CDKL5

CDKL5 is a gene that provides instructions for making a protein called cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 also known as serine/threonine kinase 9 (STK9) that is essential for normal brain development. Mutations in the gene can cause deficiencies in the protein. The gene regulates neuronal morphology through cytoplasmic signaling and controlling gene expression.[5] The CDKL5 protein acts as a kinase, which is an enzyme that changes the activity of other proteins by adding a cluster of oxygen and phosphorus atoms (a phosphate group) at specific positions. Researchers are currently working to determine which proteins are targeted by the CDKL5 protein.[6]

Mutations[]

Mutations in the CDKL5 gene cause CDKL5 deficiency disorder.[7] CDKL5 Deficiency had been thought of as a variant of Rett's Syndrome due to some similarities in the clinical presentation,[8] but it is now known to be an independent clinical entity caused by mutations in a distinct X-linked gene, and is considered separate from Rett Syndrome rather than a variant of it.[9] While CDKL5 is primarily associated with girls, it has been seen in boys as well.[10] This disorder includes many of the features of classic Rett syndrome (including developmental problems, loss of language skills, and repeated hand wringing or hand washing movements), but also causes recurrent seizures beginning in infancy. Some CDKL5 mutations change a single protein building block (amino acid) in a region of the CDKL5 protein that is critical for its kinase function. Other mutations lead to the production of an abnormally short, nonfunctional version of the protein. At least 50 disease-causing mutations in this gene have been discovered.[11]

Further confirmation that CDKL5 is an independent disorder with its own characteristics is provided by this study, published in April 2016, which concluded 'There were differences in the presentation of clinical features occurring in the CDKL5 disorder and in Rett syndrome, reinforcing the concept that CDKL5 is an independent disorder with its own distinctive characteristics'.[12] At one time, mutations in the CDKL5 gene were said to cause a disorder called (ISSX)[13][14] or West syndrome.[15][16] but this research established CDKL5 disorder as a distinct clinical entity.

Animal studies[]

GSK3β inhibitors in Cdkl5 knockout (Cdkl5 -/Y) mice rescues hippocampal development and learning.[17] Likewise, IGF-1 treatment in CDKL5 null mice restores synaptic deficits.[18]

Therapeutics[]

There are currently no approved drugs to treat CDKL5 Deficiency, save for Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs) to treat the epileptic seizures. These have limited efficacy, pointing to a strong need to develop new treatment strategies for patients.[19] Some treatments might show efficacy in a relevant proportion of patients, such as valproic acid, vigabatrin, clobazam or sodium channel blockers, as well as ketogenic diet.[20][unreliable medical source]

A clinical trial of Ataluren for nonsense mutations in CDKL5 and Dravet Syndrome has been announced.[21] This same drug was approved by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for use in treating nonsense mutations in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[22] This drug did not show any efficacy in patients with CDKL5 mutations. Finally a CDKL5 protein replacement therapy is in development.[23]

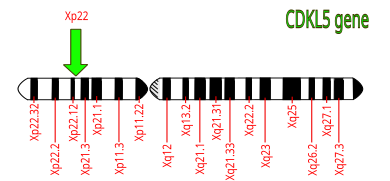

Location[]

The CDKL5 gene is located on the short (p) arm of the X chromosome at position 22.[24] More precisely, the CDKL5 gene is located from base pair 18,443,724 to base pair 18,671,748 on the X chromosome.[6]

ICD-10[]

G40.42

See also[]

- Cyclin-dependent kinase

- Rett syndrome

- West syndrome

- CDKL5 deficiency disorder

References[]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000008086 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031292 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Rusconi L, La Montanara P, Ciceri D, Bergo A, Bedogni F, Landsberger N (2012). "What we know and would like to know about CDKL5 and its involvement in epileptic encephalopathy". (secondary). Neural Plasticity. 2012: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2012/728267. PMC 3385648. PMID 22779007.

- ^ a b CDKL5 on Genetics Home Reference

- ^ "CDKL5 deficiency disorder". Medlineplus. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Weaving LS, Ellaway CJ, Gécz J, Christodoulou J (January 2005). "Rett syndrome: clinical review and genetic update". (secondary). Journal of Medical Genetics. 42 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.027730. PMC 1735910. PMID 15635068.

- ^ Fehr S, Wilson M, Downs J, Williams S, Murgia A, Sartori S, Vecchi M, Ho G, Polli R, Psoni S, Bao X, de Klerk N, Leonard H, Christodoulou J (March 2013). "The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy". (primary). European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (3): 266–73. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.156. PMC 3573195. PMID 22872100.

- ^ Wong VC, Kwong AK (April 2015). "CDKL5 variant in a boy with infantile epileptic encephalopathy: case report". Brain & Development. 37 (4): 446–8. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2014.07.003. PMID 25085838.

- ^ Šimčíková D, Heneberg P (December 2019). "Refinement of evolutionary medicine predictions based on clinical evidence for the manifestations of Mendelian diseases". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18577. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54976-4. PMC 6901466. PMID 31819097.

- ^ Mangatt M, Wong K, Anderson B, Epstein A, Hodgetts S, Leonard H, Downs J (2016-01-01). "Prevalence and onset of comorbidities in the CDKL5 disorder differ from Rett syndrome". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 11: 39. doi:10.1186/s13023-016-0418-y. PMC 4832563. PMID 27080038.

- ^ "Infantile spasm syndrome, X-linked". Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ Kalscheuer VM, Tao J, Donnelly A, Hollway G, Schwinger E, Kübart S, Menzel C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tommerup N, Eyre H, Harbord M, Haan E, Sutherland GR, Ropers HH, Gécz J (June 2003). "Disruption of the serine/threonine kinase 9 gene causes severe X-linked infantile spasms and mental retardation". (primary). American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (6): 1401–11. doi:10.1086/375538. PMC 1180301. PMID 12736870.

- ^ West Syndrome

- ^ Kato M (August 2006). "A new paradigm for West syndrome based on molecular and cell biology". (secondary). Epilepsy Research. 70 Suppl 1: S87–95. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.008. PMID 16806828.

- ^ Fuchs C, Rimondini R, Viggiano R, Trazzi S, De Franceschi M, Bartesaghi R, Ciani E (2015). "Inhibition of GSK3β rescues hippocampal development and learning in a mouse model of CDKL5 disorder". Neurobiology of Disease. 82: 298–310. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2015.06.018. PMID 26143616.

- ^ Della Sala G, Putignano E, Chelini G, Melani R, Calcagno E, Michele Ratto G, Amendola E, Gross CT, Giustetto M, Pizzorusso T (2015). "Dendritic Spine Instability in a Mouse Model of CDKL5 Disorder Is Rescued by Insulin-like Growth Factor 1" (PDF). Biological Psychiatry. 80 (4): 302–311. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.028. hdl:2158/1012551. PMID 26452614.

- ^ Müller A, Helbig I, Jansen C, Bast T, Guerrini R, Jähn J, et al. (January 2016). "Retrospective evaluation of low long-term efficacy of antiepileptic drugs and ketogenic diet in 39 patients with CDKL5-related epilepsy". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 20 (1): 147–51. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.09.001. hdl:10067/1315500151162165141. PMID 26387070.

- ^ Aledo-Serrano Á, Gómez-Iglesias P, Toledano R, Garcia-Peñas JJ, Garcia-Morales I, Anciones C, Soto-Insuga V, Benke TA, Del Pino I, Gil-Nagel A (May 2021). "Sodium channel blockers for the treatment of epilepsy in CDKL5 deficiency disorder: Findings from a multicenter cohort". Epilepsy & Behavior. 118: 107946. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107946. PMID 33848848.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT02758626 for "Ataluren for Nonsense Mutation in CDKL5 and Dravet Syndrome" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "NICE recommends ataluren for treating Duchenne muscular dystrophy caused by a nonsense mutation". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Preclinical Program for Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-Like 5 (CDKL5) Deficiency". Amicus Therapeutics Press Release. 6 July 2016.

- ^ Montini E, Andolfi G, Caruso A, Buchner G, Walpole SM, Mariani M, Consalez G, Trump D, Ballabio A, Franco B (August 1998). "Identification and characterization of a novel serine-threonine kinase gene from the Xp22 region". (primary). Genomics. 51 (3): 427–33. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5391. PMID 9721213.

Further reading[]

- Ricciardi S, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Bienvenu T, Jacquette A, Landsberger N, Broccoli V (December 2009). "CDKL5 influences RNA splicing activity by its association to the nuclear speckle molecular machinery" (PDF). Human Molecular Genetics. 18 (23): 4590–602. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp426. PMID 19740913.

- Grosso S, Brogna A, Bazzotti S, Renieri A, Morgese G, Balestri P (May 2007). "Seizures and electroencephalographic findings in CDKL5 mutations: case report and review". Brain & Development. 29 (4): 239–42. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.001. PMID 17049193.

- Rosas-Vargas H, Bahi-Buisson N, Philippe C, Nectoux J, Girard B, N'Guyen Morel MA, Gitiaux C, Lazaro L, Odent S, Jonveaux P, Chelly J, Bienvenu T (March 2008). "Impairment of CDKL5 nuclear localisation as a cause for severe infantile encephalopathy". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (3): 172–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.053504. PMID 17993579.

- Bahi-Buisson N, Kaminska A, Boddaert N, Rio M, Afenjar A, Gérard M, Giuliano F, Motte J, Héron D, Morel MA, Plouin P, Richelme C, des Portes V, Dulac O, Philippe C, Chiron C, Nabbout R, Bienvenu T (June 2008). "The three stages of epilepsy in patients with CDKL5 mutations". Epilepsia. 49 (6): 1027–37. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01520.x. PMID 18266744.

- Mei D, Marini C, Novara F, Bernardina BD, Granata T, Fontana E, Parrini E, Ferrari AR, Murgia A, Zuffardi O, Guerrini R (April 2010). "Xp22.3 genomic deletions involving the CDKL5 gene in girls with early onset epileptic encephalopathy". Epilepsia. 51 (4): 647–54. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02308.x. PMID 19780792.

- Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Rosas-Vargas H, Milh M, Boddaert N, Girard B, Cances C, Ville D, Afenjar A, Rio M, Héron D, N'guyen Morel MA, Arzimanoglou A, Philippe C, Jonveaux P, Chelly J, Bienvenu T (October 2008). "Key clinical features to identify girls with CDKL5 mutations". Brain. 131 (Pt 10): 2647–61. doi:10.1093/brain/awn197. PMID 18790821.

- Nabbout R, Depienne C, Chipaux M, Girard B, Souville I, Trouillard O, Dulac O, Chelly J, Afenjar A, Héron D, Leguern E, Beldjord C, Bienvenu T, Bahi-Buisson N (November 2009). "CDKL5 and ARX mutations are not responsible for early onset severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy". Epilepsy Research. 87 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.07.004. PMID 19734009.

- Rusconi L, Salvatoni L, Giudici L, Bertani I, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Broccoli V, Landsberger N (October 2008). "CDKL5 expression is modulated during neuronal development and its subcellular distribution is tightly regulated by the C-terminal tail". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (44): 30101–11. doi:10.1074/jbc.M804613200. PMC 2662074. PMID 18701457.

- Nemos C, Lambert L, Giuliano F, Doray B, Roubertie A, Goldenberg A, Delobel B, Layet V, N'guyen MA, Saunier A, Verneau F, Jonveaux P, Philippe C (October 2009). "Mutational spectrum of CDKL5 in early-onset encephalopathies: a study of a large collection of French patients and review of the literature". Clinical Genetics. 76 (4): 357–71. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01194.x. PMID 19793311.

- Elia M, Falco M, Ferri R, Spalletta A, Bottitta M, Calabrese G, Carotenuto M, Musumeci SA, Lo Giudice M, Fichera M (September 2008). "CDKL5 mutations in boys with severe encephalopathy and early-onset intractable epilepsy". Neurology. 71 (13): 997–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000326592.37105.88. PMID 18809835.

- Barbe L, Lundberg E, Oksvold P, Stenius A, Lewin E, Björling E, Asplund A, Pontén F, Brismar H, Uhlén M, Andersson-Svahn H (March 2008). "Toward a confocal subcellular atlas of the human proteome". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 7 (3): 499–508. doi:10.1074/mcp.M700325-MCP200. PMID 18029348.

- Russo S, Marchi M, Cogliati F, Bonati MT, Pintaudi M, Veneselli E, Saletti V, Balestrini M, Ben-Zeev B, Larizza L (July 2009). "Novel mutations in the CDKL5 gene, predicted effects and associated phenotypes" (PDF). Neurogenetics. 10 (3): 241���50. doi:10.1007/s10048-009-0177-1. hdl:2434/70585. PMID 19241098.

- Li MR, Pan H, Bao XH, Zhu XW, Cao GN, Zhang YZ, Wu XR (February 2009). "[Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 gene and CDKL5 gene mutation in patients with Rett syndrome: analysis of 177 Chinese pediatric patients]". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 89 (4): 224–9. PMID 19552836.

- Li MR, Pan H, Bao XH, Zhang YZ, Wu XR (2007). "MECP2 and CDKL5 gene mutation analysis in Chinese patients with Rett syndrome". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1007/s10038-006-0079-0. PMID 17089071.

- Fichou Y, Bieth E, Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Girard B, Chelly J, Chaix Y, Bienvenu T (July 2009). "Re: CDKL5 mutations in boys with severe encephalopathy and early-onset intractable epilepsy". Neurology. 73 (1): 77–8, author reply 78. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000349658.05677.d7. PMID 19564592.

- Pintaudi M, Baglietto MG, Gaggero R, Parodi E, Pessagno A, Marchi M, Russo S, Veneselli E (February 2008). "Clinical and electroencephalographic features in patients with CDKL5 mutations: two new Italian cases and review of the literature". Epilepsy & Behavior. 12 (2): 326–31. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.10.010. PMID 18063413.

- Erez A, Patel AJ, Wang X, Xia Z, Bhatt SS, Craigen W, Cheung SW, Lewis RA, Fang P, Davenport SL, Stankiewicz P, Lalani SR (October 2009). "Alu-specific microhomology-mediated deletions in CDKL5 in females with early-onset seizure disorder". Neurogenetics. 10 (4): 363–9. doi:10.1007/s10048-009-0195-z. PMID 19471977.

- Psoni S, Willems PJ, Kanavakis E, Mavrou A, Frissyra H, Traeger-Synodinos J, Sofokleous C, Makrythanassis P, Kitsiou-Tzeli S (March 2010). "A novel p.Arg970X mutation in the last exon of the CDKL5 gene resulting in late-onset seizure disorder". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 14 (2): 188–91. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.03.006. PMID 19428276.

- Wu C, Ma MH, Brown KR, Geisler M, Li L, Tzeng E, Jia CY, Jurisica I, Li SS (June 2007). "Systematic identification of SH3 domain-mediated human protein-protein interactions by peptide array target screening". Proteomics. 7 (11): 1775–85. doi:10.1002/pmic.200601006. PMID 17474147.

External links[]

- Human CDKL5 genome location and CDKL5 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- CDKL5+protein,+human at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Cure CDKL5 Disorder resources for Families and Professionals - based in the UK

- International Foundation for CDKL5 Research - based in the US

- CDKL5 Forum - a professional forum to share current research on CDKL5 and to stimulate peer-group discussion

- CDKL5 Foundation Netherlands - CDKL5 Foundation based in holland for research, information and collaboration

- Genes on human chromosome X

- EC 2.7.11