Government of the Qing Dynasty

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic structures and institutions from the preceding Ming dynasty but split rule between Han Chinese and Manchus, with some positions also given to Mongols.[1] Like previous dynasties, the Qing recruited officials via the imperial examination system, until the system was abolished in 1905. The Qing divided the positions into civil and military positions, each having nine grades or ranks, each subdivided into a and b categories. Civil appointments ranged from an attendant to the emperor or a Grand Secretary in the Forbidden City (highest) to being a prefectural tax collector, deputy jail warden, deputy police commissioner, or tax examiner. Military appointments ranged from being a field marshal or chamberlain of the imperial bodyguard to a third class sergeant, corporal or a first or second class private.[2]

Central government agencies[]

The formal structure of the Qing government centered on the Emperor as the absolute ruler, who presided over six Boards (Ministries[a]), each headed by two presidents[b] and assisted by four vice presidents.[c] In contrast to the Ming system, however, Qing ethnic policy dictated that appointments were split between Manchu noblemen and Han officials who had passed the highest levels of the state examinations. The Grand Secretariat,[d] which had been an important policy-making body under the Ming, lost its importance during the Qing and evolved into an imperial chancery. The institutions which had been inherited from the Ming formed the core of the Qing "", which handled routine matters and was located in the southern part of the Forbidden City.

In order not to let the routine administration take over the running of the empire, the Qing emperors made sure that all important matters were decided in the "", which was dominated by the imperial family and Manchu nobility and which was located in the northern part of the Forbidden City. The core institution of the inner court was the Grand Council.[e] It emerged in the 1720s under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor as a body charged with handling Qing military campaigns against the Mongols, but soon took over other military and administrative duties, centralizing authority under the crown.[3] The Grand Councillors[f] served as a sort of privy council to the emperor.

The Six Ministries and their respective areas of responsibilities were as follows:

Board of Civil Appointments[g]

- The personnel administration of all civil officials – including evaluation, promotion, and dismissal. It was also in charge of the "honours list".

- The literal translation of the Chinese word hu (戶; 户) is "household". For much of Qing history, the government's main source of revenue came from taxation on landownership supplemented by official monopolies on salt, which was an essential household item, and tea. Thus, in the predominantly agrarian Qing dynasty, the "household" was the basis of imperial finance. The department was charged with revenue collection and the financial management of the government.

- This board was responsible for all matters concerning court protocol. It organized the periodic worship of ancestors and various gods by the emperor, managed relations with tributary nations, and oversaw the nationwide civil examination system.

- Unlike its Ming predecessor, which had full control over all military matters, the Qing Board of War had very limited powers. First, the Eight Banners were under the direct control of the emperor and hereditary Manchu and Mongol princes, leaving only the Green Standard Army under ministerial control. Furthermore, the ministry's functions were purely administrative. Campaigns and troop movements were monitored and directed by the emperor, first through the Manchu ruling council, and later through the Grand Council.

- The Board of Punishments handled all legal matters, including the supervision of various law courts and prisons. The Qing legal framework was relatively weak compared to modern-day legal systems, as there was no separation of executive and legislative branches of government. The legal system could be inconsistent, and, at times, arbitrary, because the emperor ruled by decree and had final say on all judicial outcomes. Emperors could (and did) overturn judgements of lower courts from time to time. Fairness of treatment was also an issue under the system of control practised by the Manchu government over the Han Chinese majority. To counter these inadequacies and keep the population in line, the Qing government maintained a very harsh penal code towards the Han populace, but it was no more severe than previous Chinese dynasties.[citation needed]

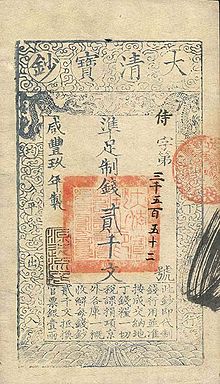

- The Board of Works handled all governmental building projects, including palaces, temples and the repairs of waterways and flood canals. It was also in charge of minting coinage.

From the early Qing, the central government was characterized by a system of dual appointments by which each position in the central government had a Manchu and a Han Chinese assigned to it. The Han Chinese appointee was required to do the substantive work and the Manchu to ensure Han loyalty to Qing rule.[4]

In addition to the six boards, there was a Lifan Yuan[m] unique to the Qing government. This institution was established to supervise the administration of Tibet and the Mongol lands. As the empire expanded, it took over administrative responsibility of all minority ethnic groups living in and around the empire, including early contacts with Russia – then seen as a tribute nation. The office had the status of a full ministry and was headed by officials of equal rank. However, appointees were at first restricted only to candidates of Manchu and Mongol ethnicity, until later open to Han Chinese as well.[citation needed]

Even though the Board of Rites and Lifan Yuan performed some duties of a foreign office, they fell short of developing into a professional foreign service. It was not until 1861 – a year after losing the Second Opium War to the Anglo-French coalition – that the Qing government bowed to foreign pressure and created a proper foreign affairs office known as the Zongli Yamen. The office was originally intended to be temporary and was staffed by officials seconded from the Grand Council. However, as dealings with foreigners became increasingly complicated and frequent, the office grew in size and importance, aided by revenue from customs duties which came under its direct jurisdiction.

There was also another government institution called Imperial Household Department which was unique to the Qing dynasty. It was established before the fall of the Ming, but it became mature only after 1661, following the death of the Shunzhi Emperor and the accession of his son, the Kangxi Emperor.[5] The department's original purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the imperial family and the activities of the inner palace (in which tasks it largely replaced eunuchs), but it also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, engaged in trading activities (jade, ginseng, salt, furs, etc.), managed textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books.[6] Relations with the Salt Superintendents and salt merchants, such as those at Yangzhou, were particularly lucrative, especially since they were direct, and did not go through absorptive layers of bureaucracy. The department was manned by booi,[n] or "bondservants," from the Upper Three Banners.[7] By the 19th century, it managed the activities of at least 56 subagencies.[5][8]

Administrative divisions[]

Qing China reached its largest extent during the 18th century, when it ruled China proper (eighteen provinces) as well as the areas of present-day Northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet, at approximately 13 million km2 in size. There were originally 18 provinces, all of which in China proper, but later this number was increased to 22, with Manchuria and Xinjiang being divided or turned into provinces. Taiwan, originally part of Fujian province, became a province of its own in the 19th century, but was ceded to the Empire of Japan following the First Sino-Japanese War by the end of the century. In addition, many surrounding countries, such as Korea (Joseon dynasty), Vietnam frequently paid tribute to China during much of this period. The Katoor dynasty of Afghanistan also paid tribute to the Qing dynasty of China until the mid-19th century.[9][full citation needed] During the Qing dynasty the Chinese claimed suzerainty over the Taghdumbash Pamir in the south-west of Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County but permitted the Mir of Hunza to administer the region in return for a tribute. Until 1937 the inhabitants paid tribute to the Mir of Hunza, who exercised control over the pastures.[10] Khanate of Kokand were forced to submit as protectorate and pay tribute to the Qing dynasty in China between 1774 and 1798.

- Northern and southern circuits of Tian Shan (later became Xinjiang province) – sometimes the small semi-autonomous Kumul Khanate and Turfan Khanate are placed into an "Eastern Circuit"

- Outer Mongolia – Khalkha, Kobdo league, Köbsgöl, Tannu Urianha

- Inner Mongolia – 6 leagues (Jirim, Josotu, Juu Uda, Shilingol, Ulaan Chab, Ihe Juu)

- Other Mongolian leagues – Alshaa khoshuu (League-level khoshuu), Ejine khoshuu, Ili khoshuu (in Xinjiang), Köke Nuur league; directly ruled areas: Dariganga (Special region designated as Emperor's pasture), Guihua Tümed, Chakhar, Hulunbuir

- Tibet (Ü-Tsang and western Kham, approximately the area of present-day Tibet Autonomous Region)

- Manchuria (Northeast China, later became provinces)

- Eighteen provinces (China proper provinces)

- Additional provinces in the late Qing dynasty

- Gansu-Xinjiang

- Fujian-Taiwan (until 1895)

- Fengtian

- Jilin

- Heilongjiang

Territorial administration[]

The Qing organization of provinces was based on the fifteen administrative units set up by the Ming dynasty, later made into eighteen provinces by splitting for example, Huguang into Hubei and Hunan provinces. The provincial bureaucracy continued the Yuan and Ming practice of three parallel lines, civil, military, and censorate, or surveillance. Each province was administered by a governor (巡撫, xunfu) and a provincial military commander (提督, tidu). Below the province were prefectures (府, fu) operating under a prefect (知府, zhīfǔ), followed by subprefectures under a subprefect. The lowest unit was the county, overseen by a county magistrate. The eighteen provinces are also known as "China proper". The position of viceroy or governor-general (總督, zongdu) was the highest rank in the provincial administration. There were eight regional viceroys in China proper, each usually took charge of two or three provinces. The Viceroy of Zhili, who was responsible for the area surrounding the capital Beijing, is usually considered as the most honorable and powerful viceroy among the eight.

- Viceroy of Zhili – in charge of Zhili

- Viceroy of Shaan-Gan – in charge of Shaanxi and Gansu

- Viceroy of Liangjiang – in charge of Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Anhui

- Viceroy of Huguang – in charge of Hubei and Hunan

- Viceroy of Sichuan – in charge of Sichuan

- Viceroy of Min-Zhe – in charge of Fujian, Taiwan, and Zhejiang

- Viceroy of Liangguang – in charge of Guangdong and Guangxi

- Viceroy of Yun-Gui – in charge of Yunnan and Guizhou

By the mid-18th century, the Qing had successfully put outer regions such as Inner and Outer Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang under its control. Imperial commissioners and garrisons were sent to Mongolia and Tibet to oversee their affairs. These territories were also under supervision of a central government institution called Lifan Yuan. Qinghai was also put under direct control of the Qing court. Xinjiang, also known as Chinese Turkestan, was subdivided into the regions north and south of the Tian Shan mountains, also known today as Dzungaria and Tarim Basin respectively, but the post of Ili General was established in 1762 to exercise unified military and administrative jurisdiction over both regions. Dzungaria was fully opened to Han migration by the Qianlong Emperor from the beginning. Han migrants were at first forbidden from permanently settling in the Tarim Basin but were the ban was lifted after the invasion by Jahangir Khoja in the 1820s. Likewise, Manchuria was also governed by military generals until its division into provinces, though some areas of Xinjiang and Northeast China were lost to the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. Manchuria was originally separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, a ditch and embankment planted with willows intended to restrict the movement of the Han Chinese, as the area was off-limits to civilian Han Chinese until the government started colonizing the area, especially since the 1860s.[11]

With respect to these outer regions, the Qing maintained imperial control, with the emperor acting as Mongol khan, patron of Tibetan Buddhism and protector of Muslims. However, Qing policy changed with the establishment of Xinjiang province in 1884. During The Great Game era, taking advantage of the Dungan revolt in northwest China, Yaqub Beg invaded Xinjiang from Central Asia with support from the British Empire, and made himself the ruler of the kingdom of Kashgaria. The Qing court sent forces to defeat Yaqub Beg and Xinjiang was reconquered, and then the political system of China proper was formally applied onto Xinjiang. The Kumul Khanate, which was incorporated into the Qing empire as a vassal after helping Qing defeat the Zunghars in 1757, maintained its status after Xinjiang turned into a province through the end of the dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution up until 1930.[12] In the early 20th century, Britain sent an expedition force to Tibet and forced Tibetans to sign a treaty. The Qing court responded by asserting Chinese sovereignty over Tibet,[13] resulting in the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Convention signed between Britain and China. The British agreed not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet, while China engaged not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.[14] Furthermore, similar to Xinjiang which was converted into a province earlier, the Qing government also turned Manchuria into three provinces in the early 20th century, officially known as the "Three Northeast Provinces", and established the post of Viceroy of the Three Northeast Provinces to oversee these provinces, making the total number of regional viceroys to nine.

| hideTerritorial Administration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes[]

- ^ Chinese: 六部; pinyin: lìubù

- ^ traditional Chinese: 尚書; simplified Chinese: 尚书; pinyin: shàngshū; Manchu: ᠠᠯᡳᡥᠠ

ᠠᠮᠪᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: aliha amban; Abkai: aliha amban - ^ Chinese: 侍郎; pinyin: shìláng; Manchu: ᠠᠰᡥᠠᠨ ᡳ

ᠠᠮᠪᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: ashan i amban; Abkai: ashan-i amban - ^ traditional Chinese: 內閣; simplified Chinese: 内阁; pinyin: nèigé; Manchu: ᡩᠣᡵᡤᡳ

ᠶᠠᠮᡠᠨ; Möllendorff: dorgi yamun; Abkai: dorgi yamun - ^ traditional Chinese: 軍機處; simplified Chinese: 军机处; pinyin: jūnjī chù; Manchu: ᠴᠣᡠ᠋ᡥᠠᡳ

ᠨᠠᠰᡥᡡᠨ ᡳ

ᠪᠠ; Möllendorff: coohai nashūn i ba; Abkai: qouhai nashvn-i ba - ^ traditional Chinese: 軍機大臣; simplified Chinese: 军机大臣; pinyin: jūnjī dàchén

- ^ Chinese: 吏部; pinyin: lìbù; Manchu: ᡥᠠᡶᠠᠨ ᡳ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: hafan i jurgan; Abkai: hafan-i jurgan - ^ 戶部; 户部; hùbù; Manchu: ᠪᠣᡳ᠌ᡤᠣᠨ ᡳ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: boigon i jurgan; Abkai: boigon-i jurgan - ^ simplified Chinese: 礼部; traditional Chinese: 禮部; pinyin: lǐbù; Manchu: ᡩᠣᡵᠣᠯᠣᠨ ᡳ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: dorolon i jurgan; Abkai: dorolon-i jurgan - ^ Chinese: 兵部; pinyin: bīngbù; Manchu: ᠴᠣᡠ᠋ᡥᠠᡳ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: coohai jurgan; Abkai: qouhai jurgan - ^ Chinese: 刑部; pinyin: xíngbù; Manchu: ᠪᡝᡳ᠌ᡩᡝᡵᡝ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: beidere jurgan; Abkai: beidere jurgan - ^ Chinese: 工部; pinyin: gōngbù; Manchu: ᠸᡝᡳ᠌ᠯᡝᡵᡝ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: weilere jurgan; Abkai: weilere jurgan - ^ Chinese: 理藩院; pinyin: Lǐfànyuàn; Manchu: ᡨᡠᠯᡝᡵᡤᡳ

ᡤᠣᠯᠣ ᠪᡝ

ᡩᠠᠰᠠᡵᠠ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ; Möllendorff: Tulergi golo be dasara jurgan; Abkai: Tulergi golo be dasara jurgan - ^ Chinese: 包衣; pinyin: bāoyī; Manchu: ᠪᠣᡠ᠋ᡳ; Möllendorff: booi; Abkai: boui

References[]

- ^ Spence (2012), p. 39.

- ^ Jackson & Hugus (1999), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Bartlett (1991).

- ^ "The Rise of the Manchus". University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rawski (1998), p. 179.

- ^ Rawski (1998), pp. 179–180.

- ^ Torbert (1977), p. 27.

- ^ Torbert (1977), p. 28.

- ^ sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/26/2602579.pdf

- ^ "Yak keeping in Western High Asia: Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Southern Xinjiang Pakistan, by Hermann Kreutzmann[12]". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Elliott (2000), p. [page needed].

- ^ Millward (2007), p. 190.

- ^ "<untitled>" (PDF). The New York Times. 19 January 1906.

- ^ . 1906 – via Wikisource.

- Qing dynasty