Albanians in Montenegro

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 30,439 Ethnic Albanians 4.91% of Montenegro population (2011)[1] 32,671 Albanian speakers 5.27% of Montenegro population (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Montenegro | |

| Ulcinj Municipality | 14,076 |

| Tuzi Municipality | 7.786 |

| Bar Municipality | 2,515 |

| Podgorica Municipality | 1.752 |

| Gusinje Municipality | 1,642 |

| Rožaje Municipality | 1,158 |

| Plav Municipality | 833 |

| Other municipalities | 677 |

| Languages | |

| Albanian, Montenegrin | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam majority Roman Catholic minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians, Arbëreshë, Arbanasi, Arvanites, Souliotes | |

Albanians in Montenegro (Albanian: Shqiptarët e Malit të Zi; Montenegrin: Crnogorski Albanci) are an ethnic group in Montenegro of Albanian descent, which constitute 4.91% of Montenegro's total population.[2] They are the largest non-Slavic ethnic group in Montenegro.

Albanians are particularly concentrated in southeastern and eastern Montenegro alongside the border with Albania in the following municipalities including Ulcinj (71% of total population), Tuzi (68%), Gusinje (40%), Plav (19%), Bar (6%), Podgorica (5%) and Rožaje (5%).[3][4]

The largest Albanian town in Montenegro is Ulcinj, where the headquarters of the Albanian National Council are located.

Geography[]

Albanians in Montenegro are concentrated along the Albania-Montenegro border in areas that were incorporated in Montenegro after the Congress of Berlin (1878) and the Balkan Wars (1912-13). Coastally, they live in the Ulcinj (Ulqin) and Bar (Tivar) municipalities which formed part of Venetian Albania. Historical Albanian regions are located in the transboundary mountainous region of Malësia in Tuzi Municipality, south of Montenegrin capital Podgorica. In eastern and northeastern Montenegro, Albanians are concentrated in municipalities of Plav (Plavë) and Gusinje (Gucia) and a smaller community is located in Rožaje Municipality (Rozhajë).[5] The Slavic dialect of Gusinje and Plav shows very high structural influence from Albanian. Its uniqueness in terms of language contact between Albanian and Slavic is explained by the fact that most Slavic-speakers in today's Plav and Gusinje are of Albanian origin.[6]

A mixture of Slavic and Albanian speakers made up the Muslim population of Sandžak (today divided between Serbia and Montenegro) at the end of the nineteenth century. Many Albanian speakers gradually migrated or were relocated to Kosovo and Macedonia, leaving a primarily Slavic-speaking population in the rest of the region (except in a southeastern corner of Sandžak that ended up as a part of Kosovo).[7]

Toponymy[]

A number of placenames in Montenegro are considered to be ultimately derived from or through Albanian. Some cases include:

- Budva, being ultimately derived from the Albanian word butë.[8]

- Ulcinj is considered to be connected with the Albanian word ujk or ulk (meaning wolf in English)[9][10] from Proto-Albanian *(w)ulka.

- Nikšić appears to have developed from the diminutive Albanian name Niksh plus the Slavic suffix ić.[11]

- Kolašin which according to author Rebecca West was originally named Kol I Shen, being Albanian for 'St. Nicholas'.[12]

- Ceklin has been connected to Albanian ceklinë or cektinë which means shallow ground.[13]

- Crmnica first appears in the 13th century under two different names, Crmnica and Kučevo, which is the slavicized variant of an Albanian toponym that meant "red place" (kuq).[14]

- Bojana, a river in southeastern Montenegro, emerged via the Albanian Bunë, and is often seen as indication that Albanian was spoken in the pre-Slavic era in southern Montenegro.[15][16][17]

History[]

14th century[]

In the Middle Ages, Albanians in present-day Montenegro lived in the highlands of Malësia-Brda (both terms mean highlands), around Lake Scodra and coastally in the area known as Albania Veneta. Tuzi, a key Albanian settlement today, is mentioned in 1330 in the Dečani chrysobulls as part of the Albanian (arbanas) katun (semi-nomadic pastoral community) of Llesh Tuzi (Ljesa Tuzi in the original), in an area stretching southwards from modern Tuzi Municipality along the Lake Skadar to a village near modern Koplik. This katund included many communities that later formed their own separate communities: Reçi and his sons, Matagushi, Bushati and his sons, Pjetër Suma and Pjetër Kuçi, first known ancestor of Kuči.[18] In the 1330 chrysobulls, the Hoti tribe is mentioned for first time in Hotina Gora (mountains of Hoti) in the Plav and Gusinje regions on the Lim river basin.[19]

A certain Nicholas Zakarija is first mentioned in 1385 as a Balšić family commander and governor of Budva in 1363.[20] This is considered the first attestation of a member of the noble Albanian Zaharia family.[21] After more than twenty years of loyalty, Nicholas Zakarija revolted in 1386 and became ruler of Budva. However, by 1389 Đurađ II Balšić had recaptured the city.[20]

15th century[]

Beginning in the 15th century, a period of Albanian piracy occurred lasting until the 19th century.These pirates were based mainly in Ulcinj, but were also found in Bar.[22] During this period, Albanian pirates plundered and raided ships, including both Venetian and Ottoman vessels, disrupting the Mediterranean economy and forcing the Ottoman and European powers to intervene. Some of the pirate leaders from Ulcinj, such as Lika Ceni and Hadji Alia, were well known during this period. The Porte had such a problem with the Albanian pirates that they were given the "name-i hümayun" ("imperial letters"),[23] bilateral agreements to settle armed conflicts.[24]The pirates of Ulcinj, known in Italian as lupi di mare Dulcignotti (Alb. ujqit detarë Ulqinakë, 'Ulcinian sea wolves'),[25] were considered the most dangerous pirates in the Adriatic.[26]

In the Middle Ages, the area of Crmnica shows a strong symbiosis of Slavic and Albanian populations.[14] In the second half of 15th century, the Slavic anthroponymy of Crmnica was frequently followed by the Albanian suffix -za. This phenomenon doesn't appear in such widespread form in any other area of Montenegro except for Mrkojevići to the south of Crmnica. It has been interpreted as the result of gradual, centuries-long adoption of Slavic culture by an Albanian-speaking population.[27]

16th century[]

Meshari (Albanian for "Missal") the oldest published book in Albanian was written by Gjon Buzuku, a Catholic Albanian cleric in 1555. Gjon Buzuku was born in the village of Livari in Krajina (Krajë in Albanian) in the Bar region.[28]

In 1565 the Kelmendi rose up against the Ottomans and appear to have done so together with the Kuči and Piperi.[29][30] In 1596, an uprising broke out in the Bjelopavlići plain, which then spread to the Nikšić, Drobnjaci Piva and Gacko. It was suppressed due to lack of foreign support.[31]

17th century[]

In 1613, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the rebel tribes of Montenegro. In response, the tribes of the Vasojevići, Kuči, Bjelopavlići, Piperi, Kastrati, Kelmendi, Shkreli andi Hoti formed a political and military union known as “The Union of the Mountains” or “The Albanian Mountains” .In their shared assemblies, such as the The leaders swore an oath of besa to resist with all their might any upcoming Ottoman expeditions, thereby protecting their self-government and disallowing the establishment of the authority of the Ottoman Spahis in the northern highlands. Their uprising had a liberating character. With the aim of getting rid of the Ottomans from the Albanian territories[32][33]

In the 1614 Convention of Kuçi, 44 leaders mostly from northern Albania and Montenegro took part to organize an insurrection against the Ottomans and ask for assistance by the Papacy.[34][35] That same year, the Kelmendi along with the tribes of Kuči, Piperi and Bjelopavlići, sent a letter to the kings of Spain and France claiming they were independent from Ottoman rule and did not pay tribute to the empire.[36][37]

In 1658, the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Klimenti, Hoti and Gruda allied themselves with the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called "Seven-fold banner" or "alaj-barjak", against the Ottomans.[38]

A Franciscan report of the 17th century illustrates the final stages of the acculturation of some Albanian tribes in Brda. Its author writes that the Bratonožići (Bratonishi), Piperi (Pipri) , Bjelopavlići (Palabardhi) and Kuči (Kuçi):" nulla di meno essegno quasi tutti del rito serviano, e di lingua Illrica ponno piu presto dirsi Schiavoni, ch' Albanesi " (since almost all of them use the Serbian rite and the Illyric (Slavic) language, soon they should be called Slavs, rather than Albanians)[39]

In 1685 the Mainjani tribe participated in the Battle of Vrtijeljka on the side of the Venetians. The battle resulted in defeat.[40]

In 1688 the tribes of Kuçi, Kelmendi and Pipri rose up and captured the town of Medun, defeating 2 Ottoman counter-assaults and capturing many supplies in the process before retreating.[41]

18th century[]

The Arbanasi people in the Zadar region are thought to have hailed from the Catholic Albanian inhabitands of the region of Shestan, specifically from the villages of Briska (Brisk), Šestan (Shestan), Livari (Ljare), and Podi (Pod) having settled the Zadar area in 1726–27 and 1733 on the decision of Archbishop Vicko Zmajević of Zadar, in order to repopulate the land.[42]

A period of Albanian semi-independence started in the 1750s with the Independent Albanian Pashas. In 1754 the autonomous Albanian Pashalik of Bushati family would be established with center the city of Shkodra called Pashalik of Shkodra. The Bushati family initially dominated the Shkodër region through a network of alliances with various highland tribes and later expanded in huge areas in today's Montenegro, Northern Albania, Macedonia, southern Serbia.

Kara Mahmud Bushati attempted to establish a de juro independent principality and expand the lands under his control by playing off Austria and Russia against the Sublime Porte. In 1785, Kara Mahmud's forces attacked Montenegrin territory, and Austria offered to recognize him as the ruler of all Albania if he would ally himself with Vienna against the Sublime Porte. Seizing an opportunity, Kara Mahmud sent the sultan the heads of an Austrian delegation in 1788, and the Ottomans appointed him governor of Shkodër. When he attempted to wrest land from Montenegro in 1796, however, he was defeated and killed by an ambush in northern Montenegro.

Kara Mahmud's brother, Ibrahim Bushati, cooperated with the mountain tribes and brought a large area in Balkans under his control like Kara Mahmud Bushati.[43] At its peak during the reign of Kara Mahmud Bushati the pashalik encompassed much of Albania, most of Kosovo, western Macedonia, southeastern Serbia and most of Montenegro. Up to 1830 the Pashalik of Shkodra controlled most of the above lands including Southern Montenegro.[44][45] The pashalik was dissolved in 1831.

British author Rebecca West visited the town of Kolašin in the 1930s where she learned that in the 18th century, Catholic Albanians and Orthodox Montenegrins lived in peace. In 1858, however, several Montenegrin tribes attacked the town and killed all inhabitants who kept their Albanian identity or who were Muslim.[46]

19th century[]

On October 26, 1851, the Arnaut chieftain Gjonlek from Nikšić was traveling with 200 Arnauts, given the task of defending Ottoman Albanian interests. They were attacked by Montenegrin forces from Gacko. On November 11, 1851, Montenegrin forces numbering 30 crossed the Moraca river and attacked the Albanian Ottoman citadel, under Selim Aga, with 27 men. Five were killed and four wounded while Selim Aga pulled back, wounded, into his house. The next morning, he returned to counter the Montenegrins. The Pasha of Scutari immediately began gathering troops.[47]

In 1877, Nikšić was annexed by the Montenegrins in accordance with the Treaty of Berlin.[48][49] American author William James Stillman (1828-1901) who traveled in the region at the time writes in his biography of the Montenegrin forces who, on the orders of the Prince, began to bomb the Studenica fortress in Nikšić with artillery. Around 20 Albanian nizams were inside the fortress who resisted and when the walls breached, they surrendered and asked Stillman if they were going to be decapitated. An Albanian accompanying Stillman translated his words saying they were not going to be killed in which the Albanians celebrated.[50] Shortly after the treaty, the Montenegrin prince began expelling the Albanians from Nikšić, Žabljak and Kolašin who then fled to Turkey, Kosovo (Pristina)[51] and Macedonia.[52] The Montenegrin forces also robbed the Albanians before the expulsion.[53] After the fall of Nikšić, Prince Nicholas I wrote a poem of the victory.[54] After the territorial expansion of Montenegro towards the Ottoman territories in 1878, Albanians for the first time became citizens of that country. Albanians that obtained Montenegrin citizenship were Muslims and Catholics, and lived in the cities of Bar and Ulcinj, including their surroundings, in the bank of river Bojana and shore of Lake Skadar, as well as in Zatrijebač.[55]

On the eve of conflict between Montenegro and the Ottomans (1876–1878), a substantial Albanian population resided in the Sanjak of İşkodra.[56] In the Montenegrin-Ottoman war that ensued, strong resistance in the towns of Podgorica (majority Muslim at the time, with a substantial portion being Albanian) and Spuž toward Montenegrin forces was followed by the expulsion of their Albanian and Slavic Muslim populations who resettled in Shkodër.[57] [57] These populations resettled in Shkodër city and its environs.[58][59] A smaller Albanian population formed of the wealthy elite voluntarily left and resettled in Shkodër after Ulcinj's incorporation into Montenegro in 1880.[59][58]

On January 31, 1879, Montenegrin teacher Shcepan Martinovied informed the government of Cetinje that the Muslims of Nikšić desired a school.[60] The Ottomans had opened schools in Nikšić , among other neighboring regions, in the 17th and 18th century.[61]

In 1879, Zenel Ahmet Demushi of the Geghyseni tribe, fought with 40 members of the family against Montenegrin forces led by Marko Miljanov in Nikšić .[62] The conflict intensified in 1880 when the Albanian irregulars fought under Ali Pash Gucia against the Montenegrin forces led by the brother of Marko Milajnov, Teodor Miljanov, the battle lasting five hours, according to letters written by two local Albanians from Shkodër who participated in the battle.[63]

The Battles for Plav and Gusinje were armed conflicts between the Principality of Montenegro and Ottoman irregular armies (pro-Ottoman Albanian League of Prizren) that broke out following the decision of the Congress of Berlin (1878) that the territories of Plav and Gusinje (part of former Scutari Vilayet) be ceded to Montenegro. The conflicts took place in this territory between 9 October 1879 and 8 January 1880. The following battles were fought: the Velika attacks (9 October–22 November 1879), the Battle of Novšiće (4 December 1879) and the Battle of Murino (8 January 1880).

In 1880 a battle was fought between the Ottoman forces of Dervish Pasha and Albanian irregulars at the region of Kodra e Kuqe, close to Ulcinj. The area of Ulcinj had been handed over to Montenegro by the Ottomans after the Albanians previously fought against the annexions of Hoti and Grude.[64] The Great powers instead pressured the Ottomans to hand over the area of Ulcinj, but also here the Albanians refused. Eventually the Great powers forced the Ottomans to take actions against the League of Prizren, ending the resistance and successfully handing over the town of Ulcinj to Montenegro.[65][66]

In 1899, the government in Montenegro arrested Albanians in Nikšić and Danilovgrad out of fear that the Malesori would attack the Young Turks in the region, and the captives were held for more than six months in prison.[67]

20th century[]

The Bulgarian foreign ministry compiled a report about the five kazas (districs) of the sanjak of the Novi Pazar in 1901-02. According to the Bulgarian report, the kazas of Akova and Kolašin were almost entirely populated by Albanians. In the kaza of Akovo there were 47 Albanian villages which had 1,266 households, whereas Serbs lived in 11 villages which had 216 households.[68] The town of Akova (Bijelo Polje) had 100 Albanian and Serb households. The kaza of Kolašin had 27 Albanian villages with 732 households and 5 Serb villages with 75 households. The administrative centre of the kaza, Šahovići, had 25 Albanian households. [69]

On March 24th 1911, an Albanian uprising broke out in Malësia. During one of its battles, the Battle of Deçiq (6 April), the Albanian flag was raised for the first time in possibly over 400 years in the Deçiq mountain near Tuzi. It was raised by Ded Gjo Luli on the peak of Bratila after victory was secured. The phrase "Tash o vllazën do t’ju takojë të shihni atë që për 450 vjet se ka pa kush" (Now brothers you have earned the right to see that which has been unseen for 450 years) has been attributed to Ded Gjo Luli by later memoirs of those who were present when he raised the flag.[70] It was one of three banners brought to Malësia by Palokë Traboini, student in Austria. The other two banners were used by Ujka of Gruda and Prelë Luca of Triepshi.[71]

On 11 May, Shefqet Turgut Pasha issued a general proclamation which declared martial law and offered an amnesty for all rebels (except for Malësor chieftains) if they immediately return to their homes.[72] After Ottoman troops entered the area Tocci fled the empire abandoning his activities.[73]. Three days later, he ordered his troops to again seize Dečić.[74] Sixty Albanian chieftains rejected Turgut Pasha's proclamation on their meeting in Podgorica on 18 May.[75] After almost a month of intense fightings rebels were trapped and their only choices were either to die fighting, to surrender or to flee to Montenegro.[76] Most of the rebels chose to flee to Montenegro which became a base for large number of rebels determined to attack the Ottoman Empire.[77] Ismail Kemal Bey and Tiranli Cemal bey traveled from Italy to Montenegro at the end of May and met the rebels to convince them to adopt the nationalistic agenda which they eventually did.[78][79]

After the battle, at the initiative Ismail Qemali[80] the assembly of the tribal leaders of the revolt was held in a village in Montenegro (Gerče) on 23 June 1911 to adopt the "Gërçe Memorandum" [81]) with their requests both to Ottoman Empire and Europe (in particular to the Great Britain).[82] This memorandum was signed by 22 Albanian chieftains, four from each tribe of Hoti, Grude and Shkrel, five from Kastrati, three from Klementi and two from Shale.[83]

The Plav–Gusinje massacres (1912–1913) occurred between late 1912 and March 1913 in the areas of the modern Plav and Gusinje municipalities and adjacent areas. More than 1,800 locals, mostly Muslim Albanians from these two regions were killed and 12,000 were forced to convert to Orthodoxy by the military administration put in charge of these regions by the Kingdom of Montenegro which had annexed them during the First Balkan War.[84][85]

After the Balkan Wars, new territories inhabited by Albanians became part of Montenegro. Montenegro then gained a part of Malesija, respectively Hoti and Gruda, with Tuzi as center, Plav, Gusinje, Rugovo, Peja and Gjakova.[55] During World War I, Albanian immigrants from Nikšić who had been expelled to Cetinje sent a letter to Isa Boletini saying that they risked starving if he did not send them money for food.[86]

During the Serbian army's second occupation of Rožaje, which took place in 1918-1918, seven hundred Albanian citizens were slaughtered in Rožaje (Sandžak). This was also done in order to quell uprisings in the Plav and Gusinje districts, which resulted in a large influx of Albanians migrating to Albania.[87][88]

With the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after World War I, Albanians in Montenegro became discriminated. The position would improve somewhat in Tito's Yugoslavia. In the mid-twentieth century, 20,000 Albanians lived in Montenegro and their number would grow by the end of the century. By the end of the 20th century the number of Albanians began to fall as a result of immigration.[55]

During the Second World War, Chetnik forces based in Montenegro conducted a series of ethnic cleansing operations against Muslims in the Bihor region. In May of 1943, an estimated 5400 Albanian men, women and children in Bihor were massacred by Chetnik forces under Pavle Đurišić.[89] The notables of the region then published a memorandum and declared themselves to be Albanians. The memorandum was sent to Prime Minister Ekrem Libohova whom they asked to intervene so the region could be united to the Albanian kingdom.[90]

The Bar massacre was the killings of an unknown number of mostly ethnic Albanians from Kosovo Yugoslav Partisans in late March or early April 1945 in Bar, a municipality in Montenegro, at the end of World War II. Yugoslav sources put the number of victims at 400[91] while Albanian sources put the figure at 2,000 killed in Bar alone.[92] According to Croatian historian Ljubica Štefan, the Partisans killed 1,600 Albanians in Bar on 1 April after an incident at a fountain.[93] There are also accounts claiming that the victims included young boys.[94] Other sources cited that the killing started en route for no apparent reason and this was supported by the testimony of Zoi Themeli in his 1949 trial.[95] Themeli was a collaborator who worked as an important official of the Sigurimi, the Albanian secret police.[96] After the massacre, the site was immediately covered in concrete by the Yugoslav communist regime and built an airport on top of the mass grave.[94]

Modern period[]

On 26 November 2019, an earthquake struck Albania. In Montenegro, Albanians from Ulcinj were involved in a major relief effort sending items such as food, blankets, diapers and baby milk through a local humanitarian organisation Amaneti and in Tuzi through fundraising efforts.[97]

Demographics[]

Albanians in Montenegro are settled in the southeastern and eastern parts of the country. Ulcinj Municipality, consisting Ulcinj (Albanian: Ulqin) with the surroundings and Ana e Malit region, along with the newly-formed Tuzi Municipality, are the only municipalities where Albanians are the majority (71% and 68% of the populations respectively). A large number of Albanians also live in the following regions: Bar (Tivar) and Skadarska Krajina (Krajë) in Bar Municipality (2,515 Albanians or 6% of the population), Plav (Plavë) and Gusinje (Guci) in Plav Municipality (2,475 or 19%) and Rožaje (Rozhajë) in Rožaje Municipality (1,158 or 5%).[4]

The largest Albanian settlement is Ulcinj, followed by Tuzi.

Municipalities with an Albanian majority[]

Of the 24 municipalities in the country, 2 have an ethnic Albanian majority.

| Emblem | Municipality | Area km² (sq mi) |

Settlements | Population (2011) | Mayor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | |||||

| Ulcinj Ulqin |

255 km2 (98 sq mi) | 41 | 19,921 | 70.66% | Ljoro Nrekić (DPS) | |

|

Tuzi Tuz |

236 km2 (91 sq mi) | 37 | 12,096 | 68.45% | Nik Gjeloshaj (AA) |

| — | 2 | — | 78 | 32,017 | — | — |

Anthropology[]

The Albanians in Montenegro are Ghegs.

Tribes[]

The historical Albanian tribes which exist in Montenegro up to the modern era are: Hoti, Gruda, Trieshi, Koja.[98][full citation needed]

Other Albanian tribes also existed in the past, but either formed other tribes or assimilated into the neighbouring Slavic population. Examples include Mataruge and Španje in Old Herzegovina, Kryethi and Pamalioti around the city of Ulcinj, Mahine above Budva, Goljemadi in Old Montenegro, as well as tribes who inhabited the Brda area, including Bytadosi, Bukumiri, Malonšići, Macure, Mataguzi, Drekalovići, Kakarriqi, Rogami, Kuçi, Piperi, Bratonožići, Vasojevići and Bjelopavlići, the latter five now identifying as Slavic.

Culture[]

Montenegrin Albanian culture in this region is closely related to the culture of Albanians in Albania, and the city of Shkodër in particular. Their Albanian language dialect is Gheg as of Albanians in Northern Albania.

Religion[]

According to the 2003 census, 73.37% of Albanians living in Montenegro were Muslim and 26.08% were Roman Catholic.[99] The religious life of Muslim Albanians is organized by the Islamic Community of Montenegro, comprising not only Albanians, but also other Muslim minorities in Montenegro.[100] Catholic Albanians, generally living in Malesija, Šestani and some in the Bar and Ulcinj municipalities, are members of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bar, whose members are mainly Albanians, but which also includes a small number of Slavs. The current archbishop, Zef Gashi, is an ethnic Albanian.[100]

During the Middle ages, Eastern Orthodox Albanians also inhabited Montenegro, with some examples including the Mahine near Budva, which had as its gathering place the Podmaine monastery, and the Mataguzi south of Podgorica whose leaders in 1468 donated to the Vranjina Monastery a land area between Rijeka Plavnica and Karabež on the shores of Lake Skadar.[101]

Language[]

Albanians in Montenegro speak the Gheg Albanian dialect, namely the northwestern variant, while according to the 2011 Census, there are 32,671 native speakers of the Albanian language (or 5.27% of the population).[4]

According to Article 13 of the Constitution of Montenegro, Albanian language (alongside Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian) is a language in official use, officially recognized as minority language.[102]

Education[]

The government of Montenegro provides Albanian-language education in the local primary and secondary schools. There is one department in the University of Montenegro, located in Podgorica, offered in Albanian, namely teacher education[55]

Politics[]

The first political party created by Albanians in this country is the Democratic League in Montenegro, founded by Mehmet Bardhi in 1990. Most Albanians support the country's integration into the EU: during the 2006 Montenegrin independence referendum, in Ulcinj Municipality, where Albanians at that time accounted over 72% of the population, 88.50% of voters voted for an independent Montenegro. Overall, the vote of the Albanian minority secured the country's secession from Serbia and Montenegro.[103]

In 2008, the Albanian National Council (Albanian: Këshilli Kombëtar i Shqiptarëve, abb. KKSH) was established to represent the political interests of the Albanian community. The current chairman of the KKSH is Genci Nimanbegu.

Prominent Individuals[]

See also[]

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

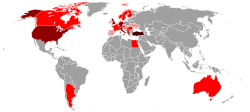

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

|

Christianity (Catholicism · Italo-Albanian Church · Albanian Greek-Catholic Church · Orthodoxy) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Cham · Lab) |

|

History of Albania (Origin of the Albanians) |

- Serbo-Montenegrins in Albania

- Malësia

- Malesija, Montenegro

- Albanians

Gallery[]

Albanians in Montenegro from 1921 to 2011.

Percent of Albanians by municipalities, 1953.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1961.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1971.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1981.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 1991.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 2003.

Percent of Albanians by settlements, 2011.

References[]

- ^ "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" [Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011] (PDF) (Press release) (in Serbo-Croatian). Statistical office, Montenegro. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). July 12, 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World music: the rough guide. Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Most of the ethnic Albanians that live outside the country are Ghegs, although there is a small Tosk population clustered around the shores of lakes Presp and Ohrid in the south of Macedonia.

- ^ a b c Stanovništvo Crne Gore prema polu, tipu naselja, nacionalnoj, odnosno etničkoj pripadnosti, vjeroispovijesti i maternjem jeziku po opštinama u Crnoj Gori – monstat.org

- ^ Morrison 2018, p. 66

- ^ Matthew C., Curtis (2012). Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence. The Ohio State University. p. 140.

- ^ Dragostinova, Theodora; Hashamova, Yana (2016-08-20). Beyond Mosque, Church, and State: Alternative Narratives of the Nation in the Balkans. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-386-135-6.

- ^ Eichler, Ernst; Hilty, Gerold; Löffler, Heinrich; Steger, Hugo; Zgusta, Ladislav (2008). Namenforschung / Name Studies / Les noms propres. 1. Halbband. Walter de Gruyter. p. 718. ISBN 978-3110203424.

- ^ Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians. Wiley. p. 244. ISBN 9780631146711. "Names of individuals peoples may have been formed in a similar fashion, Taulantii from ‘swallow’ (cf. the Albanian tallandushe) or Erchelei the ‘eel-men’ and Chelidoni the ‘snail-men’. The name of the Delmatae appears connected with the Albanian word for ‘sheep’ delmë) and the Dardanians with for ‘pear’ (dardhë). Some place names appear to have similar derivations, including Olcinium (Ulcinj from ‘wolf’ (ukas), although the ancients preferred a connection with Cholchis."

- ^ Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan (1963). "The Position of Albanian". Ancient Indo-European Dialects. University of California Press. p. 108.

- ^ Gashi, Skënder (2015). ONOMASTIC-HISTORICAL RESEARCH ON EXTINCT AND ACTUAL MINORITIES OF KOSOVA. ASHAK. p. 245.

- ^ West, Rebecca (2007). Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-04268-7. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Zbornik Matice srpske za filologiju i lingvistiku. Matica. 1994. p. 498. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ a b Milan Šufflay (2000). Izabrani politički spisi. Matica hrvatska. p. 218. ISBN 9789531502573. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Ismajli 2015, p. 474.

- ^ Katičić 1976, p. 186

- ^ Demiraj 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Pulaha 1975, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Ahmetaj 2007, p. 170.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 392.

- ^ Anamali 2002, p. 268.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (2015). Agents of Empire Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean World (PDF). Oxford University press. p. 149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-12. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ Maria Pia Pedani. The Ottoman-Venetian Border (15th-18th Centuries). p. 46

- ^ Gábor Ágoston; Bruce Masters (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 9781438110257.

- ^ "Varri i Marës, çërnojeviqet dhe shqiptarët në mesjetë". Konica.al. 10 August 2019.

- ^ Beach, Frederick Converse; Rines, George Edwin (1903). The Americana : a universal reference library, comprising the arts and sciences, literature, history, biography, geography, commerce, etc. of the world. New York : Scientific American Compiling Dept. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

Dulcigno, dool-chen'yo, Montenegro, a small seaport town on the Adriatic. The in- habitants, formerly notorious under the name of Dulcignottes, as the most dangerous pirates of the Adriatic, are now engaged in commerce or in the fisheries of the river Bojana. Pop. 5,102.

- ^ Pulaha, Selami (1972). "Elementi shqiptar sipas onomastikës së krahinave të sanxhakut të Shkodrës [The Albanian element in view of the anthroponymy of the sanjak of Shkodra]". Studime Historike: 84–5. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Igla, Birgit; Boretzky, Norbert; Stolz, Thomas (2001-10-24). Was ich noch sagen wollte. Akademie Verlag. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-05-003652-6. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Elsie 2015, p. 28. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFElsie2015 (help)

- ^ Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 97.

- ^ Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. "Преокрет у држању Срба". Историја српског народа (in Serbian). Belgrade: Јанус.

- ^ Kola, Azeta (2017). "FROM SERENISSIMA'S CENTRALIZATION TO THE SELFREGULATING KANUN: THE STRENGTHENING OF BLOOD TIES AND THE RISE OF GREAT TRIBES IN NORTHERN ALBANIA FROM 15TH TO 17TH CENTURY". Acta Histriae: 369. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Mala, Muhamet (2017). "The Balkans in the anti-Ottoman projects of the European Powers during the 17th Century". Studime Historike (1–02): 276.

- ^ Dokumente të shekujve XVI-XVII për historinë e Shqipërisë (in Albanian). Akademia e Shkencave e RPS të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë. 1989. p. 9. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Studime Historike (in Albanian). 1967. p. 127. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Kulišić, Špiro (1980). O etnogenezi Crnogoraca (in Montenegrin). Pobjeda. p. 41. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Lambertz, Maximilian (1959). Wissenschaftliche Tätigkeit in Albanien 1957 und 1958. Südost-Forschungen. S. Hirzel. p. 408. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Mitološki zbornik. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. pp. 24, 41–45.

- ^ Ramaj, Albert. Poeta nascitur, historicus fit -Ad honorem Zef Mirdita (PDF). p. 132.

Në mënyrë domethënëse, një tekst françeskan i shek. XVII, pasi pohon se fi set e Piperve, Bratonishëve, Bjelopavliqëve e Kuçëve ishin shqiptare, shton se: “megjithatë, duke qenë se thuajse që të gjithë ata ndjekin ritin serbian (ortodoks) dhe përdorin gjuhën ilirike (sllave), shumë shpejt do mund të quhen më shumë Sllavë, se sa Shqiptarë...Ma favellando delle quattro popolationi de Piperi, Brattonisi, Bielopaulouicchi e Cuechi, liquali et il loro gran ualore nell’armi danno segno di esser de sangue Albanese e a tale dalli Albanesi sono tenuti

- ^ SANU (1971). "Editions speciales". 443. Naučno delo: 151. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Elsie, Robert (30 May 2015). The tribes of Albania: History,Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78453-401-1.

- ^ Barančić, Maximilijana (2008). "Arbanasi i etnojezični identitet" (in Croatian). Zadar: Croatica et Slavica Iadertina; Sveučilište u Zadru.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ottoman Albanianswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Vickers 1999, p. 18

- ^ Iseni 2008, p. 120

- ^ ANDRÉ-LOUIS SANGUIN, SANGUIN (2011). MONTENEGRO IN REBECCA WEST'S BLACK LAMB AND GREY FALCON: THE LITERATURE OF TRAVELLERS AS A SOURCE FOR POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY CRNA GORA U DJELU REBECCE WEST BLACK LAMB AND GREY FALCON: PUTOPISI KAO IZVOR PODATAKA U POLITIČKOJ GEOGRAFIJI. 1Sveučilište Paris-Sorbonne / University of Paris-Sorbonne. p. 257. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Samtiden: skildringar från verldstheatern (in Swedish) (In Swedish "Den 26 Oktober 1851 tilldrog sig nemligen, att Arnaut-chefen Gjulek från Niksic, hvilken skulle försvara landet mot Montenegrinerna och hålla själv staden i lydnad, hade med 200 arnauter, dem han hemtat till förstärkning från Mostar, blifvit överfallen af en stark Montenegrinsk Ceta i trakten af Gatsko. " Translation: On October 26, 1851, Arnaut commander Gjulek of Niksic, who would defend the country against the Montenegrin and keep the city in obedience, had agreed, with 200 arnauts, which he had taken to reinforce Mostar, to have been attacked by a strong Montenegrin Ceta in the neighborhood of Gatsko. ed.). tryckt hos P. G. Berg. 1858. p. 478. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Qosja, Rexhep (1999). Kosova në vështrim enciklopedik (in Albanian). Botimet Toena. p. 81. ISBN 978-99927-1-170-5. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 559. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Stillman, William James (1877). The Autobiography of a Journalist, Volume II by William James Stillman - Full Text Free Book (Part 3/5). Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Kultura popullore (in Albanian) (Translation: 118/5000 the process of expelling Albanians from their lands in Koloshin, Niksic Field, Zabjak and elsewhere ”. ed.). Akademia e Shkencave e RSH, Instituti i Kulturës Popullore. 1991. p. 25. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Maloku, Enver (1997). Dëbimet e shqiptarëve dhe kolonizimi i Kosovës (1877-1995) (in Albanian) (Montenegrin army violence and property theft forced them to flee from Kolasin, Niksic, Shpuza, ... ed.). Qendra për Informim e Kosovës. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ ILLYRIAN LETTERS. 1878. p. 187. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Istorijski Leksikon Crne Gore, Grup of authors, Daily press: Podgorica, 2006 [[Speciale:BurimeteLibrave/867706169X|ISBN 86-7706-169-X]]

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 22. "Meanwhile Austria-Hungary's occupation of Bosnia-Hercegovina, which had been conceded at the congress, acted as a block to Montenegrins territorial ambitions in Hercegovina, whose Orthodox Slav inhabitants were culturally close to the Montenegrins. Instead Montenegro was able to expand only to the south and east into lands populated largely by Albanians – both Muslims and Catholics – and Slav Muslims. Along the coast in the vicinity of Ulcinj the almost exclusively Albanian population was largely Muslim. The areas to the south and east of Podgorica were inhabited by Albanians from the predominantly Catholic tribes, while further to the east there were also concentrations of Slav Muslims. Podgorica itself had long been an Ottoman trading centre with a partly Turkish, but largely Slav Muslim and Albanian population. To incorporate such a population was to dilute the number of Montenegrins, whose first loyalties lay with the Montenegrin state and Petrović dynasty, not that this was seen as sufficient reason for the Montenegrins to desist from seeking to obtain further territory."; p.23 "It was only in 1880 after further fighting with local Albanians that the Montenegrins gained an additional 45 km, stretch of seaboard extending from just north of Bar- down to Ulcinj. But even after the Congress of Berlin and these later adjustments, certain parts of the Montenegrin frontier continued to be disputed by Albanian tribes which were strongly opposed to rule by Montenegro. Raiding and feuding took place along the whole length of the porous Montenegrin-Albanian border."

- ^ a b Blumi 2003, p. 246. "What one sees over the course of the first ten years after Berlin was a gradual process of Montenegrin (Slav) expansion into areas that were still exclusively populated by Albanian-speakers. In many ways, some of these affected communities represented extensions of those in the Malisorë as they traded with one another throughout the year and even inter-married. Cetinje, eager to sustain some sense of territorial and cultural continuity, began to monitor these territories more closely, impose customs officials in the villages, and garrison troops along the frontiers. This was possible because, by the late 1880s, Cetinje had received large numbers of migrant Slavs from Austrian-occupied Herzegovina, helping to shift the balance of local power in Cetinje's favor. As more migrants arrived, what had been a quiet boundary region for the first few years, became the center of colonization and forced expulsion." ; p.254. footnote 38. "It must be noted that, throughout the second half of 1878 and the first two months of 1879, the majority of Albanian-speaking residents of Shpuza and Podgoritza, also ceded to Montenegro by Berlin, were resisting en masse. The result of the transfer of Podgoritza (and Antivari on the coast) was a flood of refugees. See, for instance, AQSH E143.D.1054.f.1 for a letter (dated 12 May 1879) to Dervish Pasha, military commander in Işkodra, detailing the flight of Muslims and Catholics from Podgoritza."

- ^ a b Gruber 2008, pp. 142. "Migration to Shkodra was mostly from the villages to the south-east of the city and from the cities of Podgorica and Ulcinj in Montenegro. This was connected to the independence of Montenegro from the Ottoman Empire in the year 1878 and the acquisition of additional territories, e.g. Ulcinj in 1881 (Ippen, 1907, p. 3)."

- ^ a b Tošić 2015, pp. 394–395. "As noted above, the vernacular mobility term 'Podgoriçani' (literally meaning 'people that came from Podgoriça', the present-day capital of Montenegro) refers to the progeny of Balkan Muslims, who migrated to Shkodra in four historical periods and in highest numbers after the Congress of Berlin 1878. Like the Ulqinak, the Podgoriçani thus personify the mass forced displacement of the Muslim population from the Balkans and the 'unmixing of peoples' (see e.g. Brubaker 1996, 153) at the time of the retreat of the Ottoman Empire, which has only recently sparked renewed scholarly interest (e.g. Blumi 2013; Chatty 2013)." ; p. 406.

- ^ Redžepagić 1970, p. 102.

- ^ Redžepagić 1970, p. 36.

- ^ Brahim Uk Demushi, personalitet i shquar i Tropojës. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Prizrenit, Lidhja Shqiptare e (1978). Me pushkë dhe penë për liri e pavarësi (in Albanian) (Translation: But the peak of this war reached the battle of Nikshiiq in early January 1880. ed.). Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nëntori". pp. 120, 115. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Library of Congress Subject Headings. Library of Congress. 2012.

- ^ Office, Library of Congress Cataloging Policy and Support (2009). Library of Congress Subject Headings. Library of Congress, Cataloging Distribution Service.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (24 April 2015). The Tribes of Albania,: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857739322.

- ^ Shpuza, Gazmend (1999). Në prag të pavarësisë (in Albanian) (... fearing that the Highlanders would attack the Young Turk troops from the territories of Montenegro, the third, arrested and interned the Albanians in Niksic and Danilovgrad, lasting up to six months ed.). Eagle Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-891654-04-6. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Bartl, 1968 & 63:Die Kaza Bjelopolje ( Akova ) zählte 11 serbische Dörfer mit 216 Häusern , 2 gemischt serbisch - albanische Dörfer mit 25 Häusern und 47 albanische Dörfer mit 1 266 Häusern . Bjelopolje selbst hatte etwa 100 albanische und serbische.

- ^ Bartl, 1968 & 63:Die Kaza Kolašin zählte 5 serbische Dörfer mit 75 Häusern und 27 albanische Dörfer mit 732 Häusern .

- ^ Verli, Marenglen (2014). "The role of Hoti in the uprising of the Great Highlands". Studime Historike (1–2).

- ^ Martin, Traboini (1962). "Mbi kryengritjen e Malsisë së Madhe në vitet 1911-1912". In Pepo, Petraq (ed.). Kujtime nga lëvizja për çlirimin kombetar (1878-1912). University of Tirana. p. 446.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 186

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 186

- ^ Treadway 1983, p. 77

government called upon Shefqet Turgut Pasha...on 11 May he proclaimed martial law...On the third day however, the impatient general ordered his troops to seize the important hill of Dečić overlooking Tuzi.

- ^ Treadway 1983, p. 77

In they Podgorica declarationof 18 May sixty Albanian chiefs rejected Turgut's demands...

- ^ Treadway 1983, p. 77

During the month of intense fighting...By the end of June the Catholic insurgents jointed by the powerful Mirdite clans, were trapped...They had but three choices left to them: to surrender, to die where they were or to flee across the border into Montenegro.

- ^ Treadway 1983, p. 77

Most chose the last option. Once again became a haven for large body of insurgent forces determined to make war on Ottoman Empire.

- ^ Études balkaniques. Édition de lA̕cadémie bulgare des sciences. 2002. p. 49.

The memorandum adopted at a general assembly in Gerçë a month later doubtless bears the penmanship of Ismail Qemali, who arrived in Montenegro from Italy at the end of May.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 186, 187

Meanwhile Ismail Kemal and Tiranli Cemal Bey personally visited rebellious Malisors in Montenegro to encourage them to accept a nationalistic program.... The Ghegs of Iskodra had embraced nationalistic program.

- ^ Isaković, Antonije (1990). Kosovsko-metohijski zbornik. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 298. ISBN 9788670251052.

У то време стигао je у Црну Гору албански нрвак Исмаил Кемал Bej да би се састао са главарима побушених Малисора. На н>егову инищцативу дошло je до састанка побунэених Малисора у селу Герче у Црно) Гори.

- ^ Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton University Press. p. 417. ISBN 9780691650029. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

The Gerche memorandum, referred to often as "The Red Book" because of the color of its covers

- ^ Treadway 1983, p. 78

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 187

Twenty two Albanians signed the memorandum, including four each from the fises of Grude, Hoti and Skrel; five from Kastrati; three from Klement, and two from Shale

- ^ Poláčková & Van Duin 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Müller 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Gjurmime albanologjike: Seria e shkencave historike (in Albanian). Instituti. 1988. p. 251. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Mulaj, Klejda (2008-02-22). Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: Nation-State Building and Provision of In/Security in Twentieth-Century Balkans. Lexington Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7391-4667-5.

- ^ Banac, Ivo (2015-06-09). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. pp. 298 snippet view. ISBN 978-1-5017-0194-8.

- ^ Kaba, Hamit (2013). "RAPORTI I STAVRO SKËNDIT DREJTUAR OSS' NË WASHINGTON D.C "SHQIPËRIA NËN PUSHTIMIN GJERMAN". STAMBOLL, 1944". Studime Historike: 275.

- ^ Džogović, Fehim (2020). "NEKOLIKO DOKUMENATA IZ DRŽAVNOG ARHIVA ALBANIJE U TIRANI O ČETNIČKOM GENOCIDU NAD MUSLIMANIMA BIHORA JANUARA 1943". ALMANAH - Časopis za proučavanje, prezentaciju I zaštitu kulturno-istorijske baštine Bošnjaka/Muslimana (in Bosnian) (85–86): 329–341. ISSN 0354-5342.

- ^ "Željko Milović-DRUGI SVJETSKI RAT". Montenengrina Digitalna Biblioteka.

- ^ "Massive Grave of Albanian Victims of Tivari Massacre uncovered". Albanian Telegraphic Agency. 19 September 1996. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Ljubica Štefan (1999). Mitovi i zatajena povijest. K. Krešimir. ISBN 978-953-6264-85-8.

- ^ a b Bytyci, Enver (2015). Coercive Diplomacy of NATO in Kosovo. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781443872720.

- ^ Fevziu, Blendi (2016-02-01). Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857729088.

- ^ Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume III: Albania as Dictatorship and Democracy, 1945-99. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 343. ISBN 1845111052.

- ^ "Mali i Zi me sy nga Shqipëria- vijojnë ndihmat nga qytete, institucione dhe individë" (in Albanian). TRT. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Recherches albanologiques: Folklore et ethnologie (in French). Pristina: Instituti Albanologijik i Prishtinës. 1982.

- ^ "Montenegrin Census' from 1909 to 2003 - Aleksandar Rakovic". www.njegos.org.

- ^ a b Bieber, Florian (2003). Montenegro in Transition – Problems of Identity and Statehood. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-8329-0072-4.

- ^ Kovijanić, Risto (1974). Pomeni crnogorskih plemena u Kotorskim spomenicima, XIV-XVI vijek. Historical Institute of Montenegro. p. 57. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ KUSHETUTA E MALIT TË ZI – minmanj.gov.me

- ^ "The Minority Report: Jobless Ethnic Albanians "Let Down by the State"".

Bibliography[]

- Ahmetaj, Mehmet (2007). "Toponymy of Hoti". Studime Albanologjike. 37.

- Curtis, Matthew (2012). Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence. Ohio State University.

- Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: A reader of Historical texts, 11th–17th centuries. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447047838.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2018). Nationalism, Identity and Statehood in Post-Yugoslav Montenegro. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1474235198.

- Morozova, Maria (2019). "Language Contact in Social Context: Kinship Terms and Kinship Relations of the Mrkovići in Southern Montenegro". Journal of Language Contact. 12 (2): 305–343. doi:10.1163/19552629-01202003.

- Morozova, Maria; Rusakov, Alexander (2018). "SLAVIC-ALBANIAN INTERACTION IN VELJA GORANA: PAST AND PRESENT OF A BALANCED LANGUAGE CONTACT SITUATION". International Scientific Conference "Multiculturalism and Language Contact".

- Pulaha, Selami (1975). "Kontribut për studimin e ngulitjes së katuneve dhe krijimin e fiseve në Shqipe ̈rine ̈ e veriut shekujt XV-XVI' [Contribution to the Study of Village Settlements and the Formation of the Tribes of Northern Albania in the 15th century]". Studime Historike. 12.

- Redžepagić, Jašar (1970). Zhvillimi i arësimit dhe i sistemit shkollor të kombësisë shqiptare në teritorin e Jugosllavisë së sotme deri në vitin 1918. Enti i teksteve dhe i mjeteve mësimore i Krahinës Socialiste Autonome të Kosovës.

- Albanian diaspora by country

- Ethnic groups in Montenegro

- Montenegrin people of Albanian descent