CDH1 (gene)

| CDH1 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||

| Aliases | CDH1, Arc-1, CD324, CDHE, ECAD, LCAM, UVO, cadherin 1, BCDS1 | ||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 192090 MGI: 88354 HomoloGene: 20917 GeneCards: CDH1 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||

| Entrez | |||||||||||||

| Ensembl | |||||||||||||

| UniProt | |||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||||||

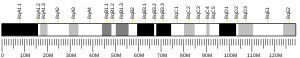

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 16: 68.74 – 68.84 Mb | Chr 8: 106.6 – 106.67 Mb | |||||||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Cadherin-1 (not to be confused with the APC/C activator protein CDH1) also known as CAM 120/80 or epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) or uvomorulin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CDH1 gene.[5] Mutations are correlated with gastric, breast, colorectal, thyroid, and ovarian cancers. CDH1 has also been designated as CD324 (cluster of differentiation 324). It is a tumor suppressor gene.[6][7]

Function[]

Cadherin-1 is a classical member of the cadherin superfamily. The encoded protein is a calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesion glycoprotein composed of five extracellular cadherin repeats, a transmembrane region, and a highly conserved cytoplasmic tail. Mutations in this gene are correlated with gastric, breast, colorectal, thyroid, and ovarian cancers. Loss of function is thought to contribute to progression in cancer by increasing proliferation, invasion, and/or metastasis. The ectodomain of this protein mediates bacterial adhesion to mammalian cells, and the cytoplasmic domain is required for internalization. Identified transcript variants arise from mutation at consensus splice sites.[8]

E-cadherin (epithelial) is the most well-studied member of the cadherin family. It consists of 5 cadherin repeats (EC1 ~ EC5) in the extracellular domain, one transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain that binds p120-catenin and beta-catenin. The intracellular domain contains a highly-phosphorylated region vital to beta-catenin binding and, therefore, to E-cadherin function.[citation needed] Beta-catenin can also bind to alpha-catenin. Alpha-catenin participates in regulation of actin-containing cytoskeletal filaments. In epithelial cells, E-cadherin-containing cell-to-cell junctions are often adjacent to actin-containing filaments of the cytoskeleton.

E-cadherin is first expressed in the 2-cell stage of mammalian development, and becomes phosphorylated by the 8-cell stage, where it causes compaction.[citation needed] In adult tissues, E-cadherin is expressed in epithelial tissues, where it is constantly regenerated with a 5-hour half-life on the cell surface.[citation needed] Cell–cell interactions mediated by E-cadherin are crucial to blastula formation in many animals.[9]

Clinical significance[]

Loss of E-cadherin function or expression has been implicated in cancer progression and metastasis.[10][11] E-cadherin downregulation decreases the strength of cellular adhesion within a tissue, resulting in an increase in cellular motility. This in turn may allow cancer cells to cross the basement membrane and invade surrounding tissues.[11] E-cadherin is also used by pathologists to diagnose different kinds of breast cancer. When compared with invasive ductal carcinoma, E-cadherin expression is markedly reduced or absent in the great majority of invasive lobular carcinomas when studied by immunohistochemistry.[12]

Interactions[]

CDH1 (gene) has been shown to interact with

Cancer[]

Metastasis[]

Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states play important roles in embryonic development and cancer metastasis. E-cadherin level changes in EMT (epithelial-mesenchymal transition) and MET (mesenchymal-epithelial transition). E-cadherin acts as an invasion suppressor and a classical tumor suppressor gene in pre-invasive lobular breast carcinoma.[40]

EMT[]

E-cadherin is a crucial type of cell–cell adhesion to hold the epithelial cells tight together. E-cadherin can sequester β-catenin on the cell membrane by the cytoplasmic tail of E-cadherin. Loss of E-cadherin expression results in releasing β-catenin into the cytoplasm. Liberated β-catenin molecules may migrate into the nucleus and trigger the expression of EMT-inducing transcription factors. Together with other mechanisms, such as constitutive RTK activation, E-cadherin loss can lead cancer cells to the mesenchymal state and undergo metastasis. E-cadherin is an important switch in EMT.[40]

MET[]

The mesenchymal state cancer cells migrate to new sites and may undergo METs in certain favorable microenvironment. For example, the cancer cells can recognize differentiated epithelial cell features in the new sites and upregulate E-cadherin expression. Those cancer cells can form cell–cell adhesions again and return to an epithelial state.[40]

Examples[]

- Inherited inactivating mutations in CDH1 are associated with Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer. Individuals with this condition have up to a 70% lifetime risk of developing diffuse gastric carcinoma, and females with CDH1 mutations have up to a 60% lifetime risk of developing lobular breast cancer.[41]

- Inactivation of CDH1 (accompany with loss of the wild-type allele) in 56% of lobular breast carcinomas.[42][43]

- Inactivation of CDH1 in 50% of diffuse gastric carcinomas.[44]

- Complete loss of E-cadherin protein expression in 84% of lobular breast carcinomas.[45]

Genetic and epigenetic control[]

Several proteins such as SNAI1/SNAIL,[46][47] ZFHX1B/SIP1,[48] SNAI2/SLUG,[49][50] TWIST1[51] and DeltaEF1[52] have been found to downregulate E-cadherin expression. When expression of those transcription factors is altered, transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin were overexpressed in tumor cells.[46][47][48][49][51][52] Another group of genes, such as AML1, p300 and HNF3,[53] can upregulate the expression of E-cadherin.[54]

In order to study the epigenetic regulation of E-cadherin, M Lombaerts et al. performed a genome wide expression study on 27 human mammary cell lines. Their results revealed two main clusters that have the fibroblastic or epithelial phenotype, respectively. In close examination, the clusters showing fibroblast phenotypes only have either partial or complete CDH1 promoter methylation, while the clusters with epithelial phenotypes have both wild-type cell lines and cell lines with mutant CDH1 status. The authors also found that EMT can happen in breast cancer cell lines with hypermethylation of CDH1 promoter, but in breast cancer cell lines with a CDH1 mutational inactivation EMT cannot happen. It contradicts the hypothesis that E-cadherin loss is the initial or primary cause for EMT. In conclusion, the results suggest that “E-cadherin transcriptional inactivation is an epi-phenomenon and part of an entire program, with much more severe effects than loss of E-cadherin expression alone”.[54]

Other studies also show that epigenetic regulation of E-cadherin expression occurs during metastasis. The methylation patterns of the E-cadherin 5’ CpG island are not stable. During metastatic progression of many cases of epithelial tumors, a transient loss of E-cadherin is seen and the heterogeneous loss of E-cadherin expression results from a heterogeneous pattern of promoter region methylation of E-cadherin.[55]

See also[]

- Hereditary lobular breast cancer

- Cluster of differentiation

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000039068 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Jump up to: a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000000303 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Huntsman DG, Caldas C (Mar 1999). "Assignment1 of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1) to chromosome 16q22.1 by radiation hybrid mapping". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 83 (1–2): 82–3. doi:10.1159/000015134. PMID 9925936. S2CID 39971762.

- ^ Semb H, Christofori G (December 1998). "The tumor-suppressor function of E-cadherin". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1588–93. doi:10.1086/302173. PMC 1377629. PMID 9837810.

- ^ Wong AS, Gumbiner BM (June 2003). "Adhesion-independent mechanism for suppression of tumor cell invasion by E-cadherin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 161 (6): 1191–203. doi:10.1083/jcb.200212033. PMC 2173007. PMID 12810698.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: CDH1 cadherin 1, type 1, E-cadherin (epithelial)".

- ^ Fleming TP, Papenbrock T, Fesenko I, Hausen P, Sheth B (August 2000). "Assembly of tight junctions during early vertebrate development". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 11 (4): 291–9. doi:10.1006/scdb.2000.0179. PMID 10966863.

- ^ Beavon IR (August 2000). "The E-cadherin-catenin complex in tumour metastasis: structure, function and regulation". European Journal of Cancer. 36 (13 Spec No): 1607–20. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00158-1. PMID 10959047.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weinberg, Robert (2006). The Biology of Cancer. Garland Science. pp. 864 pages. ISBN 9780815340782. Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ Rosen, P. Rosen's Breast Pathology, 3rd ed, 2009, p. 704. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ Fujita Y, Krause G, Scheffner M, Zechner D, Leddy HE, Behrens J, Sommer T, Birchmeier W (March 2002). "Hakai, a c-Cbl-like protein, ubiquitinates and induces endocytosis of the E-cadherin complex". Nature Cell Biology. 4 (3): 222–31. doi:10.1038/ncb758. PMID 11836526. S2CID 40423770.

- ^ Vodermaier HC, Gieffers C, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Peters JM (September 2003). "TPR subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex mediate binding to the activator protein CDH1". Current Biology. 13 (17): 1459–68. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00581-5. PMID 12956947. S2CID 5942532.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kang JS, Feinleib JL, Knox S, Ketteringham MA, Krauss RS (April 2003). "Promyogenic members of the Ig and cadherin families associate to positively regulate differentiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (7): 3989–94. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.3989K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0736565100. PMC 153035. PMID 12634428.

- ^ Klingelhöfer J, Troyanovsky RB, Laur OY, Troyanovsky S (August 2000). "Amino-terminal domain of classic cadherins determines the specificity of the adhesive interactions". Journal of Cell Science. 113 (16): 2829–36. doi:10.1242/jcs.113.16.2829. PMID 10910767.

- ^ Davies G, Jiang WG, Mason MD (April 2001). "HGF/SF modifies the interaction between its receptor c-Met, and the E-cadherin/catenin complex in prostate cancer cells". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 7 (4): 385–8. doi:10.3892/ijmm.7.4.385. PMID 11254878.

- ^ Daniel JM, Reynolds AB (September 1995). "The tyrosine kinase substrate p120cas binds directly to E-cadherin but not to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein or alpha-catenin". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 15 (9): 4819–24. doi:10.1128/mcb.15.9.4819. PMC 230726. PMID 7651399.

- ^ Ireton RC, Davis MA, van Hengel J, Mariner DJ, Barnes K, Thoreson MA, et al. (November 2002). "A novel role for p120 catenin in E-cadherin function". The Journal of Cell Biology. 159 (3): 465–76. doi:10.1083/jcb.200205115. PMC 2173073. PMID 12427869.

- ^ Bonné S, Gilbert B, Hatzfeld M, Chen X, Green KJ, van Roy F (April 2003). "Defining desmosomal plakophilin-3 interactions". The Journal of Cell Biology. 161 (2): 403–16. doi:10.1083/jcb.200303036. PMC 2172904. PMID 12707304.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hazan RB, Norton L (April 1998). "The epidermal growth factor receptor modulates the interaction of E-cadherin with the actin cytoskeleton". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (15): 9078–84. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.15.9078. PMID 9535896.

- ^ Kucerová D, Sloncová E, Tuhácková Z, Vojtechová M, Sovová V (December 2001). "Expression and interaction of different catenins in colorectal carcinoma cells". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 8 (6): 695–8. doi:10.3892/ijmm.8.6.695. PMID 11712088.

- ^ Oyama T, Kanai Y, Ochiai A, Akimoto S, Oda T, Yanagihara K, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Shibamoto S, Ito F (December 1994). "A truncated beta-catenin disrupts the interaction between E-cadherin and alpha-catenin: a cause of loss of intercellular adhesiveness in human cancer cell lines". Cancer Research. 54 (23): 6282–7. PMID 7954478.

- ^ Takahashi K, Suzuki K, Tsukatani Y (July 1997). "Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation and association of beta-catenin with EGF receptor upon tryptic digestion of quiescent cells at confluence". Oncogene. 15 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201160. PMID 9233779.

- ^ Kinch MS, Clark GJ, Der CJ, Burridge K (July 1995). "Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the adhesions of ras-transformed breast epithelia". The Journal of Cell Biology. 130 (2): 461–71. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.2.461. PMC 2199929. PMID 7542250.

- ^ Navarro P, Lozano E, Cano A (August 1993). "Expression of E- or P-cadherin is not sufficient to modify the morphology and the tumorigenic behavior of murine spindle carcinoma cells. Possible involvement of plakoglobin". Journal of Cell Science. 105 (4): 923–34. doi:10.1242/jcs.105.4.923. hdl:10261/78716. PMID 8227214.

- ^ Schmeiser K, Grand RJ (April 1999). "The fate of E- and P-cadherin during the early stages of apoptosis". Cell Death and Differentiation. 6 (4): 377–86. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4400504. PMID 10381631.

- ^ Laoukili J, Alvarez-Fernandez M, Stahl M, Medema RH (September 2008). "FoxM1 is degraded at mitotic exit in a Cdh1-dependent manner". Cell Cycle. 7 (17): 2720–6. doi:10.4161/cc.7.17.6580. PMID 18758239.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yoon YM, Baek KH, Jeong SJ, Shin HJ, Ha GH, Jeon AH, Hwang SG, Chun JS, Lee CW (September 2004). "WD repeat-containing mitotic checkpoint proteins act as transcriptional repressors during interphase". FEBS Letters. 575 (1–3): 23–9. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.089. PMID 15388328. S2CID 21762011.

- ^ Li Z, Kim SH, Higgins JM, Brenner MB, Sacks DB (December 1999). "IQGAP1 and calmodulin modulate E-cadherin function". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (53): 37885–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37885. PMID 10608854.

- ^ Piedra J, Miravet S, Castaño J, Pálmer HG, Heisterkamp N, García de Herreros A, Duñach M (April 2003). "p120 Catenin-associated Fer and Fyn tyrosine kinases regulate beta-catenin Tyr-142 phosphorylation and beta-catenin-alpha-catenin Interaction". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (7): 2287–97. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.7.2287-2297.2003. PMC 150740. PMID 12640114.

- ^ Nourry C, Maksumova L, Pang M, Liu X, Wang T (May 2004). "Direct interaction between Smad3, APC10, CDH1 and HEF1 in proteasomal degradation of HEF1". BMC Cell Biology. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-5-20. PMC 420458. PMID 15144564.

- ^ Shibata T, Gotoh M, Ochiai A, Hirohashi S (August 1994). "Association of plakoglobin with APC, a tumor suppressor gene product, and its regulation by tyrosine phosphorylation". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 203 (1): 519–22. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1994.2213. PMID 8074697.

- ^ Hinck L, Näthke IS, Papkoff J, Nelson WJ (June 1994). "Dynamics of cadherin/catenin complex formation: novel protein interactions and pathways of complex assembly". The Journal of Cell Biology. 125 (6): 1327–40. doi:10.1083/jcb.125.6.1327. PMC 2290923. PMID 8207061.

- ^ Knudsen KA, Wheelock MJ (August 1992). "Plakoglobin, or an 83-kD homologue distinct from beta-catenin, interacts with E-cadherin and N-cadherin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 118 (3): 671–9. doi:10.1083/jcb.118.3.671. PMC 2289540. PMID 1639850.

- ^ Hazan RB, Kang L, Roe S, Borgen PI, Rimm DL (December 1997). "Vinculin is associated with the E-cadherin adhesion complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (51): 32448–53. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.51.32448. PMID 9405455.

- ^ Brady-Kalnay SM, Rimm DL, Tonks NK (August 1995). "Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPmu associates with cadherins and catenins in vivo". The Journal of Cell Biology. 130 (4): 977–86. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.4.977. PMC 2199947. PMID 7642713.

- ^ Brady-Kalnay SM, Mourton T, Nixon JP, Pietz GE, Kinch M, Chen H, Brackenbury R, Rimm DL, Del Vecchio RL, Tonks NK (April 1998). "Dynamic interaction of PTPmu with multiple cadherins in vivo". The Journal of Cell Biology. 141 (1): 287–96. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.1.287. PMC 2132733. PMID 9531566.

- ^ Besco JA, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Frostholm A, Rotter A (October 2006). "Intracellular substrates of brain-enriched receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase rho (RPTPrho/PTPRT)". Brain Research. 1116 (1): 50–7. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.122. PMID 16973135. S2CID 23343123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Polyak K, Weinberg RA (April 2009). "Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 9 (4): 265–73. doi:10.1038/nrc2620. PMID 19262571. S2CID 3336730.

- ^ van der Post RS, Vogelaar IP, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Huntsman D, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. (June 2015). "Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical guidelines with an emphasis on germline CDH1 mutation carriers". Journal of Medical Genetics. 52 (6): 361–74. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103094. PMC 4453626. PMID 25979631.

- ^ Berx G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Nollet F, de Leeuw WJ, van de Vijver M, Cornelisse C, van Roy F (December 1995). "E-cadherin is a tumour/invasion suppressor gene mutated in human lobular breast cancers". The EMBO Journal. 14 (24): 6107–15. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00301.x. PMC 394735. PMID 8557030.

- ^ Berx G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Strumane K, de Leeuw WJ, Nollet F, van Roy F, Cornelisse C (November 1996). "E-cadherin is inactivated in a majority of invasive human lobular breast cancers by truncation mutations throughout its extracellular domain". Oncogene. 13 (9): 1919–25. PMID 8934538.

- ^ Becker KF, Atkinson MJ, Reich U, Becker I, Nekarda H, Siewert JR, Höfler H (July 1994). "E-cadherin gene mutations provide clues to diffuse type gastric carcinomas". Cancer Research. 54 (14): 3845–52. PMID 8033105.

- ^ De Leeuw WJ, Berx G, Vos CB, Peterse JL, Van de Vijver MJ, Litvinov S, et al. (December 1997). "Simultaneous loss of E-cadherin and catenins in invasive lobular breast cancer and lobular carcinoma in situ". The Journal of Pathology. 183 (4): 404–11. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199712)183:4<404::AID-PATH1148>3.0.CO;2-9. PMID 9496256.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, García De Herreros A (February 2000). "The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (2): 84–9. doi:10.1038/35000034. PMID 10655587. S2CID 23809509.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA (February 2000). "The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (2): 76–83. doi:10.1038/35000025. hdl:10261/32314. PMID 10655586. S2CID 28329186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, et al. (June 2001). "The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion". Molecular Cell. 7 (6): 1267–78. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00260-X. PMID 11430829.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hajra KM, Chen DY, Fearon ER (March 2002). "The SLUG zinc-finger protein represses E-cadherin in breast cancer". Cancer Research. 62 (6): 1613–8. PMID 11912130.

- ^ De Craene B, Gilbert B, Stove C, Bruyneel E, van Roy F, Berx G (July 2005). "The transcription factor snail induces tumor cell invasion through modulation of the epithelial cell differentiation program". Cancer Research. 65 (14): 6237–44. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3545. PMID 16024625.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA (June 2004). "Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis". Cell. 117 (7): 927–39. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. PMID 15210113. S2CID 16181905.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eger A, Aigner K, Sonderegger S, Dampier B, Oehler S, Schreiber M, Berx G, Cano A, Beug H, Foisner R (March 2005). "DeltaEF1 is a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin and regulates epithelial plasticity in breast cancer cells". Oncogene. 24 (14): 2375–85. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208429. PMID 15674322.

- ^ Liu YN, Lee WW, Wang CY, Chao TH, Chen Y, Chen JH (December 2005). "Regulatory mechanisms controlling human E-cadherin gene expression". Oncogene. 24 (56): 8277–90. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208991. PMID 16116478.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lombaerts M, van Wezel T, Philippo K, Dierssen JW, Zimmerman RM, Oosting J, van Eijk R, Eilers PH, van de Water B, Cornelisse CJ, Cleton-Jansen AM (March 2006). "E-cadherin transcriptional downregulation by promoter methylation but not mutation is related to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cell lines". British Journal of Cancer. 94 (5): 661–71. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602996. PMC 2361216. PMID 16495925.

- ^ Graff JR, Gabrielson E, Fujii H, Baylin SB, Herman JG (January 2000). "Methylation patterns of the E-cadherin 5' CpG island are unstable and reflect the dynamic, heterogeneous loss of E-cadherin expression during metastatic progression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (4): 2727–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.4.2727. PMID 10644736.

Further reading[]

- Berx G, Becker KF, Höfler H, van Roy F (1998). "Mutations of the human E-cadherin (CDH1) gene". Human Mutation. 12 (4): 226–37. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:4<226::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-D. PMID 9744472.

- Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WN, Pignatelli M (August 2000). "E-cadherin-catenin cell–cell adhesion complex and human cancer". The British Journal of Surgery. 87 (8): 992–1005. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01513.x. hdl:1765/56571. PMID 10931041. S2CID 3083613.

- Beavon IR (August 2000). "The E-cadherin-catenin complex in tumour metastasis: structure, function and regulation". European Journal of Cancer. 36 (13 Spec No): 1607–20. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00158-1. PMID 10959047.

- Wilson PD (April 2001). "Polycystin: new aspects of structure, function, and regulation". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (4): 834–45. doi:10.1681/ASN.V124834. PMID 11274246.

- Chun YS, Lindor NM, Smyrk TC, Petersen BT, Burgart LJ, Guilford PJ, Donohue JH (July 2001). "Germline E-cadherin gene mutations: is prophylactic total gastrectomy indicated?". Cancer. 92 (1): 181–7. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<181::AID-CNCR1307>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID 11443625.

- Hazan RB, Qiao R, Keren R, Badano I, Suyama K (April 2004). "Cadherin switch in tumor progression". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1014 (1): 155–63. Bibcode:2004NYASA1014..155H. doi:10.1196/annals.1294.016. PMID 15153430. S2CID 37486403.

- Bryant DM, Stow JL (August 2004). "The ins and outs of E-cadherin trafficking". Trends in Cell Biology. 14 (8): 427–34. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.007. PMID 15308209.

- Wang HD, Ren J, Zhang L (November 2004). "CDH1 germline mutation in hereditary gastric carcinoma". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 10 (21): 3088–93. doi:10.3748/wjg.v10.i21.3088. PMC 4611247. PMID 15457549.

- Reynolds AB, Carnahan RH (December 2004). "Regulation of cadherin stability and turnover by p120ctn: implications in disease and cancer". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 15 (6): 657–63. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.09.003. PMID 15561585.

- Moran CJ, Joyce M, McAnena OJ (April 2005). "CDH1 associated gastric cancer: a report of a family and review of the literature". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 31 (3): 259–64. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2004.12.010. PMID 15780560.

- Georgolios A, Batistatou A, Manolopoulos L, Charalabopoulos K (March 2006). "Role and expression patterns of E-cadherin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 25 (1): 5–14. PMID 16761612.

- Renaud-Young M, Gallin WJ (October 2002). "In the first extracellular domain of E-cadherin, heterophilic interactions, but not the conserved His-Ala-Val motif, are required for adhesion". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (42): 39609–16. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201256200. PMID 12154084.

External links[]

- CDH1+protein,+human at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer

- Human CDH1 genome location and CDH1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

- Genes on human chromosome 16

- Clusters of differentiation

- Tumor suppressor genes