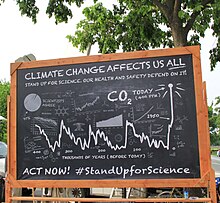

Individual action on climate change

Individual action on climate change can include personal choices in many areas, such as diet, means of long- and short-distance travel, household energy use, consumption of goods and services, and family size. Individuals can also engage in local and political advocacy around issues of climate change.

As of 2020, emissions budgets are uncertain but estimates of the annual average carbon footprint per person required to meet the target of limiting global warming to 2 degrees by 2100 are all below the world average of about 5 tonnes CO

2-equivalent.[1][2][3][4]

The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report emphasizes that behavior, lifestyle and cultural change have a high mitigation potential in some sectors, particularly when complementing technological and structural change.[5]: 20 In general, higher consumption lifestyles have a greater environmental impact, with the richest 10% of people emitting about half the total lifestyle emissions.[6][7]

Several scientific studies have shown that when people, especially those living in developed countries but more generally including all countries, wish to reduce their carbon footprint, there are a few key "high-impact" actions they can take such as[8][9] having one fewer child,[dubious ] living car-free, avoiding one round-trip transatlantic flight, and eating a plant-based diet. These differ significantly from much popular advice for "greening" one's lifestyle, which seem to fall mostly into the "low-impact" category.[8][9] But according to others avoiding meat and dairy foods is the single biggest way an individual can reduce their environmental impact.[10]

Some commentators have argued that individual actions as consumers and "greening personal lives" are insignificant in comparison to collective action, especially actions that hold the fossil fuel corporations accountable for producing 71% of carbon emissions since 1988.[11][12][13] The concept of a personal carbon footprint and calculating one's footprint was popularized by oil producer BP as "effective propaganda" as way to shift their responsibility to "linguistically... remove itself as a contributor to the problem of climate change".[14] Others have shown that sometimes individual measures may effectively undermine political support for structural measures. In one example researchers found that "a green energy default nudge diminishes support for a carbon tax."[15]

Others say that individual action leads to collective action, and emphasize that "research on social behavior suggests lifestyle change can build momentum for systemic change."[16] Furthermore, if individuals shrink their consumption of fossil fuel products, fossil fuel corporations are incentivized to produce less, as the demand for their product would decrease.[17] In other words, each individual's consumption plays a role in the total supply of fossil fuels and emission of greenhouse gases.

Suggested individual target amount[]

As of 2021 the remaining carbon budget for a 50-50 chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of warming is 460 bn tonnes of CO2 or 11 and a half years at 2020 emission rates.[19] Global average greenhouse gas per person per year in the late 2010s was about 7 tonnes[20] - including 0.7 tonnes CO2eq food, 1.1 tonnes from the home, and 0.8 tonnes from transport.[21] To meet the Paris Agreement target of under 1.5 degrees warming by the end of the century, estimates of the annual carbon footprint per person required by 2030 vary from 2.5[22] to 4.5 tonnes.[1] As of 2020 the average Indian meets this target,[23] the average person in France[24] or China exceeds it, and the average person in the USA and Australia vastly exceeds it. Per capita emissions also vary significantly within countries, with wealthier individuals creating more emissions.[25][26] A 2015 Oxfam report calculated that the wealthiest 10% of the global population were responsible for half of all greenhouse gas emissions.[27] According to a 2021 report by the UN, the wealthiest 5% contributed nearly 40% of emissions growth from 1990 to 2015.[28]

Scope: meaning of "lifestyle carbon footprint"[]

In 2008 the World Health Organization wrote that "Your 'carbon footprint' is a measure of the impact your activities have on the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2 ) produced through the burning of fossil fuels".[29] In 2019 the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies in Japan defined "lifestyle carbon footprint" as "GHG emissions directly emitted and indirectly induced from the final consumption of households, excluding those induced by government consumption and capital formation such as infrastructure."[22]: v However an Oxfam and SEI study in 2020 estimated per capita CO2 emissions rather than CO2-equivalent, and allocated all consumption emissions to individuals rather than just household consumption.[30] According to a 2020 review many academic studies do not properly explain the scope of the "personal carbon footprint" they study.[31]

Family size[]

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2019) |

It is also time to re-examine and change our individual behaviors, including limiting our own reproduction (ideally to replacement level at most) and drastically diminishing our per capita consumption of fossil fuels, meat, and other resources.

—William J. Ripple, lead author of the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice, BioScience, 2017.[32]

Although having fewer children is arguably the individual action that most effectively reduces a person's climate impact, the issue is rarely raised, and it is arguably controversial due to its private nature. Even so, ethicists,[33][34] some politicians such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,[35] and others[9][36][37][38] have started discussing the climate implications associated with reproduction. Researchers have found that some people (in wealthy countries) are having fewer biological children due to their concerns about the carbon footprint of reproduction,[39][need quotation to verify] as well as beliefs that they can do more to slow climate change if they do not have children.[40]

It has been claimed that not having an additional child saves "an average for developed countries"[a] of 58.6[b] tonnesCO

2-equivalent (tCO2e) emission reductions per year[8][dubious ] and "a US family who chooses to have one fewer child would provide the same level of emissions reductions as 684 teenagers who choose to adopt comprehensive recycling for the rest of their lives."[8][9] This is based on the premise that a person is responsible for the carbon emissions of their descendants, weighted by relatedness (the person is responsible for half their children's emissions, a quarter of their grandchildren's and so on).[42] This has been criticised: both as a category mistake for assigning descendants emissions to their ancestors[43] and for the very long timescale of reductions.[44] An April 2020 study published in PLOS One found that, among two-adult Swedish households, those with children increased carbon emission in two ways, by adding to the population and by increasing their own carbon emissions by consuming greater quantities of meat and gasoline for transportation than their counterparts without children; an increase of some 25% more than the latter. According to one of the contributors to the study, University of Wyoming economist Linda Thunstrom, "If we're finding these results in Sweden, it's pretty safe to assume that the disparity in carbon footprints between parents and non-parents is even bigger in most other Western countries."[45]

Two interrelated aspects of this action, family planning and women and girl's education, are modeled by Project Drawdown as the #6 and #7 top potential solutions for climate change, based on the ability of family planning and education to reduce the growth of the overall global population.[46][47] In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss." The policies they promote, which "are proven and effective policies that strengthen human rights while lowering fertility rates," would include removing barriers to gender equality, especially in education, and ensuring family planning services are available to all.[48][49]

Travel and commuting[]

There are many options to choose from when considering alternatives to personal car use, but the use of a personal vehicle may be necessary due to location and accessibility reasons.[50] The life cycle assessment of a vehicle evaluates the environmental impact of the production of the vehicle and its spare parts, the fuel consumption of the vehicle, and what happens to the vehicle at the end of its lifespan.[51] These environmental impacts can be measured in greenhouse gas emissions, solid waste produced, and consumption of energy resources among other factors.[51] Increasingly common alternatives to internal-combustion engines vehicles (ICEVs) are hybrid, electric vehicles (EVs), and hybrid-electric vehicles.[52] EVs and other new vehicle technologies use many of the same parts as ICEV, besides the engines and other key components, so it can be assumed that there is little difference between the amount of energy it takes to produce the body of the car itself.[52] EVs can release lower emissions than ICE vehicles, but it depends on factors such as traffic patterns, how electricity is generated in an area, and the size of the vehicle.[53] Some other alternatives to reducing emissions while driving a personal vehicle are planning out trips beforehand so they follow the shortest route and/or the route with the least amount of traffic.[54] Following a route with less traffic can reduce idling and waste less fuel.

Carpooling and ride-sharing services are also alternatives to personal transportation. Carpooling reduces the amount of cars on the road, in turn reducing the amount of traffic and energy consumption. A 2009 study estimated that 7.2 million tons of green-house gas emissions could be avoided if one out of 100 vehicles carried one extra passenger.[55] Ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft could be viable options for transportation, but according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, ride-share service trips currently result in an estimated 69% increase in climate pollution on average.[56] More pollution is generated as the amount of time and energy a ride-share driver spends between customers with no passengers increases.[56] There are also more vehicles on the road as a result of passengers who would have otherwise taken public transportation, walked, or biked to their destination.[56] Ride-sharing services can reduce emissions if they implement strategies like electrifying vehicles and increase carpooling trips.[56] In some cities, there are car-sharing services where the user can gain short-term access to a vehicle when other options are not available.[57]

Walking and biking emit little to no greenhouse gases and are healthy alternatives to driving or riding public transportation.[58] There are also increasing numbers of bike-sharing services in urban environments.[59] An individual can rent a bike for a period of time, reducing the financial burden of buying a personal bike and its associated life assessment cycle.[59]

Reliable public transportation is one of the most viable alternatives to driving personal vehicles. While there are efficiency problems associated with public transportation (waiting times, missed transfers, unreliable schedules, energy consumption), they can be improved as funding and public interest increases and technology advances.[60] A case study from Auckland, New Zealand found that the global warming potential (GWP) of a bus system decreased by 5.6% when a system used increased efficiency methods compared to a system with no controls implemented.[60]

In the early 21st century perception towards climate change influenced some people in rich countries to change their travel lifestyle.[61]

Air transport[]

Air travel is one of the most emission-intensive modes of transportation.[62] The current most effective way to reduce personal emissions from air travel is to fly less.[63] New technologies are being developed to allow for more efficient fuel consumption and planes powered by electricity.[63]

Avoiding air travel and particularly frequent flyer programs[64] has a high benefit because the convenience makes frequent, long-distance travel easy, and high-altitude emissions are more potent for the climate than the same emissions made at ground level. Aviation is much more difficult to fix technically than surface transport,[65] so will need more individual action in future if the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation cannot be made to work properly.[66]

Flying is responsible for 5 percent of global warming".[67] The number of planes in the sky can be anywhere from 8,000 to 20,000 planes flying in the Troposphere. Depending on if these planes are domestic or flying international, these planes carry anywhere from 90 to 544 passengers per flight. Compared to longer flight routes, shorter flights actually produce larger amounts of greenhouse gas emissions per passenger they carry and mile covered. Airplanes contribute to damaging our environment since airplanes cause greater air pollution as they release carbon dioxide along with nitrogen oxides, which is an atmospheric pollutant. These gases lead to the formation of the greenhouse gas ozone. Ozone has a greater concentration level in higher altitudes than being on the ground. The carbon in the fuel which jets burn gets released into the atmosphere forming carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere also causes ocean acidification, the decrease in the pH of the oceans. Ocean acidification causes a shift in the water's pH balance from seawater to acidic water. While it may seem that one plane ride will not cause much damage, over time the carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxides do contribute to climate change.

Surface transport[]

- Walking and running are among the least environmentally harmful modes of transportation.

- Cycling follows walking and running as having a low impact on the environment.

- Public transport such as electric buses, metro and electric trains generally emit less greenhouse gases than cars per passenger.

- Electric kick scooters can also be a low-impact form of transportation if they have long lifetimes.[68]

- Cars: Using an electric car instead of a gasoline or diesel car helps to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

- Going car-free may be the most effective action an individual can take, according to the BBC.[69]

Diet and food[]

The world’s food system is responsible for about one-quarter of the planet-warming greenhouse gases that humans generate each year.[70] The 2019 World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency, endorsed by over 11,000 scientists from more than 150 countries, stated that "eating mostly plant-based foods while reducing the global consumption of animal products, especially ruminant livestock, can improve human health and significantly lower GHG emissions."[71]

Agriculture is very difficult to fix technically so will need more individual action[10] or carbon offsetting than all other sectors except perhaps aviation.[65]

Eating less meat, especially beef and lamb, reduces emissions.[72] A diet which is part of individual action on climate change is also good for health, averaging less than 15g (about half an ounce) of red meat and 250g dairy (about one glass of milk) per day.[73] The World Health Organization recommends trans-fats make up less than 1% of total energy intake: ruminant trans-fats are found in beef, lamb, milk and cheese.[74] In 2019, the IPCC released a summary of the 2019 special report which asserted that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Ecologist Hans-Otto Pörtner, who contributed to the report, said "We don't want to tell people what to eat, but it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect."[75]

Meats such as beef have a higher climate impact since cows release methane, a greenhouse gas that is more harmful than carbon dioxide. Overbreeding this animal for beef just increases the amount of methane in an environment that is already high.[76] Eating too much red meat not only affects the climate but can also be unhealthy.[77]

Eating a plant-rich diet is listed as the #4 solution for climate change as modeled by Project Drawdown, based on avoided emissions from the production of animals and avoided emissions from additional deforestation for grazing land.[78]

A 2018 study indicated that one fifth of Americans are responsible for about half of the country's diet-related carbon emissions, due mostly to eating high levels of meat, especially beef.[79][80]

Home energy, landscaping and consumption[]

Reducing home energy use through measures such as insulation, better energy efficiency of appliances, cool roofs, heat reflective paints,[81] lowering water heater temperature, and improving heating and cooling efficiency can significantly reduce an individual's carbon footprint.[82]

In addition, the choice of energy used to heat, cool, and power homes makes a difference in the carbon footprint of individual homes.[83] Many energy suppliers in various countries worldwide have options to purchase part or pure "green energy" (usually electricity but occasionally also gas).[84] These methods of energy production emit almost no greenhouse gases once they are up and running.

Installing rooftop solar, both on a household and community scale, also drastically reduces household emissions, and at scale could be a major contributor to greenhouse gas abatement.[85]

Low energy products and consumption[]

Labels, such as Energy Star in the US, can be seen on many household appliances, home electronics, office equipment, heating and cooling equipment, windows, residential light fixtures, and other products. Energy star is a program in the U.S. that promotes energy efficiency. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. The Department of Energy runs the program, and they produce energy-efficient products, which help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to data found by energysage.com[86] Energy star appliance lasts for 10 to 20 years and uses anywhere from 10 to 50 percent less energy each year than a non-energy efficient equivalent.

Carbon emission labels describe the carbon dioxide emissions created as a by-product of manufacturing, transporting, or disposing of a consumer product.

Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) "present transparent, verified and comparable information about the life-cycle environmental impact of products."[87]

These labels may help consumers choose lower energy products.

Landscape and gardens[]

Protecting forests and planting new trees contributes to the absorption of carbon dioxide from the air. There are many opportunities to plant trees in the yard, along roads, in parks, and in public gardens. In addition, some charities plant fast-growing trees—for as little as $US0.10 per tree—to help people in tropical developing countries restore the productivity of their lands.[88]

Turfgrass lawns can contribute[quantify] to climate change through the impacts of fertilizers, herbicides, irrigation, and gas-powered lawnmowers and other tools; depending on how lawns are managed, the impact of emissions from maintenance and chemicals may outweigh any carbon sequestration from the lawn.[89][90] Reducing irrigation, reducing chemical use, planting native plants or bushes, and using hand tools can all reduce the climate impact of lawns.[91]

In addition to planting Victory Gardens which provide locally grown food,[92] gardeners may wish to experiment with companion planting of diverse species of plants and trees, in order to develop novel carbon sequestration and NOx reduction techniques suitable for their local area.[93][94][95]

Laundry and choice of clothing[]

Using a shorter, cold water wash cycle can conserve energy by as much as 66%, while simultaneously reducing color loss and shedding of microfibers into the environment.[96] Hanging laundry to dry also saves energy and reduces carbon footprint.[97][98][99][100]

Purchasing well-made, durable clothing, and avoiding "fast fashion" is critical for reducing climate impact.[101][102][103]

Producing raw materials such as clothing has a big impact on our environment. Factors such as spinning material into fibers, dyeing, and weaving require massive amounts of water and chemicals. Some materials such as cotton require pesticides like Aldicarb for growing as cotton. "The World Resources Institute estimates that the so-called "fast fashion" industry annually releases about 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming" [104][failed verification] Not only is making clothes hurtful to the environment but getting rid of clothes also hurts the environment. According to PlanetAid.Org "Clothing is the second-largest pollution source in the world". Some clothing is donated and recycled, meanwhile, the rest of the waste heads to landfills where they release "greenhouse gases and leach toxins and dyes into the surrounding soil and water".[104]

Choice of stove[]

The choice of stove may vary depending on location.

Electric stoves are preferable to natural gas in locations where the electric grid has a high proportion of renewable energy, such as California.[105]

Rocket stoves and other biomass stoves are important in developing countries to conserve wood.[106] The UN seeks to phase out wood-burning cookstoves.[107]

Solar cookers are an environmentally sound choice.[108] A solar cooker is a device which uses the energy of direct sunlight to heat and cook food materials. They need no fuel to operate [109] Solar cookers are bowls that reflect sunlight toward a pan and convert sunlight to heat energy inside the cooker to operate and require no fuel or electricity.

Solar cooking has been practical for households in the highlands of China and Tibet, where "solar irradiation levels are high, cooking traditions correspond to the use of a solar cooker" and biomass is not readily available.[110][111] Institutional level solar cooking has enabled temples in India to earn money through carbon credits.[112][113]

Digital hygiene[]

Curbing unnecessary use of digital data, such as the use of some types of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin,[114] has a small but measurable impact on individual carbon emissions.

Less consumption of goods and services[]

The production of many goods and services results in the emission of greenhouse gases as well as pollution. One way for individuals to decrease their environmental footprint is by consuming less goods and services. Decreasing the consumption of goods and services results in a lower demand, and lower supply (production) follows.[17] Individuals can prioritize shrinking the consumption of those goods and services whose production results in relatively high pollution levels. Individuals can also prioritize discontinuing the use of those goods and services that offer little to no real utility, since they neither satisfy consumer wants/needs nor the environment's.

National Geographic has concluded that city dwellers can help with climate change if they (or we) simply "buy less stuff."[115]

Lloyd Alter suggests that one way to get a practical sense of embodied carbon is to ask, "How much does your household weigh?"[116]

For-profit companies usually promote and market their products as useful or needed to potential consumers, even when they in reality are harmful or wasteful to them and/or the environment. Individuals should be diligent in self-assessing and/or researching whether or not each product they purchase and consume is really of value to decrease consumption.

Hot water consumption[]

Domestic heated water using non-renewable resources such as gas contributes to significant global Carbon Dioxide emissions and reduces carbon pool reserves.[117] Turning off the water heater and using unheated water for laundry, bathing (weather permitting), dishes, and cleaning eliminates those emissions. Besides being good for decreasing emissions, colder water is healthier than heated water, since heated water releases more lead from pipes than cold water.[118] Cold showers are also seen to have benefits over warm/hot showers.[119][120]

Culinary[]

Using reusable containers such as lunchboxes, grocery bags, produce bags, tupperware, and buying fresh produce and unpackaged foods reduces carbon emissions and pollution from the production of single use containers and packaging.[121][122]

Switching pension and investments[]

Switching pensions, insurance and investments has been suggested.[123]

Individual purchase of carbon offsets[]

The principle of carbon offset is this: one decides that they do not want to be responsible for accelerating climate change, and they have already made efforts to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions, so they decide to pay someone else to further reduce their net emissions by planting trees or by taking up low-carbon technologies. Every unit of carbon that is absorbed by trees—or not emitted due to one's funding of renewable energy deployment—offsets the emissions from their fossil fuel use. In many cases, funding of renewable energy, energy efficiency, or tree planting — particularly in developing nations—can be a relatively cheap way of making an individual "carbon neutral".[citation needed]

Political advocacy[]

Will Grant of the Pachamama Alliance describes "Four Levels of Action" for change:

- Individual

- Friends and family

- Community and institutions

- Economy and policy

Grant suggests that individuals can have the largest personal impact on climate by focusing on levels 2 and 3.[124][125]

Others posit that individual citizen participation in groups advocating for collective action in the form of political solutions, such as carbon pricing, meat pricing,[126] ending subsidies for fossil fuels[127] and animal husbandry,[128] and ending laws mandating car use,[129] is the most impactful way that an individual can take action to prevent climate change.[130]

One Fast Company article notes that "Focusing on how individuals can stop climate change is very convenient for corporations," and calls for holding industries and governments accountable on climate.[131]

It has been argued that climate change is a collective action problem, specifically a tragedy of the commons, which is a political[132] and not individual category of problem.[133]

Speaking to management about workplace emissions has been suggested.[134]

Activist movements[]

Political figures have a vested interest in remaining on the good side of the public.[clarification needed] This is because in democratic countries the public are the ones electing these government officials. Thus keeping up with protests is a way they can ensure they have the public's wants in mind.[135] Climate change is a prevalent issue in many societies.[136] Some[who?] believe that some of the long-term negative effects of climate change can be ameliorated through individual and community actions to reduce resource consumption. Thus, many environmental advocacy organizations associated with the climate movement (such as the Earth Day Network) focus on encouraging such individual conservation and grassroots organizing around environmental issues.[137][138]

Many environmental, economic, and social issues find common ground in mitigation of global warming.[139][140][clarification needed] Citizens' Climate Lobby provides climate change solutions through bipartisan and national policy which aims to set a price on carbon at the national level. With more than 500 local volunteer Chapters, the organization is building support in Congress for a national bipartisan solution to climate change.

To raise awareness of climate issues, activists organized a series of international labor and school strikes in late September 2019,[141] with estimates of total participants ranging between 6 and 7.3 million.[142][143]

A number of groups from around the world have come together to work on the issue of global warming. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from diverse fields of work have united on this issue. A coalition of 50 NGOs called Stop Climate Chaos launched in Britain in 2005 to highlight the issue of climate change.

The Campaign against Climate Change was created to focus purely on the issue of climate change and to pressure governments into action by building a protest movement of sufficient magnitude to effect political change.

Critical Mass is an event typically held on the last Friday of every month in various cities around the world wherein bicyclists and, less frequently, unicyclists, skateboarders, inline skaters, roller skaters and other self-propelled commuters take to the streets en masse. While the ride was founded in San Francisco with the idea of drawing attention to how unfriendly the city was to bicyclists, the leaderless structure of Critical Mass makes it impossible to assign it any one specific goal. In fact, the purpose of Critical Mass is not formalized beyond the direct action of meeting at a set location and time and traveling as a group through city or town streets.

One of the elements of the Occupy movement is global warming action.

Following environmentalist Bill McKibben's mantra that "if it's wrong to wreck the climate, it's wrong to profit from that wreckage,[144]" fossil fuel divestment campaigns attempt to get public institutions, such as universities and churches, to remove investment assets from fossil fuel companies. By December 2016, a total of 688 institutions and over 58,000 individuals representing $5.5 trillion in assets worldwide had been divested from fossil fuels.[145][146]

Groups such as NextGen America and Climate Hawks Vote are working in the United States to elect officials who will make action on climate change a high priority.

On 20 July 2020, Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, who was awarded a Portuguese rights award, pledged to donate the Gulbenkian Prize money of 1 million euros to organizations focused on the environment and climate change.[147]

Reform of subsidies and taxes discouraging individual action[]

Fossil fuel and other subsidies, and taxes which discourage individual action include:

- India is considering abolishing its subsidy of kerosene, which discourages individuals switching to other fuels[148]

- The UK CCC has advised cutting farm subsidies for livestock, which discourage individuals shifting to a plant based diet:[149]

- The UK CCC has advised rebalancing the taxes and regulatory costs, which are currently higher for electricity than gas and thus discourage individuals from switching from gas boilers to heat pumps[149]

- Turkey's free coal for poor families[150] discourages them switching to natural gas in cities.

- Redirecting the money which would have been spent as subsidies, together with any carbon tax, to form a carbon dividend in equal shares for everyone or for poor people has been suggested by the International Monetary Fund and others to encourage individuals to take action as part of a just transition away from a high carbon lifestyle.[151]

However, sudden removal of a subsidy by governments not trusted to redirect it,[152] or without providing good alternatives for individuals, can lead to civil unrest. An example of this took place in 2019, when Ecuador removed its gasoline and diesel subsidies without providing enough electric buses to maintain service. The result was overnight fuel price hikes of 25-75 percent. The corresponding fare hikes for Ecuador's existing gas and diesel powered bus fleet were met with violent protests.[153]

Lack of information, or misleading information on individual actions[]

As recently as 2008, "about 40% of adults worldwide ... [had] never heard of climate change, or nearly 2 billion people."[154]

Focus on climate change effects, without information on taking action[]

Climate change education, which became mandatory in Italy in 2019,[155] is completely absent in some countries, or fails to provide information on action that individuals can take.

In some countries media coverage of global warming reports the effects of climate change, such as extreme weather, but makes no mention of either individual or government actions which can be taken.[156]

Presenting plant based diets as strict vegetarianism[]

The suggestion that eating a plant based diet requires a person to become strictly vegetarian is also misinformation.[157] A plant-based diet focuses on consuming foods primarily from plants. Some examples of food consumed in a plant-based diet are fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, oils, whole grains, legumes, and beans. People may consider it as being vegan or vegetarian but it is very different. Vegan diets eliminate all animal products, meanwhile, plant-based diets do not completely eliminate animal products, but they encourage the focus on eating mostly plants. One downside of having a plant-based diet is that plant-based diets carry some risk of inadequate protein and mineral intake. But, according to the Physicians Committee,[158] you can choose the right plant-based food to overcome the risk "Plant-based foods are full of fiber, rich in vitamins and minerals, free of cholesterol, and low in calories and saturated fat".[158]

Impact of individual actions[]

Media focus on low impact rather than high impact behaviors is concerning for scientists. The most impactful actions for individuals may differ significantly from the popular advice for "greening" one's lifestyle. For instance, popular suggestions for individual actions include:

- Replacing a typical car with a hybrid (0.52 tonnes);

- washing clothes in cold water (0.25 tonnes);

- recycling (0.21 tonnes);

- upgrading light bulbs (0.10 tonnes); etc. -- all lower impact behaviors.

- switching bank accounts to a greener bank.

Researchers have stated that "Our recommended high-impact actions:

- one fewer child,

- living car-free

- avoiding one trans-Atlantic flight

- eating a plant-based diet

are more effective than many more commonly discussed options. For example, eating a plant-based diet saves eight times more emissions than upgrading light bulbs."[8][9] Public discourse on reducing one's carbon footprint overwhelmingly focuses on low-impact behaviors, and as of 2017, the mention of high-impact individual behaviors to impact climate was almost non-existent in mainstream media, government publications, K-12 school textbooks, etc.[8][9]

However, advocate Bill McKibben is joined by many others in his opinion that "no effort is too small" with regards to climate change.[159][160][161][162][163]

Climate conversations[]

"Discussing global warming leads to greater acceptance of climate science," according to a 2019 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[164] The Yale Climate Communication Program recommends initiating "climate conversations" with more moderate individuals.[165][56] Patient listening is key, to determine the personal impacts of climate events on an individual, and to elicit information about the other person's core values.[166] Once personal climate impacts and core values are understood, it may become possible to open a discussion of potential climate solutions which are consistent with those core values.[165][167]

Carbon Conversations is a "psychosocial project that addresses the practicalities of carbon reduction while taking account of the complex emotions and social pressures that make this difficult".[168] The project touches on five main topics: i) home energy; ii) food; iii) travel; iv) consumption and waste; and v) talking with family and friends. The project understands that individuals often fail to adopt low-carbon lifestyles not because of practical barriers to change (e.g.: there is no renewable energy available), but because of aspects related to their values, emotions, and identity. The project offers a supportive group experience that helps people reduce their personal carbon dioxide emissions by 1 tonne CO

2 on average and aim at halving it in the long term. They deal with the difficulties of change by connecting to values, emotions and identity. The groups are based on a psychosocial understanding of how people change. Groups of 6-8 members meet six or twelve times with trained facilitators in homes, community centres, workplaces or other venues. The meetings create a non-judgmental atmosphere where people are encouraged to make serious lifestyle changes.

Carbon Conversations was cited in The Guardian newspaper as one of the 20 best ideas to tackle climate change.[169]

See also[]

- Anthropization

- Bill McKibben

- Carbon diet

- Climate change mitigation

- Fossil fuel divestment

- Individual and political action on climate change

- International Day of Climate Action

- Low-carbon diet

- Low-carbon economy

- No Impact Man (Colin Beavan)

- One Watt Initiative

- Personal carbon credits

- Plant-based diet

- Reducing air travel

- Veganism

- Voluntary childlessness

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carbon targets for your footprint". shrinkthatfootprint.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ "İklim korumada en önemli beş adım | DW | 15.02.2019". DW.COM (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ Reality, Better Meets (2019-02-03). "What Is A Sustainable Carbon Footprint (Per Person) To Aim For?". Better Meets Reality. Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "What exactly is a tonne of CO2?". Energuide. Archived from the original on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ Edenhofer, Ottmar; Pichs-Madruga, Ramón; et al. (2014). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). In IPCC (ed.). Climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-65481-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ^ "Emissions inequality—a gulf between global rich and poor – Nicholas Beuret". Social Europe. 2019-04-10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- ^ Westlake, Steve. "Climate change: yes, your individual action does make a difference". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2019-12-18. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Wynes, Seth; Nicholas, Kimberly A (12 July 2017). "The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (7): 074024. Bibcode:2017ERL....12g4024W. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541.

We recommend four widely applicable high-impact (i.e. low emissions) actions with the potential to contribute to systemic change and substantially reduce annual personal emissions: having one fewer child (an average for developed countries of 58.6 tonnes CO2-equivalent (tCO2e) emission reductions per year), living car-free (2.4 tCO2e saved per year), avoiding airplane travel (1.6 tCO2e saved per roundtrip transatlantic flight) and eating a plant-based diet (0.8 tCO2e saved per year). These actions have much greater potential to reduce emissions than commonly promoted strategies like comprehensive recycling (four times less effective than a plant-based diet) or changing household lightbulbs (eight times less).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Perkins, Sid (July 11, 2017). "The best way to reduce your carbon footprint is one the government isn't telling you about". Science. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". the Guardian. 2018-05-31. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Lukacs, Martin (July 17, 2017). "Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Tallulah, Tegan (2018-01-10). "Individual vs Collective: Are you Responsible for Fixing Climate Change?". Resilience. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Valle, Gaby Del (2018-10-12). "Can individual consumer choices ward off the worst effects of climate change? It's complicated". Vox. Archived from the original on 2019-12-29. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Kaufman, Mark (13 July 2020). "The devious fossil fuel propaganda we all use". Mashable. Archived from the original on 2020-09-17. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- ^ Hagmann, David, Emily H Ho, und George Loewenstein. 2019. „Nudging out Support for a Carbon Tax“. Nature Climate Change 9(6): 484–89.

- ^ Sparkman, Leor Hackel, Gregg (2018-10-26). "Actually, Your Personal Choices Do Make a Difference in Climate Change". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Publisher, Author removed at request of original (2016-06-17), "3.3 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium", Principles of Economics, University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2012 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution., archived from the original on 2021-01-12, retrieved 2020-12-30

- ^ "Emissions Gap Report 2020 / Executive Summary" (PDF). UNEP.org. Fig. ES.8: United Nations Environment Programme. 2021. p. XV. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2021.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ "In-depth Q&A: The IPCC's sixth assessment report on climate science". Carbon Brief. 2021-08-09. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "EDGAR - Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries, 2019 report - European Commission". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (2020-05-20). "Top 10 tips for combating climate change revealed". BBC. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Akenji, Lewis; Lettenmeier, Michael; Koide, Ryu; Toivio, Viivi; Amellina, Aryanie (2019). 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and options for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Aalto University, and D-mat ltd. ISBN 978-4-88788-220-1.

- ^ "India urges G20 nations to bring down per capita emissions by '30". Hindustan Times. 2021-07-25. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "France: CO2 emissions 1970-2020". Statista. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "5 charts show how your household drives up global greenhouse gas emissions". PBS NewsHour. 2019-09-21. Archived from the original on 2020-01-15. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (2020-03-16). "The rich are to blame for climate change". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ^ "World's richest 10% produce half of carbon emissions while poorest 3.5 billion account for just a tenth". 2 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (April 13, 2021). "World's wealthiest 'at heart of climate problem'". BBC. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "REDUCING YOUR CARBON FOOTPRINT CAN BE GOOD FOR YOUR HEALTH" (PDF).

- ^ "Emissions Gap Report 2020: chapter 6: Bridging the gap – the role of equitable low-carbon lifestyles" (PDF).

- ^ Heinonen, Jukka; Ottelin, Juudit; Ala-Mantila, Sanna; Wiedmann, Thomas; Clarke, Jack; Junnila, Seppo (2020-05-20). "Spatial consumption-based carbon footprint assessments - A review of recent developments in the field". Journal of Cleaner Production. 256: 120335. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120335. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; et al. (13 November 2017), "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice" (PDF), BioScience, 67 (12): 1026–1028, doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125, archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2019, retrieved 29 March 2019

- ^ Conly, Sarah (2016). One child : do we have a right to more?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020343-6.

- ^ "Bioethicist: The climate crisis calls for fewer children". Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "We need to talk about the ethics of having children in a warming world". 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Want to fight climate change? Have fewer children". 12 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Population Matters: Climate change". 16 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Bawden, Tom (April 26, 2019). "Save the planet by having fewer children, says environmentalist Sir Jonathan Porritt". i. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew; Leong, Kit Ling (2020-11-01). "Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change". Climatic Change. 163 (2): 1007–1023. Bibcode:2020ClCh..163.1007S. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02923-y. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 226983864.

- ^ Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew (2021-03-28). "The environmental politics of reproductive choices in the age of climate change". Environmental Politics. 0: 1–21. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1902700. ISSN 0964-4016. S2CID 233666068.

- ^ Wynes and Nicholas Supplementary Materials 5 (2017).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murtaugh, Paul A.; Schlax, Michael G. (2009-02-01). "Reproduction and the carbon legacies of individuals". Global Environmental Change. 19 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.007. ISSN 0959-3780. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- ^ Roberts, David (2017-07-14). "The best way to reduce your personal carbon emissions: don't be rich". Vox. Archived from the original on 2019-11-08. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ editor, Damian Carrington Environment (2017-07-12). "Want to fight climate change? Have fewer children". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-10-22.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Cassella, Carly (April 25, 2020). "Becoming a Parent Makes You 25% Less Environmentally Friendly, New Research Finds". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Family Planning". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-08-31. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ "Educating Girls". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R (November 5, 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (November 5, 2019). "Climate crisis: 11,000 scientists warn of 'untold suffering'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ Handy, Susan; Weston, Lisa; Mokhtarian, Patricia L. (2005-02-01). "Driving by choice or necessity?". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 39 (2–3): 183–203. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.09.002. ISSN 0965-8564.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Butt, Sarah; Shaw, Andrew (2009), "Pay More, Fly Less? Changing Attitudes to Air Travel", British Social Attitudes: The 25th Report, London: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 129–154, doi:10.4135/9780857024350.n6, ISBN 978-1-84860-639-5, retrieved 2021-05-15

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hawkins, Troy R.; Gausen, Ola Moa; Strømman, Anders Hammer (2012-09-01). "Environmental impacts of hybrid and electric vehicles—a review". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 17 (8): 997–1014. doi:10.1007/s11367-012-0440-9. ISSN 1614-7502. S2CID 109391241.

- ^ "Factcheck: How electric vehicles help to tackle climate change". Carbon Brief. 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-09-11). "What You Can Do to Reduce Pollution from Vehicles and Engines". US EPA. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ Shaheen, Susan; Cohen, Adam; Bayen, Alexandre (2018-10-22). "The Benefits of Carpooling". doi:10.7922/G2DZ06GF. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Anair, Don, Jeremy Martin, Maria Cecilia Pinto de Moura, and Joshua Goldman. 2020. Ride-Hailing’s Climate Risks: Steering a Growing Industry toward a Clean Transportation Future. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

- ^ Baptista, Patrícia; Melo, Sandra; Rolim, Catarina (2014-02-05). "Energy, Environmental and Mobility Impacts of Car-sharing Systems. Empirical Results from Lisbon, Portugal". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 111: 28–37. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.035. ISSN 1877-0428.

- ^ Yang, Yong (2015-06-01). "Interactions between psychological and environmental characteristics and their impacts on walking". Journal of Transport & Health. 2 (2): 195–198. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2014.11.003. ISSN 2214-1405. PMC 4480794. PMID 26120558.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zhang, Yongping; Mi, Zhifu (2018-06-15). "Environmental benefits of bike sharing: A big data-based analysis". Applied Energy. 220: 296–301. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.03.101. ISSN 0306-2619.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nesheli, Mahmood Mahmoodi; Ceder, Avishai (Avi); Ghavamirad, Farzan; Thacker, Scott (2017-03-01). "Environmental impacts of public transport systems using real-time control method". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 51: 216–226. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2016.12.006. ISSN 1361-9209.

- ^ "Is 'green' the new black?". Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ^ "Which form of transport has the smallest carbon footprint?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Slotnick, David. "Airlines are working to cut down on emissions to secure their future business model, but the technology to make a real impact is still years away". Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ "Behaviour change, public engagement and Net Zero (Imperial College London)". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Seven charts that explain what net zero emissions means for the UK". www.newscientist.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Carbon offsetting flights. A dangerous distraction. Helping Dreamers Do". responsibletravel.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-18. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "Air travel and climate change". David Suzuki Foundation. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Sustainable Mobility: Are Electric Scooters Eco-Friendly?". Youmatter. 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ Ortiz, Diego Arguedas (4 November 2018). "Ten simple ways to act on climate change". BBC Future. Archived from the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Moskin, Julia; Plumer, Brad; Lieberman, Rebecca; Weingart, Eden; Popovich, Nadja (2019-04-30). "Your Questions About Food and Climate Change, Answered (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R (November 5, 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278.

- ^ Briggs, Nassos Stylianou, Clara Guibourg and Helen (2018-12-13). "Climate change food calculator: What's your diet's carbon footprint?". Archived from the original on 2019-10-12. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ Gallagher, James (2019-01-17). "Meat, veg, nuts - a diet designed to feed 10bn". Archived from the original on 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- ^ "Healthy diet". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (August 8, 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ "Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies". Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Publishing, Harvard Health (June 2012). "Cutting red meat-for a longer life". Harvard Health. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Plant-Rich Diet". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-11-20. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Chodosh, Sara (March 21, 2018). "One-fifth of Americans are responsible for half the country's food-based emissions". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Heller, Martin C.; Willits-Smith, Amelia; Meyer, Robert; Keoleian, Gregory A.; Rose, Donald (March 2018). "Greenhouse gas emissions and energy use associated with production of individual self-selected US diets". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (4): 044004. Bibcode:2018ERL....13d4004H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aab0ac. ISSN 1748-9326. PMC 5964346. PMID 29853988.

- ^ "Guide to Solar-Reflective Paints for Energy-Efficient Homes". Educational Community for Homeowners (ECHO). 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Using energy more efficiently". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ "Behaviour change, public engagement and Net Zero (Imperial College London)". Committee on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ "What is green gas? – Ecotricity". www.ecotricity.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ "Rooftop Solar". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "2019 Most Energy Efficient Appliances | EnergySage". www.energysage.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "The International EPD® System". www.environdec.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Our Story". Trees for the Future. Archived from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ "Lawns may contribute to global warming". Christian Science Monitor. 2010-01-22. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Townsend‐Small, Amy; Czimczik, Claudia I. (2010). "Carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions in urban turf". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (2): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..37.2707T. doi:10.1029/2009GL041675. ISSN 1944-8007. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Fountain, Henry; Kaysen, Ronda (2019-04-10). "One Thing You Can Do: Reduce Your Lawn". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-09-15. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Tucker, Acadia (October 2019). Growing good food : a citizen's guide to backyard carbon farming. San Francisco, California. ISBN 978-0-9988623-3-0. OCLC 1031904257.

- ^ Toensmeier, Eric (2016). The carbon farming solution : a global toolkit of perennial crops and regenerative agriculture practices for climate change mitigation and food security. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60358-571-2. OCLC 920450914.

- ^ Fryling, Kevin (2019-01-22). "IU study predicts air pollutant increase from U.S. forest soils". News at IU. Archived from the original on 2019-01-27. Retrieved 2019-01-27.. In the Eastern US, maples, sassafrass, and tulip poplar, which are associated with ammonia-oxidizing bacteria known to "emit reactive nitrogen from soil," push out the beneficial oak, beech, and hickory, which are associated with microbes that "absorb reactive nitrogen oxides.

- ^ Bowe, Alice. (2011). High-impact, low-carbon gardening : 1001 ways to garden sustainably. Portland, Or.: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-998-0. OCLC 666223945.

- ^ Cotton, Lucy; Hayward, Adam S.; Lant, Neil J.; Blackburn, Richard S. (2020). "Improved garment longevity and reduced microfibre release are important sustainability benefits of laundering in colder and quicker washing machine cycles". Dyes and Pigments. 177: 108120. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.108120.

- ^ Berners-Lee, Mike; Clark, Duncan (2010-11-25). "What's the carbon footprint of … a load of laundry?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "The Benefits of Using a Clothesline". Small Footprint Family™. 2009-08-10. Archived from the original on 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (2010-10-08). "High and dry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Hughes, Kathleen A. (2007-04-12). "To Fight Global Warming, Some Hang a Clothesline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Hurst, Nathan. "What's the Environmental Footprint of a T-Shirt?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "The price of fast fashion". Nature Climate Change. 8 (1): 1. January 2018. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8....1.. doi:10.1038/s41558-017-0058-9. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ Feather, Katie. "How The Fashion Industry Is Responding To Climate Change". Science Friday. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Copyright © 2020. "Lessening the Harmful Environmental Effects of the Clothing Industry". Planet Aid, Inc. Archived from the original on 2019-02-04. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Roth, Sammy (2019-04-04). "California's next frontier in fighting climate change: your kitchen stove". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Clean Cooking Alliance". Clean Cooking Alliance. Archived from the original on 2019-01-06. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Wood Burning and Our Climate". Doctors and Scientists Against Wood Smoke Pollution. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Home". Solar Cookers International. Archived from the original on 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Rocha, Ian De La (2019-11-01). "Solar Cookers: How They Can Provide Food Access Across the World - Solstice™ Community Solar". Solstice™ Community Solar. Archived from the original on 2020-09-29. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Otte, Pia. "Relevant factors for the successful adoption of institutional solar" (PDF). Solar Cookers.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "How Cooking with Solar Power in China Decreases Air Pollution and Empowers Women". The MetLife Blog. April 22, 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Singh, Madhur (2008-07-07). "India's Temples Go Green". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Deshp, Chaitanya (May 21, 2016). "Shirdi Sai temple gets excellence award for solar kitchen". Nashik News - The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2020-03-25. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Bitcoin emits as much carbon as Las Vegas, researchers say". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-21. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Borunda, Alejandra (2019-06-11). "How can city dwellers help with climate change? Buy less stuff". National Geographic - Environment. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Alter, Lloyd (October 18, 2018). "How much does your household weigh?". TreeHugger. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Reduced Carbon Footprint from Solar Hot Water for your Home or Business | New England Solar Hot Water". www.neshw.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ "Let it run...and get the lead out! Fact Sheet - EH: Minnesota Department of Health". www.health.state.mn.us. Archived from the original on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ Shevchuk, Nikolai A. (2008-01-01). "Adapted cold shower as a potential treatment for depression". Medical Hypotheses. 70 (5): 995–1001. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.04.052. ISSN 0306-9877. PMID 17993252. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ Buijze, Geert A.; Sierevelt, Inger N.; Heijden, Bas C. J. M. van der; Dijkgraaf, Marcel G.; Frings-Dresen, Monique H. W. (2016-09-15). "The Effect of Cold Showering on Health and Work: A Randomized Controlled Trial". PLOS ONE. 11 (9): e0161749. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161749B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161749. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5025014. PMID 27631616.

- ^ Xanthos, Dirk; Walker, Tony R. (2017-05-15). "International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 118 (1–2): 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.02.048. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 28238328. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ Schnurr, Riley E. J.; Alboiu, Vanessa; Chaudhary, Meenakshi; Corbett, Roan A.; Quanz, Meaghan E.; Sankar, Karthikeshwar; Srain, Harveer S.; Thavarajah, Venukasan; Xanthos, Dirk; Walker, Tony R. (2018-12-01). "Reducing marine pollution from single-use plastics (SUPs): A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 137: 157–171. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.001. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 30503422. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ "What can I do about climate change? How to shrink your carbon footprint". Positive News. 2021-08-10. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ Will Grant Four Levels of Action, archived from the original on 2020-08-01, retrieved 2019-09-28

- ^ "The Drawdown Project to Reverse Global Warming — Educational Resources". Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter. April 29, 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Gabbatiss, Josh (January 4, 2019). "Government must consider meat tax to tackle climate change, says Caroline Lucas". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Irfan, Umair (May 17, 2019). "whopping $5.2 trillion: We can't take on climate change without properly pricing coal, oil, and natural gas. But it's a huge political challenge". Vox. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Simon, David Robinson (September 1, 2013). Meatonomics: How the Rigged Economics of Meat and Dairy Make You Consume Too Much–and How to Eat Better, Live Longer, and Spend Smarter. U.S.A.: Conari Press. ISBN 978-1573246200.

- ^ Shill, Gregory (July 9, 2019). "Americans Shouldn't Have to Drive, but the Law Insists on It: The automobile took over because the legal system helped squeeze out the alternatives". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Stern, Stefan (June 21, 2019). "Politicians must find solutions for the climate crisis. Not outsource it to us". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Byskov, Morten Fibieger (2019-01-11). "Focusing on how individuals can stop climate change is very convenient for corporations". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ Anomaly, Jonathan. "Political: Collective Action Problems". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Kejun, Jiang (December 14, 2018). "Climate change is a problem of politics, not science". Euractiv. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Climate crisis: what can I do from the UK to help save the planet?". the Guardian. 2021-08-10. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ Ruud Woutersa, Stefaan Walgrave (2017). "Demonstrating Power: How Protest Persuades Political Representatives" (PDF). American Sociological Review. doi:10.1177/0003122417690325. S2CID 151824503 – via American Sociological Association.

- ^ "A look at how people around the world view climate change". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ "Act on Climate Change". Climate Generation: A Will Steger Legacy. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ "About Us". Earth Day Network. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- ^ "Sustainable Development: Linking economy, society, environment". oecd.org. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Exchanges?, Comments and Reply. "Weather, Climate, and Society". American Meteorological Society.

- ^ "Global Climate Strike → A Historic Week". Global Climate Strike → Sep. 20–27. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew; Watts, Jonathan; Bartlett, John (27 September 2019). "Climate crisis: 6 million people join latest wave of global protests". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ "Global climate strike gathers 7.6m people". Hürriyet Daily News. 29 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "The Case for Fossil-Fuel Divestment". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "Commitments". Fossil Free. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (2016-12-12). "Fossil fuel divestment funds double to $5tn in a year". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "Greta Thunberg donates million-euro rights prize to green groups". France 24. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Jacob, Shine (2019-10-06). "Subsidy on kerosene may go by FY21 as fuel consumption shifts to LPG". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rowlatt, Justin (2019-10-11). "'Only big changes' will tackle climate change". Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "HOW TO DELIVER FREE COAL TO THE POOR FAMILIES? TURKEY CASE". Archived from the original on 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Elliott, Larry (2019-10-10). "Energy bills will have to rise sharply to avoid climate crisis, says IMF". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "Here's why raising gas prices leads to violent protests like Ecuador's". Archived from the original on 2019-10-14.

- ^ "How not to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies". The Ecologist. Archived from the original on 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Leiserowitz, Anthony (2015-10-29). "Nearly 2 Billion Adults Have Never Heard of Climate Change". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Bentson, Clark (November 7, 2019). "Italy makes climate change education compulsory". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Climate change triggers extreme weather in Turkey". DailySabah. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-10-01. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ "Myths and Misconceptions About Plant-Based Diets". National Kidney Foundation. 2018-08-18. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Plant-Based Diets". Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Solutions". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Wilkinson, Katharine (April 23, 2018). "Solving Climate Change: A Blueprint. Project Drawdown". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ McCartney, Paul (2017-11-27). "Climate change is a real issue and no effort is too small when it comes to protecting and preserving our planet". @paulmccartney. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Scanlon, Colleen (2018-07-10). "Through environmental stewardship, hospitals can preserve and protect health". GreenBiz. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ McAlpine, Sara; Murray, Daisy (2019-02-01). "Sustainable Style Tips From The Influencers That Know Best". ELLE. Archived from the original on 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Goldberg, Matthew (July 9, 2019). "Discussing global warming leads to greater acceptance of climate science". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (30): 14804–14805. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11614804G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1906589116. PMC 6660749. PMID 31285333. Archived from the original on 2019-11-16. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kirk, Karin (2018-04-03). "Finding common ground amid climate controversy". Yale Climate Connections. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Evich, Helena Bottemiller (December 9, 2019). "How a closed-door meeting shows farmers are waking up on climate change". Politico. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Attaining Meaningful Outcomes from Conversations on Climate". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 2019-11-26. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "About". Carbon Conversations. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- ^ Katz, Ian (2009). Twenty Ideas That Could Save the World

Notes[]

- ^ Japan, Russia and USA only[41]

- ^ Wynes and Nicholls have done a calculation (not specified in either paper but not complicated); inputs to their calculation include the results calculated by Murtaugh and Schlax in their scenario which assumes 1) per capita emissions from each country remain at 2005 levels 2) UN "medium variant" 2007 fertility estimate. By projecting an unspecified number of years into the future Murtaugh and Schlax have estimated the emissions of a person born in 2005 and half their children, quarter grandchildren etc. as USA 9441 tonnes, Russia 2498, Japan 2026.[42]

External links[]

- 52 Climate Actions themed suggestions for personal actions.

- Air travel, climate change, and green consumerism at Appropedia

- What we all can do at Climatesafety.info

- Carrington, Damian (May 31, 2018). "Avoiding meat and dairy is 'single biggest way' to reduce your impact on Earth". The Guardian.

- Lack, Bella (April 26, 2019). "Our fight against climate change will be hopeless unless we choose to have smaller families". The Telegraph.

- "Climate change food calculator: What's your diet's carbon footprint?". BBC.

- Climate change policy

- Environmental ethics

- Climate change and society

- Politics of climate change