Collingwood, Victoria

| Collingwood Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Robert Burns Hotel on Smith Street | |||||||||||||||

Collingwood | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′07″S 144°59′17″E / 37.8019°S 144.98815°ECoordinates: 37°48′07″S 144°59′17″E / 37.8019°S 144.98815°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 8,513 (2016)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 7,217/km2 (18,690/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1850s | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3066 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 1.3 km2 (0.5 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Yarra | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Richmond | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

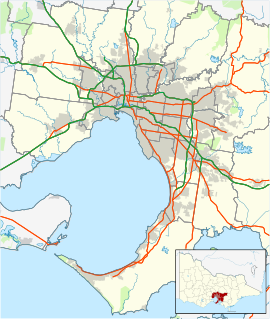

Collingwood is an inner-city suburb of Melbourne, Australia, 3 km north-east of Melbourne's central business district. Its local government area is the City of Yarra. At the 2016 Australian Census, Collingwood had a population of 8,513.[1]

Collingwood is one of the oldest suburbs in Melbourne and is bordered by Smith Street, Alexandra Parade, Hoddle Street and Victoria Parade.

Collingwood is notable for its historical buildings, with many nineteenth century dwellings, shops and factories still in use. Its major thoroughfare Smith Street is one of Melbourne's major nightlife and retail strips.

It was named in 1842 after Baron Collingwood or an early hotel which bore his name.[2][3]

History[]

Toponomy[]

It was 'named after' Lord Horatio Nelson's 'favourite admiral' Baron Collingwood (or, possibly after the Collingwood Hotel which existed there and was named after the admiral) by surveyor Robert Hoddle, under instructions from Superintendent Charles La Trobe, in 1842.[2][3]

Australian author Frank Hardy set the novel Power Without Glory in a fictionalised version of the suburb, named Carringbush.[4] The name is used by a number of businesses in the area, such as "Carringbush Business Centre". At one time a ward in the City of Yarra that includes part of Collingwood was actually named Carringbush.

Establishment[]

Subdivision and sale of land in Collingwood began in 1838, and was mostly complete by the 1850s. Collingwood was declared a municipality, separate from the City of Melbourne on 24 April 1855, the first to follow the state's major population centres of Melbourne and Geelong.[5] Collingwood was proclaimed a town in 1873, and later a city in 1876.[6]

Collingwood's early development was directly impacted by the boom in Melbourne's population and economy during the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s and 1860s. This resulted in the construction of a large number of small dwellings, as well as schools, shops and churches to support this new population. Around the same time, large industrial developments such as a flour mill and the Fosters brewery were being established.

19th and 20th centuries[]

In the 1870s, Smith Street became the dominant shopping strip, with its tram line established in 1887. Many of Collingwood's grand public buildings were erected in the 1880s, including the post office and town hall. Collingwood also had a strong temperance movement, with two "coffee palaces" springing up in the 1870s, including the large and grand Collingwood Coffee Palace (now the facade of Woolworths – minus original classical pediment and mansard).

At the turn of the century Collingwood's Smith Street rivalled Chapel Street in Prahran as the dominant home of suburban emporiums and department stores. The first G.J. Coles store was opened in the street in 1912.

Since the 1950s, Collingwood has been home to many groups battling to save the suburb's unique character against development and gentrification.

In 1958 residents rallied at Collingwood Town Hall against the Housing Commission of Victoria's slum reclamation projects, which would see demolition orders for 122 of the suburb's homes.[7]

In the 1970s, 150 residents protested against plans for the F-19 freeway,[8] with some putting themselves in front of earthmovers during the construction.[9]

The Collingwood Action Group formed in 2006 to fight the "Banco" development, a large mixed use project on Smith Street.[10]

Recent history[]

In 2010, over 2,000 people rallied to save The Tote Hotel, a popular live music venue, which became a potential state election issue.[11]

In 2016, the Bendigo street housing campaign began in northeast Collingwood, in which the community took control of up to 15 empty state government owned houses, in an attempt to provide housing for Melbourne's rising homeless population, in the absence of adequate public housing.

Geography[]

Collingwood's topography is mostly flat, but a prominent slope extends from Hoddle Street up to Smith Street, and also along sections of Hoddle Street.[citation needed]

The suburb is notable for its historical buildings, with many nineteenth century dwellings, shops and factories still in use. From its early days large commercial buildings often coexisted with small dwellings, occupied by working-class families and the mixture of industry and community continues to the present time. For example, Oxford and Cambridge Streets are dominated by imposing red-brick factories and warehouses, formerly occupied by the Foy and Gibson company, but also feature a number of stone, brick and timber dwellings that date back to the earliest days of the suburb.

Culture[]

Sport[]

The Collingwood Football Club (the Magpies) has a history dating back to 1892 as an incorporated football club. They were once housed at Victoria Park and are now based at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG).

In recent years they won the 2010 grand final rematch against St Kilda. They have won 15 VFL/AFL premierships, which is the second most in the league behind Carlton and Essendon, and also won the 1896 VFA premiership.

Community radio[]

3CR is an independent community radio station that is located at the Victoria Parade end of Smith St. The station has been based in the suburb since 1977 and its frequency is 855AM.[12]

PBS 106.7FM relocated from St Kilda to Collingwood and is located at 47 Easey Street. PBS is a community radio station that celebrated its 25th year of broadcasting in 2004.

Economy[]

Jetstar and Madman Entertainment have head offices in Collingwood.[13][14]

Commercial areas[]

The main commercial area is Smith Street, which borders Fitzroy. In 2021, Smith Street was named the coolest street in the world.[15][16][17][18]

Gay village[]

Collingwood is one of Melbourne's gay villages with several gay oriented entertainment venues.[19] These include the Peel Dancebar which, in 2007, was granted the legal right to ban heterosexual patrons from the bar.[20][21][22] By November 2019, sex on premises venue Club 80 had operated in Collingwood for over twenty years.[23]

Education[]

Collingwood Technical School was established in July 1912 as a trades and technical training school. The school closed in 1987 and, forming along with the Preston Technical School, was the basis for the formation of the Northern Melbourne Institute of TAFE, which continues to have a Collingwood campus in Otter Street.

Collingwood College, a state P-12 school, is located in the suburb.

The Academy of Design Australia is located in the suburb in a repurposed building previously belonging to Foy & Gibson. The Academy offers the "Bachelor of Design Arts", a degree unique to the state of Victoria.

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 5,081 | — |

| 2006 | 5,493 | +8.1% |

| 2011 | 6,467 | +17.7% |

| 2016 | 8,513 | +31.6% |

In the 2016 Census, there were 8,513 people in Collingwood. 51.9% of people were born in Australia. The next most common countries of birth were Vietnam 4.0%, England 3.8%, New Zealand 3.5%, China 2.6% and Ethiopia 1.4%. 60.4% of people spoke only English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Vietnamese 5.3%, Mandarin 3.1%, Cantonese 1.7%, Somali 1.6% and Greek 1.6%. The most common response for religion was No Religion at 46.8%.[1]

Housing[]

Collingwood's housing consists of a large number of high-rise housing commission flats and a number of older single and double storey former workers cottages on small subdivisions.

More recently older warehouses and factories have been converted into fashionable apartments and there has been modern townhouse infill and medium density unit development.

Governance[]

The City of Collingwood existed from 1855 until 1994.

Public and commercial buildings[]

Collingwood has many buildings listed on the Victorian Heritage Register and several notable commercial and public buildings. Yorkuprhire Brewery, built in 1880 to the design of James Wood, with its polychrome brick and mansard roof tower, was once Melbourne's tallest building. For many years it has been subject to development proposals and the heritage stables were at one stage demolished without a permit, however the site remains neglected.

The former Collingwood Post Office was built between 1891 and 1892 in the Victorian Mannerist style, to the design of John Marsden and is similar to Rupertswood, with its tall tower.

Prominent hotels include the Leinster Arms Hotel, established in 1865 and is the only single storey hotel built in Melbourne in that era, the Sir Robert Peel ("The Peel") Hotel and the Vine Hotel.

The original Collingwood Magistrates' Court closed on 1 February 1985, but continued local need saw the establishment of the Neighbourhood Justice Centre court in the suburb in 2007.[24][25]

Despite its name, the Collingwood Children's Farm is in the neighbouring suburb Abbotsford.

Notable people[]

- Emma Minnie Boyd (1858–1936), artist[26]

- John Cowan Duncan (1901–1955), company manager[27]

- John Hunter Patterson (1841–1930), grazier and mining investor[28]

Transport[]

Transport within Collingwood consists mainly of narrow one-way streets. The suburb is bounded by main roads: Smith Street to the west, Victoria Parade to the south, Hoddle Street to the east and Alexandra Parade to the north. Major tramlines are on Victoria Street (tram route 109) and Smith Street (route 86), which are on the edge of the suburb. Johnston, Wellington and Langridge Streets are the main arterials going through the suburb.

The Collingwood railway station is in neighbouring Abbotsford.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Collingwood (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "VICTORIAN HISTORY". The Argus. Melbourne. 15 October 1909. p. 9. Retrieved 26 September 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barnard, Jill (25 February 2010). "Collingwood". e-Melbourne. School of Historical Studies Department of History, The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Hardy, Frank (1950) Power Without Glory, Random House.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 691.

- ^ Monash University (November 2004). "Collingwood, Victoria". Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 15 June 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ "The Age - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1300&dat=19740429&id=oxAQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=wpADAAAAIBAJ&pg=7021,6757387[dead link]

- ^ "1970s. Anti-freeway protest". www.picturevictoria.vic.gov.au. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Stark, Jill; Craig, Natalie (24 January 2010). "Spring Street tap dances, fearing the Tote could rock the vote". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ 3CR 855 AM (2012). "The 3CR story". 3CR Community Radio. 3CR 855 AM. Retrieved 1 September 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Contact Information." Madman Entertainment. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Map of the Ward Boundaries Archived 2 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine." City of Yarra. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Kelly, Cait. "Melbourne beats out Sydney, with this street named the coolest in the world". The New Daily. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Street, Francesca. "The world's 'coolest' street revealed by Time Out". CNN. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ McMah, Lauren. "Melbourne's Smith Street named coolest street in the world". news.com.au. News Corp. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Russo, Rebecca. "Smith Street has been named the coolest street in the world". Timeout. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Richard Watts (2011). "Gay & Lesbian Melbourne" (PDF). Lonely Planet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Editorial (29 May 2007). "Gay conundrum". The Herald Sun. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Gay pub defends 'straight' ban". The Age. Australian Associated Press. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Steve Dow (30 May 2007). "Don't lock out the heterosexuals". The Age. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Marc Pallisco (1 November 2019). "Collingwood home of Club 80 sold and set to make way for offices". realestatesource.com.au. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Special Report No. 4 - Court Closures in Victoria" (PDF). Auditor-General of Victoria. 1986. p. 79. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Neighbourhood Justice Centre Celebrates 10 Years". 6 March 2017. Department of Premier and Cabinet. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Tipping, Marjorie J. (1979). "Boyd, Emma Minnie (1858–1936)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Maidment, Ewan (1996). "Duncan, John Cowan (1901–1955)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Boadle, Donald (1988). "Patterson, John Hunter (1841–1930)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

External links[]

Media related to Collingwood, Victoria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Collingwood, Victoria at Wikimedia Commons- Australian Places – Collingwood

- Collingwood Historical Society

- Suburbs of Melbourne

- Gay villages in Australia

- Slums in Australia