Jazira Region

Jazira Region

| |

|---|---|

One of seven de facto regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria | |

Seal | |

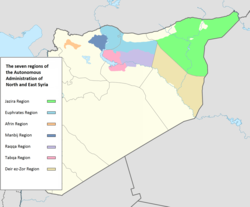

The regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the Jazira Region in green. | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Al Hasakah |

| De facto Administration | |

| Autonomy declared | January 21, 2014 |

| Administrative center | Qamishli[1] |

| Government | |

| • Prime Minister | Akram Hesso |

| • Co-Vice President | Elizabeth Gawrie |

| • Co-Vice President | Hussein Taza Al Azam |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2011[2]) | 1,512,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | +963 52 |

| Official languages | Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac |

The Jazira Region, formerly Jazira Canton, (Kurdish: Herêma Cizîrê, Arabic: إقليم الجزيرة, Syriac: ܦܢܝܬܐ ܕܓܙܪܬܐ, romanized: Ponyotho d'Gozarto), is the largest of the three original regions of the de facto Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). As part of the ongoing Rojava conflict, its democratic autonomy was officially declared on 21 January 2014.[3] The region is in the Al-Hasakah Governorate (formerly known as the Al-Jazira Province) of Syria.

According to the AANES constitution, the city of Qamishli is the administrative center of Jazira Region.[4] However, as parts of Qamishli remain under the control of Syrian government forces, meetings of the autonomous region's administration take place in the nearby city of Amuda.[3]

The region has two subordinate cantons, the consisting of the al-Hasakah area (with the Al-Shaddadi, and Al-Hawl districts subordinate to it), the Al-Darbasiyah area, and the Tell Tamer area, as well as the Qamishli canton consisting of the Qamishli area (with the , , and districts subordinate to it) and the Derîk area (with the Girkê Legê, and Çilaxa districts subordinate to it).[5]

Demographics[]

Jazira Region's ethnic groups include Kurds, Arabs, Arameans (Syriacs, Assyrians and Chaldeans), Armenians and Yazidis. While Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac are official languages, all communities have the right to teach and be taught in their native language. Religions practiced in the region are Islam, Christianity and Yazidism.[4] The majority of the Arabs and Kurds in the region are Sunni Muslim. Between 20-30% of the people of Al-Hasakeh city are Christians of various churches and denominations.[6]

Cities and towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants according to the 2004 Syrian census are Hasakah (188,160), Qamishli (184,231), Amuda (26,821), Al-Malikiyah (26,311), Al-Qahtaniyah (16,946), Al-Shaddadah (15,806), Al-Muabbada (15,759), Al-Sabaa wa Arbain (14,177) and Al-Manajir (12,156).

The Jazira region has been home to one of the largest concentrations of Christians in Syria. Many of the cities where founded by Christian communities. In 1927 the regions population was recorded as the following table.[7]

| Cities | Total Population | Christian Population |

|---|---|---|

| Ras al-Ayn | 3,000 | 2,000 |

| Al-Darbasiyah | 1,500 | 1,000 |

| Amuda | 2,800 | 2,000 |

| Qamishli | 12,000 | 8,000 |

| Al-Malikiyah (Dayrik) | 1,900 | 900 |

| Al-Qahtaniyah | 3,000 | 2,000 |

| Ain Diwar | 1,000 | 600 |

| Al-Hasakah | 9,000 | 8,500 |

| Tell Brak | 500 | 500 |

| Total | 34,700 | 25,500 |

History[]

In the late 10th century , the Kurdish Humaydi tribe had their winter pastures in the Jazira region and clashed with forces of Buyid ruler Adud al-Dawla.[8] During the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia. The largest of these tribal groups was the Reshwan confederation, which was initially based in Adıyaman Province but eventually also settled throughout Anatolia. The Milli confederation, mentioned in 1518 onward, was the most powerful group and dominated the entire northern Syrian steppe in the second half of the 18th century. Danish writer C. Niebuhr who traveled to Jazira in 1764 recorded five nomadic Kurdish tribes (Dukurie, Kikie, Schechchanie, Mullie and Aschetie) and six Arab tribes (Tay, Kaab, Baggara, Geheish, Diabat and Sherabeh).[9] According to Niebuhr, the Kurdish tribes were settled near Mardin in Turkey, and paid the governor of that city for the right to graze their herds in the Syrian Jazira.[10][11] The Kurdish tribes gradually settled in villages and cities and are still present in Jazira (modern Syria's Hasakah Governorate).[12] The Ottoman province of Diyarbekir, which included parts of modern-day northern Syria, was called Eyalet-i Kurdistan during the Tanzimat reforms period (1839–67).[13] Until the 19th century, Kurdistan did not include the lands of Syrian Jazira in some books.[note 1][14] The Treaty of Sèvres' putative Kurdistan did not include any part of today's Syria.[15] According to McDowall, Kurds slightly outnumbered Arabs in Jazira in 1918.[16]

The demographics of Northern Syria saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century when the Ottoman Empire (Turks) conducted ethnic cleansing of its Armenian and Aramean(Syriac, Assyrian and Chaldean) Christian populations and some Kurdish tribes joined in the atrocities committed against them.[17][18][19] Many Arameans fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[20][21][22]

Until the 19th century, Kurdistan did not include the lands of Syrian Jazira in some books.[note 2][14] According to McDowall, Kurds slightly outnumbered Arabs in Jazira in 1918.[16]

Starting in 1926, the region saw huge immigration of Kurds following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[23] While many of the Kurds in Syria have been there for centuries, waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syria, where they were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities.[24] This large influx of Kurds moved to Syria’s Jazira province. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.[25]

In the late 1930s a small but vigorous separatist movement emerged in Qamishli. With some support from French Mandate officials, the movement actively lobbied for autonomy direct under French rule and separation from Syria on the ground that majority of the inhabitants were not Arabs. Syrian nationalists saw the movement as a profound threat to their eventual rule. The Syrian nationalists allied with local Arab Shammal tribal leader and Kurdish tribes. They together attacked the Christian movement in many towns and villages. Local Kurdish tribes who were allies of Shammar tribe sacked and burned Aramean town of Amuda.[26][27][28] In 1941, the Aramean community of al-Malikiyah was subjected to a vicious assault. Even though the assault failed, Arameans felt threatened and left in large numbers, and the immigration of Kurds from Turkey to the area converted al-Malikiya, al-Darbasiyah and Amuda to Kurdish-majority cities.

According to the French report to the League of Nations in 1937, the population of Jazira consisted of 82,000 Kurdish villagers, 42,000 Muslim Arab pastoralists, and 32,000 Christian town dwellers (Arameans and Armenians).[29]

Between 1932 and 1939, a Kurdish-Christian autonomy movement emerged in Jazira. The demands of the movement were autonomous status similar to the Sanjak of Alexandretta, the protection of French troops, promotion of Kurdish language in schools and hiring of Kurdish officials. The movement was led by Michel Dome, mayor of Qamishli, Hanna Hebe, general vicar for the Syriac-Catholic Patriarch of Jazira, and the Kurdish notable Hajo Agha. Some Arab tribes supported the autonomists while others sided with the central government. In the legislative elections of 1936, autonomist candidates won all the parliamentary seats in Jazira and Jarabulus, while the nationalist Arab movement known as the National Bloc won the elections in the rest of Syria. After victory, the National Bloc pursued an aggressive policy toward the autonomists. The Jazira governor appointed by Damascus intended to disarm the population and encourage the settlement of Arab farmers from Aleppo, Homs and Hama in Jazira.[30] In July 1937, armed conflict broke out between the Syrian police and the supporters of the movement. As a result, the governor and a significant portion of the police force fled the region and the rebels established local autonomous administration in Jazira.[31] In August 1937 a number of Arameans/Syriacs in Amuda were killed by a pro-Damascus Kurdish chief.[32] In September 1938, Hajo Agha chaired a general conference in Jazira and appealed to France for self-government.[33] The new French High Commissioner, Gabriel Puaux, dissolved parliament and created autonomous administrations for Jabal Druze, Latakia and Jazira in 1939 which lasted until 1943.[34]

Politics and administration[]

Legislative Assembly[]

All four main ethnic communities (Kurds, Arabs, Armenians and Arameans (Assyrians/Syriacs) are represented in the 101-seat Legislative Assembly.[35] The current prime minister (sometimes referred to as president) of Jazira Canton is the Kurdish with Arab Hussein Taza Al Azam and Aramean/Syriac Elizabeth Gawrie as deputy prime ministers (sometimes referred to as vice-presidents).[36]

There are people's councils but it is unclear how they relate to the transitional government.

There also appear to be co-governor/co-president positions, with tribal leader and Al-Sanadid Forces leader Humaydi Daham al-Hadi and Hediye Yusuf being co-governors of the region.[37][38][39][40][41]

Notable legislation[]

In January 2016, Jazira Canton introduced a "self-defense duty" conscription law for its self-defence forces, including an avoidance fee for residents of age for mandatory military service who have moved to Europe, to pay $200 for each year of absence upon their return.[42]

In September 2015, the legislative council passed the Law for the Management and Protection of the Assets of the Refugees and the Absentees, under which a real estate owner loses title when he does not make personal use of the property. In particular among the Arameans community in Jazira Region, persistent opposition was voiced, as their community is disproportionally hit by the measure, for both a high degree of real estate ownership and a particularly high share of outbound civil war refugees.[43] Aramean/Syriac organizations of the region published several statements making accusations of seizing private property, demographic changing and ethnic cleansing.[44][43] Assets seized from Arameans/Syriacs under the law have reportedly since been handed over to Syriac churches.[43]

Police[]

Security is maintained by the Asayish police force and its Aramean/Syriac counterpart, the Sootoro. Syrian government loyalists only control a number of demarcated neighborhoods in Qamishli.[45] The government-held areas in Qamishli include the city's airport, the city's train station, the border crossing, the governor's palace, and many other residential neighborhoods with various governmental buildings such as hospitals and fire departments.

List of executive officers[]

| Name | Party | Office | Elected | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PYD | Prime Minister | 2014 | |||

| SUP | Deputy Prime Minister | 2014 | |||

| PB-ASD | Deputy Prime Minister | 2014 | |||

| Abulkarim Omer | N/A | Foreign Minister | 2015 | Replaced Salih Gedo | |

| Abdulkarim Sarokhan | N/A | Minister of Defense | 2014 | ||

| Kanaan Barakat | N/A | Interior Minister | 2014 | ||

| Abdulmenar Yoxo | SUP | Minister of Regional Commissions, Councils and Planning |

2014 | ||

| Emziye Muhammed | PB-ASD | Minister of Finance | 2014 | ||

| Dijwar Ehmed Axa | N/A | Minister of Labor and Social Security |

2014 | ||

| Mihemed Salih Abo | N/A | Minister of Education | 2014 | ||

| Abdulmecid Sebri | N/A | Minister of Agriculture Minister of Health |

2014 | ||

| Siham Kiryo | SUP | Minister of Trade and Economy | 2014 | ||

| Rezan Gulo | N/A | Minister of Martyrs’ Families | 2014 | ||

| Mehawan Mihemed Hesen | N/A | Minister of Culture | 2014 | ||

| Mihemed Hesen Ubeyd | N/A | Minister of Transportation | 2014 | ||

| Mihemed İsa Fatimi | N/A | Minister of Youth and Sport | 2014 | ||

| Lokman Ehme | N/A | Minister of the Environment and Tourism |

2014 | ||

| Şex Mihemed Qadiri | N/A | Minister of Religious Affairs | 2014 | ||

| Emine Umer | N/A | Minister of Women and Family Affairs |

2014 | ||

| Senherid Basom | SUP | Minister of Human Rights | 2014 | ||

| Temer Hesen Cahid | N/A | Minister of Industry and Commerce |

2014 | ||

| Salal Mihemed | N/A | Minister of Information and Communication |

2014 | ||

| Abdulhamit Bekir | N/A | Minister of Justice | 2014 | ||

| Süleyman Xelek | N/A | Minister of Electricity, Industry and Natural Resources |

2014 | ||

Economy[]

The economy of Jazira Canzon mainly based on agriculture, it accounts for 17 percent of Syria's agricultural production, in particular wheat and cotton grown there in abundance.[46] Being the "bread basket" of Syria, wheat production before the Syrian Civil War used to be around 1,8 million tons per year, at the height of the war however dropping as low as 0,5 million tons.[46] The Economy Committee promotes varied vegetable and fruit cultivation instead of the mono-culture of wheat; in Amuda a centre to develop seedlings has been created.[47] Development of a greenhouse economy is promoted.[48] In Al-Qahtaniyah, an ecological village was founded so that local Rojavan population can acquire experience in ecology from international volunteers.[47] By 2020, there have been established 40 workers cooperatives with between five to ten families each. Eighteen are organized by Aborija Jin of the Kongra Star, an organization focused on the female activities in the AANES.[49]

The only significant industrial area is in Hasakah.[47]

Jazira Region is home to several oil fields, among them Syria's best producing one at Rmelan. As of summer 2016, oil output in Jazira Region was estimated at around 40,000 barrels per day.[43] Some people work at primitive oil refining, which causes health hazards and pollution.[50] The oil wealth in combination with the economic blockade of the AANES from the adjacent territories controlled by Turkey, and partially also the KRG, results in a distortion of relative prices; petrol costs only half as much as bottled water.[47]

Electricity is supplied by Tishrin Dam on the Euphrates, within Euphrates Region; apart from that, electricity is produced by diesel generators.[47]

Taxation[]

In July 2017, Jazira Region became the first region in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria to introduce an income tax, with citizens' income of above 100,000 Syrian pound (at the time equivalent to around 200 U.S. dollar) per month to be taxed.[51]

Education[]

Like in the other Rojava regions, primary education in the public schools is initially by mother tongue instruction either Kurdish or Arabic, with the aim of bilingualism in Kurdish and Arabic in secondary schooling.[52][53] Curricula are a topic of continuous debate between the regions' Boards of Education and the Syrian central government in Damascus, which partly pays the teachers.[54][55][56][57] In August 2016, the Ourhi Centre in the city of Qamishli was founded by the Syriac community, to educate teachers in order to make the Syriac-Aramaic an additional language to be taught in public schools in Jazira Region,[58][59] which then started with the 2016/17 academic year.[54] With that academic year, states the Rojava Education Committee, "three curriculums have replaced the old one, to include teaching in three languages: Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac (Aramaic)"[60]

The federal, regional and local administrations in Rojava put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities. One cited example is the 2015 established Nahawand Center for Developing Children’s Talents in Amuda.[61]

The Jazira Region Board of Education operates two public institutions of higher education, the University of Rojava and the Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy, both in the city of Qamishli. Jazira Region houses a third one, the Hasakah campus of Al-Furat University, which is operated by the Damascus government Ministry of Higher Education.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Modern Curdistan is of much greater extent than the ancient Assyria, and is composed of two parts, the Upper and Lower. In the former is the province of Ardelaw, the ancient Arropachatis, now nominally a part of Irak Ajami, and belonging to the north-west division called Al Jobal. It contains five others, namely, Betlis, the ancient Carduchia, lying to the south and south-west of the lake Van. East and south-east of Betlis is the principality of Julamerick—south-west of it, is the principality of Amadia—the fourth is Jeezera ul Omar, a city on an island in the Tigris, and corresponding to the ancient city of Bezabde—the fifth and largest is Kara Djiolan, with a capital of the same name. The pashalics of Kirkook and Solimania also comprise part of Upper Curdistan. Lower Curdistan comprises all the level tract to the east of the Tigris, and the minor ranges immediately bounding the plains, and reaching thence to the foot of the great range, which may justly be denominated the Alps of western Asia.

A Dictionary of Scripture Geography (1846), John Miles.[14] - ^ Modern Curdistan is of much greater extent than the ancient Assyria, and is composed of two parts, the Upper and Lower. In the former is the province of Ardelaw, the ancient Arropachatis, now nominally a part of Irak Ajami, and belonging to the north-west division called Al Jobal. It contains five others, namely, Betlis, the ancient Carduchia, lying to the south and south-west of the lake Van. East and south-east of Betlis is the principality of Julamerick—south-west of it, is the principality of Amadia—the fourth is Jeezera ul Omar, a city on an island in the Tigris, and corresponding to the ancient city of Bezabde—the fifth and largest is Kara Djiolan, with a capital of the same name. The pashalics of Kirkook and Solimania also comprise part of Upper Curdistan. Lower Curdistan comprises all the level tract to the east of the Tigris, and the minor ranges immediately bounding the plains, and reaching thence to the foot of the great range, which may justly be denominated the Alps of western Asia.

A Dictionary of Scripture Geography (1846), John Miles.[14]

References[]

- ^ Abboud 2018, Table 4.1 Cantons of the Rojava Administration.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Al-Qamishli to be capital city of Jazeera Canton in Syrian Kurdistan". Firat News. 26 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons". Personal Website of Mutlu Civiroglu.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2017-11-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Al-Hasakeh Governorate profile" (PDF). www.acaps.org.

- ^ Mundy, Martha (2000). The Transformation of Nomadic Society in the Arab East. University Of Cambridge Oriental Publications: Harvard. p. 72.

- ^ Asa Eger, A. (2015). The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities. I.B.Tauris. p. 269. ISBN 9781780761572.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 419.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 0415072654.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 389.

- ^ Stefan Sperl, Philip G. Kreyenbroek (1992). The Kurds a Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-203-99341-1.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. BRILL. p. 6. ISBN 9789004225183.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d John R. Miles (1846). A Dictionary of Scripture Geography. Fourth edition. J. Johnson & Son, Manchester. p. 57.

- ^ David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 137. ISBN 9781850434160.

- ^ Jump up to: a b David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 469. ISBN 9781850434160.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2007). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. ISBN 9781412835923. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown (2004). On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. p. 199. ISBN 9780953824861.

- ^ Lazar, David William, not dated A brief history of the plight of the Christian Assyrians* in modern-day Iraq Archived 2015-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. American Mespopotamian.

- ^ R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 24. ISBN 9781593334130.

- ^ "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162. ISBN 9780838639429.

- ^ Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- ^ Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- ^ McDowell, David (2005). A modern history of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1850434166.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 159. ISBN 9780838639429.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. p. 147. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ Keith David Watenpaugh (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. p. 270. ISBN 9781400866663.

- ^ McDowell, David (2004). A modern history of the Kurds. Tauris. p. 470.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. pp. 29, 30, 35. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ Romano, David; Gurses, Mehmet (2014). Conflict,Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 146.

- ^ McDowell, David (2004). A modern history of the Kurds. Tauris. p. 471.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ "Declaration of democratic autonomy in Cizîre canton". Archived from the original on 2014-12-23.

- ^ Karlos Zurutuza (28 October 2014). "Democracy is "Radical" in Northern Syria". Inter Press Service.

- ^ "YPG, backed by al-Khabour Guards Forces, al-Sanadid army and the Syriac Military Council, expels IS out of more than 230 towns, villages and farmlands". Syrian Observatory For Human Rights. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Gupta, Rahila (9 April 2016). "Rojava's commitment to Jineolojî: the science of women". openDemocracy. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "SDF plays central role in Syrian civil war" (PDF). IHS Jane's 360. IHS. 20 January 2016. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Sanadid fighters promote their participation in Wrath of Euphrates". Hawar News Agency. 9 January 2017. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben (2 November 2015). "New U.S.-backed alliance to counter ISIS in Syria falters". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ "canton imposes new 'luxury' tax on residents living in Europe". Syria Direct.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "NO GOING BACK: WHY DECENTRALISATION IS THE FUTURE FOR SYRIA" (PDF). European Council on Foreign Relations. September 2016.

- ^ "Assyrian leader accuses PYD of monopolizing power in Syria's north". ARA. 23 March 2016.

- ^ Carl Drott (6 March 2014). "A Christian militia splits in Al-Qamishli". Carnegie Endowment.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Rojava: The Economic Branches in Detail". cooperativeeconomy.info. 14 January 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "The Greenhouse Project". cooperativeeconomy.info. 24 April 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Explainer: Cooperatives in North and East Syria – developing a new economy". www.resilience.org. Rojava Information Center. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Control of Syrian Oil Fuels War Between Kurds and Islamic State". The Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2014.

- ^ "Rojava Administration to impose tax system in northern Syria". ARA News. 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Education in Rojava after the revolution". ANF. 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Hassakeh: Syriac Language to Be Taught in PYD-controlled Schools". The Syrian Observer. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ "Kurds introduce own curriculum at schools of Rojava". Ara News. 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Education in Rojava: Academy and Pluralistic versus University and Monisma". Kurdishquestion. 2014-01-12. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Syriac Christians revive ancient language despite war". ARA News. 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ "The Syriacs are taught their language for the first time". Hawar News Agency. 2016-09-24. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ "Rojava administration launches new curriculum in Kurdish, Arabic and Assyrian". ARA News. 7 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ^ "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

Works cited[]

- Abboud, Samer N. (2018). Syria: Hot Spots in Global Politics. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1-509-52241-5.

External links[]

- Map of majority ethnicities in Syria by Gulf2000 project of Columbia university

- States and territories established in 2014

- 2014 establishments in Syria

- Al-Hasakah Governorate

- Al-Hasakah Governorate in the Syrian civil war

- Jazira Region