeks and Romans is a chief source of information about great figures of antiquity; Pausanias, a travel writer; and Lucian, a satirist.

The leading philosophers of the period preceding Greece's golden age were Thales, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Protagoras, and Democritus. Socrates investigated ethics and politics. His greatest pupil, Plato, used Socrates' question-and-answer method of investigating philosophical problems in his famous dialogues. Plato's pupil Aristotle established the rules of deductive reasoning but also used observation and inductive reasoning, applying himself to the systematic study of almost every form of human endeavor. Outstanding in the Hellenistic period were Epicurus, the philosopher of moderation; Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism; and Diogenes of Sinope, the famous Cynic. The oath of Hippocrates, the father of medicine, is still recited by newly graduating physicians. Euclid evolved the system of geometry that bears his name. Archimedes discovered the principles of mechanics and hydrostatics. Eratosthenes calculated the earth's circumference with remarkable accuracy, and Hipparchus Founded scientific astronomy. Galen was an outstanding physician of ancient times.

The sculptor Phidias created the statue of Athena and the figure of Zeus in the temple at Olympia and supervised the construction and decoration of the Parthenon. Another renowned sculptor was Praxiteles.

The legal reforms of Solon served as the basis of Athenian democracy. The Athenian general Miltiades the Younger led the victory over the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC, and Themistocles was chiefly responsible for the victory at Salamis 10 years later. Pericles, the virtual ruler of Athens for more than 25 years, added to the political power of that city, inaugurated the construction of the Parthenon and other noteworthy buildings, and encouraged the arts of sculpture and painting. With the decline of Athens, first Sparta and then Thebes, under the great military tactician Epaminondas, gained the ascendancy; but soon thereafter, two military geniuses, Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great, gained control over all of Greece and formed a vast empire stretching as far east as India. It was against Philip that Demosthenes, the greatest Greek orator, directed his diatribes, the Philippics.

The most renowned Greek painter during the Renaissance was El Greco, born in Crete, whose major works, painted in Spain, have influenced many 20th-century artists. An outstanding modern literary figure is Nikos Kazantzakis, a novelist and poet who composed a vast sequel to Homer's Odyssey. Leading modern poets are Kostis Palamas, and Constantine P. Cavafy, as well as George Seferis, and Odysseus Elytis, winners of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1963 and 1979, respectively. The work of social theorist Cornelius Castoriadis is known for its multidisciplinary breadth. Musicians of stature are the composers Nikos Skalkottas, Iannis Xenakis, and Mikis Theodorakis; the conductor Dmitri Mitropoulos; and the soprano Maria Callas. Filmmakers who have won international acclaim are Greek-Americans John Cassavetes and Elia Kazan, and Greeks Michael Cacoyannis and Costa-Gavras. Actresses of note are Katina Paxinou; Melina Mercouri, who was appointed minister of culture and science in the Socialist cabinet in 1981; and Irene Papas.

Outstanding Greek public figures in the 20th century include Cretan-born Eleutherios Venizelos, prominent statesman of the interwar period; Ioannis Metaxas, dictator from 1936 until his death; Constantine Karamanlis, prime minister (1955–63, 1974–80) and president (1980–85) of Greece; George Papandreou, head of the Center Union Party and prime minister (1963–65); and his son Andreas Papandreou, the PASOK leader who became prime minister in 1981. Costas Simitis was leader of PASOK and prime minister from 1996 to 2004. He was succeeded by Kostas Karamanlis.

Language[]

The Greek language is the official language of the Hellenic Republic and Republic of Cyprus and has a total of 15 million speakers worldwide; it is an Indo-European language. It is particularly remarkable in the depth of its continuity, beginning with the pre-historic Mycenaean Greek and the Linear B script and maybe the Linear A script associated with Minoan civilization, though Linear A is still undeciphered. Greek language is clearly detected in the Mycenaean language and the Cypriot syllabary, and eventually the dialects of Ancient Greek, of which Attic Greek bears the most resemblance to Modern Greek. The history of the language spans over 3400 years of written records.

Greek has had enormous impact on other languages both directly on the Romance languages, and indirectly through its influence on the emerging Latin language during the early days of Rome. Signs of this influence, and its many developments, can be seen throughout the family of Western European languages.

Internet and "Greeklish"[]

More recently, the rise of internet-based communication services as well as cell phones have caused a distinctive form of Greek written partially, and sometimes fully in Latin characters to emerge; this is known as Greeklish, a form that has spread across the Greek diaspora and even to the two countries with majority Greek population, Greece and Cyprus.

Katharevousa[]

Katharévousa (Καθαρεύουσα) is a form of the Greek Language midway between modern and ancient forms set in train during the early nineteenth century by Greek intellectual and revolutionary leader Adamantios Korais, intended to return the Greek language closer to its ancient form. Its influence, in recent years, evolved toward a more formal role, and it came to be used primarily for official purposes such as diplomacy, politics, and other forms of official documentation. It has nevertheless had significant effects on the Greek language as it is still written and spoken today, and both vocabulary and grammatical and syntactical forms have re-entered Modern Greek via Katharevousa.

Dialects[]

There are a variety of dialects of the Greek language; the most notable include Cappadocian, Cretan Greek (which is closely related to most Aegean Islands' dialects), Cypriot Greek, Pontic Greek, the Griko language spoken in Southern Italy, and Tsakonian, still spoken in the modern prefecture of Arcadia and widely noted as a surviving regional dialect of Doric Greek.

Literature[]

Greece has a remarkably rich and resilient literary tradition, extending over 2800 years and through several eras. The Classical era is that most commonly associated with Greek Literature, beginning in 800 BCE and maintaining its influence through to the beginnings of Byzantine period, whereafter the influence of Christianity began to spawn a new development of the Greek written word. The many elements of a millennia-old tradition are reflected in Modern Greek literature, including the works of the Nobel laureates Odysseus Elytis and George Seferis.

Ancient Greece[]

The first recorded works in the western literary tradition are the epic poems of Homer and Hesiod. Early Greek lyric poetry, as represented by poets such as Sappho and Pindar, was responsible for defining the lyric genre as it is understood today in western literature. Aesop wrote his Fables in the 6th century BC. These innovations were to have a profound influence not only on Roman poets, most notably Virgil in his epic poem on the founding of Rome, The Aeneid, but one that flourished throughout Europe.

Classical Greece is also judged the birthplace of theatre. Aeschylus introduced the ideas of dialogue and interacting characters to playwriting and in doing so, he effectively invented "drama": his Oresteia trilogy of plays is judged his crowning achievement. Other refiners of playwriting were Sophocles and Euripides. Aristophanes, a comic playwright, defined and shaped the idea of comedy as a theatrical form.

Herodotus and Thucydides are often attributed with developing the modern study of history into a field worthy of philosophical, literary, and scientific pursuit. Polybius first introduced into study the concept of military history.

Philosophy entered literature in the dialogues of Plato, while his pupil Aristotle, in his work the Poetics, formulated the first set criteria for literary criticism. Both these literary figures, in the context of the broader contributions of Greek philosophy in the Classical and Hellenistic eras, were to give rise to idea of political Science, the study of political evolution and the critique of governmental systems.

Byzantine Greece[]

The growth of Christianity throughout the Greco-Roman world in the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries, together with the Hellenization of the Byzantine Empire of the period, would lead to the formation of a unique literary form, combining Christian, Greek and Oriental influences. In its turn, this would promote developments such as Cretan poetry, the growth of poetic satire in the Greek East and the several pre-eminent historians of the period.

Modern Greece[]

Modern Greek literature refers to literature written in the Greek language from the 11th century, with texts written in a language that is more familiar to the ears of Greeks today than is the language of the early Byzantine times.

The Cretan Renaissance poem Erotokritos is undoubtedly the masterpiece of this early period of modern Greek literature, and represents one of its supreme achievements. It is a verse romance written around 1600 by Vitsentzos Kornaros (1553–1613). The other major representative of the Cretan literature was Georgios Chortatzis and his most notable work was Erofili. Other plays include The Sacrifice of Abraham by Kornaros, Panoria and Katsourbos by Chortatzis, by , Stathis (comedy) and Voskopoula by unknown artists.

Much later, Diafotismos was an ideological, philological, linguistic and philosophical movement among 18th century Greeks that translate the ideas and values of European Enlightenment into the Greek world. Adamantios Korais and Rigas Feraios are two of the most notable figures. In 1819, , written by , was a lampoon against the Greek intellectual Adamantios Korais and his linguistic views, who favoured the use of a more conservative form of the Greek language, closer to the ancient.

The years before the Greek Independence, the Ionian islands became the center of the Heptanese School (literature). Its main characteristics was the Italian influence, romanticism, nationalism and use of Demotic Greek. Notable representatives were Andreas Laskaratos, Andreas Kalvos, Aristotelis Valaoritis and Dionysios Solomos.

After the independence the intellectual center was transferred in Athens. A major figure of this new era was Kostis Palamas, considered "national poet" of Greece. He was the central figure of the Greek literary generation of the 1880s and one of the cofounders of the so-called New Athenian School (or Palamian School). Its main characteristic was the use of Demotic Greek. He was also the writer of the Olympic Hymn.

Moving into the twentieth century, the modern Greek literary tradition spans the work of Constantine P. Cavafy, considered a key figure of twentieth-century poetry, Giorgos Seferis (whose works and poems aimed to fuse the literature of Ancient and Modern Greece) and Odysseas Elytis, both of whom won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Nikos Kazantzakis is also considered a dominant figure, with works such as The Last Temptation of Christ and The Greek Passion receiving international recognition.

Philosophy, science and mathematics[]

The Greek world is widely regarded as having given birth to scientific thought by means of observation, thought, and development of a theory without the intervention of a supernatural force. Thales, Anaximander and Democritus were amongst those contributing significantly to the establishment of this tradition. It is also, and perhaps more commonly in the western imagination, identified with the dawn of Western philosophy, as well as a mapping out of the natural sciences. Greek developments of mathematics continued well up until the decline of the Byzantine Empire. In the modern era Greeks continue to contribute to the fields of science, mathematics and philosophy.

Ancient Greece[]

The tradition of philosophy in ancient Greece accompanied its literary development. Greek learning had a profound influence on Western and Middle Eastern civilizations. The works of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek philosophers profoundly influenced Classical thought, the Islamic Golden Age, and the Renaissance.

The Ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians were very good at maths and at building geometric tombs, but they're not famous for philosophy. Their religious explanations of things are elaborate but unconvincing in philosophical terms. Theocratic societies governed by priestly castes are usually static and monopolise thought. They insist on orthodox explanations and actively discourage independent and unconventional ideas. The Ancient Greeks invented philosophy, but no-one really knows why. Because of their trade across the Mediterranean Sea, they borrowed myths and mysticism as well as architecture and mathematics from their neighbouring civilisations. Some Greek thinkers decided to not accept religious explanations for how the world works, an example being Xenophanes. They just thought that there just had to be some king of underlying order or logic for the way things are. This will later be given to Ancient Rome and Modern civilisation.[20]

In medicine, doctors still refer to the Hippocratic oath, instituted by Hippocrates, regarded as foremost in laying the foundations of medicine as a science. Galen built on Hippocrates' theory of the four humours, and his writings became the foundation of medicine in Europe and the Middle East for centuries. The physicians Herophilos and Paulus Aegineta were pioneers in the study of anatomy, while Pedanius Dioscorides wrote an extensive treatise on the practice of pharmacology.

The period of Classical Greece (from 800 BC until the rise of Macedon, a Greek state in the north) is that most often associated with Greek advances in science. Thales of Miletus is regarded by many as the father of science; he was the first of the ancient philosophers to seek to explain the physical world in terms of natural rather than supernatural causes. Pythagoras was a mathematician often described as the "father of numbers"; it is believed that he had the pioneering insight into the numerical ratios that determine the musical scale, and the Pythagorean theorem is commonly attributed to him. Diophantus of Alexandria, in turn, was the "father of algebra". Many parts of modern geometry are based on the work of Euclid, while Eratosthenes was one of the first scientific geographers, calculating the circumference of the earth and conceiving the first maps based on scientific principles.

The Hellenistic period, following Alexander's conquests, continued and built upon this knowledge. Hipparchus is considered the pre-eminent astronomical observer of the ancient world, and was probably the first to develop an accurate method for the prediction of solar eclipse, while Aristarchus of Samos was the first known astronomer to propose a heliocentric model of the solar system, though the geocentric model of Ptolemy was more commonly accepted until the seventeenth century. Ptolemy also contributed substantially to cartography and to the science of optics. For his part Archimedes was the first to calculate the value of π and a geometric series, and also the earliest known mathematical physicist discovering the law of buoyancy, as well as conceiving the irrigation device known as Archimedes' screw.

Byzantine Greece[]

The Byzantine period remained largely a period of preservation in terms of classical Greco-Roman texts; there were, however, significant advances made in the fields of medicine and historical scholarship. Theological philosophy also remained an area of study, and there was, while not matching the achievements of preceding ages, a certain increase in the professionalism of study of these subjects, epitomized by the founding of the University of Constantinople.

Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, the architects of the famous Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, also contributed towards mathematical theories concerning architectural form, and the perceived mathematical harmony needed to create a multi-domed structure. These ideas were to prove a heavy influence on the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan in his creation of the Blue Mosque, also in Constantinople. Tralles in particular produced several treatises on the Natural Sciences, as well as his other forays into mathematics such as Conic Sections.

The gradual migration of Greeks from Byzantium to the Italian city states following the decline of the Byzantine Empire, and the texts they brought with them combined with the academic positions they held[specify], was a major factor in lighting the first sparks of the Italian Renaissance.[citation needed]

Modern Greece[]

Greeks continue to contribute to science and technology in the modern world. John Argyris, a mathematician and engineer, was among the creators of the finite element method and the direct stiffness method. Constantin Carathéodory made significant contributions to the theory of functions of a real variable, calculus of variations and measure theory, credited with the introduction of several mathematical theorems. In physics, John Iliopoulos is known for the prediction of the charm quark and the proposition of the GIM mechanism, as well as the Fayet–Iliopoulos D-term formula, while Dimitri Nanopoulos is one of the principal developers of the Flipped SU(5) model.

Biologist Fotis Kafatos pioneers in the field of molecular cloning and genomics, and he was the founding president of the European Research Council. In medicine, Georgios Papanikolaou contributed heavily to the development of cervical screening inventing the Pap test, which is among the most common methods of cervical screening worldwide.

Car designer Alec Issigonis designed the groundbreaking and iconic Mini automobile, while Michael Dertouzos was amongst the pioneers of the Internet, instrumental in defining the World Wide Web Consortium and director for 27 years of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, which innovated in a variety of areas during his term. Nicholas Negroponte, is the founder of the MIT Media Lab and the One Laptop per Child project aiming to extend Internet access in the developing world. Joseph Sifakis, a computer scientist, has won a Turing Award for his pioneering work on model checking.

Politics[]

Greece is a Parliamentary Republic with a president assuming a more ceremonial role than in some other republics, and the Prime Minister chosen from the leader of the majority party in the parliament. Greece has a codified constitution and a written Bill of Rights embedded within it. The current Prime Minister is Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

The politics of the third Hellenic Republic have been dominated by two main political parties, the self-proclaimed socialists of PASOK and the conservative New Democracy. Until recently[when?] PASOK had dominated the political scene, presiding over favourable growth rates economically but in the eyes of critics failing to deliver where unemployment and structural issues such as market liberalization were concerned.

New Democracy's election to government in 2004 has led to various initiatives to modernize the country, such as the education university scheme above as well as labour market liberalization. Politically there has been massive opposition to some of these moves owing to a large, well organized workers' movement in Greece, which distrusts the right wing administration and neo-liberal ideas. The population in general appears to accept many of the initiatives, reflected in governmental support; on the economic front many are so far warming to the reforms made by the administration, which have been largely rewarded with above average Eurozone growth rates. New Democracy were re-elected in September 2007.

A number of other smaller political parties exist. They include the third largest party (the Communist Party), which still commands large support from many rural working areas as well as some of the immigrant population in Greece, as well as the far-right Popular Orthodox Rally, with the latter, while commanding a mere three and a half per cent of votes, seeking to capitalise on opposition in some quarters regarding Turkey's EU accession and any tension in the Aegean. There is also a relatively small, but well organized anarchist movement, though its status in Greece has been somewhat exaggerated by media overseas.

The political process is energetically and openly participated in by the people of Greece, while public demonstrations are a continual feature of Athenian life; however, there have been criticisms of a governmental failure to sufficiently involve minorities in political debate and hence a sidelining of their opinions. In general, politics is regarded as an acceptable subject to broach on almost every social occasion, and Greeks are often very vocal about their support (or lack of it) for certain policy proposals, or political parties themselves – this is perhaps reflected in what many consider the rather sensationalist media on both sides of the political spectrum; although this is a feature of most European tabloids.

Public holidays and festivals[]

According to Greek Law every Sunday of the year is a public holiday. In addition, there are four obligatory, official public holidays: March 25 (Greek Independence Day), Easter Monday, August 15 (Assumption or Dormition of the Holy Virgin) and December 25 (Christmas). Two more days, May 1 (Labour Day) and October 28 (Ohi Day), are regulated by law as optional but it is customary for employees to be given the day off. There are, however, more public holidays celebrated in Greece than are announced by the Ministry of Labour each year as either obligatory or optional. The list of these non-fixed National Holidays rarely changes and has not changed in recent decades, giving a total of eleven National Holidays each year.

In addition to the National Holidays, there Public Holidays that are not celebrated nationwide, but only by a specific professional group or a local community. For example, many municipalities have a "Patron Saint", also called "Name Day", or a "Liberation Day", and at this day is customary for schools to have a day off.

Notable festivals include Patras Carnival, Athens Festival and various local wine festivals. The city of Thessaloniki is also home of a number of festivals and events. The Thessaloniki International Film Festival is one of the most important film festivals in Southern Europe,[21]

Religion[]

Ancient Greece[]

Classical Athens may be suggested to have heralded some of the same religious ideas that would later be promoted by Christianity, such as Aristotle's invocation of a perfect God, and Heraclitus' Logos. Plato considered there were rewards for the virtuous in the heavens and punishment for the wicked under the earth; the soul was valued more highly than the material body, and the material world was understood to be imperfect and not fully real (illustrated in Socrates's allegory of the cave).

Hellenistic Greece[]

Alexander's conquests spread classical concepts about the divine, the afterlife, and much else across the eastern Mediterranean area. Jews and early Christians alike adopted the name "hades" when writing about "sheol" in Greek. Greco-Buddhism was the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed in the Indo-Greek Kingdoms. By the advent of Christianity, the four original patriarchates beyond Rome used Greek as their church language.

Byzantine and Modern Greece[]

The Greek Orthodox Church, largely because of the importance of Byzantium in Greek history, as well as its role in the revolution, is a major institution in modern Greece. Its roles in society and larger role in overarching Greek culture are very important; a number of Greeks attend Church at least once a month or more and the Orthodox Easter holiday holds special significance.

The Church of Greece also retains limited political influence through the fact the Greek constitution does not have an explicit separation of Church and State; a debate suggested by more conservative elements of the church in the early 2000s about identification cards and whether religious affiliation might be added to them highlights the friction between state and church on some issues; the proposal unsurprisingly was not accepted. A widely publicised set of corruption scandals in 2004 implicating a small group of senior churchmen also increased national debate on introducing a greater transparency to the church-state relationship.

Greek Orthodox Churches dot both the villages and towns of Greece and come in a variety of architectural forms, from older Byzantine churches, to more modern white brick churches, to newer cathedral-like structures with evident Byzantine influence. Greece (as well as Cyprus), also polled as, ostensibly, one of the most religious countries in Europe, according to Eurostat; however, while the church has wide respect as a moral and cultural institution, a contrast in religious belief with Protestant northern Europe is more obvious than one with Catholic Mediterranean Europe.

Greece also has a significant minority of Muslims in Western Thrace (numbering around 100–150,000), with their places of worship guaranteed since the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. The Greek state has fully approved the construction a main mosque for the more recent Muslim community of Athens under the freedom of religion provisions of the Greek constitution.

Other religious communities living in Greece include Roman Catholics, , Protestants, Armenians, followers of the ancient Greek religion (see Hellenism), Jews and others.

Sports[]

Greece has risen to prominence in a number of sporting areas in recent decades. Football in particular has seen a rapid transformation, with the Greek national football team winning the 2004 UEFA European Football Championship. Many Greek athletes have also achieved significant success and have won world and olympic titles in numerous sports during the years, such as basketball, wrestling, water polo, athletics, weightlifting, with many of them becoming international stars inside their sports. The successful organisation of the Athens 2004 Olympic and Paralympic Games led also to the further development of many sports and has led to the creation of many World class sport venues all over Greece and especially in Athens and Thessaloniki. Greek athletes have won a total 146 medals for Greece in 15 different Olympic sports at the Summer Olympic Games, including the Intercalated Games, an achievement which makes Greece one of the top nations globally, in the world's rankings of medals per capita.

Symbols[]

The national colours of Greece are blue and white. The coat of arms of Greece consists of a white cross on a blue escutcheon which is surrounded by two laurel branches.[22] The Flag of Greece is also blue and white, as defined by Law 851/1978 Regarding the National Flag.[23] It specifies the colour of "cyan" (Greek: κυανό, kyano), meaning "blue", so the shade of blue is ambiguous.

The Order of the Redeemer and military decoration Cross of Valour both have ribbons in the national colours.[24]

Since it was first established, the national emblem has undergone many changes in shape and in design. The original Greek national emblem depicted the goddess Athena and an owl. At the time of Ioannis Kapodistrias, the phoenix, the symbol of rebirth, was added.

Other recognizable symbols include the (throughout the Byzantine Empire) double-headed eagle and the Vergina Sun.

See also[]

- Art in modern Greece

- Hellenistic period

- Hellenic Foundation for Culture

- Center for the Greek Language

- Cinema of Cyprus

- List of Greek films

- List of universities in Greece

- Greek Orthodox Church

- Syncretism in Ancient Greece

- Paideia

- Gaida

- Hellenization

References[]

- ^ Mazlish, Bruce. Civilization And Its Contents. Stanford University Press, 2004. p. 3. Web. 25 Jun. 2012.

- ^ Myres, John. Herodotus, Father of History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953. Web. 25 Jun. 2012.

- ^ Peter Krentz, Ph.D., W. R. Grey Professor of History, Davidson College.

"Greece, Ancient." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2012. Web. 8 July 2012. - ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 35.

- ^ Hodge, Susie (2019). The Short Story of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-7862-7370-3.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 89 & 90.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 92.

- ^ Hodge, Susie (2019). The Short Story of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-7862-7370-3.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 93.

- ^ Manos G. Birēs, Marō Kardamitsē-Adamē, Neoclassical architecture in Greece

- ^ "Definition of TRAGEDY". m-w.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ William Ridgeway, Origin of Tragedy with Special Reference to the Greek Tragedians, p. 83

- ^ "24 γράμματα / Πολυχώρος Πολιτισμού στο Χαλάνδρι (Θέατρο – Μουσική – Γκαλερί- Βιβλίο) » Τo Θέατρο στο Βυζάντιο και την Οθωμανική περίοδο". www.24grammata.com. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Spices and Seasonings:A Food Technology Handbook – Donna R. Tainter, Anthony T. Grenis, p. 223

- ^ Renfrew, Colin (1972). The Emergence of Civilization; The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium B.C. Taylor & Francis. p. 280.

- ^ http://www.focusmm.com/greece/gr_coumn.htm – Archived 2017-07-26 at the Wayback Machine Historical reference about Ancient Greek cuisine.

- ^ Civitello, Linda (2007). Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People. New York: Wiley. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-471-74172-5.

- ^ Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece Archived 2008-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Discovery News.

- ^ Mashed grapes find re-write history of wine Zeenews

- ^ Dave Robinson, Judy Groves (2007). PHILOSOPHY A Graphic Guide. Icon Books Ldt. p. 6, 7. ISBN 978-184056-858-3 Check

|isbn=value: checksum (help). - ^ Thessaloniki International Film Festival – Profile Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine (in Greek)

- ^ Εφημερίς της Κυβερνήσεως 1975, p. Article 2.

- ^ Law 851/1978, p. Article 1, Clause 1.

- ^ Presidency of the Hellenic Republic: The Order of the Redeemer.

Further reading[]

- Bruce Thornton, Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization, Encounter Books, 2002

- Hart, Laurie Kain (1999). "Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece". American Ethnologist. 26 (1): 196–220. doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.1.196. ISSN 0094-0496.

- Simon Goldhill, Who Needs Greek?: Contests in the Cultural History of Hellenism, Cambridge University Press, 2002

- Victor Davis Hanson, John Heath, Who Killed Homer: The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom, Encounter Books, 2001

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Greece. |

- Hellenism Network - Greek Culture

- Sketch of the History of Greek Literature from the Earliest Times to the Reign of Alexander the Great by William Smith

- Anagnosis Books Modern Greek Culture Pages

- The Impact of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism from the Hellenistic Period through the Middle Ages c. 330 BCE- 1250 CE

- The Greek diet and its relationship to health

- Greece a cultural profile

- Greek culture

- Indo-European culture