Climate change in Europe

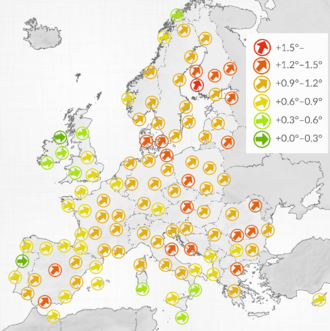

Climate change in Europe has resulted in an increase in temperature of 1.9°C (2019) in the EU compared to pre-industrial level. According to international climate experts, global temperature rise should not exceed 2 °C to prevent the most dangerous consequences of climate change, without Co2 emissions cut that could happen before 2050.[2][3] Emission reduction means development and implementation of new energy technology solutions. Some people consider that the technology revolution has already started in Europe, since the markets for renewable technology have annually grown.[4]

The European Union commissioner of climate action is Frans Timmermans since 1 December 2019.[5]

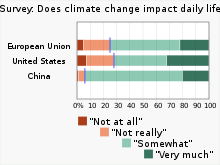

In European Investment Bank's Climate Survey of 2020, 90% of Europeans believe their children will experience the effects of climate change in their daily lives. [6][7] The survey showed a high concern for the climate from the 30 000 individuals surveyed, explaining that a majority of respondents are also prepared to pay a new tax in accordance with climate laws.[8][9] Only 9% of Europeans do not think climate change is occurring, compared to 18% in the United States.[10][11]

Greenhouse gas emissions[]

A 2016 European Environment Agency (EEA) report documents greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions between 1990 and 2014 for the EU-28 individual member states by IPCC sector.[12][13]

Total greenhouse gas emissions fell by 24% between 1990 and 2014, but road transport emissions rose by 17%. Cars, vans, and trucks had the largest absolute increase in CO

2 emissions of any sector over the last 25 years, growing by 124 Mt. Aviation also grew by 93 Mt over the same period, a massive 82% increase.

In 2019 European Union emissions reached 3.3 Gt (3.3 billion metric tons), 80% of which was from fossil fuels.[14]

In 2021, the European Parliament approved a landmark law setting GHG targets for 2050. The law aims to achieve climate neutrality and, after 2050, negative emissions[15] and paves the way for a policy overhaul in the European Union.[16] Under the law, the European Union must act to lower net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990). The law sets a limit of 225 Mt of CO

2 equivalent to the contribution of removals to the target.[15] According to Swedish lawmaker Jytte Guteland, the law would allow Europe to become the first carbon-neutral continent by 2050.[17]

Energy consumption[]

Coal[]

The coal consumption in Europe was 7,239 TWh in 1985 in 2020 it has fallen to 2,611 TWh. In the EU the coal consumption was 5,126 TWh in 1985 in 2020 it has fallen to 1,624 THw.[18] The height of Co2 emissions from coal in Europe were in 1987 with 3.31 billion tonnes, in 2019 the Co2 emissions were 1.36 billion tonnes.[19]

Russia had the most Co2 emissions from coal in Europe in 2019 (395.03 Mt), Germany had the second most Co2 emissions from coal in Europe (235.7 Mt).[20] Iceland's Co2 emissions from coal grew 151%, Turkey's Co2 emissions from coal grew 131% between and Montenegro Co2 emissions from coal grew 13% between 1990 and 2019, the rest of the European countries had a decrease in coal consumption in that period of time.[21]

From 2012 to 2018 in the EU coal fell by around 50TWh, compared to a rise of 30TWh in wind power and solar energy generation and a rise of 30TWh in gas generation. The remaining 10TWh covered a small structural increase in electricity consumption. In 2019 coal generation will be about 12% of the EU's 2019 greenhouse gas emissions.[22][23]

Fossil gas[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2021) |

According to Global Energy Monitor plans to expand infrastructure contradict EU climate goals.[24]

Agriculture[]

Greenhouse gases are also released through agriculture. Livestock production is common in Europe, responsible for 42% of land in Europe. This land use for livestock does affect the environment. Agriculture accounts for 10% of Europe's greenhouse gas emissions, this percentage being even larger in other parts of the world.[25] Along with this percentage agriculture is also responsible for being the largest contributor of non carbon dioxide greenhouse gas emissions being emitted annually in Europe.[26] Agriculture has been found to release other gases besides carbon dioxide such as methane and nitrous oxide. A study claimed that 38% of greenhouse gases released through agriculture in Europe were methane. These farms release methane through chemicals in fertilizers used, manure, and a process called enteric fermentation.[26] These gases are estimated to possibly cause even more damage than carbon dioxide, a study by Environmental Research Letters claims that "CH4 has 20 times more heat-trapping potential than CO2 and N2O has 300 times more."[27] These emissions released through agriculture are also linked to soil acidification and loss of bio diversity in Europe as well.[25]

Europe is attempting to take action. The Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) was created, focusing on lowering the amount of greenhouse gas emissions through land use in Europe. [26] Some success was seen, between 1990 and 2016, greenhouse gases emitted through agriculture in Europe decreased by 20%. However, the European Union has a plan to become carbon neutral by 2050. If more policies are not implemented or if there is no dietary shift, it has been concluded the European Union may not reach this goal.[26]

Transport[]

Shipping[]

Greenhouse gas emissions from shipping equal the carbon footprint of a quarter of passenger cars in Europe. In France, Germany, UK, Spain, Sweden and Finland shipping emissions in 2018 were larger than the emissions from all the passenger cars registered in 10 or more of the largest cities in each country. Despite the scale emissions, they are not part of emissions reduction targets made by countries as part of the Paris agreement on climate change.[28]

Other greenhouse gases[]

Hydrofluorocarbons[]

Trifluoromethane (HFC-23) is generated and emitted as a byproduct during the production of chlorodifluoromethane (HCFC-22). HCFC-22 is used both in emissive applications (primarily air conditioning and refrigeration) and as a feedstock for production of synthetic polymers. Because HCFC-22 depletes stratospheric ozone, its production for non-feedstock uses is scheduled to be phased out under the Montreal Protocol. However, feedstock production is permitted to continue indefinitely.

In the developed world, HFC-23 emissions decreased between 1990 and 2000 due to process optimization and thermal destruction, although there were increased emissions in the intervening years.

The United States (U.S.) and the European Union drove these trends in the developed world. Although emissions increased in the EU between 1990 and 1995 due to increased production of HCFC-22, a combination of process optimization and thermal oxidation led to a sharp decline in EU emissions after 1995, resulting in a net decrease in emissions of 67 percent for this region between 1990 and 2000.

Methane[]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2021) |

The decline in methane emissions from 1990 to 1995 in the OECD is largely due to non-climate regulatory programs and the collection and flaring or use of landfill methane. In many OECD countries, landfill methane emissions are not expected to grow, despite continued or even increased waste generation, because of non-climate change related regulations that result in mitigation of air emissions, collection of gas, or closure of facilities. A major driver in the OECD is the European Union Landfill Directive, which limits the amount of organic matter that can enter solid waste facilities. Although organic matter is expected to decrease rapidly in the EU, emissions occur as a result of total waste in place. Emissions will have a gradual decline over time.

Impacts on the natural environment[]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2021) |

Temperature and weather changes[]

According to European Environment Agency the temperature rose to 1.9°C in 2019 in 2010 it was 1.7°C, the temperatures in Europe are increasing faster than the world average. The global temperature change was 0.94°C in 2010 and rose to 1.03°C in 2019.[2]

The Artic sea ice decreased 33.000km2 between 1979 and 2020 per year during the winter and 79.000 km2 per year during the summer in the same period of time. If temperatures are kept below 1.5°C warming ice free Artic summers would be rare but it would be a frequent event with a 2°C warming.[29]

In the Baltic Sea ice melting has been seen since 1800 and with an acceleration happening since the 1980s. Sea ice was at a record low in the winter of 2019-2020.[29]

These extreme weather changes may increase the severity of diseases in animals as well as humans. The heat waves will increase the number of forest fires. Experts have warned that the climate change may increase the number of global climate refugees from 150 million in 2008 to 800 million in future. International agreement of refugees does not recognize the climate change refugees.

The summer of 2003 was probably the hottest in Europe since at latest ad 1500, unusually large numbers of heat-related deaths were reported in France, Germany and Italy. According to Nature (journal) it is very likely that the heat wave was human induced by greenhouse gases.[30]

A study of future changes in flood, heat-waves, and drought impacts for 571 European cities, using climate model runs from the coupled model intercomparison project Phase 5 (CMIP5) found that heat-wave days increase across all cities, but especially in southern Europe, whilst the greatest heatwave temperature increases are expected in central European cities. For the low impact scenario drought conditions intensify in southern European cities while river flooding worsens in northern European cities. However, the high impact scenario projects that most European cities will see increases in both drought and river flood risks. Over 100 cities are particularly vulnerable to two or more climate impacts.[31]

Extreme weather events[]

| Record meteorological events In Europe.[32] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| When | Where | What | Cost |

| 2003 | Europe | hottest summer in at least 500 years | 70,000 deaths |

| 2000 | England and Wales | wettest autumn on record since 1766 | £1.3 billion |

| 2007 | England and Wales | wettest July on record since 1766 | £3 billion |

| 2007 | Greece | hottest summer since 1891 | wildfires |

| 2010 | Russia | hottest summer since 1500 | $15 billion. 55,000 deaths |

| 2011 | France | hottest and driest spring since 1880 | grain harvest down by 12% |

| 2012 | Arctic | sea ice minimum | |

| Costs are estimates | |||

The summer of 2019 brought a series of high temperature records in Western Europe. During a heat wave a glaciological rarity in the form of a previously unseen lake emerged in the Mont Blanc Massif in the French Alps, at the foot of the Dent du Géant at an altitude of about 3400 meters, that was considered as evidence for the effects of global warming on the glaciers.[33][34][35]

Impacts on people[]

Health impacts[]

Heat waves[]

The summer of 2003 was probably the hottest in Europe since at least AD 1500, and unusually large numbers of heat-related deaths were reported in France, Germany and Italy. According to Nature, it is very likely that the heat wave was human-induced by greenhouse gases.[36] Because of climate change, 33% of Europeans feel they will have to relocate to a colder or warmer area or nation, according to the European Investment Bank's climate survey in 2020.[37][38]

A study of future changes in flood, heat-waves, and drought impacts for 571 European cities, using climate model runs from the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) found that heat-wave days increase across all cities, but especially in southern Europe, whilst the greatest heatwave temperature increases are expected in central European cities. For the low impact scenario, drought conditions intensify in southern European cities while river flooding worsens in northern European cities. However, the high impact scenario projects that most European cities will see increases in both drought and river flood risks. Over 100 cities are particularly vulnerable to two or more climate impacts.[39]

These extreme weather changes may increase the severity of diseases in animals as well as humans. The heat waves will increase the number of forest fires. Experts have warned that climate change may increase the number of global climate refugees from 150 million in 2008 to 800 million in future. International agreement of refugees does not recognize the climate change refugees.

The heat wave in 2018 in England, which would take hundreds of lives, would have had 30 times less of a chance of happening, without climate change. By 2050, such patterns would occur every 2 years if the current rate of warming continues.[40][41] In the absence of climate change, extreme heat waves in Europe would be expected to occur only once every several hundred years. In addition to hydrological changes, grain crops mature earlier at a higher temperature, which may reduce the critical growth period and lead to lower grain yields. The Russian heat wave in 2010 caused grain harvest down by 25%, government ban wheat exports, and losses were 1% of GDP. Russian heat wave 2010 estimate for deaths is 55,000.[32]

The heat wave in summer of 2019 as of June 28, claimed human lives, caused closing or taking special measures in 4,000 schools in France only, and big wildfires. Many areas declared state of emergency and advised the public to avoid "risky behaviour" like leaving children in cars or jogging outside in the middle of the day". The heatwave was made at least 5 times more likely by climate change and possibly even 100 times.[42]

Diseases[]

In 2019 for the first time, cases of Zika fever were diagnosed in Europe not because people traveled to tropical countries like Brazil, but from local mosquitos. Evidence indicating that the warming climate change in the area is the primary cause of this fever.[43]

Mitigation[]

In the beginning of the 21st century the European Union, began to conceive the European Green Deal as its main program of climate change mitigation.[44] The European Union claims that it has already achieved its 2020 target for emission reduction and has the legislation needed to achieve the 2030 targets. Already in 2018, its GHG emissions were 23% lower that in 1990.[45]

Paris Agreement[]

On April 22, 2016 the Paris Climate Accords were signed by all but three countries around the world. The conference to talk about this document was held in Paris, France. This put Europe in the epicenter of talks about the environment and climate change. The EU was the first major economy that decided to submit its intended contribution to the new agreement in March 2015. The EU ratified the Paris Agreement on October 5, 2015.[46]

In these talks the countries agreed that they all had a long-term goal of keeping global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius. They agreed that global emissions need to peak as soon as possible, and recognize that this will take longer for developing countries. On the subject of transparency the countries agreed that they would meet every five years to set ambitious goals, report their progress to the public and each other, and track progress for their long-term goals throughout a transparent and accountable system.[47]

The countries recognized the importance of non-party stakeholders to be involved in this process. Cities, regions, and local authorities are encouraged to uphold and promote regional and international cooperation.[47]

The Paris agreement is a legally international agreement, its main goal is to limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.[48] The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC's) are the plans to fight climate change adapted for each country.[49] Every party in the agreement has different targets based on its own historical climate records and country's circumstances and all the targets for each country are stated in their NDC.[50]

National determined goals based on NDC's[]

In the case for member countries of the European Union the goals are very similar and the European Union work with a common strategy within the Paris agreement. The NDC target for countries of the European Union against climate change and greenhouse gas emissions under the Paris agreement are the following:[51]

- 40% reduction in Greenhouse gas emissions until 2030, compared to 1990. This reduction is covered in these four sections;

- European Union Emission Trading System

- Outside the EU emissions trading system

- Land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF)

- Domestic institutional legislation and mitigation measure

- 55% reduction of greenhouse gases by domestic binding target without contribution from international credits, until 2030 compared to 1990.

- Gases covered in reduction: Carbon Dioxide (CO

2), Methane (CH

4), Nitrous oxide (N2O), Hydrofluorocarbon (HFCs), Perfluorinated compound (PFCs), Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). - 40% reduction of emissions from outside the European Union Emission Trading System (EU ETS) until 2030, compared to 2005.

Strategy to achieve NDC's[]

Each country has different ways to achieve the established goals depending on resources. In the case of the European union the following approach is established to support the NDC's climate change plan:[51]

- Each member state must report land use and subsequently report compensatory measures for the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Targets for improved energy efficiency and an increased amount of renewable energy have been established. Until the year 2030, energy consumption will be improved by 32.5%.

- The CO

2 emission per km must be reduced by 30–37.5% depending on vehicles by 2030 - Limit sales of F-gas, prohibited products and prevent emissions in existing products with F-gases. This is expected to reduce emissions of F-gases by 66% by 2030 compared to 2014.

- Multiannual Financial Framework,(MFF), for 2021–2027. MFF will finance climate action, such as policies and programs. MFF shall contribute to climate neutrality by 2050 and to achieving the 2030 climate targets.

- Within the European Union Emission Trading System (EU ETS) a cap on the maximum allowable amount of emissions established. From year 2021 this will also be applied in aviation. The EU ETS is an important tool in EU policy to reduce Greenhouse gas emission in a cost effective way. Under the 'cap and trade' principle, a maximum (cap) is set on the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by all participating installations.

Climate Targets[]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2021) |

The climate commitments of the European Union are divided into 3 main categories: targets for the year 2020, 2030 and 2050. The European Union claim that its policies are in line with the goal of the Paris Agreement.[52][53] The programm of response to climate change in Europe is called European Green Deal.[44] In April of the year 2020 the European Parliament called to include the European Green Deal in the recovery program from the COVID-19 pandemic.[54]

Targets for the year 2020:

- Reduce GHG emissions by 20% from the level in 1990.

- Produce 20% of energy from renewable sources.

- Increase Energy Efficiency by 20%[55].

Targets for the year 2030:

- Reduce GHG emission by 55% from the level in 1990.[56]

- Produce 32% of energy from renewables.

- Increase energy efficiency by 32.5%.[57]

Targets for the year 2050:

- Became climate neutral.[58]

Policies and legislation for mitigation[]

There is in place national legislation, international agreements and EU directives. The EU directive 2001/77/EU promotes renewable energy in electricity production. The climate subprogramme will provide €864 million in co-financing for climate projects between 2014 and 2020. Its main objectives are to contribute to the shift towards a low carbon and climate resilient economy and improve the development, implementation and enforcement of EU climate change policies and laws.[59]

In March of the year 2020 a draft of a climate law for the entire European Union was proposed. The law obliges the European Union to become carbon neutral by 2050 and adjust all its policies to the target. The law includes measures to increase the use of trains. The law includes a mechanism to check the implementation of the needed measures. It also should increase the climate ambitions of other countries. It includes a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism,[60] that will prevent Carbon leakage.[61] Greta Thunberg and other climate activist criticized the draft saying it has not enough strong targets[62]

In July 2021 The European Union published several drafts describing concrete measures to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Those include tax on jet fuel, a ban on selling cars on petrol and diesel by 2035, border tax, measures for increase energy efficiency in buildings and renewable energy.[63]

Stern report 2006[]

British government and economist Nicholas Stern published the Stern report in 2006. The Review states that climate change is the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen, presenting a unique challenge for economics. The Review provides prescriptions including environmental taxes to minimize the economic and social disruptions. The Stern Review's main conclusion is that the benefits of strong, early action on climate change far outweigh the costs of not acting.[64] The Review points to the potential impacts of climate change on water resources, food production, health, and the environment. According to the Review, without action, the overall costs of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) each year, now and forever. Including a wider range of risks and impacts could increase this to 20% of GDP or more.

No-one can predict the consequences of climate change with complete certainty; but we now know enough to understand the risks. The review leads to a simple conclusion: the benefits of strong, early action considerably outweigh the costs.[65]

Climate emergency[]

EU parliament declared climate emergency in November 2019. It urged all EU countries to commit to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. MEPs backed a tougher target of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030. The vote came as scientists warned that the world may have already crossed a series of climate tipping points, resulting in “a state of planetary emergency”.[66] The parliament also calls to end all fossil fuel subsidies by 2020, increase at least twice the payments to the green climate fund, make sure that all the legislation and the European budget will be in line with the 1.5 degrees target, and reduce emissions from aviation and shipping.[67]

Divestment from fossil fuels and sustainable investments[]

The European Investment Bank declared that it will divest almost completely from fossil fuels from the year 2021 and stopping to accept new projects already in 2019[68]

The central bank of Sweden sold its bonds in the provinces Queensland, Western Australia in Australia and the province Alberta from Canada because of severe climate impacts from those provinces[69]

In the end of November 2019, the European parliament adopted resolution calling to end all subsidies to fossil fuels by 2020[67]

In 2019 the European Parliament created rules for identification of sustainable investments. The measure should help achieve climate neutral Europe.[70]

[]

In May 2020, the €750 billion European recovery package and the €1 trillion budget were announced. The European Green deal is part of it. One of the principles is "Do no harm".The money will be spent only on projects that meet some green criteria. 25% of all funding will go to Climate change mitigation. Fossil fuels and Nuclear power are excluded from the funding. The recovery package is also should restore some equilibrium between rich and poor countries in the European Union.[71] In July the recovery package and the budget were generally accepted. The part of the money that should go to climate action raised to 30%. The plan includes some green taxation on European products and on import. But critics say it is still not enough for achieving the climate targets of the European Union and it is not clear how to ensure that all the money will really go to green projects[72]

Nature restoration and Agriculture[]

In May 2020, the European Union published 2 plans that are part of the European Green Deal: The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and From Farm to Fork.

In the official page of the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 is cited Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, saying that:

"Making nature healthy again is key to our physical and mental wellbeing and is an ally in the fight against climate change and disease outbreaks. It is at the heart of our growth strategy, the European Green Deal, and is part of a European recovery that gives more back to the planet than it takes away."[73]

The biodiversity strategy is an essential part of the climate change mitigation strategy of the European Union. From the 25% of the European budget that will go to fight climate change, large part will go to restore biodiversity and nature based solutions.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 include the next targets:

- Protect 30% of the sea territory and 30% of the land territory especially Old-growth forests.

- Plant 3 billion trees by the year 2030.

- Restore at least 25,000 kilometers of rivers, so they will become free flowing.

- Reduce the use of Pesticides by 50% by the year 2030.

- Increase Organic farming.

- Increase Biodiversity in agriculture.

- Give €20 billion per year to the issue and make it part of the business practice.

According to the page, approximately half of the global GDP depend on nature. In Europe many parts of the economy that generate trillions € per year, depend on nature. Only the benefits of Natura 2000 in Europe are €200 - €300 billion per year[73]

In the official page of the program From Farm to Fork is cited Frans Timmermans the Executive Vice-President of the European Commission, saying that:

"The coronavirus crisis has shown how vulnerable we all are, and how important it is to restore the balance between human activity and nature. At the heart of the Green Deal the Biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies point to a new and better balance of nature, food systems and biodiversity; to protect our people's health and well-being, and at the same time to increase the EU's competitiveness and resilience. These strategies are a crucial part of the great transition we are embarking upon."[74]

The program include the next targets:

- Making 25% of EU agriculture organic, by the year 2030.

- Reduce by 50% the use of Pesticides by the year 2030.

- Reduce the use of Fertilizers by 20% by the year 2030.

- Reduce nutrient loss by at least 50%.

- Reduce the use of antimicrobials in agriculture and antimicrobials in aquaculture by 50% by 2030.

- Create sustainable food labeling.

- Reduce food waste by 50% by 2030.

- Dedicate to R&I related to the issue €10 billion.[74]

Adaptation[]

Climate change threatens to undermine decades of development gains in Europe and put at risk efforts to eradicate poverty.[75] In 2013, the European Union adopted the 'EU Adaptation Strategy', which had three key objectives: (1) promoting action by member states, which includes providing funding, (2) promoting adaptation in climate-sensitive sectors and (3) research.[76]

Society and culture[]

Activism[]

The critics include that European companies, like in other OECD countries, have moved the energy intensive, polluting and climate gas emitting industry to Asia and South America. In respect to climate change there are no harmless areas. Carbon emissions from all countries are equal. The agreements exclude significant factors like deforestation, aviation and tourism, the actual end consumption of energy and the history of emissions. Negotiations are country oriented but the economical interests are in conflict between the energy producers, consumers and the environment.

School strike for climate[]

School strikes for climate became well known when the Swedish teen Greta Thunberg started to strike in the summer of 2018 and starting from September 2018 she began to strike every Friday.[77] The movement started to pick up in January 2019 with mass strikes happened in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland.[78][79][80] In the following months mass strikes were reported in numerous European countries. There were numerous global climate strikes that also took place in Europe on 15 March 2019,[81] 24 May 2019,[82] from 20–27 September 2019 (global climate action week),[83][84] 29 November 2019[85] and 25 September 2020. The strikes during 2020 were limited because of COVID-19.[86]

Extinction Rebellion[]

Extinction Rebellion (XR) was founded in 2018 in the United Kingdom and is a civil disobedience movement. Their first planned action was in London were 5000 demonstrators blocked the most important bridges of the city.[87] The movement quickly spread around Europe.[88][89] In October 2019 there was the first global rebellion with numerous demonstrations in European cities.[90]

By country[]

To learn more about climate change by European country, see the following articles:

EU countries[]

Austria[]

At the beginning of the year 2020, major parties in Austria reach a deal, including achieving carbon - neutrality of the country by 2040, produce all electricity from renewable sources by 2030, making a nationwide carbon tax and making a tax on flying, what should making trains more attractive.[91]

In 2020 the latest coal fired power station in the country was closed. Austria became the second country in Europe, after Belgium to become coal free. The goal of achieving 100% renewable electrycity by 2030 was adopted by government[92]

Belgium[]

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Cyprus[]

Denmark[]

In 2019 Denmark passed a law in which its pledge to reduce GHG emissions by 70% by 2030 from the level in 1990. It also pledged to achieve zero emissions by 2050. The law includes strong monitoring system and setting intermediate targets every 5 years. It includes a pledge to help climate action in other countries and consider climate impacts in diplomatic and economic relations with other countries.[97]

Greenland is an autonomous territory within Denmark. In 2021 Greenland banned all new oil and gas exploration on its territory. The government of Greenland explained the decision as follows: "price of oil extraction is too high,"[98]

Finland[]

France[]

Climate change in France has caused some of the greatest annual temperature increases registered in any country in Europe.[105] The 2019 heat wave saw record temperatures of 45.9 °C (114.6 °F).[106] Heat waves and other extreme weather events are expected to increase with continued climate change. Other expected environmental impacts include increased floods, due to both sea level rise and increased glacier melt.[107][108] These environmental changes will further lead to shifts in ecosystems and affect local organisms,[109] potentially leading to economic losses for example in the agriculture and fisheries sectors.[110][111]

France has set a law to have a net zero atmospheric greenhouse gas emission (carbon neutrality) by 2050.[112] Recently, the French government has received criticism for not doing enough to combat climate change, and in 2021 was found guilty in court for its insufficient efforts.[113]Germany[]

Climate change in Germany is leading to long-term impacts on agriculture in Germany, more intense heatwaves and coldwaves, flash and coastal flooding, and reduced water availability. Debates over how to address these long-term challenges caused by climate change have also sparked changes in the energy sector and in mitigation strategies. Germany's energiewende ("energy transition") has been a significant political issue in German politics that has made coalition talks difficult for Angela Merkel's CDU.[114]

Despite massive investments in renewable energy, Germany has struggled to reduce coal production and usage. The country remains Europe's largest importer of coal and produces the 2nd most amount of coal in the European Union behind Poland, about 1% of the global total.

German climate change policies started to be developed in around 1987 and have historically included consistent goal setting for emissions reductions (mitigation), promotion of renewable energy, energy efficiency standards, market based approaches to climate change, and voluntary agreements with industry. In 2021, the Federal Constitutional Court issued a landmark climate change ruling, which ordered the government to set clearer targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[115]Iceland[]

Iceland has a target of becoming carbon neutral by 2040.[116] It wants to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by the year 2030.[117]

Ireland[]

Italy[]

In 2019, Italy became the first country in the world to introduce mandatory lessons about sustainability and climate change. The lessons will be taught in all schools, in the ages 6 –19, one hour each week.[123] According to the European Investment Bank climate survey from 2020, 70% of Europeans have either switched to a green energy supplier or are prepared to do so. This ratio is 82% in Italy.[124][125]

Netherlands[]

Climate change in the Netherlands is already affecting the country. The average temperature in the Netherlands rose by almost 2 degrees Celsius from 1906 to 2017.[126]

The Netherlands has the fourth largest CO2 emissions per capita of the European Union.[127] These changes have resulted in increased frequency of droughts and heatwaves. Because significant portions of the Netherlands have been reclaimed from the sea or otherwise are very near sea level, the Netherlands is very vulnerable to sea level rise. The Dutch government has set goals to lower emissions in the next few decades. The Dutch response to climate change is driven by a number of unique factors, including larger green recovery plans by the European Union in the face of the COVID-19 and a climate change litigation case, State of the Netherlands v. Urgenda Foundation, which created mandatory climate change mitigation through emissions reductions 25% below 1990 levels.[128][129] At the end of 2018 CO2 emissions were down 15% compared to 1990 levels.[130] The goal of the Dutch government is to reduce emissions in 2030 by 49%.

Norway[]

Sweden[]

Spain[]

Non-EU countries[]

Russia[]

Turkey[]

Ukraine[]

The EU is trying to support a move away from coal.[152]

United Kingdom[]

Western Balkans[]

The EU is trying to support a move away from coal.[152]

See also[]

- Climate of Europe

- Eco-Management and Audit Scheme

- Energy policy of the European Union

- European Federation for Transport and Environment

- European Pollutant Emission Register (EPER)

- European Union Emission Trading Scheme

- List of European power companies by carbon intensity

- Renewable energy in the European Union

References[]

- ^ Kayser-Bril, Nicolas (24 September 2018). "Europe is getting warmer, and it's not looking like it's going to cool down anytime soon". EDJNet. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Global and European temperatures — Climate-ADAPT". climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ Carter, J.G. 2011, "Climate change adaptation in European cities", Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 193-198

- ^ Ilmastonmuutos otettiin yhä vakavammin[permanent dead link]; Yle 30.12.2008 (in Finnish)

- ^ Abnett, Kate (2020-04-21). "EU climate chief sees green strings for car scrappage schemes". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "THE EIB CLIMATE SURVEY 2019-2020" (PDF). 2020.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "THE EIB CLIMATE SURVEY 2019-2020" (PDF). 2020.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "THE EIB CLIMATE SURVEY 2019-2020" (PDF). 2020.

- ^ Annual European Union greenhouse gas inventory 1990–2014 and inventory report 2016: submission to the UNFCCC Secretariat — EEA Report No 15/2016. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Energy Agency (EEA). 17 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ^ "EU greenhouse gas emissions at lowest level since 1990". 21 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ^ Times, Sustainability (2021-06-29). "Why Europe cannot afford to shun nuclear power". Sustainability Times. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Council adopts European climate law". European Council. 2021-06-21. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (2021-06-24). "Climate 'law of laws' gets European Parliament's green light". MSN. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ^ ""Half-Measures and Broken Promises": European Parliament Commits to Climate Neutrality by 2050". Democracy Now!. 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ^ "Coal consumption". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ "Annual CO₂ emissions from coal". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ "Annual CO₂ emissions from coal". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ "Annual CO₂ emissions from coal". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ Europe's Great Coal Collapse of 2019 Sandbag UK 18.9.2019

- ^ EU på väg att lämna kolkraften – Allt mer vindkraft och solenergi i stället Vasabladet 18.9.2019

- ^ Inman, Mason; Aitken, Greig; Zimmerman, Scott (2021-04-07). "Europe Gas Tracker Report 2021". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Leip, Adrian (2015-11-04). "Impacts of European livestock production: nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus and greenhouse gas emissions, land-use, water eutrophication and biodiversity". Environmental Research Letters. 10 (11): 115004. Bibcode:2015ERL....10k5004L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/115004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Climate change adaptation in the agriculture sector in Europe — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ "Agriculture and Climate Change in the EU: An Overview | Climate Policy Info Hub". climatepolicyinfohub.eu. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- ^ European shipping emissions undermining international climate targets, Report says greenhouse gas emissions equal carbon footprint of a quarter of passenger cars The Guardian 9 Dec 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Arctic and Baltic sea ice — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- ^ Stott, Peter A.; Stone, D. A.; Allen, M. R. (2004). "Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003". Nature. 432 (7017): 610–614. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..610S. doi:10.1038/nature03089. PMID 15577907. S2CID 13882658.

- ^ Guerreiro, Selma B.; Dawson, Richard J.; Kilsby, Chris; Lewis, Elizabeth; Ford, Alistair (2018). "Future heat-waves, droughts and floods in 571 European cities". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (3): 034009. Bibcode:2018ERL....13c4009G. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aaaad3. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Why a 4 degree centrigrade warmer world must be avoided November 2012 World Bank

- ^ Climat : un lac s'est formé sur le Mont Blanc à 3 000 mètres d’altitude - Un lac a été découvert sur le Mont Blanc, à un peu plus de 3 000 mètres d'altitude, entre la Dent du Géant et le Col de Rochefort

- ^ A Hiker Found This Beautiful Lake In The Alps. There's Just One Small Problem

- ^ La formation d'un lac dans le massif du Mont-Blanc est-elle liée au réchauffement climatique?

- ^ Stott, Peter A.; Stone, D. A.; Allen, M. R. (2004). "Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003". Nature. 432 (7017): 610–614. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..610S. doi:10.1038/nature03089. PMID 15577907. S2CID 13882658.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "THE EIB CLIMATE SURVEY 2019-2020" (PDF). 2020.

- ^ Guerreiro, Selma B.; Dawson, Richard J.; Kilsby, Chris; Lewis, Elizabeth; Ford, Alistair (2018). "Future heat-waves, droughts and floods in 571 European cities". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (3): 034009. Bibcode:2018ERL....13c4009G. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aaaad3. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ "2018 UK summer heatwave made thirty times more likely due to climate change". The Met Office. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (6 December 2018). "Climate change made UK heatwave 30 times more likely – Met Office". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (2 July 2019). "Climate change: Heatwave made 'at least' five times more likely by warming". BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Davidson, Jordan (November 8, 2019). "'We Now Have a New Exotic Disease in Europe': Native Zika Virus Spreads Due to Climate Change". Ecowatch. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A European Green Deal". European Commission. European Union. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "Progress made in cutting emissions". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Gould, Rebecca Harrington, Skye. "The US will join Syria and Nicaragua as the only nations that aren't part of the Paris agreement". Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anonymous (2016-11-23). "Paris Agreement". Climate Action - European Commission. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ United Nations, United Nations Climate Change. "The Paris Agreement". unfccc.int. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ "NDC spotlight". UNFCCC. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Nationally Determined Contributions". unfccc. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The update of the nationally determined contribution of Luxemburg" (PDF). UNFCCC. 2020-12-17. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "2050 long-term strategy". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "Paris Agreement". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "COVID-19: MEPs call for massive recovery package and Coronavirus Solidarity Fund". European Parliament. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "2020 climate & energy package". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "State of the Union: Commission raises climate ambition and proposes 55% cut in emissions by 2030". European Commission website. European Union. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "2030 climate & energy framework". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "2050 long-term strategy". European Commission. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/budget/life_en

- ^ "Committing to climate-neutrality by 2050: Commission proposes European Climate Law and consults on the European Climate Pact". European Commission. European Union. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ "EU Green Deal (carbon border adjustment mechanism)". European Commission. European Union. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Pronczuk, Monika (4 March 2020). "E.U. Proposes a Climate Law. Greta Thunberg Hears 'Empty Words.'". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ "EU unveils sweeping climate change plan". BBC. 15 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Stern, N. (2006). "Summary of Conclusions". Executive summary (short) (PDF). Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change (pre-publication edition). HM Treasury. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ^ Sir Nicholas Stern: Stern Review : The Economics of Climate Change, Executive Summary,10/2006 Archived September 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 'Our house is on fire': EU parliament declares climate emergency The Guardian 28 Nov 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The European Parliament declares climate emergency". European Parliament. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian; Henley, Jon (15 November 2019). "European Investment Bank to phase out fossil fuel financing". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Sweden's central bank dumps Australian bonds over high emissions". The Guardian. Reuters. 14 November 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Climate change: new rules agreed to determine which investments are green". European Parliament. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (27 May 2020). "'Do no harm': EU recovery fund has green strings attached". Euroacrtive. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (21 July 2020). "Factbox: How 'green' is the EU's recovery deal?". Reuters. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030". European Commission website. European Union. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "From Farm to Fork". European Commission website. European Union. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep (2018). Climate Change Adaptation in Europe and Central Asia: Adapting to a changing climate for resilient development. UNDP.

- ^ Staff (2016-11-23). "EU Adaptation Strategy". Climate Action - European Commission. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- ^ Gould, Liam (2019-08-20). "How Greta Thunberg's climate strikes became a global movement in a year". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "12,000+ Belgian Students Skip School to Demand Climate Action". EcoWatch. 2019-01-18. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Swiss youths strike for climate protection". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Schüler streiken für Klimaschutz: "It's our fucking future" | MDR.DE". 2019-02-18. Archived from the original on 2019-02-18. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Climate strikes: Students in 123 countries take part in marches". euronews. 2019-03-15. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Students From 1,600 Cities Just Walked Out of School to Protest Climate Change. It Could Be Greta Thunberg's Biggest Strike Yet". Time. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Across the globe, millions join biggest climate protest ever". the Guardian. 2019-09-20. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Climate crisis: 6 million people join latest wave of global protests". the Guardian. 2019-09-27. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Global climate protests ahead of Madrid meeting". AP NEWS. 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Fridays for Future: Climate strikers are back on the streets | DW | 25.09.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "What is Extinction Rebellion and what does it want?". BBC News. 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ "Fine Gael criticised for 'self-congratulation' on climate change". 2018-11-17. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Extinction Rebellion: The activists risking prison to save the planet | DW | 15.04.2019". DW.COM. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ "Extinction Rebellion plans new London climate crisis shutdowns". the Guardian. 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ "Austria's New Government Sets Goal to Be Carbon Neutral by 2040". Deutche Welle. Ecowatch. 3 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (20 April 2020). "Austria becomes second EU country to exit coal". EURACTIV. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Per capita CO₂ emissions". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ "Evolutie". Klimaat | Climat (in Dutch). Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ "Waargenomen veranderingen". Klimaat | Climat (in Dutch). Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ "Climate Change and Impact". The Cyprus Institute. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ^ Timperley, Jocelyn (2019-12-06). "Denmark adopts climate law to cut emissions 70% by 2030". Climate Home News. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ COHEN, LI (16 July 2021). "Greenland halts new oil exploration to combat climate change and focus on sustainable development". CBC. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Which nations are most responsible for climate change? Guardian 21 April 2011

- ^ Pipatti, Riitta. "Statistics Finland - Greenhouse gases". www.stat.fi. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ^ Finland far behind climate goals, think tank says YLE 22.1.2020

- ^ Europe's Great Coal Collapse of 2019 Sandbag UK 18.9.2019

- ^ Darby, Megan. "Finland to be carbon neutral by 2035. One of the fastest targets ever set". Climate Home News. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Finland will achieve carbon neutrality by 2035". Sustanable Development Goals. United Nations. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ National Observatory for the Impacts of Global Warming. Climate change: costs of impacts and lines of adaptation. Report to the Prime Minister and Parliament, 2009. Accessed 2021-08-21

- ^ "France records all-time highest temperature of 45.9C". The Guardian. 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ "Coastal floods in France". Climatechangepost.com. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ "Glacial Retreat in the Alps".

- ^ "Climate change and its impacts in the Alps". Crea Mont Blanc. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ AgriAdapt. SUSTAINABLE ADAPTATION OF TYPICAL EU FARMING SYSTEMS TO CLIMATE CHANGE. Retrieved 2021-04-26

- ^ Mcilgorm A, Hanna S, Knapp G, Le floc'h P, Millerd F, Pan M. (2010). "How will climate change alter fishery governance? Insights from seven international case studies". Marine Policy. 3 (1): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2009.06.004 – via Research gate.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "What is carbon neutrality and how can it be achieved by 2050? | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 2019-03-10. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ "Court convicts French state for failure to address climate crisis". The Guardian. 2021-02-03. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "German election: Preliminary coalition talks collapse after FDP walks out | News | DW | 19.11.2017". DW.COM. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (29 April 2021). "German Court Orders Revisions To Climate Law, Citing 'Major Burdens' On Youth". NPR. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "Climate Change". Government of Iceland. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "The European Union, Iceland and Norway agree to deepen their cooperation in climate action". Climate Action. European Union. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Taggart, Emma (24 July 2021). "'Irish temperature records will be broken in the coming years because we're in a climate crisis'". TheJournal.ie. The Journal. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Ireland's climate likely to drastically change by 2050". Green News Ireland. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Environment, Kevin O'Sullivan; Editor, Science (21 May 2020). "Over 70,000 Irish addresses at risk of coastal flooding by 2050". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 July 2021.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Climate change and health". HSE.ie. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ O'Connor, Niall. "Head of Defence Forces says climate change is single biggest threat to Ireland". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ Squires, Nick (5 November 2019). "Italy to become first country to make studying climate change compulsory in schools". The Telegrafh. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "EU/China/US climate survey shows public optimism about reversing climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ "THE EIB CLIMATE SURVEY 2019-2020" (PDF). 2020.

- ^ "klimaatverandering". Milieu centraal (in Dutch).

- ^ "Per capita CO₂ emissions". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ "Netherlands climate change: Court orders bigger cuts in emissions". BBC. 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Activists cheer victory in landmark Dutch climate case". Associated Press. 20 December 2019.

- ^ Statistiek, Centraal Bureau voor de. "Lagere broeikasgasuitstoot". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (in Dutch). Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.CIA.gov. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "Vannkraftpotensialet". nve.no.

- ^ "Norway: Carbon-neutral as soon as 2030". Nordic Energy Research. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Norway steps up 2030 climate goal to at least 50 % towards 55 %". Government.no. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Renewables 2014 Global Status Report, page 29

- ^ Tamanini, Jeremy; Dual Citizen LLC (September 2016). Global Green Economy Index 2016. Dual Citizen LLC.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SOU 2007:60 Sweden facing climate change – threats and opportunities". www.government.se.

- ^ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ Tasca, Miguel Ángel Medina, Elisa (2021-08-12). "Weather experts on Spain's heatwave: 'A summer like this will be considered cold in 30 years' time'". EL PAÍS. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ IPCC Working group III fourth assessment report, Summary for Policymakers 2007[permanent dead link]

- ^ Şen, Prof. Dr. Ömer Lütfi. "Climate Change in Turkey". Mercator-IPC Fellowship Program. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Monthly and Seasonal Trend Analysis of Maximum Temperatures over Turkey" (PDF). International Journal of Engineering Science and Computing. 7 (11). November 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Climate change responsible for spring and winter within weeks". Climate change responsible for spring and winter within weeks. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ "Turkey battles climate change: Nationwide efforts give hope for the future". Daily Sabah. 11 October 2018.

- ^ Turkey's fourth biennial report. Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (Report). December 2019.

- ^ "Extreme weather threatens Turkey amid climate change fears". Daily Sabah. 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Turkey drought: Istanbul could run out of water in 45 days". The Guardian. 2021-01-13.

- ^ "'Food insecurity Turkey's top climate change risk'". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ "Climate". climatechangeinturkey.com. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Each Country's Share of CO2 Emissions". Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Fossil Fuel Support - TUR", OECD, accessed September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Commission launches the secretariat of a new initiative for coal regions in transition in the Western Balkans and Ukraine". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ "Heavier rainfall from storms '100% for certain' linked to climate crisis, experts warn". The Independent. 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Climate Change Act". Climate Change Laws of the World. Grantham Research Institute, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia Law School.

- ^ Shepheard, Marcus. "UK net zero target". Institute for government. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "UK Parliament declares climate emergency". 1 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

External links[]

- Climate change in Europe

- Natural disasters in Europe

- Climate change by continent

- Climate change by country and region