Jet Propulsion Laboratory

| |

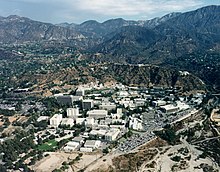

Aerial view of JPL | |

| Established | October 31, 1936 |

|---|---|

| Research type | Applied |

| Director | Michael M. Watkins |

| Staff | > 6,000 |

| Address | 4800 Oak Grove Drive |

| Location | Pasadena, California, United States 34°12′6.1″N 118°10′18″W / 34.201694°N 118.17167°WCoordinates: 34°12′6.1″N 118°10′18″W / 34.201694°N 118.17167°W |

Subdivision | JPL Science Division |

Operating agency | Managed for NASA by Caltech |

| Website | www |

| Map | |

Location in California | |

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the city of Pasadena in California, United States.

Founded in the 1930s, JPL is owned by NASA and managed by the nearby California Institute of Technology (Caltech).[1] The laboratory's primary function is the construction and operation of planetary robotic spacecraft, though it also conducts Earth-orbit and astronomy missions. It is also responsible for operating the NASA Deep Space Network.

Among the laboratory's major active projects are the Mars 2020 mission, which includes the Perseverance rover and the Ingenuity Mars helicopter; the Mars Science Laboratory mission, including the Curiosity rover; the InSight lander (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport); the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter; the Juno spacecraft orbiting Jupiter; the SMAP satellite for earth surface soil moisture monitoring; the NuSTAR X-ray telescope; and the forthcoming Psyche asteroid orbiter. It is also responsible for managing the JPL Small-Body Database, and provides physical data and lists of publications for all known small Solar System bodies.

JPL's Space Flight Operations Facility and Twenty-Five-Foot Space Simulator are designated National Historic Landmarks.

History[]

JPL traces its beginnings to 1936 in the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT) when the first set of rocket experiments were carried out in the Arroyo Seco.[2] Caltech graduate students Frank Malina, Qian Xuesen, [3] and Apollo M. O. Smith, along with Jack Parsons and , tested a small, alcohol-fueled motor to gather data for Malina's graduate thesis.[citation needed] Malina's thesis advisor was engineer/aerodynamicist Theodore von Kármán, who eventually arranged for U.S. Army financial support for this "GALCIT Rocket Project" in 1939. In 1941, Malina, Parsons, Forman, Martin Summerfield, and pilot Homer Bushey demonstrated the first jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) rockets to the Army. In 1943, von Kármán, Malina, Parsons, and Forman established the Aerojet Corporation to manufacture JATO rockets. The project took on the name Jet Propulsion Laboratory in November 1943, formally becoming an Army facility operated under contract by the university.[4][5][6][7] In 1944, Parsons was expelled due to his "unorthodox and unsafe working methods" following one of several FBI investigations into his involvement with the occult, drugs and sexual promiscuity. [8][9]

During JPL's Army years, the laboratory developed two deployed weapon systems, the MGM-5 Corporal and MGM-29 Sergeant intermediate-range ballistic missiles. These missiles were the first US ballistic missiles developed at JPL.[10] It also developed a number of other weapons system prototypes, such as the Loki anti-aircraft missile system, and the forerunner of the Aerobee sounding rocket. At various times, it carried out rocket testing at the White Sands Proving Ground, Edwards Air Force Base, and Goldstone, California.[7]

In 1954, JPL teamed up with Wernher von Braun's engineers at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, to propose orbiting a satellite during the International Geophysical Year. The team lost that proposal to Project Vanguard, and instead embarked on a classified project to demonstrate ablative re-entry technology using a Jupiter-C rocket. They carried out three successful sub-orbital flights in 1956 and 1957. Using a spare Juno I (a modified Jupiter-C with a fourth stage), the two organizations then launched the United States' first satellite, Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958.[5][6]

JPL was transferred to NASA in December 1958,[11] becoming the agency's primary planetary spacecraft center. JPL engineers designed and operated Ranger and Surveyor missions to the Moon that prepared the way for Apollo. JPL also led the way in interplanetary exploration with the Mariner missions to Venus, Mars, and Mercury.[5] In 1998, JPL opened the for NASA.[12] As of 2013, it has found 95% of asteroids that are a kilometer or more in diameter that cross Earth's orbit.[13]

JPL was early to employ female mathematicians. In the 1940s and 1950s, using mechanical calculators, women in an all-female computations group performed trajectory calculations.[14][15] In 1961, JPL hired Dana Ulery as the first female engineer to work alongside male engineers as part of the Ranger and Mariner mission tracking teams.[16]

JPL has been recognized four times by the Space Foundation: with the Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award, which is given annually to an individual or organization that has made significant contributions to public awareness of space programs, in 1998; and with the John L. "Jack" Swigert, Jr., Award for Space Exploration on three occasions – in 2009 (as part of NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander Team[17]), 2006 and 2005.

Location[]

When it was founded, JPL's site was immediately west of a rocky flood-plain – the Arroyo Seco riverbed – above the Devil's Gate dam in the northwestern panhandle of the city of Pasadena in Southern California, near Los Angeles. While the first few buildings were constructed in land bought from the city of Pasadena,[18] subsequent buildings were constructed in neighboring unincorporated land that later became part of La Cañada Flintridge. Nowadays, most of the 177 acres (72 ha) of the U.S. federal government-owned NASA property that makes up the JPL campus is located in La Cañada Flintridge.[19][20] Despite this, JPL still uses a Pasadena address (4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109) as its official mailing address.[21] There has been occasional rivalry between the two cities over the issue of which one should be mentioned in the media as the home of the laboratory.[20][22][23][24]

Employees[]

There are approximately 6,000 full-time Caltech employees, and typically a few thousand additional contractors working on any given day. NASA also has a resident office at the facility staffed by federal managers who oversee JPL's activities and work for NASA. There are also some Caltech graduate students, college student interns and co-op students.

Education[]

The JPL Education Office serves educators and students by providing them with activities, resources, materials and opportunities tied to NASA missions and science. The mission of its programs is to introduce and further students' interest in pursuing STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers.[25]

Internships and fellowships[]

JPL offers research, internship and fellowship opportunities in the summer and throughout the year to high school through postdoctoral and faculty students. (In most cases, students must be U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents to apply, although foreign nationals studying at U.S. universities are eligible for limited programs.) Interns are sponsored through NASA programs, university partnerships and JPL mentors for research opportunities at the laboratory in areas including technology, robotics, planetary science, aerospace engineering, and astrophysics.[26]

In August 2013, JPL was named one of "The 10 Most Awesome College Labs of 2013" by Popular Science, which noted that about 100 students who intern at the laboratory are considered for permanent jobs at JPL after they graduate.[27]

The JPL Education Office also hosts the Planetary Science Summer School (PSSS), an annual week-long workshop for graduate and postdoctoral students. The program involves a one-week team design exercise developing an early mission concept study, working with JPL's Advanced Projects Design Team ("Team X") and other concurrent engineering teams.[28]

Museum Alliance[]

JPL created the NASA Museum Alliance in 2003 out of a desire to provide museums, planetariums, visitor centers and other kinds of informal educators with exhibit materials, professional development and information related to the then-upcoming landings of the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity.[29] The Alliance now has more than 500 members, who get access to NASA displays, models, educational workshops and networking opportunities through the program. Staff at educational organizations that meet the Museum Alliance requirements can register to participate online.[30]

The Museum Alliance is a subset of the JPL Education Office's Informal Education group, which also serves after-school and summer programs, parents and other kinds of informal educators.[31]

Educator Resource Center[]

The NASA/JPL Educator Resource Center, which is moving from its location at the Indian Hill Mall in Pomona, Calif. at the end of 2013,[32] offers resources, materials and free workshops for formal and informal educators covering science, technology, engineering and science topics related to NASA missions and science.

Open house[]

The lab had an open house once a year on a Saturday and Sunday in May or June, when the public was invited to tour the facilities and see live demonstrations of JPL science and technology. More limited private tours are also available throughout the year if scheduled well in advance. Thousands of schoolchildren from Southern California and elsewhere visit the lab every year.[33] Due to federal spending cuts mandated by budget sequestration, the open house has been previously cancelled.[34] JPL open house for 2014 was October 11 and 12 and 2015 was October 10 and 11. Starting from 2016, JPL replaced the annual Open House with "Ticket to Explore JPL", which features the same exhibits but requires tickets and advance reservation.[35] Roboticist and Mars rover driver Vandi Verma frequently acts as science communicator at open house type events to encourage children (and particularly girls) into STEM careers.[36][37][38]

Other works[]

In addition to its government work, JPL has also assisted the nearby motion picture and television industries, by advising them about scientific accuracy in their productions. Science fiction shows advised by JPL include Babylon 5 and its sequel series, Crusade.

JPL also works with the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (DHSSTD). JPL and DHSSTD developed a search and rescue tool for first responders called FINDER. First responders can use FINDER to locate people still alive who are buried in rubble after a disaster or terrorist attack. FINDER uses microwave radar to detect breathing and pulses.[39]

Additionally, JPL is home to the JPL-RPIF (Jet Propulsion Laboratory - Regional Planetary Image Facility) which is chartered as a repository for all robotic spacecraft hard-copy data and thus provides a valuable resource to NASA funded science investigators, and an important conduit for the distribution of NASA generated materials to local educators in the Los Angeles/southern California area.[40][41]

Funding[]

JPL is a federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) managed and operated by Caltech under a contract from NASA. In fiscal year 2012, the laboratory's budget was slightly under $1.5 billion, with the largest share going to Earth Science and Technology development.

Peanuts tradition[]

There is a tradition at JPL to eat "good luck peanuts" before critical mission events, such as orbital insertions or landings. As the story goes, after the Ranger program had experienced failure after failure during the 1960s, the first successful Ranger mission to impact the Moon occurred after a JPL staff member had decided to pass out peanuts to relieve tension. The staff jokingly decided that the peanuts must have been a good luck charm, and the tradition persisted.[42][43]

Missions[]

These are some of the missions partially sponsored by JPL:[44]

- ASTERIA (spacecraft)

- Cassini–Huygens

- CloudSat

- Deep Space 1 and 2

- Europa Clipper

- Explorer program

- Galileo probe

- Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE)

- Juno

- Magellan probe

- Mariner program

- Mars 2020

- Mars Climate Orbiter

- Mars Cube One

- Mars Exploration Rover Mission

- Mars Global Surveyor

- Mars Odyssey

- Mars Pathfinder

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Mars Science Laboratory

- Ocean Surface Topography Mission (OSTM/Jason-2)

- Orbiting Carbon Observatory

- Phoenix spacecraft

- Pioneer 3 and 4

- Psyche: Journey to a Metal World

- Ranger program

- Shuttle Radar Topography Mission

- Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP)

- Spitzer Space Telescope

- Stardust

- Surveyor program

- Viking program

- Voyager program (Voyager 1 and Voyager 2)

- Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2

- Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer

List of directors[]

- Theodore von Kármán, 1938 – 1944

- Frank Malina, 1944 – 1946

- Louis Dunn, 1946 – October 1, 1954

- William Hayward Pickering, October 1, 1954 – March 31, 1976

- Bruce C. Murray, April 1, 1976 – June 30, 1982

- Lew Allen, Jr., July 22, 1982 – December 31, 1990

- Edward C. Stone, January 1, 1991 – April 30, 2001

- Charles Elachi, May 1, 2001 – June 30, 2016[45]

- Michael M. Watkins, July 1, 2016[46] – present

Team X[]

The JPL Advanced Projects Design Team, also known as Team X, is an interdisciplinary team of engineers that utilizes "concurrent engineering methodologies to complete rapid design, analysis and evaluation of mission concept designs".[47]

Controversies[]

Employee background check lawsuit[]

On February 25, 2005, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 was approved by the Secretary of Commerce.[48] This was followed by Federal Information Processing Standards 201 (FIPS 201), which specified how the federal government should implement personal identity verification. These specifications led to a need for rebadging to meet the updated requirements.

On August 30, 2007, a group of JPL employees filed suit in federal court against NASA, Caltech, and the Department of Commerce, claiming their constitutional rights were being violated by the new, overly invasive background investigations.[49] 97% of JPL employees were classified at the low-risk level and would be subjected to the same clearance procedures as those obtaining moderate/high risk clearance. Under HSPD 12 and FIPS 201, investigators have the right to obtain any information on employees, which includes questioning acquaintances on the status of the employee's mental, emotional, and financial stability. Additionally, if employees depart JPL before the end of the two-year validity of the background check, no investigation ability is terminated; former employees can still be legally monitored.

Employees were told that if they did not sign an unlimited waiver of privacy,[50] they would be deemed to have "voluntarily resigned".[51] The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found the process violated the employees' privacy rights and issued a preliminary injunction.[52] NASA appealed and the US Supreme Court granted certiorari on March 8, 2010. On January 19, 2011, the Supreme Court overturned the Ninth Circuit decision, ruling that the background checks did not violate any constitutional privacy right that the employees may have had.[53]

Coppedge v Jet Propulsion Laboratory[]

On March 12, 2012, the Los Angeles Superior Court took opening statements on the case in which former JPL employee David Coppedge brought suit against the lab due to workplace discrimination and wrongful termination. In the suit, Coppedge alleges that he first lost his "team lead" status on JPL's Cassini-Huygens mission in 2009 and then was fired in 2011 because of his evangelical Christian beliefs and specifically his belief in intelligent design. Conversely, JPL, through the Caltech lawyers representing the laboratory, allege that Coppedge's termination was simply due to budget cuts and his demotion from team lead was because of harassment complaints and from on-going conflicts with his co-workers.[54] Superior Court Judge Ernest Hiroshige issued a final ruling in favor of JPL on January 16, 2013.[55]

References[]

- ^ "History". www.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ Zibit, Benjamin Seth (1999). The Guggenheim Aeronautics Laboratory at Caltech and the creation of the modern rocket motor (1936-1946): How the dynamics of rocket theory became reality (Thesis). Bibcode:1999PhDT........48Z.

- ^ Smith, Richard Harris. "The 'Mystery Man' of Cal Tech's Jet Propulsion Laboratory".

- ^ "Early Years". JPL.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Koppes, Clayton (1 April 1982). "JPL and the American Space Program". The American Historical Review. New Haven: Yale University Press. 89 (2).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conway, Erik M. "From Rockets to Spacecraft: Making JPL a Place for Planetary Science". Engineering and Science. pp. 2–10. Archived from the original on 2011-01-07. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Launius, Roger (2002). To Reach High Frontier, A History of U.S. Launch Vehicles. University of Kentucky. pp. 39–42. ISBN 978-0-813-12245-8.

- ^ Solon, Olivia (April 23, 2014). "Occultist father of rocketry 'written out' of Nasa's history". Wired UK. Condé Nast. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Oleksinski, Johnny (June 19, 2018). "This sex-crazed cultist was the father of modern rocketry". New York Post. News Corp. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Keymeulen, Didier; Myers, John; Newton, Jason; Csaszar, Ambrus; et al. (2006). Humanoids for Lunar and Planetary Surface Operations. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Pasadena, CA: JPL TRS 1992+. hdl:2014/39699.

- ^ Bello, Francis (1959). "The Early Space Age". Fortune. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ Whalen, Mark; Murrill, Mary Beth (24 July 1998). "JPL will establish Near-Earth Object Program Office for NASA". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "NASA scrambles for better asteroid detection". France 24. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Women Made Early Inroads at JPL - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ [1] Archived November 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bibliography" (PDF). pub-lib.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Henry, Jason (13 June 2016). "Why does everyone say NASA's JPL is in Pasadena when this other city is its real home?". Pasadena Star-News.

- ^ "Local Agency Formation Commission for the County of Los Angeles" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Location of NASA's JPL is a bit of a curiosity". 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Directions and Maps". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Pasadena to ask JPL land annexation", Pasadena Star News 11, March 1976;

- ^ "JPL Faces an identity crisis following incorporation vote", Pasadena Star News, 15 Nov 1976

- ^ "The great battle for JPL," La Canada Valley Sun 18 Mar. 1976

- ^ Jpl.Nasa.Gov. "About Us - JPL Education - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Jpl.Nasa.Gov. "Student Programs, Internships & Fellowships at JPL - JPL Education - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "The 10 Most Awesome College Labs Of 2013 | Popular Science". Popsci.com. 2013-08-20. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Planetary Science Summer School". Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Jpl.Nasa.Gov (2012-05-23). "JPL Education - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "About Us | Museum Alliance". Informal.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Jpl.Nasa.Gov. "Inspire - JPL Education - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Jpl.Nasa.Gov. "Educator Resource Center - JPL Education - NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "JPL Open House". Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "Open House At JPL Closed To Public Over Sequestration " CBS Los Angeles". Losangeles.cbslocal.com. 2013-04-22. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Ticket to Explore JPL Public Events

- ^ "Vandi Tompkins talk to the Mars Lab". Mars Lab TV (on YouTube). Event occurs at 19'45. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Siders, Jennifer Torres. "Women from JPL, which is managed for NASA by Caltech, address high school students. Prospective Applicants Explore Opportunities for Women at Caltech". Caltech. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Life on Mars". Twig Education. 2017-06-06. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Bryan. "DHS staff members attend annual Day on the Hill" Archived 2014-02-16 at archive.today. BioPrepWatch. February 10, 2014 (Retrieved 02-10-2014).

- ^ "OVERVIEW OF THE REGIONAL PLANETARY IMAGE FACILITY (RPIF) AT THE JET PROPULSION LABORATORY" (PDF). 47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 2016.

- ^ "RPIF". rpif.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2019-03-16.

- ^ "NPR All Things Considered interview referring to peanuts tradition". Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "Planetary Society chat log for Phoenix referring to peanuts tradition". Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ JPL. "NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory: Missions". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "JPL Directors". JPL. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "News | Michael Watkins Named Next JPL Director". May 2, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "JPL Team X". Jplteamx.jpl.nasa.gov. August 31, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ HSPD-12 and JPL Rebadging Overview. HSPD12 JPL. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ Overview. HSPD12 JPL. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ US Office of Personnel Management. "Questionnaire for Non-Sensitive Positions" (PDF). Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Declaration of Cozette Hart, JPL Human Resources Director" (PDF). October 1, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Nelson v. NASA -- Preliminary Injunction issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit" (PDF). Jan 11, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ National Aeronautics and Space Administration et al. v. Nelson et al., No. 09-530 (U.S. January 19, 2011).

- ^ "Former NASA specialist claims he was fired over intelligent design". Fox News. March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Judge confirms earlier ruling, sides with JPL in 'intelligent design' case". La Canada Valley Sun. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

Further reading[]

- Conway, Erik M. Exploration and Engineering: The Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Quest for Mars (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016) 405 pp.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jet Propulsion Laboratory. |

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Space technology research institutes

- Federally Funded Research and Development Centers

- Laboratories in California

- Research institutes in California

- University and college laboratories in the United States

- La Cañada Flintridge, California

- NASA facilities

- NASA visitor centers

- Buildings and structures in Los Angeles County, California

- Buildings and structures in Pasadena, California

- Government agencies established in 1930

- Think tanks established in 1930

- 1930 establishments in California

- 20th century in Los Angeles

- 21st century in Los Angeles

- Science and technology in Greater Los Angeles

- JPL online services