Amistad (film)

| Amistad | |

|---|---|

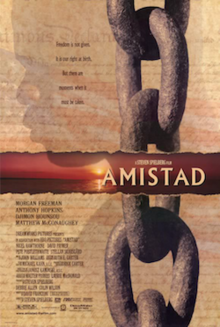

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Written by | David Franzoni |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | HBO Pictures |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 154 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $36 million |

| Box office | $44.2 million |

Amistad is a 1997 American historical drama film directed by Steven Spielberg, based on the events in 1839 aboard the Spanish slave ship La Amistad, during which Mende tribesmen abducted for the slave trade managed to gain control of their captors' ship off the coast of Cuba, and the international legal battle that followed their capture by the Washington, a U.S. revenue cutter. The case was ultimately resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841.

Morgan Freeman, Anthony Hopkins, Djimon Hounsou, and Matthew McConaughey had starring roles. David Franzoni's screenplay was based on the 1987 book Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy, by the historian Howard Jones.

The film received largely positive critical reviews and grossed over $44 million at the US box office.

Plot[]

La Amistad is a slave ship transporting captured Africans from Spanish Cuba to the United States in 1839. Joseph Cinqué, a leader of the Africans, leads a mutiny and takes over the ship. The mutineers spare the lives of two Spanish navigators to help them sail the ship back to Africa. Instead, the navigators misdirect the Africans and sail directly north to the east coast of the United States, where the ship is stopped by the American Navy, and the surviving Africans imprisoned as runaway slaves.

In an unfamiliar country and not speaking a single word of English, the Africans find themselves in a legal battle. United States Attorney William S. Holabird brings charges of piracy and murder. Secretary of State John Forsyth, on behalf of President Martin Van Buren (who is campaigning for re-election), represents the claim of the Spanish government[a] that the African captives are property of Spain based on a treaty. Two Naval officers, Thomas R. Gedney, and Richard W. Meade, claim them as salvage while the two Spanish navigators, Pedro Montez and Jose Ruiz, produce proof of purchase. A lawyer named Roger Sherman Baldwin, hired by the abolitionist Lewis Tappan and his black associate Theodore Joadson, decides to defend the Africans.

Baldwin argues that the Africans had been kidnapped from the British colony of Sierra Leone to be sold in the Americas illegally. Baldwin proves through documents found hidden aboard La Amistad that the African captives were initially cargo belonging to a Portuguese slave ship, the Tecora. Therefore, the Africans were free citizens of Sierra Leone and not slaves at all. In light of this evidence, the staff of President Van Buren has the judge presiding over the case replaced by Judge Coglin, who is younger and believed to be impressionable and easily influenced. Consequently, seeking to make the case more personal, on the advice of former American president (and lawyer) John Quincy Adams, Baldwin and Joadson find James Covey, a former slave who speaks both Mende and English. Cinqué tells his story at trial: Cinqué was kidnapped by slave traders outside his village, and held in the slave fortress of Lomboko, where thousands of captives were held under heavy guard. Cinqué and many others were then sold to the Tecora, where they were held in the brig of the ship. The captives were beaten and whipped, and at times, were given so little food that they had to eat the food from each other's faces. One day, fifty captives were thrown overboard. Later on, the ship arrived in Havana, Cuba. Those captives that were not sold at auction were handed over to La Amistad.

United States Attorney Holabird attacks Cinqué's "tale" of being captured and kept in the slave fortress, and especially questions the throwing of precious cargo overboard. Holabird contends that Cinqué could have been made a debt slave by his fellow Sierra Leoneans. However, the Royal Navy's fervent abolitionist Captain Fitzgerald of the West Africa Squadron backs up Cinqué's account. Baldwin shows from the Tecora’s inventory that the number of African people taken as slaves was reduced by fifty. Fitzgerald explains that some slave ships when interdicted do this to get rid of the evidence for their crime but in the Tecora’s case, they had underestimated the amount of provisions necessary for their journey. As the tension rises, Cinqué stands up from his seat and repeatedly says, "Give us, us free!"

Judge Coglin rules in favor of the Africans. After pressure from Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina on President Van Buren, the case is appealed to the Supreme Court. Despite refusing to help when the case was initially presented, Adams agrees to assist with the case. At the Supreme Court, he makes an impassioned and eloquent plea for their release, and is successful.

The Lomboko slave fortress is liberated by the Royal Marines under the command of Captain Fitzgerald. After all the slaves are removed from the fortress, Fitzgerald orders the ship's cannon to destroy it. He then dictates a letter to Forsyth saying that he was correct — the slave fortress does not exist.

Because of the release of the Africans, Van Buren loses his re-election campaign, and tension builds between the North and the South, which eventually culminates in the Civil War.

Cinqué eventually returns to his homeland, but never reunites with his family.

Cast[]

- Djimon Hounsou as Sengbe Pieh / Joseph Cinqué

- Matthew McConaughey as Roger Sherman Baldwin

- Anthony Hopkins as John Quincy Adams

- Morgan Freeman as Theodore Joadson

- Nigel Hawthorne as President Martin Van Buren

- David Paymer as Secretary of State John Forsyth

- Pete Postlethwaite as William S. Holabird

- Stellan Skarsgård as Lewis Tappan

- Razaaq Adoti as Yamba

- Abu Bakaar Fofanah as Fala

- Anna Paquin as Queen Isabella II of Spain

- Tomas Milian as Ángel Calderón de la Barca y Belgrano

- Chiwetel Ejiofor as Ensign James Covey

- Derrick Ashong as Buakei

- Geno Silva as Jose Ruiz

- John Ortiz as Pedro Montes

- Kevin J. O'Connor as Missionary

- Ralph Brown as Lieutenant Thomas R. Gedney

- Darren E. Burrows as Lieutenant Richard W. Meade

- Allan Rich as Judge Andrew T. Judson

- Paul Guilfoyle as Attorney

- Peter Firth as Captain Charles Fitzgerald

- Xander Berkeley as Ledger Hammond

- Jeremy Northam as Judge Coglin

- Arliss Howard as John C. Calhoun

- Austin Pendleton as Professor Josiah Willard Gibbs Sr.

- Pedro Armendáriz Jr. as General Baldomero Espartero

Retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun also appears in the film as Justice Joseph Story.

Casting[]

Cuba Gooding Jr. was offered the role of Joseph Cinqué but turned it down and later regretted it.[1][2]

Dustin Hoffman was offered a role but turned it down.[3]

Production[]

Music[]

| Amistad: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Film score by John Williams | ||||

| Released | December 9, 1997 | |||

| Recorded | 1997 | |||

| Studio | Sony Pictures Studios | |||

| Genre | Film score | |||

| Length | 55:51 | |||

| Label | DreamWorks | |||

| Producer | John Williams | |||

| John Williams chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Filmtracks | |

| Movie Wave | |

The musical score for Amistad was composed by John Williams. A soundtrack album was released on December 9, 1997 by DreamWorks Records.[4]

Historical accuracy[]

Many academics, including Columbia University professor Eric Foner, have criticized Amistad for historical inaccuracy and the misleading characterizations of the Amistad case as a "turning point" in the American perspective on slavery.[5] Foner wrote: "In fact, the Amistad case revolved around the Atlantic slave trade — by 1840 outlawed by international treaty — and had nothing whatsoever to do with slavery as a domestic institution. Incongruous as it may seem, it was perfectly possible in the nineteenth century to condemn the importation of slaves from Africa while simultaneously defending slavery and the flourishing slave trade within the United States... Amistad’s problems go far deeper than such anachronisms as President Martin Van Buren campaigning for re-election on a whistle-stop train tour (in 1840, candidates did not campaign), or people constantly talking about the impending Civil War, which lay 20 years in the future."[5] However, a counter this criticism is that President Van Buren did travel by train and give numerous speeches during the campaign of 1840[6] and that South Carolina's politicians did lead secession movements on numerous occasions during the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s such as the Nullification crisis[7] and the Bluffton Movement.[8] On those occasions John C. Calhoun was South Carolina's (and more broadly the south's) main spokesman in Washington DC, as reflected in the film.[9]

Other reported inaccuracies include:

- During the scene depicting the destruction of the Lomboko slave fortress by a Royal Navy schooner, the vessel's captain refers to another officer as "ensign". This rank has never been used by the Royal Navy.[10]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

Amistad received mainly positive reviews. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 77% based on reviews from 64 critics, with an average score of 6.9/10. Its consensus reads: "Heartfelt without resorting to preachiness, Amistad tells an important story with engaging sensitivity and absorbing skill."[11]

Susan Wloszczyna of USA Today summed up the feelings of many reviewers when she wrote: "as Spielberg vehicles go, Amistad — part mystery, action thriller, courtroom drama, even culture-clash comedy — lands between the disturbing lyricism of Schindler's List and the storybook artificiality of The Color Purple."[12] Roger Ebert awarded the film three out of four stars, writing:

"Amistad," like Spielberg's "Schindler's List," is [...] about the ways good men try to work realistically within an evil system to spare a few of its victims. [...] "Schindler's List" works better as narrative because it is about a risky deception, while "Amistad" is about the search for a truth that, if found, will be small consolation to the millions of existing slaves. As a result, the movie doesn't have the emotional charge of Spielberg's earlier film — or of "The Color Purple," which moved me to tears. [...] What is most valuable about "Amistad" is the way it provides faces and names for its African characters, whom the movies so often make into faceless victims.[13]

In 2014, the movie was one of several discussed by Noah Berlatsky in The Atlantic in an article concerning white savior narratives in film, calling it 'sanctimonious drivel.'[14]

Morgan Freeman is very proud of the movie: "I loved the film. I really did. I had a moment of err, during the killings. I thought that was a little over-wrought. But he (Spielberg) wanted to make a point and I understood that."[15]

Box office[]

The film debuted at No. 5 on December 10, 1997, and earned $44,229,441 at the box office in the United States.[16]

Awards and honors[]

Amistad was nominated for Academy Awards in four categories: Best Supporting Actor (Anthony Hopkins), Best Original Dramatic Score (John Williams), Best Cinematography (Janusz Kamiński), and Best Costume Design (Ruth E. Carter).[17]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award | Best Supporting Actor | Anthony Hopkins | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Ruth E. Carter | Nominated | |

| Best Original Dramatic Score | John Williams | Nominated | |

| American Society of Cinematographers | Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases | Janusz Kamiński | Nominated |

| Art Directors Guild | Excellence in Production Design for a Feature Film | Rick Carter (production designer), Tony Fanning, Christopher Burian-Mohr, William James Teegarden (art directors) Lauren Polizzi, John Berger, Paul Sonski (assistant art directors) Nicholas Lundy, Hugh Landwehr (new york art directors) |

Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association | Best Supporting Actor | Anthony Hopkins | Nominated |

| Most Promising Actor | Djimon Hounsou | Nominated | |

| Critics' Choice Movie Award | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Anthony Hopkins | Won | |

| David di Donatello | Best Foreign Film | Steven Spielberg | Nominated |

| Directors Guild of America Award | Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | Nominated | |

| European Film Awards | Achievement in World Cinema (also for Good Will Hunting) |

Stellan Skarsgård | Won |

| Golden Globe Award | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Djimon Hounsou | Nominated |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | |

| Best Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Anthony Hopkins | Nominated | |

| Grammy Award | Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television | John Williams | Nominated |

| NAACP Image Award | Outstanding Actor in a Motion Picture | Djimon Hounsou | Won |

| Outstanding Motion Picture | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Morgan Freeman | Won | |

| Online Film Critics Society | Best Supporting Actor | Anthony Hopkins | Nominated |

| Producers Guild of America Award | Best Theatrical Motion Picture | Steven Spielberg, Debbie Allen, Colin Wilson | Nominated |

| Political Film Society Awards | Exposé | Nominated | |

| Satellite Award | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Djimon Hounsou | Nominated |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | David Franzoni | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Rick Carter | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Ruth E. Carter | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn | Nominated | |

| Best Film – Drama | Steven Spielberg, Debbie Allen, Colin Wilson | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Nominated | |

| Screen Actors Guild Award | Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role | Anthony Hopkins | Nominated |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association | Best Supporting Actor | 2nd place | |

See also[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Queen Isabella II of Spain was the nominal head of the Spanish government, but at the time was ten years old and living in exile in Rome with her mother Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies while Spain was under the liberal regency of Baldomero Espartero and under the government of prime minister Antonio González, 1st Marquess of Valdeterrazo.

References[]

- ^ "Cuba Gooding Pinpoints Where It Might Have All Gone Wrong".

- ^ "Wow! Cuba Gooding, Jr. Turned Down Steven Spielberg | Larry King Now | Ora.TV".

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/dec/14/dustin-hoffman-interview-simon-hattenstone

- ^ "Amistad Soundtrack (John Williams)". Soundtrack.Net. Autotelics. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foner, Eric. "The Amistad Case in Fact and Film", History Matters. Accessed December 8, 2011.

- ^ Carnival Campaign: How the Rollicking 1840 Campaign of "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too" Changed Presidential Elections Forever by Ronald Shafer

- ^ The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States' Rights and the Nullification Crisis by Richard E. Ellis, Oxford University Press, 1989

- ^ Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1 by Junius P. Rodriguez, pg. 197

- ^ Calhoun: American Heretic by Robert Elder, pg. 16-29

- ^ "Officer Ranks in the Royal Navy". royalnavalmuseum.org. British Royal Navy ranks (including relevant time period). Royal Naval Museum. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Amistad Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan. "Amistad review", USA Today. Accessed December 8, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 12, 1997). "Amistad :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved Dec 8, 2011.

- ^ Berlatsky, Noah (January 17, 2014). "12 Years a Slave: Yet Another Oscar-Nominated 'White Savior' Story". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ "Morgan Freeman". 14 July 2000.

- ^ "Amistad". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ "Academy Awards: Amistad". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Amistad (film) |

- Amistad at IMDb

- Amistad at AllMovie

- Amistad at Box Office Mojo

- Amistad at Rotten Tomatoes

- Amistad at Virtual History

- 1997 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 1990s historical drama films

- 1990s legal films

- American historical drama films

- American legal drama films

- American courtroom films

- Military courtroom films

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- Films about American slavery

- Films about lawyers

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Films about presidents of the United States

- Cultural depictions of John Quincy Adams

- Films set in Connecticut

- Films set in Cuba

- Films set in Boston

- Films set in Massachusetts

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in Sierra Leone

- Films set in the 1830s

- Films set in 1839

- Films set in the 1840s

- Films set in 1840

- Films set in 1841

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Connecticut

- Films shot in Massachusetts

- Films shot in Rhode Island

- Films about race and ethnicity

- La Amistad

- Films scored by John Williams

- HBO Films films

- Mende-language films

- 1997 drama films

- Films set in the British Empire

- Films about interpreting and translation

- Films set in Spain

- Films about American politicians

- Films about diplomacy

- Cultural depictions of Isabella II of Spain

- Films set on ships