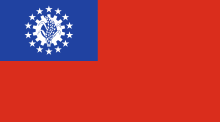

Ethnic nationalism in Myanmar

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (March 2021) |

Ethnic nationalism in Myanmar has a long and complex history and plays a critical role in the civil war the country has been experiencing since the 1940s.

History[]

Myanmar was regarded historically as one of the most powerful countries in Southeast Asia.[1]

Burmese nationalism initially aimed to overthrow British rule. The British divided ethnic minorities against the Bamar majority, often using ethnic minorities to dominate the Bamar people. Nationalism grew in British Burma.[2] As the British Empire began to retreat from Burma, the policy led to the ongoing internal conflict in Myanmar.[3][4]

Ethnic insurgencies[]

Karen people[]

The Karen people of Kayin State (formerly Karen State) in eastern Myanmar are the third largest ethnic group in Myanmar, consisting of roughly 7% of the country's total population. Karen insurgent groups have fought for independence and self-determination since 1949. In 1949, the commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw General Smith Dun, an ethnic Karen, was fired because of the rise of Karen opposition groups, which furthered ethnic tensions. He was replaced by Ne Win.[5]

The initial aim of the Karen National Union (KNU) and its armed wing the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) was to create independent state for the Karen people. However, since 1976 they have instead called for a federal union with fair Karen representation and the self-determination of the Karen people.[6]

In 1995, the main headquarters and operating bases of the KNU were mostly destroyed or captured by the government, forcing the KNLA to operate from the jungles of Kayin State. Until 1995, the Thai government supported insurgents across the Myanmar–Thailand border, but soon stopped its support due to a new major economic deal with Myanmar.

The KNU signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) with the government of Myanmar on 15 October 2015, along with seven other insurgent groups.[7] However, in March 2018, the government of Myanmar violated the agreement by sending 400 Tatmadaw soldiers into KNU-held territory to build a road connecting two military bases.[8] Armed clashes erupted between the KNU and the Myanmar Army in the Ler Mu Plaw area of Hpapun District, resulting in the displacement of 2,000 people.[9] On 17 May 2018, the Tatmadaw agreed to "temporarily postpone" their road project and to withdraw troops from the area.[10]

The KNU resumed its fight against the Myanmar government following the 2021 military coup. On 27 April 2021, KNU insurgents captured a military base on the west bank of the Salween River, which forms Myanmar's border with Thailand. The Tatmadaw later retaliated with airstrikes on KNU positions. Their were no casualties reported by either side.[11]

Mon people[]

The indigenous Mon people, who live in southern Burma, have a close linguistic relationship with the Vietnamese and Khmers; all three groups speak Austroasiatic languages. The Mons' relationship with the Bamars has fluctuated; they had fought to regain their independent Hanthawaddy Kingdom, who are culturally close but linguistically different. Siam often supported Mon insurrections against Burma as part of its buffer-zone policy.[12]

The Mon Hanthawaddy was finally conquered after the Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War.[13] The Mons sided with Britain after the British conquest.[14] The Mons eventually became hostile to the British administration, and later turned against the colonial government.[15]

Arakanese[]

On 4 January 2019, around 300 Arakan Army insurgents launched pre-dawn attacks on four border police outposts—Kyaung Taung, Nga Myin Taw, Ka Htee La and Kone Myint—in northern Buthidaung Township.[16] Thirteen members of the Border Guard Police (BGP) were killed and nine others were injured,[17][18][19] while 40 firearms and more than 10,000 rounds of ammunition were looted. The Arakan Army later stated that it had captured nine BGP personnel and five civilians, and that three of its fighters were also killed in the attacks.[20][21]

Following the attacks, the Office of the President of Myanmar held a high-level meeting on national security in the capital Naypyidaw on 7 January 2019, and instructed the Defense Ministry to increase troop deployments in the areas that were attacked and to use aircraft if necessary.[22] Subsequent clashes between the Myanmar Army and the Arakan Army were reported in Maungdaw, Buthidaung, Kyauktaw, Rathedaung and Ponnagyun Townships, forcing out over 5,000 civilians from their homes,[23][24] hundreds of whom (mostly Rakhine and Khami) have fled across the border into Bangladesh.[25]

Shans[]

The Shan State is one of Myanmar's most diversified regions. The Shan people are the most numerous and have strong ties to the other Tai peoples: the Thais and Laotians. The Shan people moved to Myanmar after the Mongol invasions of Burma, and remained there after forming an independent state.[26] Since the 16th-century rise of the Burmese Empire, its rulers barred settlers from taking Shan territory and left it alone; Bamar nationalists initially did not see the Shans as a threat. The Shans contributed troops to fight for the Burmese Empire, notably against the British during the Anglo-Burmese Wars.[26] The British acknowledged Shan independence, granting the region full autonomy as the Shan States and the later Federated Shan States. Shan nationalism did not develop separately, but became a force reinforcing Bamar nationalism. The Shans participated in the Panglong Agreement and became part of Burma. Aung San's assassination, however, ensured that the agreement was never honoured.[27]

Although the Shan people initially did not join the Burmese insurgency, Ne Win's 1962 coup d'état and the arrest of Sao Shwe Thaik sparked tensions between the Shans and the Burmese.[28][29]

Kokang[]

From the 1960s to 1989, the Kokang area in northern Shan state was controlled by the Communist Party of Burma, and after the party's armed wing disbanded in 1989 it became a special region of Myanmar under the control of the Myanmar Nationalities Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). The MNDAA is a Kokang insurgent group active in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in northern Shan State. The group signed a ceasefire agreement with the government in 1989, the same year it was founded, which lasted for two decades until 2009, when government troops entered MNDAA territory in an attempt to stop the flow of drugs through the area.[30] Violence erupted again in 2015, when the MNDAA attempted to retake territory it had lost in 2009.[31][32] The MNDAA clashed with government troops once again in 2017.[33][34]

Foreign support[]

China[]

The People's Republic of China has long been accused of having a multifaceted role in the conflict, given its close relations with both the Myanmar government and insurgent groups active along the China–Myanmar border.[35] China openly supported the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and its pursuit of Mao Zedong Thought during the 1960s and 1970s.[36][37] After the CPB's armed wing agreed to disarm in 1988, China was accused by Myanmar of continuing to support insurgent groups operating along its border, such as the United Wa State Army[38] and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, the latter enjoying closer ties to China due to a common Han Chinese ethnic background.[39]

In 2016, China pledged to support Myanmar's peace process by encouraging China-friendly insurgent groups to attend peace talks with the Burmese government and by sending more soldiers to secure its border with Myanmar. China also offered $3 million USD to fund the negotiations. However, the Burmese government has expressed suspicion over China's involvement in the peace process, due to China's alleged links to the Northern Alliance and the United Wa State Army.[40]

India[]

India and Myanmar share a strategic military relationship due to the overlapping insurgency in Northeast India. India has provided Myanmar's military with training, weapons, and tactical equipment.[41] The two countries' armies have conducted joint operations against insurgents at their border since the 1990s.[42] Myanmar has also taken an active role in finding and arresting insurgents that fled from northeast India; in May 2020 Myanmar handed over 22 insurgents, included several top commanders, to Indian authorities.[43] Similarly, India has been the only country to forcefully repatriate Rohingya refugees back to Myanmar despite global outcry.[44]

Pakistan[]

From 1948 to 1950, Pakistan sent aid to mujahideen in northern Arakan (present-day Rakhine State). In 1950, the Pakistani government warned their Burmese counterparts about their treatment of Muslims. In response, Burmese Prime Minister U Nu immediately sent a Muslim diplomat, Pe Khin, to negotiate a memorandum of understanding. Pakistan agreed to cease aid to the mujahideen and arrest members of the group. In 1954, mujahid leader Mir Kassem was arrested by Pakistani authorities, and many of his followers later surrendered to the Burmese government.[45]

The International Crisis Group reported on 14 December 2016 that in interviews with the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), its leaders claimed to have links to private donors in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The ICG also released unconfirmed reports that Rohingya villagers had been "secretly trained" by Afghan and Pakistani fighters.[46][47] In September 2017, Bangladeshi sources stated that the possibility of cooperation between Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and ARSA was "extremely high".[48]

Attempted mediation[]

Several insurgent groups have negotiated ceasefires and peace agreements with successive governments, which, until political reforms in the early 2010s, had largely fallen apart.[49]

Under the new constitutional reforms in 2011, state level and union level ceasefire agreements were made with several insurgent groups. 14 out of 17 of the largest rebel factions signed a ceasefire agreement with the new reformed government. All of the 14 signatories wanted negotiations in accordance with the Panglong Agreement of 1947, which granted self-determination, a federal system of government (meaning regional autonomy), religious freedom and ethnic minority rights. However, the new constitution, only had a few clauses dedicated to minority rights, and therefore, the government discussed with rebel factions using the new constitution for reference, rather than the Panglong Agreement. There was no inclusive plan or body that represented all the factions, and as a result, in resent, the KNU backed out of the conference and complained the lack of independence for each party within the ethnic bloc.[50] However, most of the negotiations between the State Peace Deal Commission and rebel factions were formal and peaceful.[51]

On 31 March 2015, a draft of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) was finalised between representatives from 15 different insurgent groups (all part of the Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team or NCCT) and the government of Myanmar.[52] However, only eight of the 15 insurgent groups signed the final agreement on 15 October 2015.[53] The signing was witnessed by observers and delegates from the United Nations, the United Kingdom, Norway, Japan and the United States.[54][55] Two other insurgent groups later joined the agreement on 13 February 2018.[56][57][58][59]

The Union Peace Conference - 21st Century Panglong was held from 31 August to 4 September 2016 with several different organisations as representatives, in an attempt to mediate between the government and different insurgent groups. Talks ended without any agreement being reached.[60] The name of the conference was a reference to the original Panglong Conference held during British rule in 1947, which was negotiated between Aung San and ethnic leaders.[61]

References[]

- ^ "Myanmar - The emergence of nationalism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Religion, Ethnicity, and Nationalism in Burma". www.researchgate.net. 2016. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-25. Retrieved 2020-08-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "An Overview of Burma's Ethnic Politics". www.culturalsurvival.org.

- ^ Smith, Martin (1991). Burma: Insurgency and the politics of ethnicity (2. impr. ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 0862328683.

- ^ "About". Karen National Union. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Myanmar Signs Historic Cease-Fire Deal With Eight Ethnic Armies". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Sandford, Steve (31 May 2018). "Conflict Resumes in Karen State After Myanmar Army Returns". Voice of America. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Sandford, Steve (31 May 2018). "Karen Return to War in Myanmar". Voice of America. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Nyein, Nyein (17 May 2018). "Tatmadaw Agrees to Halt Contentious Road Project in Karen State". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "Fighting erupts in Myanmar; junta to 'consider' ASEAN plan". Reuters. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "SMALL KINGDOMS AFTER PAGAN: AVA (INWA), PEGU (BAGO), THE SHAN STATES AND ARAKAN | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com.

- ^ Yi, Ma Yi (March 1, 1965). "Burmese Sources for the History of the Konbaung Period 1752–1885*". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 6 (1): 48–66. doi:10.1017/S0217781100002477 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Chulalongkorn University Mon Seminar" (PDF). www.ashleysouth.co.uk. 2007. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ "Ethnic Conflict and Social Services in Myanmar's Contested Regions" (PDF). asiafoundation.org. 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (3 January 2019). "Arakan Army clashes with government forces in Rakhine state". Asia Times. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "13 policemen die in Rakhine rebel attacks". The Straits Times. 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Aung, Min Thein (4 January 2019). "Rakhine Insurgents Kill 13 Policemen, Injure Nine Others in Myanmar Outpost Attacks". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Aung, Thu Thu; Naing, Shoon (4 January 2019). "Rakhine Buddhist rebels kill 13 in Independence Day attack on..." Reuters. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Emont, Jon; Myo, Myo (4 January 2019). "Buddhist Violence Portends New Threat to Myanmar". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "AA Frees 14 Police, 4 Women Captured in Attack on Border Posts". The Irrawaddy. 5 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "President Convenes Top-Level Security Meeting in Wake of AA Attacks". The Irrawaddy. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "UN Calls for 'Rapid and Unimpeded' Aid Access to Myanmar's Rakhine". The Irrawaddy. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Myanmar villagers flee to Bangladesh amid Rakhine violence". Al Jazeera. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "203 Buddhists from Rakhine entered Bangladesh in last 5 days". Dhaka Tribune. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (March 1984). "The Shans and the Shan State of Burma". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 5 (4): 403–450. doi:10.1355/CS5-4B. JSTOR 25797781.

- ^ Donald M. Seekins (2006). Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 410–411. ISBN 9780810854765.

- ^ "UNPO: Shan-Burmese Relation: Historical Account and Contemporary Politics". unpo.org.

- ^ Johnston, Tim (29 August 2009). "China Urges Burma to Bridle Ethnic Militia Uprising at Border". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Myanmar Kokang Rebels Deny Receiving Chinese Weapons". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ NANG MYA NADI (10 February 2015). "Kokang enlist allies' help in fight against Burma army". dvb.no. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Deadly clashes hit Kokang in Myanmar's Shan state". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Myanmar rebel clashes in Kokang leave 30 dead". BBC News. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "China's Role in Myanmar's Internal Conflicts". United States Institute of Peace. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Fan, Hongwei (1 June 2012). "The 1967 Anti-Chinese Riots in Burma and Sino-Burmese Relations". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 43 (2): 234–256. doi:10.1017/S0022463412000045.

- ^ Smith, Martin (1991). Burma: Insurgency and the politics of ethnicity (2. impr. ed.). London and New Jersey: Zed Books. ISBN 0862328683.[page needed]

- ^ "UCDP Conflict Encyclopedia, Myanmar (Burma)". Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "The MNDAA: Myanmar's crowdfunding ethnic insurgent group". Reuters. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Vrieze, Paul. "Into Myanmar's Stalled Peace Process Steps China". VOA. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Thiha, Amara (25 August 2017). "The Bumpy Relationship Between India and Myanmar". The Diplomat. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Kanwal, Gurmeet (8 June 2015). "Manipur ambush: Why Army [sic?] saw the worst attack in 20 years". DailyO. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar Army hands over 22 'Most Wanted Militants' from Northeast India, including top UNLF and NDFB commanders". Northeast Now News. 15 May 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Kinseth, Ashley Starr (28 January 2019). "India's Rohingya shame". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ U Nu, U Nu: Saturday's Son, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) 1975, p. 272.

- ^ J, Jacob (15 December 2016). "Rohingya militants in Rakhine have Saudi, Pakistan links, think tank says". Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Rohingya insurgency a 'game-changer' for Myanmar". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Sudhi Ranjan Sen. "As Rohingya deepens, Bangladesh fears Pakistan's ISI will foment trouble". India Today.

- ^ Licklider, R. (1995). The Consequences of Negotiated Settlements in Civil Wars, 1945–1993. The American Political Science Review, 89(3), 681.

- ^ Nai, A. (3 September 2014). Democratic Voice of Burma: UNFC opens 2 top positions for KNU. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "World Asia". BBC News. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Heijmans, Philip. "Myanmar government and rebels agree on ceasefire draft". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Myanmar Signs Historic Cease-Fire Deal With Eight Ethnic Armies". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Asia Unbound » Myanmar's Cease-Fire Deal Comes up Short". Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Ray Pagnucco and Jennifer Peters (15 October 2015). "Myanmar's National Ceasefire Agreement isn't all that national". Vice News. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ "2 groups join Myanmar government's peace process". AP News. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "New Mon State Party and Lahu Democratic Union sign NCA". Office of the President of Myanmar. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Analysis: A Win for Peace Commission as Mon, Lahu Groups Sign NCA". The Irrawaddy. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "NCA signing ceremony for NMSP, LDU to take place on 13 Feb". Mizzima. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Giry, Stéphanie; Moe, Wai (3 September 2016). "Myanmar Peace Talks End With No Breakthrough but Some Hope". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar's Panglong Peace Conference to Include All Armed Ethnic Groups". Radio Free Asia.

- Ethnic nationalism

- Burmese nationalism

- Political history of Myanmar