Yazidism

This article or section should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}} or {{transl}} (or {{IPA}} or similar for phonetic transcriptions), with an appropriate ISO 639 code. (August 2021) |

| Yazidism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Monotheistic |

| Mir | Hazim Tahsin or Naif Dawud[1] |

| Baba Sheikh | Sheikh Ali Ilyas[2] |

| Headquarters | Ain Sifni |

| Other name(s) | Şerfedîn |

Yazidism or Sharfadin[3] (Kurdish: شهرفهدین, Êzdiyatî, Êzdîtî, Şerfedîn,)[4][5][6] is a monotheistic ethnic religion that has roots in a western Iranic pre-Zoroastrian religion directly derived from the Indo-Iranian tradition, although other, less common and more outdated narratives link the religion to Zoroastrianism and even Ancient Mesopotamian religions.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] Yezidism is followed by the mainly Kurmanji-speaking Yazidis and is based on belief in one God who created the world and entrusted it into the care of seven Holy Beings, known as Angels.[3][14][15] Preeminent among these Angels is Tawûsê Melek (also spelled as "Melek Taûs"), who is the leader of the Angels and who has authority over the world.[3][15][16][17]

Principal beliefs[]

Yezidis believe in one God, whom they refer to as Xwedê, Xwedawend, Êzdan, and, less commonly, Heq.[6][14][3][18] According to some Yazidi hymns (known as Qewls), God has 1001 names.[19] In Yezidism, fire, water, air, and the earth are sacred elements that are not to be polluted. During prayer Yezidis face towards the sun, for which they were often called ‘sun worshippers’. The Yezidi myth of creation begins with the description of the emptiness and the absence of order in the Universe. Prior to the World's creation, God created a white pearl (Kurdish: dur) in the spiritual form from his own pure Light and alone dwelt in it.[20] First there was an esoteric world, and after that an exoteric world was created. Before the creation of this world God created seven Divine Beings (often called "Angels" in Yazidi literature) to whom he assigned all the world's affairs; the leader of the Seven Angels was appointed Tawûsî Melek ("Peacock Angel").[3][15][16] The end of Creation is closely connected with the creation of mankind and the transition from mythological to historical time.[6][17][14]

Tawûsê Melek[]

The Yazidis believe in a divine Triad.[3][15][16] The original, hidden God of the Yazidis is considered to be remote and inactive in relation to his creation, except to contain and bind it together within his essence.[3][21] His first emanation is Melek Taûs (Tawûsê Melek), who functions as the ruler of the world.[3][15][16] The second hypostasis of the divine Triad is the Sheikh 'Adī ibn Musafir. The third is Sultan Ezid. These are the three hypostases of the one God. The identity of these three is sometimes blurred, with Sheikh 'Adī considered to be a manifestation of Tawûsê Melek and vice versa; the same also applies to Sultan Ezid. A popular Yazidi story narrates the fall of Tawûsê Melek and his subsequent rejection by humanity, with the exception of the Yazidis.[3] Yazidis are called Miletê Tawûsê Melek ("the nation of Tawûsê Melek").[22]

In the Yazidi myth of creation, Tawûsê Melek refused to bow before Adam, the first human, when God ordered the Seven Angels to do so.[3][15][16] The command was actually a test, meant to determine which of these angels was most loyal to God by not prostrating themselves to someone other than their creator.[3][15][16][23] This belief has been linked by some people to the Islamic mythological narrative on Iblis, who also refused to prostrate to Adam, despite God's express command to do so.[3][15][16] Because of this similarity to the Islamic tradition of Iblis, Muslims and followers of other Abrahamic religions have erroneously associated and identified the Peacock Angel with their own conception of the unredeemed evil spirit Satan,[3][15][16][24]:29[25] a misconception which has incited centuries of violent religious persecution of the Yazidis as "devil-worshippers".[3][15][16][26][27] Persecution of Yazidis has continued in their home communities within the borders of modern Iraq.[3][15][28]

Yazidis, however, believe Tawûsê Melek is not a source of evil or wickedness.[3][15][16] They consider him to be the leader of the archangels, not a fallen angel.[3][16][24][25] Yazidis argue that the order to bow to Adam was only a test for Tawûsê Melek, since if God commands anything then it must happen. In other words, God could have made him submit to Adam, but gave Tawûsê Melek the choice as a test: God had directed him not to bow to any other being, and his refusal of the later order to bow to Adam was thus obedience to God's original command.[3][15][16][23]

The Yazidis of Kurdistan have been called many things, most notoriously 'devil-worshippers', a term used both by unsympathetic neighbours and fascinated Westerners. This sensational epithet is not only deeply offensive to the Yazidis themselves, but quite simply wrong.[29] Non-Yazidis have associated Melek Taus with Shaitan (Islamic/Arab name) or Satan, but Yazidis find that offensive and do not actually mention that name.[29]

Seven Angels[]

The Seven Angels are the emanations of God, which are said to have been created by God from his own light (Nûr). In this context they have, so to speak, a part of God in themselves. Another word that is used for this is Sur or Sirr (literally: 'mystery'), which denotes a divine essence that the angels were created from.[30] This pure divine essence called Sur or Sirr has its own personality and will and is also called Sura Xudê ('the Sur of God').[31] This term refers to the essence of the Divine itself, that is, God. The Angels share this essence from their creator who is God. The Seven Angels are sometimes referred to as "the Seven Mysteries" (heft sirr).[30] In Yazidi literature, these Angels are referred to as Cibrayîl, Ezrayîl, Mîkayîl, Şifqayîl, Derdayîl, Ezafîl, and Ezazîl.[32] The most important of these Angels is known as Tawûsê Melek, and the others are better known by the names of their humanly incarnations/representations: Fexreddin, Shex Shems, Nasirdin, Sijadin, Şêxobekir, and Shex Hesen (Şêxsin).[33][34][35]

Sheikh ‘Adī[]

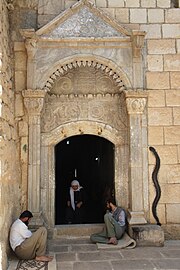

One of the important figures of Yazidism is Sheikh 'Adī ibn Musafir. Sheikh 'Adī ibn Musafir settled in the valley of Laliş (some 58 kilometres (36 mi) northeast of Mosul) in the Yazidi mountains in the early 12th century and founded the 'Adawiyya Sufi order. He died in 1162, and his tomb at Laliş is a focal point of Yazidi pilgrimage and the principal Yazidi holy site.[36] Yazidism has many influences: Sufi influence and imagery can be seen in the religious vocabulary, especially in the terminology of the Yazidis' esoteric literature, but most of the theology, rituals, traditions, and festivals remains non-Islamic. Its cosmogony for instance has many points in common with those of ancient Iranian religions.[8][9][10][11][12]

Rebirth and concept of time[]

Yezidis believe in the rebirth of the soul. Like the Ahl-e Haqq, the Yazidis use the metaphor of a change of garment to describe the process, which plays an exceptional role in Yezidi religiosity and is called the "change of [one’s] shirt" (Kurdish: kirasgorîn). There is also a belief that some of the events from the time of creation repeat themselves in cycles of history. In Yezidism, different concepts of time coexist:[6]

- An esoteric time sphere (Kurdish: enzel), This term denotes a state of being before the creation of the world. According to Yezidi cosmogony, there is God and a pearl in this stage.

- Bedîl or Dewr (a cyclic course of time): it means literally 'change, changing' or 'turning, revolution' and in the Yezidi context denotes a new period of time in the history of the world. Therefore, it may also mean 'renewing' or 'renewed' and designates the start of a renewed period of time.

- A linear course, which runs from the start of the creation by God to the collective eschatological end point.

- Three tofans ('storm, flood') i.e. catastrophes. It is believed that there are three big events during history named tofan that play a purificatory role, changing the quality of life in a positive manner. Each catastrophe, which ultimately brings renewal to the world, takes place through a basic element: the first through water (tofanê avê), the second through fire (tofanê agirî) and the last is connected with wind (air) (tofanê ba). It is believed that the first tofan has already occurred in the past and that the next tofan will occur through fire. According to this perception, the three sacred elements, namely water, fire and air, purify the fourth one, the earth. These events however are not be considered as eschatological events. They occur during the life of people. Although the purificatory events cause many deaths, ultimately life continues.[37]

In Yezidism, the older original concept of metempsychosis and the cyclic perception of the course of time is harmonised and coexists with the younger idea of a collective eschatology.[6]

Cosmogony and beginning of life[]

The Yezidi cosmogony is recorded in several sacred texts and traditions. It can therefore only be inferred and understood through an overall view of the sacred texts and traditions. The cosmogony can be divided into three stages:

- Enzel – the state before the Big Bang, i.e. before the pearl burst (Kurdish Dur).

- Developments immediately after the Big Bang – cosmogony II

- The creation of the earth and man – anthropogony[38][39]

The term Enzel is one of the frequently mentioned terms in the religious vocabulary and it comes up numerous times in the religious hymns, known as Qewls. For instance, in Qewlê Tawisî Melek:

"Ya Rebî ji Enzel de her tuyî qedîmî" (English: Oh, Creator of the Enzel, you are infinite)[40]

And Dûa Razanê:

Ezdayî me, ji direke enzelî me (English: I am a follower of God, I come from an "enzelî" pearl)[40]

Thus, the term Enzel can also be referred to as a "pure, spiritual, immaterial and infinite world", "the Beyond" or "the sphere beyond the profane world". The Enzel stage describes a spaceless and timeless state and therefore illustrates a supernatural state. In this stage, initially there is only a God, who creates a pearl out of his own light, in which his shining throne (Textê nûrî) is located.

Qewlê Bê Elif:

Padşê min bi xo efirandî dura beyzaye – My King created the white pearl from himself

Textê nûrî sedef – The shining throne in the pearl[40]

Once the pearl burst open, the beginning of the material universe was set in motion. Mihbet (meaning 'love') came into being and was laid as the original foundation, colours began to form, and red, yellow and white began to shine from the burst pearl.

The Yezidi religion has its own perception of the colours, which is seen in the mythology and shown through clothing taboos, in religious ceremonies, customs and rituals. Colours are perceived as the symbolizations of nature and the beginning of life, thus the emphasis of colours can be found in the creation myth. The colors white, red, green and yellow in particular are frequently emphasized. White is considered the color of purity and peace and is the main colour of the religious clothing of the Yezidis.[41][12][39]

Yazidi accounts of the creation differ significantly from those of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), since they are derived from the Ancient Mesopotamian and Indo-Iranian traditions; therefore, Yazidi cosmogony is closer to those of Ancient Iranian religions, Yarsanism, and Zoroastrianism.[42][43]

Yazidi sacred texts[]

The religious literature of Yezidis is composed mostly of poetry which is orally transmitted in mainly Kurmanji and includes numerous genres, such as Qewl (religious hymn), Beyt (poem), Du‛a (prayer), Dirozge (another kind of prayer), Şehdetiya Dîn (the Declaration of the Faith), Terqîn (prayer for after a sacrifice), Pişt Perde (literally 'under the veil', another genre), Qesîde (Qasida), Sema‛ (literally 'listening'), Lavij, Xerîbo, Xizêmok, Payîzok, and Robarîn. The poetic literature is composed in an advanced and archaic language where more complex terms are used, which may be difficult to understand for those who are not trained in religious knowledge.[citation needed] Therefore, they are accompanied by some prosaic genres of the Yezidi literature that often interpret the contents of the poems and provide explanations of their contexts in the spoken language comprehensible among the common population. The prosaic genres include Çîrok and Çîvanok (legends and myths), and Dastan and M‛ena/Pirs (interpretations of religious hymns).[44][45] Yezidis also possess some written texts, such as the sacred manuscripts called mişȗrs and individual collections of religious texts called Cilvê and Keşkûl, although they are rarer and often safekept among Yezidis.[46] Yezidis are also said to have two holy books, Kitêba Cilwe (Book of Revelation) and Mishefa Reş (Black Book) whose authenticities are debated among scholars[45]

Holy books[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Yazidi holy books are claimed to be the Kitêba Cilwe (Book of Revelation) and the Mishefa Reş (Black Book). Scholars generally agree that the manuscripts of both books published in 1911 and 1913 were forgeries written by non-Yazidis in response to Western travellers' and scholars' interest in the Yazidi religion; however, the material in them is consistent with authentic Yazidi traditions.[45] True texts of those names may have existed, but remain obscure. The real core texts of the religion that exist today are the hymns known as qawls; they have also been orally transmitted during most of their history, but are now being collected with the assent of the community, effectively transforming Yazidism into a scriptural religion.[45] The sacred texts had already been translated into English by the early 20th century.[47]

Qewl and Beyt[]

A very important genre of oral literature of the Yezidi community consists of religious hymns, called Qewls, which literally means 'word, speech' (from Arabic qawl). The performers of these hymns, called the Qewwal, constitute a distinct class within the Yezidi society. They are a veritable source of ancient Yezidi lore and are traditionally recruited from the non-religious members of other Kurdish tribes, principally the Dimli and Hekkaris.[48][15][6] The qewls are full of cryptic allusions and usually need to be accompanied by čirōks ('stories') that explain their context.[45]

Mishur[]

Mishurs are a type of sacred manuscripts that were written down in the 13th century and handed down to each lineage (Ocax) of the Pirs; each of the manuscripts contain descriptions of the founder of the Pir lineage that they were distributed to, along with a list of Kurdish tribes and other priestly lineages that were affiliated with the founder. The mishurs are safekept among the families of Pirs in particular places that are designated for their safekeeping; these places are referred to as stêr in Kurmanji.[49] According to the Yezidi tradition, there are a total of 40 mishurs which were distributed to the 40 lineages of Pirs.[6]

Festivals[]

Yazidi New Year[]

The Yazidi New Year (Sersal) is called Çarşema Sor ("Red Wednesday")[20] or Çarşema Serê Nîsanê ("Wednesday at the beginning of April")[50] and it falls in spring, on the first Wednesday of the April and Nîsan months in the Julian and Seleucid calendars, i.e. the first Wednesday on or after 14 April according to the Gregorian calendar.[51][13] The celebrations start on the eve of Wednesday, i.e. Tuesday evening (Yezidis believe 24 hours of the day start at sunset), eggs are boiled and coloured, the festive sawuk bread is baked, the graves are visited to commemorate the dead and bring offerings and fruits for them. Yezidis also wear festive garments and visit nearby temples, in particular Lalish, where the sacred Zemzem spring, which runs in a dark cave, is located. Yezidis offer sacrifices on the entrance at the entrance to the cave and receive blessings. The hills surrounding Lalish are climbed, where they fasten colourful ribbons to the wishing trees. Red flowers are collected from the wilderness which some attach to their hair or turban and later use to decorate their houses with, oils are burnt and bonfires are lit at night. The people exchange gifts with close friends or neighbours.[12][52]

The festive game hekkane is also played by all Yezidis, which involves egg tapping; the cracking of the egg is supposed to represent the bursting of the primordial White Pearl (i.e. the Big Bang) and beginning of life.[20] A great cleaning is carried out on the temples and animals are sacrificed. In the evening, pilgrims gather in the inner courtyard of Lalish where the Baba Sheikh and other religious dignitaries are present. They wait until sunset for the priest bearing the sacred fire to emerge from the temple, from this fire, they all light the specially prepared wicks placed on mostly small stones, oil lamps and pans.[53] The Baba Sheikh turns toward the temple's entrance and recites religious hymns together with other priests who are present. As it gets darker, the pilgrims relocate to the outer yard in front of the temple where the Qawwals, surrounded by the halo of a thousand of tiny flames and accompanied by the Moonlight, recite religious hymns with accompaniment of flutes and tambours. The crowds later surround the priests and dignitaries to shout the sacred names, in particular that of Tawûsê Melek, before departing home.

Before daybreak, a mixture of clay, broken shells of the coloured eggs, red flowers and curry softened with water is applied beside the doors or entrances of houses and sacred places. This is accompanied by reciting the Qewlê Çarşemê hymn.

The rest of the day is spent visiting neighbours, giving and receiving gifts, feasting and playing hekkane. Travelling is refrained from because this day is believed to be the most unlucky day of the year; this belief is also linked with Chaharshanbe Suri by Iranians.[54][page needed] In Lalish, a basin with the water from the Zemzem spring is prepared and the head clergy, including Baba Sheikh, Baba Chawish, and the Peshimam, gather in the inner courtyard where the Sheikhan Sancak is brought in, unveiled and dismantled to be ritually washed with the sacred water by each of the clerics. The sancak is thus ready to be paraded around in the vicinity for the Tawûsgeran festival.

The festival is considered to be a representation of the cosmogony, thus the celebrations, rituals and activities that are conducted during the festival, correspond to the cosmogonical stages. For example, the cleaning represents the state of indefiniteness, the visiting to the graves represents the Enzel stage, i.e. the state of immateriality. The egg represents the primordial White Pearl, thus, when the egg is cracked, it represents the bursting of the White Pearl, beginning of life and emergence of colors. The lit fires represent dispersion of light, the visit to Zemzem spring represents gushing of the infinite waters and the mixture of clay, water, eggshells and flowers represents the amalgamation of the elements which led to the creation of the material world. Lastly, the washing of the Sancak represents descent of Tawûsê Melek to earth.[52]

"Hat çarşema sorê,

Nîsan xemilandibû bi xorê,

Ji batin da ye bi morê.

Hat çarşema sor û zerê,

Bihar xemilandibû ji kesk û sor û sipî û zerê,

Me pê xemilandin serederê."(English: "The Red Wednesday has come,

Nîsan is adorned with the sun,

Blessed with concealment.

The Red and Yellow Wednesday has come,

The spring is adorned with green, red, white and yellow,

And we have decorated our door lintels with them")

Feast of Êzî[]

One of the most important Yazidi festivals is Îda Êzî ("Feast of Êzî"). Which every year takes place on the first Friday on or after the 14th of December. Before this festival, the Yazidis fast for three days, where nothing is eaten from sunrise to sunset. The Îda Êzî festival is celebrated in honor of God and the three days of fasting before are also associated with the ever shorter days before the winter solstice, when the sun is less and less visible. With the Îda Êzî festival, the fasting time is ended. The festival is often celebrated with music, food, drinks and dance.[56]

Tawûsgeran[]

Another important festival is the Tawûsgeran where Qewals and other religious dignitaries visit Yazidi villages, bringing the sinjaq, sacred images of a peacock symbolizing Tawûsê Melek. These are venerated, fees are collected from the pious, sermons are preached and holy water and berat (small stones from Lalish) distributed.[57][58]

Feast of the Assembly[]

The greatest festival of the year is the Cêjna Cemaiya ('Feast of the Assembly'), which includes an annual pilgrimage to the tomb of Sheikh 'Adī' (Şêx Adî) in Lalish, northern Iraq. The festival is celebrated from 6 October to 13 October,[59] in honor of the Sheikh Adi. It is an important time for cohesion.[60]

If possible, Yazidis make at least one pilgrimage to Lalish during their lifetime, and those living in the region try to attend at least once a year for the Feast of the Assembly in autumn.[61]

During the festival, the whole community comes together, all tribal chiefs, religious dignitaries and authorities are together in one place and special performances, celebrations and rituals are performed, this includes processions, communal meals, theatrical performances, recitals of qewls, animal sacrifices and candle lighting, this festival is also celebrated joyously with dances, musical performances, markets, and games. It offers a great opportunity for young Yezidis to meet, date, and party.

During the first few days of the pilgrimage, thousands of pilgrims arrive at the Bridge of Silat, which symbolizes the crossing from the profane life into the sacred life. Everyone is required to remove their shoes, wash their hands in the river, and cross the bridge three times while carrying torches and singing hymns. Thereafter, they walk to Sheikh 'Adī's tomb. They circumambulate three times around the building before kissing the doorframe and entering. They take their places around a five-branched torch and watch the first evening dance. The evening dance, called Sema Êvarî, is performed on every evening of the festival. During the dance, twelve men, dressed in white, circumambulate around a sacred torch lit in the middle which represents both God and the sun. The twelve men sing hymns as they pace slowly and solemnly. They are accompanied by the music of three Qawwals, who are trained singers and reciters of religious hymns. Pilgrims also visit the sacred white stone located on top of the Arafat mountain next to the sanctuary, which is one of the three mountains next in the Lalish valley surrounding the temple. They walk around the white stone seven times, kiss it to show reverence and offer a sum of money to the guardian of the site.

On the fourth day of the festival, the garments that cover and decorate Sheikh 'Adī's tomb are washed in the holy water of the Zemzem spring, located in a dark cave. Religious hymns are sung as they are dried and hung back in place. The seven differently colored garments, which represent the seven Holy Beings reigning over the earth, are each to be separately taken off and ritually washed.

On the fifth day, a bull is sacrificed in front of the shrine of Sheikh Shems, who is one of the seven Holy Beings in Yezidism who personifies the sun. Three tribes, namely Qaidy, Tirk, and Mamusi, are tasked with bringing a bull to the centre of Lalish, and chasing it down to the shrine of Sheikh Shems, where it is to be caught and ceremonially killed. The meat is later cooked and distributed to the pilgrims at Lalish.

The last two days of the festival consist of a ceremonial sheep sacrifice by the locals of Ain Sifni, and bringing the funeral bier of Sheikh 'Adī', which is located in Baadre, to Lalish, where it is baptized, i.e. ritually washed, with water from the sacred spring. Religious hymns are recited as pilgrims begin to depart.[62][63][34][15][64]

This festival corresponds to the ancient Iranian feast of Mehragan, which also typically involved animal sacrifice. The ceremonial bull sacrifice in particular has been shown to be similar with the ancient Iranian tradition, as the bull sacrifice takes place in front of Sheikh Shems, a solar being that shares a lot of similar traits with the Ancient Iranian solar deity Mithra, who is repeatedly depicted slaying a bull and who also had a festival, during the same season, celebrated in his honour.[65][66][page needed][10][67]

Tiwaf[]

Tiwafs are yearly feasts of shrines and their holy beings which constitute an important part of Yezidi religious and communal life. Every village that contains a shrine holds annual tiwafs in the name of the holy being to which the shrine is dedicated. Tiwafs are accompanied by numerous rituals which vary from shrine to shrine. These rituals may include performances of the qewwals with their musical instruments, changing and renewing of the coloured strips of cloth (perî) that hang from the spire of the shrine, ritual meals either for the heads of the households or for the whole village, or cooked parts of the sacrificial sheep being auctioned off to bidders among the cheering crowd. The tiwafs in other places also include trips into nature to reach a sacred spot, lending an air of picnic to the occasion, one example is during the tiwaf at the shrine of Kerecal near Sharya, which takes place on a mountain, or at the sacred place of Sexrê Cinê located deep inside the Valley of Jinn near Bozan. In many places, large and communal dances are also included in the tiwafs. Tiwafs are not necessarily attended solely by the locals of the village itself, the participants may also include many of the other Yezidis, particularly the ones who have relatives in the village or have a special attachment with the holy being to which the shrine is dedicated. Together with keeping the Yezidi religious customs alive, tiwafs also serve to strengthen the social ties between families and the communal solidarity, both on the village and inter-village levels.[68][69]

Religious practices[]

Prayers[]

Prayers occupy a special status in Yezidi literature. They contain important symbols and religious knowledge connected with the Holy Men, God, and daily situations. The prayers are mostly private and as a rule they are not performed in public. Yezidis pray towards the sun,[63] usually privately, or the prayers are recited by one person during a gathering. The prayers are classified according to their own content. There are:

- Prayers dedicated to God and holy beings,

- Prayers of Yezidi castes,

- Prayers for specific occasions,

- Rites de passage prayers,

- Prayers against health problems and illnesses,

- Daily prayers,

- Prayers connected with the nature, i.e. the moon, stars, sun, etc.[44]

Purity and taboos[]

Many Yazidis consider pork to be prohibited. However, many Yazidis living in Germany began to view this taboo as a foreign belief from Judaism or Islam and not part of Yazidism, and therefore abandoned this rule.[71] Furthermore, in a BBC interview in April 2010, Baba Sheikh, the spiritual leader of all Yezidis, stated that ordinary Yazidis may eat what they want, but the religious clergy refrain from certain vegetables (including cabbage) because "they cause gases".[72]

Some Yazidis in Armenia and Georgia who converted to Christianity, still identify as Yazidis even after converting,[73] but are not accepted by the other Yazidis as Yazidis.[74]

Customs[]

Children are baptised at birth and circumcision is not required, but is practised by some due to regional customs.[75] The Yazidi baptism is called Mor kirin (literally: 'to seal'). Traditionally, Yazidi children are baptised at birth with water from the Kaniya Sipî ('White Spring') at Lalish.[76]

Religious organisation[]

The Yazidis are strictly endogamous;[77][78] members of the three Yazidi castes, the murids, sheikhs, and pirs, marry only within their group.[25]

There are several religious duties and that are performed by several dignitaries.

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yazidism. |

References[]

- ^ "Yezidis divided on spiritual leader's successor elect rival Mir".

- ^ "The Yazidis are still struggling to survive". The Economist. 2020-12-10. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014). "Part I: The One God - Malak-Tāwūs: The Leader of the Triad". The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Gnostica. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 1–28. doi:10.4324/9781315728896. ISBN 978-1-84465-761-2. OCLC 931029996.

- ^ Rodziewicz, Artur (2018). "Chapter 7: The Nation of the Sur: The Yezidi Identity Between Modern and Ancient Myth". In Bocheńska, Joanna (ed.). Rediscovering Kurdistan's Cultures and Identities: The Call of the Cricket. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 272. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93088-6_7. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- ^ "مهزارگههێ شهرفهدین هێشتا ژ ئالیێ هێزێن پێشمهرگهی ڤه دهێته پاراستن" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Omarkhali, Khanna (2017). The Yezidi religious textual tradition, from oral to written : categories, transmission, scripturalisation, and canonisation of the Yezidi oral religious texts : with samples of oral and written religious texts and with audio and video samples on CD-ROM. ISBN 978-3-447-10856-0. OCLC 994778968.

- ^ "Social Change Amidst Terror and Discrimination: Yezidis in the New Iraq". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Turgut, Lokman. Ancient rites and old religions in Kurdistan. OCLC 879288867.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kaczorowski, Karol (2014). "Yezidism and Proto-Indo-Iranian Religion". Fritillaria Kurdica. Bulletin of Kurdish Studies (3–4).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Foltz, Richard (2017-06-01). "The "Original" Kurdish Religion? Kurdish Nationalism and the False Conflation of the Yezidi and Zoroastrian Traditions". Journal of Persianate Studies. 10 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1163/18747167-12341309. ISSN 1874-7094.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Omarkhali, Khanna (2009–2010). "The status and role of the Yezidi legends and myths: to the question of comparative analysis of Yezidism, Yārisān (Ahl-e Haqq) and Zoroastrianism: a common substratum?". Folia Orientalia. 45–46: 197–219. OCLC 999248462.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (1995). Yezidism--its Background, Observances, and Textual Tradition. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-9004-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bozarslan, Hamit; Gunes, Cengiz; Yadirgi, Veli, eds. (2021-04-22). The Cambridge History of the Kurds (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108623711. ISBN 978-1-108-62371-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Allison, Christine (25 January 2017). "The Yazidis". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.254. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (January 2003). Asatrian, Garnik S. (ed.). "Malak-Tāwūs: The Peacock Angel of the Yezidis". Iran and the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill Publishers in collaboration with the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies (Yerevan). 7 (1–2): 1–36. doi:10.1163/157338403X00015. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 4030968. LCCN 2001227055. OCLC 233145721.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (December 2009). "Names of God and Forms of Address to God in Yezidism. With the Religious Hymn of the Lord". Manuscripta Orientalia International Journal for Oriental Manuscript Research. 15 (2).

- ^ Kartal, Celalettin (2016-06-22). Deutsche Yeziden: Geschichte, Gegenwart, Prognosen (in German). Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 9783828864887.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rodziewicz, Artur (December 2016). Asatrian, Garnik S. (ed.). "And the Pearl Became an Egg: The Yezidi Red Wednesday and Its Cosmogonic Background". Iran and the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill Publishers in collaboration with the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies (Yerevan). 20 (3–4): 347–367. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20160306. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 44631092. LCCN 2001227055. OCLC 233145721.

- ^ Izady, Mehrdad (2015). The Kurds: A Concise History And Fact Book. ISBN 9781135844905. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014-09-03). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54428-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khalaf, Farida; Hoffmann, Andrea C. (2016-07-07). The Girl Who Escaped ISIS: Farida's Story. Random House. ISBN 9781473524163.

- ^ Jump up to: a b van Bruinessen, Martin (1992). "Chapter 2: Kurdish society, ethnicity, nationalism and refugee problems". In Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (eds.). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 26–52. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6. OCLC 919303390.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London: I.B. Tauris & Company. ISBN 978-1-784-53216-1. OCLC 888467694.

- ^ Li, Shirley (8 August 2014). "A Very Brief History of the Yazidi and What They're Up Against in Iraq". The Atlantic.

- ^ Jalabi, Raya (11 August 2014). "Who are the Yazidis and why is Isis hunting them?". The Guardian.

- ^ Thomas, Sean (19 August 2007). "The Devil worshippers of Iraq". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Evolution of the Yezidi Religion. From Spoken Word to Written Scripture" (PDF). The Evolution of Yezidi Religion - From Spoken Word to Written Scripture. Openaccess.leidenuniv.nl. 1. ISIM, Leiden. 1998. p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spät, Eszter (2009). "Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition" (PDF). Central European University. p. 71.

- ^ Rodziewicz, Artur (2018). "Chapter 7: The Nation of the Sur: The Yezidi Identity Between Modern and Ancient Myth". In Bocheńska, Joanna (ed.). Rediscovering Kurdistan's Cultures and Identities: The Call of the Cricket. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93088-6_7. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- ^ Авдоев, Теймураз (2011). Историко-теософский аспект езидизма [Historical and Theosophical Aspect of Yezidism] (in Russian). p. 314. ISBN 978-5-905016-967.

- ^ Murad, Jasim Elias (1993). The Sacred Poems of the Yazidis: An Anthropological Approach. University of California, Los Angeles.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (1995). Yezidism--its Background, Observances, and Textual Tradition. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-9004-8.

- ^ Açikyildiz, Birgül (2019-12-17). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-350-14927-4.

- ^ Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition by Eszter Spät. Ch. 9 "The Origin Myth of the Yezidis" section "The Myth of Shehid Bin Jer" (p. 347)

- ^ Agustí., Allison, Christine, ed. Joisten-Pruschke, Anke, ed. Wendtland, Antje, ed. Kreyenbroek, Philip G., 1948- Alemany i Vilamajó (2009). From Daena to Din : religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt : festschrift für Philip Kreyenbroek zum 60. Geburtstag. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05917-6. OCLC 1120653126.

- ^ Franz, Erhard (2004). "Yeziden - Eine alte Religionsgemeinschaft zwischen Tradition und Moderne" (PDF). Deutsches Orient-Institut.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Omarkhali, Khanna; Rezania, K. (2009). "Some reflections on the concepts of time in Yezidism". In Christine Allison; Anke Joisten-Pruschke; Antje Wendtland (eds.). From Daēnā to Dîn Religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Авдоев, Теймураз (2020). NEWŞE DÎNÊ ÊZÎDIYAN ЕЗИДСКОЕ СВЯЩЕНОСЛОВИЕ THE YEZIDI HOLY HYMNES.

- ^ "Schöpfungsmythos – Êzîpedia" (in German). Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ Richard Foltz Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present Oneworld Publications, 01.11.2013 ISBN 9781780743097 p. 221

- ^ Omarkhali, Khanna (2009–2010). "The status and role of the Yezidi legends and myths. To the question of comparative analysis of Yezidism, Yārisān (Ahl-e Haqq) and Zoroastrianism: a common substratum?". Folia Orientalia. 45–46.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Omarkhali, Khanna (2011-03-20). "YEZIDI RELIGIOUS ORAL POETIC LITERATURE: STATUS, FORMAL CHARACTERISTICS, AND GENRE ANALYSIS: With some examples of Yezidi religious texts". Scrinium. 7–8 (2): 144–195. doi:10.1163/18177565-90000247. ISSN 1817-7530.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Encyclopaedia Iranica: Yazidis". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ Bocheńska, Joanna, ed. (2018). Rediscovering Kurdistan's Cultures and Identities. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93088-6. ISBN 978-3-319-93087-9.

- ^ "Devil worship"; the sacred books and traditions of the Yezidiz

- ^ Cheung, Johnny. "Qewl | Yezidi Stories". Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Pirbari, Dimitri; Mossaki, Nodar; Yezdin, Mirza Sileman (2019-11-19). "A Yezidi Manuscript:—Mišūr of P'īr Sīnī Bahrī/P'īr Sīnī Dārānī, Its Study and Critical Analysis". Iranian Studies. 53 (1–2): 223–257. doi:10.1080/00210862.2019.1669118. ISSN 0021-0862. S2CID 214483496.

- ^ Авдоев, Теймураз (2017-09-05). Историко-теософский аспект езидизма (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 9785040433988.

- ^ "Das êzîdîsche Neujahr" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rodziewicz, Artur (2016-12-19). "And the Pearl Became an Egg: The Yezidi Red Wednesday and Its Cosmogonic Background". Iran and the Caucasus. 20 (3–4): 347–367. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20160306. ISSN 1609-8498.

- ^ Murad, Jasim Elias (1993). The sacred poems of the Yazidis: an anthropological approach (PhD thesis). UCLA. OCLC 31142482.

- ^ Mokri, Mohammad (1963). Les rites magiques dans les fêtes du "Dernier Mercredi de l'Année" en Iran (in French). [s.n.] OCLC 1020478355.

- ^ Issa, Chaukeddin; Maisel, Sebastian; Tolan, Telim (2008). Das Yezidentum: Religion und Leben (in German). Oldenburg: Dengê Êzîdiyan. ISBN 978-3-9810751-4-4. OCLC 716937172.

- ^ Urban, Elke (2019-07-24). Transkulturelle Pflege am Lebensende: Umgang mit Sterbenden und Verstorbenen unterschiedlicher Religionen und Kulturen (in German). Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 9783170359383.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2009). Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak about Their Religion. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447060608.

- ^ Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- ^ Guest (2012-11-12). Survival Among The Kurds. Routledge. ISBN 9781136157363.

- ^ Yousefi, Hamid Reza; Seubert, Harald (2014-07-22). Ethik im Weltkontext: Geschichten - Erscheinungsformen - Neuere Konzepte (in German). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783658048976.

- ^ Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- ^ Staff (2017-04-25). "The Yezidi Holidays - Sacred Days, Pilgrimages - Mystery Religions in Iraq". Servant Group International. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- ^ Spät, Eszter. "THE FESTIVAL OF SHEIK ADI IN LALISH, THE HOLY VALLEY OF THE YEZIDIS". unknown journal.

- ^ "Philip KREYENBROEK World Congress of KURDISH STUDIES". Institutkurde.org. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Foltz, Richard C. (7 November 2013). Religions of Iran : from prehistory to the present. ISBN 978-1-78074-307-3. OCLC 839388544.

- ^ Spat, Eszter; Spät, Eszter (2005). The Yezidis. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-593-9.

- ^ Spat, Eszter (2016-10-08). "Hola Hola Tawusi Melek, Hola Hola Şehidêt Şingalê: Persecution and the Development of Yezidi Ritual Life". Kurdish Studies. 4 (2): 155–175. doi:10.33182/ks.v4i2.426. ISSN 2051-4891.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (1995). Yezidism--its Background, Observances, and Textual Tradition. E. Mellen Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7734-9004-8.

- ^ Lair, Patrick (19 January 2008). "Conversation with a Yazidi Kurd". eKurd Daily. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Halil Savucu: Yeziden in Deutschland: Eine Religionsgemeinschaft zwischen Tradition, Integration und Assimilation Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-828-86547-1, Section 16 (German)

- ^ "Richness of Iraq's minority religions revealed", BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Population (urban, rural) by Ethnicity, Sex and Religious Belief" (PDF). Statistics of Armenia. Statistics of Armenia. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Aghayeva, Elene Shengelia, Rana (2018-09-06). "Georgia's Yazidis: Religion as Identity - Religious Beliefs". chai-khana.org. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ Parry, O. H. (Oswald Hutton) (1895). "Six months in a Syrian monastery; being the record of a visit to the head quarters of the Syrian church in Mesopotamia, with some account of the Yazidis or devil worshippers of Mosul and El Jilwah, their sacred book". London : H. Cox.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2009). Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak about Their Religion. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06060-8.

- ^ Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- ^ Gidda, Mirren. "Everything You Need to Know About the Yazidis". TIME.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

Bibliography[]

- Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014). "Part I: The One God - Malak-Tāwūs: The Leader of the Triad". The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Gnostica. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 1–28. doi:10.4324/9781315728896. ISBN 978-1-84465-761-2. OCLC 931029996.

- Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (January 2003). Asatrian, Garnik S. (ed.). "Malak-Tāwūs: The Peacock Angel of the Yezidis". Iran and the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill Publishers in collaboration with the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies (Yerevan). 7 (1–2): 1–36. doi:10.1163/157338403X00015. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 4030968. LCCN 2001227055. OCLC 233145721.

- Rodziewicz, Artur (December 2016). Asatrian, Garnik S. (ed.). "And the Pearl Became an Egg: The Yezidi Red Wednesday and Its Cosmogonic Background". Iran and the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill Publishers in collaboration with the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies (Yerevan). 20 (3–4): 347–367. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20160306. eISSN 1573-384X. ISSN 1609-8498. JSTOR 44631092. LCCN 2001227055. OCLC 233145721.

- Sfameni Gasparro, Giulia (April 1975). Feldt, Laura; Valk, Ülo (eds.). "I Miti Cosmogonici degli Yezidi". Numen (in Italian). Leiden: Brill Publishers. 22 (1): 24–41. doi:10.1163/156852775X00112. eISSN 1568-5276. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269532. LCCN 58046229. OCLC 50557232.

- Sfameni Gasparro, Giulia (December 1974). Feldt, Laura; Valk, Ülo (eds.). "I Miti Cosmogonici degli Yezidi". Numen (in Italian). Leiden: Brill Publishers. 21 (3): 197–227. doi:10.1163/156852774X00113. eISSN 1568-5276. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269773. LCCN 58046229. OCLC 50557232.

- Asian ethnic religion

- Iranian religions

- Mesopotamian religion

- Monotheistic religions

- Religion in Armenia

- Religion in Georgia (country)

- Religion in Iraq

- Religion in Kurdistan

- Religion in Syria

- Religion in Turkey

- Yazidi culture

- Yazidi mythology